Nonviolent Action and Transitions to Democracy the IMPACT of INCLUSIVE DIALOGUE and NEGOTIATION by Véronique Dudouet and Jonathan Pinckney

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Dialogue and Economic Performance What Matters for Business - a Review

Social Dialogue and Economic Performance What matters for business - A review Damian Grimshaw Aristea Koukiadaki Isabel Tavora CONDITIONS OF WORK AND EMPLOYMENT SERIES No. 89 INWORK Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 89 Social Dialogue and Economic Performance: What Matters for Business - A review Damian Grimshaw Aristea Koukiadaki Isabel Tavora Work and Equalities Institute, University of Manchester, UK INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFFICE - GENEVA Copyright © International Labour Organization 2017 First published 2017 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. ISSN: 2226-8944 ; 2226-8952 (web pdf). The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them. -

Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements

BETWEEN MAO AND GANDHI: STRATEGIES OF VIOLENCE AND NONVIOLENCE IN REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENTS A thesis Presented to the Faculty of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy by CHES THURBER In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2015 Dissertation Committee: Richard Shultz, Chair H. Zeynep Bulutgil Erica Chenoweth CHES THURBER 104 E. Main St. #2, Gloucester, MA 02155 [email protected] | (617) 710-2617 DOB: September 21, 1982 in New York, NY, USA EDUCATION Tufts University, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy PH.D. | International Relations (2015) Dissertation: “Between Mao and Gandhi: Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements” Committee: Richard Shultz, Zeynep Bulutgil, Erica Chenoweth M.A.L.D. | International Relations (2010) Middlebury College B.A. | International Studies (summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, 2004) ACADEMIC University of Chicago APPOINTMENTS Postdoctoral Fellow, Chicago Project on Security and Terrorism (Beginning Aug. 1, 2015) Program on Political Violence Harvard University Research Fellow, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs (2014-2015) International Security Program PUBLICATIONS “Militias as Sociopolitical Movements: Lessons from Iraq’s Armed Shia Groups" in Small Wars and Insurgencies 25, nos. 5-6 (October 2014): 900-923. Review of The Maoist Insurgency in Nepal: Revolution in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Mahendra Lawoti and Anuk K. Pahari, in Himalaya 34, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 148-150. “A Step Short of the Bomb: Explaining the Strategy of Nuclear Hedging” in Journal of Public and International Affairs (2011). “From Coexistence to Cleansing: The Rise of Sectarian Violence in Baghdad, 2003-2006” in al-Nakhlah: Journal of Southwest Asia and Islamic Civilization (March 2011). -

Lessons for Emergent Post-Modern Democrats by Ken White

Extreme Democracy 90 8 The dead hand of modern democracy: Lessons for emergent post-modern democrats By Ken White et us not be too hasty to bury the present; it’s not dead yet, and a pre- mortem might provide some useful information. Those of us moving L ahead ought to remember Santayana’s famous dictum, and meditate— deeply—on what, and whom, we might leave behind. Emergent democracy can augment and, perhaps, even gradually supplant outmoded forms of self-governance, but only if we appreciate why those forms were once “moded”—suited to their times and uses. After all, Democracy 2.0 (if we consider Athens “1.0”) has enjoyed a pretty good 220- year run, even with all its failings. Considering which critical functions of modern democracy deserve preservation in intent, if not in form, offers the opportunity to appreciate the rich complexity of democratic self-governance and its astonishingly diverse modes of participation and action. By attending to what made modern democracy successful we might learn a few lessons; extract some insights from the old model; and identify a few pitfalls we ought to avoid, even as we cheerfully acknowledge the inevitability of creating a new set of pitfalls. I draw on personal experience in arriving at this conclusion. Working in the United States on democratic reforms (including campaign financing) for many years, I came to appreciate the difference between “reform” and “redesign.” Although the former may occur more often in some limited way, the promise of the latter drives truly significant change. As Extreme Democracy 91 Buckminster Fuller said: “You never change things by fighting against the existing reality. -

South Korea: Legal and Political Overtones of Defensive Democracy in a Divided Country South Korea Has Already Passed Samuel

South Korea: Legal and Political Overtones of Defensive Democracy in a Divided Country KWANGSUP KIM South Korea has already passed Samuel Huntington’s two-turnover test for democratic consolidation, which occurred with the peaceful transitions of power in 1992 and 1996. This occurred despite the enduring military tension on the divided Korean peninsula. Huntington said that when a nation transitions from an “emergent democracy” to a “stable democracy,” its ruling parties must undergo two democratic and peaceful turnovers.1 However, there still exists heated controversy over whether the executive power violates democratic rule and human rights in the name of national security. This is despite the fact that the military authoritarian regime perished in 1987 and subsequent civilian governments have accomplished democratic reform. On November 6, 2013, the Ministry of Justice in South Korea petitioned to the Constitutional Court to rule on dissolving the minor Unified Progressive Party (UPP) for violating the “basic rules of democracy.”2 The ministry’s filing comes after the prosecution of indicted lawmaker, Lee Seok-ki of the UPP on September 5, 2013, on charges of conspiracy to stage a rebellion, incitement and sympathizing with North Korea, and infringement of the Kwangsup Kim is a Ph.D. Fellow at Center for Constitutional Democracy of Indiana University Maurer School of Law, an academic director and vice chairperson of the Committee of Women’s Rights at the Human Rights & Welfare Institution of Korea., and a Member of the Board of Directors at The Correction Welfare Society of Korea. 1 Samuel P. Huntington, “The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century.” Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 14 (1991): 26. -

Civil Resistance Against Coups a Comparative and Historical Perspective Dr

ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES Civil Resistance Against Coups A Comparative and Historical Perspective Dr. Stephen Zunes ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES Cover Photos: (l) Flickr user Yamil Gonzales (CC BY-SA 2.0) June 2009, Tegucigalpa, Honduras. People protesting in front of the Presidential SERIES EDITOR: Maciej Bartkowski Palace during the 2009 coup. (r) Wikimedia Commons. August 1991, CONTACT: [email protected] Moscow, former Soviet Union. Demonstrators gather at White House during the 1991 coup. VOLUME EDITOR: Amber French DESIGNED BY: David Reinbold CONTACT: [email protected] Peer Review: This ICNC monograph underwent four blind peer reviews, three of which recommended it for publication. After Other volumes in this series: satisfactory revisions ICNC released it for publication. Scholarly experts in the field of civil resistance and related disciplines, as well as People Power Movements and International Human practitioners of nonviolent action, serve as independent reviewers Rights, by Elizabeth A. Wilson (2017) of ICNC monograph manuscripts. Making of Breaking Nonviolent Discipline in Civil Resistance Movements, by Jonathan Pinckney (2016) The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle, by Tenzin Dorjee (2015) Publication Disclaimer: The designations used and material The Power of Staying Put, by Juan Masullo (2015) presentedin this publication do not indicate the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of ICNC. The author holds responsibility for the selection and presentation of facts contained in Published by ICNC Press this work, as well as for any and all opinions expressed therein, which International Center on Nonviolent Conflict are not necessarily those of ICNC and do not commit the organization 1775 Pennsylvania Ave. NW. Ste. -

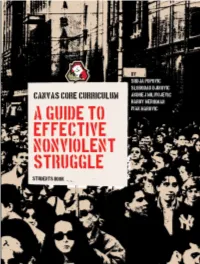

Canvas Core Curriculum: a Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle

CANVAS CORE CURRICULUM: A GUIDE TO EFFECTIVE NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE STUDENTS BOOK by CANVAS printed and published in Serbia 2007 CANVAS Curriculum Introduction Before you is a wealth of knowledge about the planning, conduct, and Srdja Popovic, Slobodan Djinovic, Andrej Milivojevic, Hardy Merriman evaluation of strategic nonviolent conflict. This curriculum guide will be a and Ivan Marovic valuable companion to new and experienced activists, as well as to others who wish to learn about this subject. CANVAS Core Curriculum: A Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle Copyright 2007 by CANVAS. All rights reserved. The authors combine classic insights about nonviolent conflict with new ideas based on recent experience. The result is a synthesis that pushes the Published in Serbia, 2007. limits of what we thought nonviolent strategies were capable of achieving. The material covered includes time-tested analyses of power, different ISBN 978-86-7596-087-4 methods of nonviolent action, and ways to create a strategic plan for developing and mobilizing a movement. In addition, the authors include new material about how to: Publisher: Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS) • chart a movement’s history and progress (Chapter 8) Masarikova 5/ XIII, Belgrade, Serbia, www.canvasopedia.org • use marketing, branding, and effective communication techniques in a movement (Chapters 9 and 10) Graphic design and illustrations: Ana Djordjevic • address the effects of fear on a movement’s members (Chapter 13) • develop security measures within a movement (Chapter 14) Photo on cover: Igor Jeremic • manage a movement’s material resources, human resources, and time (Advanced Chapters 2-4) Throughout these topics, the authors emphasize pragmatic learning and draw on their own experience applying these ideas in their own struggles. -

SAKHAROV PRIZE NETWORK NEWSLETTER 10/2015 Raif Badawi Is the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought's Newest Laureate 29/10/2015

SAKHAROV PRIZE NETWORK NEWSLETTER 10/2015 Raif Badawi is the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought's newest laureate 29/10/2015 the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought for 2015 has been awarded to Saudi blogger Raif Badawi. EP President Schulz called Badawi ‘a hero in our modern internet world who is fighting for democracy and facing real torture’ as he announced the decision taken by the Conference of Presidents. ‘I have asked the King of Saudi Arabia to pardon Badawi and release him to give him the chance to receive the Sakharov Prize here in the European Parliament’, the EP President and Sakharov Prize Network co-chair said. Badawi was shortlisted as a finalist for the Prize together with the Democratic Opposition in Venezuela and murdered Russian opposition politician and activist Boris Nemtsov by a vote of the Foreign Affairs and Development Committees. The initial list of nominees included also Edna Adan Ismail, Nadiya Savchenko, and Edward Snowden, Antoine Deltour and Stéphanie Gibaud. Link: President Schulz press point Flogging of Raif Badawi to resume, wife warns 27/10/2015: Ensaf Haidair, the wife of Saudi blogger, 2015 SP laureate, Raif Badawi, said she has been informed that the Saudi authorities have given the green light to the resumption of her husband's flogging. In a statement published on the Raif Badawi Foundation website, Haidar said that she received her information from the same source who had warned her about Badawi’s pending flogging at the beginning of January 2015, a few days before Badawi was flogged. Link: Fondation Raif Badawi Xanana Gusmao and DEVE Delegation at Milan EXPO on Feeding the Planet 15/10/2015: 1999 Sakharov Prize laureate and first President of Timor-Leste, Xanana Gusmão, and a delegation of the EP’s DEVE Committee led by Chairwoman and SPN Member Linda McAvan tackled the right to food, land rights and the use of research for the effective realisation of the Sustainable Development Goals during an intensive two day-programme in Milan. -

The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: a Strategic and Historical Analysis

ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: A Strategic and Historical Analysis Tenzin Dorjee ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES Cover photos: (l) John Ackerly, 1987, (r) Invisible Tibet Blog SERIES EDITOR: Maciej Bartkowski John Ackerly’s photo of the first major demonstration in Lhasa in 1987 CONTACT: [email protected] became an emblem for the Tibet movement. The monk Jampa Tenzin, who is being lifted by fellow protesters, had just rushed into a burning VOLUME EDITORS: Hardy Merriman, Amber French, police station to rescue Tibetan detainees. With his arms charred by the Cassandra Balfour flames, he falls in and out of consciousness even as he leads the crowd CONTACT: [email protected] in chanting pro-independence slogans. The photographer John Ackerly Other volumes in this series: became a Tibet advocate and eventually President of the International Campaign for Tibet (1999 to 2009). To read more about John Ackerly’s The Power of Staying Put: Nonviolent Resistance experience in Tibet, see his book co-authored by Blake Kerr, Sky Burial: against Armed Groups in Colombia, Juan Masullo An Eyewitness Account of China’s Brutal Crackdown in Tibet. (2015) Invisible Tibet Blog’s photo was taken during the 2008 Tibetan uprising, The Maldives Democracy Experience (2008-13): when Tibetans across the three historical provinces of Tibet rose up From Authoritarianism to Democracy and Back, to protest Chinese rule. The protests began on March 10, 2008, a few Velezinee Aishath (2015) months ahead of the Beijing Olympic Games, and quickly became the largest, most sustained nonviolent movement Tibet has witnessed. Published by the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict The designations used and material presented in this publication do P.O. -

Against the Death Penalty What Is It? Goals

WORLD CONGRESS AGAINST THE DEATH PENALTY 26TH FEBRUARY - 1ST MARCH 2019 - BRUSSELS - BELGIUM Organised by In partnership with Sponsored by Held under the patronage of Co-funded by the European Union congres.ecpm.org #7CongressECPM WORLD CONGRESS AGAINST THE DEATH PENALTY WHAT IS IT? GOALS Encourage the involvement in the international anti-death penalty movement: private Date: 26 February to 1 March 2019 sector, sports, etc. Location: Brussels (Belgium) Put in place a global strategy to move the last retentionist countries towards abolition. Duration: 4 days Accompany Africa towards abolition: could Africa be the next abolitionist continent? Number of participants: 1,500 per day Counter populist movements, make progress in raising awareness about abolition and make Reach of the event: an average of 115 countries represented at previous congresses younger generations actors of change. Break the isolation of civil society, which works on a daily basis to abolish the death penalty The 7th World Congress in Brussels has been preceded by the 3rd Regional Congress Against the death in retentionist or moratorium countries by promoting networking. Death Penalty which took place on 9 and 10 April 2018 in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. Raise awareness among the Belgian population and teach young people, from Belgium and beyond, about abolition of the death penalty. Organiser: ECPM (Together against the death penalty) www.ecpm.org BENEFICIARIES Abolitionist civil society, coalitions of actors against the death penalty and their member Sponsored by organisations working for fundamental rights. Held under Co-funded by The 150 members of the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty. the patronage of the European Union National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs). -

YUGOSLAV REFUGEES, DISPLACED PERSONS and the CIVIL WAR Mirjana Morokvasic Freie Universitm, Berlin and Centre Nationale De La Recherche Scientifique, Paris

YUGOSLAV REFUGEES, DISPLACED PERSONS AND THE CIVIL WAR Mirjana Morokvasic Freie UniversitM, Berlin and Centre Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris Background case among the socialist countries. The within the boundaries of former Slovenia and Croatia declared present tragedy can only be compared Yugoslavia, the Yugoslav case may also independence on 25 June 1991. That to that of the Second World War; from help de-dramatize the East I West was the date of the "collective an international perspective, the invasion scenarios which predict thanatos"' which led to the United Nations High Commission on disruptive mass movements caused by disintegration of Yugoslavia. As a Refugees (UNHCR) compares it in political and ethnic violence or result of German pressure, the scope, scale of atrocities and ecological catastrophe in the countries European Community, followed by a consequences for the population, to the aligned with the former Soviet empire. number of other states, recognized the Cambodian civil war. The Demographic Structure In three ways, analyzing the independence of the secessionist The 600,000 to 1 million displaced refugees' situation contributes to our republics on 15 January 1992 and persons referred to above come from understanding of issues beyond the buried the second Y~goslavia.~ Croatia, whose total population is 4.7 human tragedy of the people Although the Westernmedia have million (see Figure 1).Moreover, most themselves. First, it demystifies the now shifted their attention to the of these people come from a relatively genesis of the Yugoslav conflict, which former Soviet Union, where other small area the front line, which is now is often reduced to a matter "ethnic - similar and potentially even more under the control of the Yugoslav hatred." It shows that the separation of dangerous ethnic conflicts are brewing, Army and Serbian forces. -

Tunisian Democracy Group Wins Nobel Peace Prize 9 October 2015, Bymark Lewis and Karl Ritter

Tunisian democracy group wins Nobel Peace Prize 9 October 2015, byMark Lewis And Karl Ritter Tunisian protesters sparked uprisings across the Arab world in 2011 that overthrew dictators and upset the status quo. Tunisia is the only country in the region to painstakingly build a democracy, involving a range of political and social forces in dialogue to create a constitution, legislature and democratic institutions. "More than anything, the prize is intended as an encouragement to the Tunisian people, who despite major challenges have laid the groundwork for a national fraternity which the committee hopes will serve as an example to be followed by other countries," committee chair Kaci Kullmann Five said. Kaci Kullmann Five, the new head of the Norwegian Nobel Peace Prize Committee, announces the winner of The National Dialogue Quartet is made up of four 2015 Nobel peace prize during a press conference in key organizations in Tunisian civil society: the Oslo, Norway, Friday Oct. 9, 2015. The Norwegian Tunisian General Labour Union; the Tunisian Nobel Committee announced Friday that the 2015 Nobel Confederation of Industry, Trade and Handicrafts; Peace Prize was awarded to the Tunisian National the Tunisian Human Rights League; and the Dialogue Quartet. (Heiko Junge/NTB scanpix via AP) Tunisian Order of Lawyers. Kullmann Five said the prize was for the quartet as a whole, not the four individual organizations. A Tunisian democracy group won the Nobel Peace Prize on Friday for its contributions to the first and The decision came as a surprise to many, with most successful Arab Spring movement. speculation having focused on Europe's migrant crisis or the Iran-U.S. -

World Development Studies 9 the Elusive Miracle

UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNUAVIDER) World Development Studies 9 The elusive miracle Latin America in the 1990s Hernando Gomez Buendia This study has been prepared within the UNUAVIDER project on the Challenges of Globalization, Regionalization and Fragmentation under the 1994-95 research programme. Professor Hernando Gomez Buendia was holder of the UNU/WIDER-Sasakawa Chair in Development Policy in 1994-95. UNUAVIDER gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Sasakawa Foundation. UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU/WIDER) A research and training centre of the United Nations University The Board of UNU/WIDER Sylvia Ostry Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo, Chairperson Antti Tanskanen George Vassiliou Ruben Yevstigneyev Masaru Yoshitomi Ex Officio Heitor Gurgulino de Souza, Rector of UNU Giovanni Andrea Cornia, Director of UNU/WIDER UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU/WIDER) was established by the United Nations University as its first research and training centre and started work in Helsinki, Finland in 1985. The purpose of the Institute is to undertake applied research and policy analysis on structural changes affecting the developing and transitional economies, to provide a forum for the advocacy of policies leading to robust, equitable and environmentally sustainable growth, and to promote capacity strengthening and training in the field of economic and social policy making. Its work is carried out by staff researchers and visiting scholars in Helsinki and through networks of collaborating scholars and institutions around the world. UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU/WIDER) Katajanokanlaituri 6 B 00160 Helsinki, Finland Copyright © UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU/WIDER) Cover illustration prepared by Juha-Pekka Virtanen at Forssa Printing House Ltd Camera-ready typescript prepared by Liisa Roponen at UNU/WIDER Printed at Forssa Printing House Ltd, 1996 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s).