The Struggle for National Identity in Nonviolent Revolutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coalitions in Ukraine's Orange Revolution

psr1300029 xxx (xxx) June 17, 2013 20:48 American Political Science Review Vol. 107, No. 3 August 2013 doi:10.1017/S0003055413000294 c American Political Science Association 2013 The Semblance of Democratic Revolution: Coalitions in Ukraine’s Orange Revolution MARK R. BEISSINGER Princeton University sing two unusual surveys, this study analyzes participation in the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine, comparing participants with revolution supporters, opponents, counter-revolutionaries, U and the apathetic/inactive. As the analysis shows, most revolutionaries were weakly committed to the revolution’s democratic master narrative, and the revolution’s spectacular mobilizational success was largely due to its mobilization of cultural cleavages and symbolic capital to construct a negative coalition across diverse policy groupings. A contrast is drawn between urban civic revolutions like the Orange Revolution and protracted peasant revolutions. The strategies associated with these revolution- ary models affect the roles of revolutionary organization and selective incentives and the character of revolutionary coalitions. As the comparison suggests, postrevolutionary instability may be built into urban civic revolutions due to their reliance on a rapidly convened negative coalition of hundreds of thousands, distinguished by fractured elites, lack of consensus over fundamental policy issues, and weak commitment to democratic ends. t is widely acknowledged that the character of political freedoms in their immediate wake, though in revolution has -

Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements

BETWEEN MAO AND GANDHI: STRATEGIES OF VIOLENCE AND NONVIOLENCE IN REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENTS A thesis Presented to the Faculty of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy by CHES THURBER In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2015 Dissertation Committee: Richard Shultz, Chair H. Zeynep Bulutgil Erica Chenoweth CHES THURBER 104 E. Main St. #2, Gloucester, MA 02155 [email protected] | (617) 710-2617 DOB: September 21, 1982 in New York, NY, USA EDUCATION Tufts University, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy PH.D. | International Relations (2015) Dissertation: “Between Mao and Gandhi: Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements” Committee: Richard Shultz, Zeynep Bulutgil, Erica Chenoweth M.A.L.D. | International Relations (2010) Middlebury College B.A. | International Studies (summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, 2004) ACADEMIC University of Chicago APPOINTMENTS Postdoctoral Fellow, Chicago Project on Security and Terrorism (Beginning Aug. 1, 2015) Program on Political Violence Harvard University Research Fellow, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs (2014-2015) International Security Program PUBLICATIONS “Militias as Sociopolitical Movements: Lessons from Iraq’s Armed Shia Groups" in Small Wars and Insurgencies 25, nos. 5-6 (October 2014): 900-923. Review of The Maoist Insurgency in Nepal: Revolution in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Mahendra Lawoti and Anuk K. Pahari, in Himalaya 34, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 148-150. “A Step Short of the Bomb: Explaining the Strategy of Nuclear Hedging” in Journal of Public and International Affairs (2011). “From Coexistence to Cleansing: The Rise of Sectarian Violence in Baghdad, 2003-2006” in al-Nakhlah: Journal of Southwest Asia and Islamic Civilization (March 2011). -

People Power: the Everyday Politics of Democratic Resistance in Burma and the Philippines

People Power: The Everyday Politics of Democratic Resistance in Burma and the Philippines Nicholas Henry A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Relations Victoria University of Wellington 2011 ii ... the tale he had to tell could not be one of a final victory. It could be only the record of what had had to be done, and what assuredly would have to be done again in the never ending fight against terror and its relentless onslaughts, despite their personal afflictions, by all who, while unable to be saints but refusing to bow down to pestilences, strive their utmost to be healers. Albert Camus, The Plague This thesis is dedicated to all those who, resisting the terror of state violence, continue to do what has to be done. iii Abstract How do Community Based Organisations (CBOs) in Burma and the Philippines participate in the construction of political legitimacy through their engagement in local and international politics? What can this tell us about the agency of non-state actors in international relations? This thesis explores the practices of non-state actors engaged in political resistance in Burma and the Philippines. The everyday dynamics of political legitimacy are examined in relation to popular consent, political violence, and the influence of international actors and norms. The empirical research in this thesis is based on a grounded theory analysis of in-depth semi-structured interviews with a wide cross-section of spokespeople and activists of opposition groups from Burma, and with spokespeople of opposition groups in the Philippines. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E559 HON

April 2, 1998 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E559 Members of the Congressional Hispanic Cau- TRIBUTE TO DR. AND MRS. country in welcoming His Excellency, Fidel cus (CHC). During their meeting with the CHARLES AND REBECCA GUNNOE Valdez Ramos, the President of the Republic CHC, we had the opportunity to discuss the of the Philippines, to the United States as he political and economic integration process of HON. KEN CALVERT visits our nation's capital next week. MERCOSUR and the effects of this free-trade OF CALIFORNIA As with the island of Guam, the rest of the pact on the United States economy. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES United States have for over a century shared historic, cultural, political and economic ties Data from the Department of Commerce on Wednesday, April 1, 1998 the current balance of trade between with the Republic of the Philippines. President MERCOSUR and the United States shows Mr. CALVERT. Mr. Speaker, throughout this Ramos is the embodiment of these ties. He that the United States not only enjoys a sur- country of ours there are a few individuals comes from very respected and prominent plus in trade with MERCOSUR, but also re- who, because they contribute so generously of families in the Philippines. His Father Narciso veals that exports to MERCOSUR countries their time and talents to help others, are rec- Ramos was a lawyer, crusading journalist, and are significantly larger than those to China and ognized as pillars of their community. Charles five-term member of the Philippine House of Russia together, $23.3 billion versus $16 bil- and Rebecca Gunnoe are two individuals who Representatives, who was later appointed lion. -

Civil Resistance Against Coups a Comparative and Historical Perspective Dr

ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES Civil Resistance Against Coups A Comparative and Historical Perspective Dr. Stephen Zunes ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES Cover Photos: (l) Flickr user Yamil Gonzales (CC BY-SA 2.0) June 2009, Tegucigalpa, Honduras. People protesting in front of the Presidential SERIES EDITOR: Maciej Bartkowski Palace during the 2009 coup. (r) Wikimedia Commons. August 1991, CONTACT: [email protected] Moscow, former Soviet Union. Demonstrators gather at White House during the 1991 coup. VOLUME EDITOR: Amber French DESIGNED BY: David Reinbold CONTACT: [email protected] Peer Review: This ICNC monograph underwent four blind peer reviews, three of which recommended it for publication. After Other volumes in this series: satisfactory revisions ICNC released it for publication. Scholarly experts in the field of civil resistance and related disciplines, as well as People Power Movements and International Human practitioners of nonviolent action, serve as independent reviewers Rights, by Elizabeth A. Wilson (2017) of ICNC monograph manuscripts. Making of Breaking Nonviolent Discipline in Civil Resistance Movements, by Jonathan Pinckney (2016) The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle, by Tenzin Dorjee (2015) Publication Disclaimer: The designations used and material The Power of Staying Put, by Juan Masullo (2015) presentedin this publication do not indicate the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of ICNC. The author holds responsibility for the selection and presentation of facts contained in Published by ICNC Press this work, as well as for any and all opinions expressed therein, which International Center on Nonviolent Conflict are not necessarily those of ICNC and do not commit the organization 1775 Pennsylvania Ave. NW. Ste. -

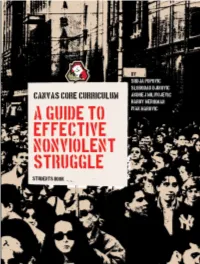

Canvas Core Curriculum: a Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle

CANVAS CORE CURRICULUM: A GUIDE TO EFFECTIVE NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE STUDENTS BOOK by CANVAS printed and published in Serbia 2007 CANVAS Curriculum Introduction Before you is a wealth of knowledge about the planning, conduct, and Srdja Popovic, Slobodan Djinovic, Andrej Milivojevic, Hardy Merriman evaluation of strategic nonviolent conflict. This curriculum guide will be a and Ivan Marovic valuable companion to new and experienced activists, as well as to others who wish to learn about this subject. CANVAS Core Curriculum: A Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle Copyright 2007 by CANVAS. All rights reserved. The authors combine classic insights about nonviolent conflict with new ideas based on recent experience. The result is a synthesis that pushes the Published in Serbia, 2007. limits of what we thought nonviolent strategies were capable of achieving. The material covered includes time-tested analyses of power, different ISBN 978-86-7596-087-4 methods of nonviolent action, and ways to create a strategic plan for developing and mobilizing a movement. In addition, the authors include new material about how to: Publisher: Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS) • chart a movement’s history and progress (Chapter 8) Masarikova 5/ XIII, Belgrade, Serbia, www.canvasopedia.org • use marketing, branding, and effective communication techniques in a movement (Chapters 9 and 10) Graphic design and illustrations: Ana Djordjevic • address the effects of fear on a movement’s members (Chapter 13) • develop security measures within a movement (Chapter 14) Photo on cover: Igor Jeremic • manage a movement’s material resources, human resources, and time (Advanced Chapters 2-4) Throughout these topics, the authors emphasize pragmatic learning and draw on their own experience applying these ideas in their own struggles. -

CDDRL Number 114 WORKING PAPERS June 2009

CDDRL Number 114 WORKING PAPERS June 2009 Youth Movements in Post- Communist Societies: A Model of Nonviolent Resistance Olena Nikolayenko Stanford University Center on Democracy, Development, and The Rule of Law Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Additional working papers appear on CDDRL’s website: http://cddrl.stanford.edu. Center on Democracy, Development, and The Rule of Law Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Stanford University Encina Hall Stanford, CA 94305 Phone: 650-724-7197 Fax: 650-724-2996 http://cddrl.stanford.edu/ About the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL) CDDRL was founded by a generous grant from the Bill and Flora Hewlett Foundation in October in 2002 as part of the Stanford Institute for International Studies at Stanford University. The Center supports analytic studies, policy relevant research, training and outreach activities to assist developing countries in the design and implementation of policies to foster growth, democracy, and the rule of law. About the Author Olena Nikolayenko (Ph.D. Toronto) is a Visiting Postdoctoral Scholar and a recipient of the 2007-2009 post-doctoral fellowship from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Her research interests include comparative democratization, public opinion, social movements, youth, and corruption. In her dissertation, she analyzed political support among the first post-Soviet generation grown up without any direct experience with communism in Russia and Ukraine. Her current research examines why some youth movements are more successful than others in applying methods of nonviolent resistance to mobilize the population in non-democracies. She has recently conducted fieldwork in Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Serbia, and Ukraine. -

Revolutionary Tactics: Insights from Police and Justice Reform in Georgia

TRANSITIONS FORUM | CASE STUDY | JUNE 2014 Revolutionary Tactics: Insights from Police and Justice Reform in Georgia by Peter Pomerantsev with Geoffrey Robertson, Jovan Ratković and Anne Applebaum www.li.com www.prosperity.com ABOUT THE LEGATUM INSTITUTE Based in London, the Legatum Institute (LI) is an independent non-partisan public policy organisation whose research, publications, and programmes advance ideas and policies in support of free and prosperous societies around the world. LI’s signature annual publication is the Legatum Prosperity Index™, a unique global assessment of national prosperity based on both wealth and wellbeing. LI is the co-publisher of Democracy Lab, a journalistic joint-venture with Foreign Policy Magazine dedicated to covering political and economic transitions around the world. www.li.com www.prosperity.com http://democracylab.foreignpolicy.com TRANSITIONS FORUM CONTENTS Introduction 3 Background 4 Tactics for Revolutionary Change: Police Reform 6 Jovan Ratković: A Serbian Perspective on Georgia’s Police Reforms Justice: A Botched Reform? 10 Jovan Ratković: The Serbian Experience of Justice Reform Geoffrey Robertson: Judicial Reform The Downsides of Revolutionary Maximalism 13 1 Truth and Reconciliation Jovan Ratković: How Serbia Has Been Coming to Terms with the Past Geoffrey Robertson: Dealing with the Past 2 The Need to Foster an Opposition Jovan Ratković: The Serbian Experience of Fostering a Healthy Opposition Russia and the West: Geopolitical Direction and Domestic Reforms 18 What Georgia Means: for Ukraine and Beyond 20 References 21 About the Author and Contributors 24 About the Legatum Institute inside front cover Legatum Prosperity IndexTM Country Factsheet 2013 25 TRANSITIONS forum | 2 TRANSITIONS FORUM The reforms carried out in Georgia after the Rose Revolution of 2004 were Introduction among the most radical ever attempted in the post-Soviet world, and probably the most controversial. -

The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: a Strategic and Historical Analysis

ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: A Strategic and Historical Analysis Tenzin Dorjee ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES Cover photos: (l) John Ackerly, 1987, (r) Invisible Tibet Blog SERIES EDITOR: Maciej Bartkowski John Ackerly’s photo of the first major demonstration in Lhasa in 1987 CONTACT: [email protected] became an emblem for the Tibet movement. The monk Jampa Tenzin, who is being lifted by fellow protesters, had just rushed into a burning VOLUME EDITORS: Hardy Merriman, Amber French, police station to rescue Tibetan detainees. With his arms charred by the Cassandra Balfour flames, he falls in and out of consciousness even as he leads the crowd CONTACT: [email protected] in chanting pro-independence slogans. The photographer John Ackerly Other volumes in this series: became a Tibet advocate and eventually President of the International Campaign for Tibet (1999 to 2009). To read more about John Ackerly’s The Power of Staying Put: Nonviolent Resistance experience in Tibet, see his book co-authored by Blake Kerr, Sky Burial: against Armed Groups in Colombia, Juan Masullo An Eyewitness Account of China’s Brutal Crackdown in Tibet. (2015) Invisible Tibet Blog’s photo was taken during the 2008 Tibetan uprising, The Maldives Democracy Experience (2008-13): when Tibetans across the three historical provinces of Tibet rose up From Authoritarianism to Democracy and Back, to protest Chinese rule. The protests began on March 10, 2008, a few Velezinee Aishath (2015) months ahead of the Beijing Olympic Games, and quickly became the largest, most sustained nonviolent movement Tibet has witnessed. Published by the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict The designations used and material presented in this publication do P.O. -

The Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty

Public Diplomacy Division Room Nb123 B-1110 Brussels Belgium Tel.: +32(0)2 707 4414 / 5033 (A/V) Fax: +32(0)2 707 4249 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.nato.int/library Acquisitions List April 2013 New Books and Journal Articles Liste d’acquisitions Avril 2013 Nouveaux livres et articles de revues Division de la Diplomatie Publique Bureau Nb123 B-1110 Bruxelles Belgique Tél.: +32(0)2 707 4414 / 5033 (A/V) Fax: +32(0)2 707 4249 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.nato.int/library How to borrow items from the list below : As a member of the NATO HQ staff you can borrow books (Type: M) for one month, journals (Type: ART) and reference works (Type: REF) for one week. Individuals not belonging to NATO staff can borrow books through their local library via the interlibrary loan system. How to obtain the Multimedia Library publications : All Library publications are available both on the NATO Intranet and Internet websites. Comment emprunter les documents cités ci-dessous : En tant que membre du personnel de l'OTAN vous pouvez emprunter les livres (Type: M) pour un mois, les revues (Type: ART) et les ouvrages de référence (Type: REF) pour une semaine. Les personnes n'appartenant pas au personnel de l'OTAN peuvent s'adresser à leur bibliothèque locale et emprunter les livres via le système de prêt interbibliothèques. Comment obtenir les publications de la Bibliothèque multimédia : Toutes les publications de la Bibliothèque sont disponibles sur les sites Intranet et Internet de l’OTAN. -

A Dirty Affair Political Melodramas of Democratization

6 A Dirty Affair Political Melodramas of Democratization Ferdinand Marcos was ousted from the presidency and exiled to Hawaii in late February 1986,Confidential during a four-day Property event of Universitycalled the “peopleof California power” Press revolution. The event was not, as the name might suggest, an armed uprising. It was, instead, a peaceful assembly of thousands of civilians who sought to protect the leaders of an aborted military coup from reprisal by***** the autocratic state. Many of those who gathered also sought to pressure Marcos into stepping down for stealing the presi- dential election held in December,Not for Reproduction not to mention or Distribution other atrocities he had commit- ted in the previous two decades. Lino Brocka had every reason to be optimistic about the country’s future after the dictatorship. The filmmaker campaigned for the newly installed leader, Cora- zon “Cory” Aquino, the widow of slain opposition leader Ninoy Aquino. Despite Brocka’s reluctance to serve in government, President Aquino appointed him to the commission tasked with drafting a new constitution. Unfortunately, the expe- rience left him disillusioned with realpolitik and the new government. He later recounted that his fellow delegates “really diluted” the policies relating to agrarian reform. He also spoke bitterly of colleagues “connected with multinationals” who backed provisions inimical to what he called “economic democracy.”1 Brocka quit the commission within four months. His most significant achievement was intro- ducing the phrase “freedom of expression” into the constitution’s bill of rights and thereby extending free speech protections to the arts. Three years after the revolution and halfway into Mrs. -

YUGOSLAV REFUGEES, DISPLACED PERSONS and the CIVIL WAR Mirjana Morokvasic Freie Universitm, Berlin and Centre Nationale De La Recherche Scientifique, Paris

YUGOSLAV REFUGEES, DISPLACED PERSONS AND THE CIVIL WAR Mirjana Morokvasic Freie UniversitM, Berlin and Centre Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris Background case among the socialist countries. The within the boundaries of former Slovenia and Croatia declared present tragedy can only be compared Yugoslavia, the Yugoslav case may also independence on 25 June 1991. That to that of the Second World War; from help de-dramatize the East I West was the date of the "collective an international perspective, the invasion scenarios which predict thanatos"' which led to the United Nations High Commission on disruptive mass movements caused by disintegration of Yugoslavia. As a Refugees (UNHCR) compares it in political and ethnic violence or result of German pressure, the scope, scale of atrocities and ecological catastrophe in the countries European Community, followed by a consequences for the population, to the aligned with the former Soviet empire. number of other states, recognized the Cambodian civil war. The Demographic Structure In three ways, analyzing the independence of the secessionist The 600,000 to 1 million displaced refugees' situation contributes to our republics on 15 January 1992 and persons referred to above come from understanding of issues beyond the buried the second Y~goslavia.~ Croatia, whose total population is 4.7 human tragedy of the people Although the Westernmedia have million (see Figure 1).Moreover, most themselves. First, it demystifies the now shifted their attention to the of these people come from a relatively genesis of the Yugoslav conflict, which former Soviet Union, where other small area the front line, which is now is often reduced to a matter "ethnic - similar and potentially even more under the control of the Yugoslav hatred." It shows that the separation of dangerous ethnic conflicts are brewing, Army and Serbian forces.