PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joop Den Uyl Special in Argus.Pdf

Kok Joop steekt banaan in de fik Pagina 32 Jaargang 1, nummer 20 12 december 2017 Verschijnt tweewekelijks Losse nummers € 3, – Joop den Uyl, staatsman Dertig jaar na zijn dood komt Joop den Uyl tot leven in een speciale uitneembare bijlage. Socialist die de utopie niet kon missen. De constante in zijn politieke denken. Maar ook: de grootvader, de wanhopige, de ontroerende, de rechtlijnige, de lompe, de onbevangen figuur. Minister Bram Stemerdink over Joops afschuwelijkste momenten. Fotografen kiezen hun meest l e z veelzeggende plaat. t n e De gesneefde biograaf doet een boekje m t open. En nog veel meer. n e c n i v De volgende Argus verschijnt op 9 januari. o t o Vandaar dit extra dikke nummer. f 2017, alvast een terugblik: Rutte misleidt met belasting- voordeel. Leeuwarden koketteert met met beroemdheden die hun heil elders zochten. Oudere werknemers vertrouwen de zaak niet meer. Pagina 2-4 Belastingdeal Verkeerde onderzoekers vonden niks. Pagina 5 Zimbabwe: Wat Sally deed, liet Grace na. Pagina 6 Cyaankali Toneelstukje Praljak houdt conflict levend. Pagina 7 Philipp Blom Gaan! Alarm waar geen speld De niet te missen film. De tussen te krijgen is. overtuigende expo. Het Pagina 28 meest kersterige concert. Het verrassende boek. Word abonnee: Voortaan: Argus-tips. www.argusvrienden.nl Pagina 29 2017 12 december 2017 / 2 12 december 2017 / 3 Zes vaste medewerkers van Argus’ De dode mus van Rutte III binnenlandpagina’s kregen de Think global, vraag: Wat vind jij het meest door FLIP DE KAM hele begrotingsoverschot uit het act local basispad te ‘verjubelen’. opmerkelijke van 2017? et is domweg onmogelijk op het basispad stijgen de col - door NICO HAASBROEK donut - één gebeurtenis te noemen lectieve lasten in de komende kabi - model for - Hdie economie en over - netsperiode met vijf miljard euro. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/44001 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2018-07-07 and may be subject to change. Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2007 De moeizame worsteling met de Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2007 De moeizame worsteling met de nationale identiteit Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis De moeizame worsteling met de nationale identiteit Redactie: C.C. van Baaien A.S. Bos W. Breedveld M.H.C.H. Leenders J.J.M. Ramakers W.P. Secker Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Boom - Amsterdam Foto omslag: a n p - Robert Vos Omslag en binnenwerk: Wim Zaat, Moerkapelle Druk en afwerking: Drukkerij Wilco, Amersfoort © 2007 Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uitzonderingen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. No part ofthis book may be reproduced in any way whatsoever without the written permission of the publisher. isb n 978 90 8506 506 7 NUR 680 wvw.uitgeverijboom.nl Inhoud Ten geleide 7 Artikelen Dick Pels, De Hollandse tuin: of hoe de Nederlandse Leeuw worstelt met zijn iden 13 titeit Remieg Aerts, Op gepaste afstand. De plaats van het parlement in de natievorming 25 van de negentiende eeuw Charlotte Brand en Nicoline van der Sijs, Geen taal, geen natie. -

Theorizing the Urban Housing Commons

Th eorizing the urban housing commons Don Nonini Abstract: Th is article theorizes the making and unmaking of the urban housing commons in Amsterdam. Th e article reviews the literature on the urban housing commons, sets out the analytics of use values and exchange values for housing, and situates these analytics within the transition from dominance of industrial to fi nance capital in the Netherlands during neoliberalization from the mid-1970s to the present. A vibrant housing commons in Amsterdam came into existence by the 1980s because of two social movements that pressed the Dutch state to institu- tionalize this commons—the New Left movement within the Dutch Labor Party, and the squatters’ movement in Amsterdam. Th e subsequent shift in dominance from industrial to fi nance capital has led to the decline of both movements and the erosion of the housing commons. Keywords: Amsterdam, fi nance capital, neoliberalization, New Left movement, squatters’ movement, urban commons Th is article theorizes the urban commons in the oretical approach anchored in an analytics for case of the housing commons of Amsterdam, theorizing the making and unmaking of the the Netherlands, from the 1960s to the present. commons. In the second section, I provide evi- Th e making and unmaking of urban commons dence for the existence of a housing commons like housing in Amsterdam can only be under- in Amsterdam in the mid-1980s. Th e third sec- stood if urban commons are theorized both in tions applies the theoretical concepts of the terms of their scaled political economy and of article to explain the making of the housing com- the everyday interventions of social movement mons—the particular developments in postwar actors, as their actions were channeled by but capitalism in the Netherlands from the 1960s also transformed the historically and geograph- to the 1980s that empowered two diff erent so- ically specifi c arrangements between classes and cial movements to transform the Dutch state the modern state that constituted that political to establish the housing commons. -

Urban Europe Fifty Tales of the City Mamadouh, V.; Van Wageningen, A

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Urban Europe Fifty Tales of the City Mamadouh, V.; van Wageningen, A. DOI 10.26530/OAPEN_623610 Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version License CC BY-NC-ND Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Mamadouh, V., & van Wageningen, A. (Eds.) (2016). Urban Europe: Fifty Tales of the City. AUP. https://doi.org/10.26530/OAPEN_623610 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:29 Sep 2021 omslag Urban Europe.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10/11/16 / 13:03 | Pag. All Pages In Urban Europe, urban researchers and practitioners based in Amsterdam tell the story of the European city, sharing their knowledge – Europe Urban of and insights into urban dynamics in short, thought- provoking pieces. -

Urban Europe.Indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10/11/16 / 13:03 | Pag

omslag Urban Europe.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10/11/16 / 13:03 | Pag. All Pages In Urban Europe, urban researchers and practitioners based in Amsterdam tell the story of the European city, sharing their knowledge – Europe Urban of and insights into urban dynamics in short, thought- provoking pieces. Their essays were collected on the occasion of the adoption of the Pact of Amsterdam with an Urban Agenda for the European Union during the Urban Europe Dutch Presidency of the Council in 2016. The fifty essays gathered in this volume present perspectives from diverse academic disciplines in the humanities and the social sciences. Fifty Tales of the City The authors — including the Mayor of Amsterdam, urban activists, civil servants and academic observers — cover a wide range of topical issues, inviting and encouraging us to rethink citizenship, connectivity, innovation, sustainability and representation as well as the role of cities in administrative and political networks. With the Urban Agenda for the European Union, EU Member States of the city Fifty tales have acknowledged the potential of cities to address the societal challenges of the 21st century. This is part of a larger, global trend. These are all good reasons to learn more about urban dynamics and to understand the challenges that cities have faced in the past and that they currently face. Often but not necessarily taking Amsterdam as an example, the essays in this volume will help you grasp the complexity of urban Europe and identify the challenges your own city is confronting. Virginie Mamadouh is associate professor of Political and Cultural Geography in the Department of Geography, Planning and International Development Studies at the University of Amsterdam. -

Work in Progress

Harm Kaal Work in Progress Class and Voter Interaction in Election Campaigns of Dutch Social Democrats, c. 1945 to the 1970s Abstract: This article discusses the post-war history of the Dutch social-dem- ocratic Partij van de Arbeid. It takes as its point of departure the fact that the two elements at the heart of contemporary discussions about the future of social democracy – struggles over the definition of its constituency, par- ticularly the role class should play in it, and attempts to revitalize its interac- tion with the electorate – are present throughout the post-war history of the PvdA. The article explores both the content and mode of political represen- tation: it investigates the representative claims of the Dutch social democrats and the communicative practices through which these claims were made in order to establish how the PvdA imagined and tried to constitute its constit- uency. Who, which groups of voters, were the social democrats claiming to represent? How did they try to reach voters? How did their interaction with the electorate develop against the background of the rise of – new forms of – mass media? Keywords: social democracy – the Netherlands – electoral culture – political representation On 15 March 2017, Dutch voters inflicted a crushing defeat on the social democratic Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA): only 9 social democratic MPs – out of a total of 150 – were elected. Five years earlier, the PvdA had won 38 seats in the general elections and had become the second biggest party in parliament. Subsequently, the social democrats had entered into a coalition government with the liberal party Volkspar- tij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (in short: VVD). -

Herstel, Vernieuw En Verbreed De Bestaanszekerheid

57 Herstel, vernieuw en verbreed de bestaanszekerheid We zitten midden in de storm, en de gevolgen van de huidige crisis zullen wereldwijd nog wel een tijd voelbaar blijven. Juist nu is het belangrijk onze grondwaarden overtuigend gestalte te geven. De overheid mag dan diepe zakken hebben, we moeten niet vergeten hoe die diepe zakken zijn ontstaan en hoe hoog de prijs is geweest die daarvoor in recente jaren door de bevolking is betaald in de vorm van draconische bezuinigingen. J.TH.J. VAN DEN BERG Oud-directeur van de WBS en emeritus-hoogleraar parlementaire geschiedenis (Leiden) en parlementair stelsel (Maastricht) De kracht van de sociaal-democratie heeft academische opleiding. Tegelijk is de oude steeds gelegen in haar karakter als allian- arbeidersklasse sterk gekrompen door de tie van wat ooit de ‘nieuwe middenstand’ de-industrialisatie van ons land. Deze groep heette en de industriële arbeidersklasse.1 is inmiddels verdeeld over werknemers in Die alliantie tussen bevoorrechte en minder de resterende industrie, de bouwnijverheid bevoorrechte maatschappelijke groepen is en de sterk gegroeide dienstverlening. Het helaas verbroken. De nieuwe middenstand gaat meestal om laag gewaardeerde maar noemen we nu eerder de ‘intellectuele mid- wel noodzakelijke arbeid, vaak verricht denklasse’, en de industriële arbeidersklasse door migranten en hun nakomelingen. De is onderdeel geworden van wat wij nu de oude arbeidersklasse heeft nog maar weinig ‘middenklasse’ noemen en waarbij eerder onderlinge samenhang. Niet toevallig heeft moet worden gedacht aan enerzijds de goed de vakbeweging in de loop van de laatste de- opgeleide industriearbeiders en anderzijds cennia dan ook veel aan kracht en betekenis de ambachtelijk gevormde vrouwen en man- verloren. -

Personalization of Political Newspaper Coverage: a Longitudinal Study in the Dutch Context Since 1950

Personalization of political newspaper coverage: a longitudinal study in the Dutch context since 1950 Ellis Aizenberg, Wouter van Atteveldt, Chantal van Son, Franz-Xaver Geiger VU University, Amsterdam This study analyses whether personalization in Dutch political newspaper coverage has increased since 1950. In spite of the assumption that personalization increased over time in The Netherlands, earlier studies on this phenomenon in the Dutch context led to a scattered image. Through automatic and manual content analyses and regression analyses this study shows that personalization did increase in The Netherlands during the last century, the changes toward that increase however, occurred earlier on than expected at first. This study also shows that the focus of reporting on politics is increasingly put on the politician as an individual, the coverage in which these politicians are mentioned however became more substantive and politically relevant. Keywords: Personalization, content analysis, political news coverage, individualization, privatization Introduction When personalization occurs a focus is put on politicians and party leaders as individuals. The context of the news coverage in which they are mentioned becomes more private as their love lives, upbringing, hobbies and characteristics of personal nature seem increasingly thoroughly discussed. An article published in 1984 in the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf forms a good example here, where a horse race betting event, which is attended by several ministers accompanied by their wives and girlfriends is carefully discussed1. Nowadays personalization is a much-discussed phenomenon in the field of political communication. It can simply be seen as: ‘a process in which the political weight of the individual actor in the political process increases 1 Ererondje (17 juli 1984). -

Pvda Jv 1976-77.Pdf

DOCUMENT ATIECE!~tRWVI Blz. NEDERLANDS-!: POLITIEKE 1 PAflrTIJëN Inleiding 3-4 Samenstelling partijbestuur 6 Samenstelling partijsekretariaat 6-7 Ledenadministratie en kontributie-inning 8 Ledenverloop 9-12 Partijpers:-Algemene redaktie 13 -Partijkrant 13 -Roos in de Vuist 13-14 Kommissies 15-18 Partijraden 18-25 Verkiezingen: Tweede Kamer:-Kandidaatstelling 26-35 -Aktie 36-38 Eerste Kamer 38-39 Akties:-Landelijke werkgroep bedrijfsdemokra tisering 40-44 -Werkgroep volkshuisvesting 44-45 -Ombudswerk 45 PvdA-komitee tegen de Berufsverbote 46-47 Internationaal sekretariaat 48-49 Federatie van Jongerengroepen 50-57 Rooie Vrouwen 58-70 Wiardi Beekman Stichting 7l-ll1 Stichting Vormingswerk PvdA 112-146 Evert Vermeer Stichting 147-156 Centrum voor Levensbeschouwing en Politiek 157-160 1 INLEIDING Bij het doorlezen van het organisatorisch verslag over het verenigingsjaar 1976-1977 zijn er een paar dingen die dus danig opvallen, dat zij de moeite van het vermelden indeze inleiding waard zijn. Allereerst dient in dit verband gewezen te worden op de positieve ontwikkeling van het ledenverloop. In de inlei ding op het vorig verslag werd van die ontwikkeling al melding gemaakt, maar moest vanzelfsprekend nog een slag om de arm worden gehouden. Thans kan zonder enige terughoudendheid worden gekonsta teerd, dat de partij in het verenigingsjaar 1976-1977 een ledenwinst boekte van ruim 14.000 (een aantal dat inmiddels bij het schrijven van deze woorden is gestegen tot boven de 20.000). Deze ledenwinst, die zich vooral uitte na de val van het kabinet-Den Uyl (medio maart 1977), is het meest kenmerk ende teken van het feit dat de Partij van de Arbeid een springlevende organisatie is, die -het verslag staat er vol van- een veelheid van taken tracht te vervullen, en veelal niet zonder sukses. -

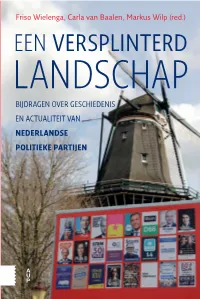

Een Versplinterd Landschap Belicht Deze Historische Lijn Voor Alle Politieke NEDERLANDSE Partijen Die in 2017 in De Tweede Kamer Zijn Gekozen

Markus Wilp (red.) Wilp Markus Wielenga, CarlaFriso vanBaalen, Friso Wielenga, Carla van Baalen, Markus Wilp (red.) Het Nederlandse politieke landschap werd van oudsher gedomineerd door drie stromingen: christendemocraten, liberalen en sociaaldemocraten. Lange tijd toonden verkiezingsuitslagen een hoge mate van continuïteit. Daar kwam aan het eind van de jaren zestig van de 20e eeuw verandering in. Vanaf 1994 zette deze ontwikkeling door en sindsdien laten verkiezingen EEN VERSPLINTERD steeds grote verschuivingen zien. Met de opkomst van populistische stromingen, vanaf 2002, is bovendien het politieke landschap ingrijpend veranderd. De snelle veranderingen in het partijenspectrum zorgen voor een over belichting van de verschillen tussen ‘toen’ en ‘nu’. Bij oppervlakkige beschouwing staat de instabiliteit van vandaag tegenover de gestolde LANDSCHAP onbeweeglijkheid van het verleden. Een dergelijk beeld is echter een ver simpeling, want ook in vroeger jaren konden de politieke spanningen BIJDRAGEN OVER GESCHIEDENIS hoog oplopen en kwamen kabinetten regelmatig voortijdig ten val. Er is EEN niet alleen sprake van discontinuïteit, maar ook wel degelijk van een doorgaande lijn. EN ACTUALITEIT VAN VERSPLINTERD VERSPLINTERD Een versplinterd landschap belicht deze historische lijn voor alle politieke NEDERLANDSE partijen die in 2017 in de Tweede Kamer zijn gekozen. De oudste daarvan bestaat al bijna honderd jaar (SGP), de jongste partijen (DENK en FvD) zijn POLITIEKE PARTIJEN nagelnieuw. Vrijwel alle bijdragen zijn geschreven door vertegenwoordigers van de wetenschappelijke bureaus van de partijen, waardoor een unieke invalshoek is ontstaan: wetenschappelijke distantie gecombineerd met een beschouwing van ‘binnenuit’. Prof. dr. Friso Wielenga is hoogleraardirecteur van het Zentrum für NiederlandeStudien aan de Westfälische Wilhelms Universität in Münster. LANDSCHAP Prof. -

Den Uyl, Lay-Out

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Joop den Uyl 1919-1987 : dromer en doordouwer Bleich, A. Publication date 2008 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Bleich, A. (2008). Joop den Uyl 1919-1987 : dromer en doordouwer. Uitgeverij Balans. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:01 Oct 2021 Den Uyl-revisie 18-01-2008 10:08 Pagina 266 Hoofdstuk 11 Rood met een witte rand Eind 1972 waren er verkiezingen voor deTweede Kamer.Het vijfpartijen- kabinet onder de Antirevolutionaire premier Barend Biesheuvel was ten onder gegaan aan een conflict van liberalen en confessionelen met de partij van de jonge Drees. De ds’70-ministers wilden de bezuinigingen waar ze vóór waren niet zelf voor hun rekening nemen. -

B BOOM115 Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2017 Binnenwerk BW.Indd

Bos, A.S., Brouwer, J.W.L., Goslinga, H., Oddens, J., Ramakers, J.J.M. & Reiding, H. (red.). (2017). Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2017. Het volk spreekt. Amsterdam: Boom uitgevers Amsterdam Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2017 Het volk spreekt Bos, A.S., Brouwer, J.W.L., Goslinga, H., Oddens, J., Ramakers, J.J.M. & Reiding, H. (red.). (2017). Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2017. Het volk spreekt. Amsterdam: Boom uitgevers Amsterdam Bos, A.S., Brouwer, J.W.L., Goslinga, H., Oddens, J., Ramakers, J.J.M. & Reiding, H. (red.). (2017). Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2017. Het volk spreekt. Amsterdam: Boom uitgevers Amsterdam Het volk spreekt Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2017 Redactie: Anne Bos Jan Willem Brouwer Hans Goslinga Joris Oddens Jan Ramakers Hilde Reiding Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis Nijmegen Boom – Amsterdam Bos, A.S., Brouwer, J.W.L., Goslinga, H., Oddens, J., Ramakers, J.J.M. & Reiding, H. (red.). (2017). Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2017. Het volk spreekt. Amsterdam: Boom uitgevers Amsterdam Afbeelding omslag: Demonstratie voor een beter ouderenbeleid, januari 1982 [nationaal archief] Vormgeving: Boekhorst Design, Culemborg © 2017 Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uitzonderingen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektro- nisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, zonder vooraf- gaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. No part of this book may be reproduced in any way whatsoever without the written permission of the publisher. isbn 9789024415731 nur 680 www.boomgeschiedenis.nl www.bua.nl Bos, A.S., Brouwer, J.W.L., Goslinga, H., Oddens, J., Ramakers, J.J.M.