6 Prolegomena to a Kilivila Grammar of Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tuma Underworld of Love. Erotic and Other Narrative Songs of The

The Tuma Underworld of Love Erotic and other narrative songs of the Trobriand Islanders and their spirits of the dead Culture andCulture Language Use Gunter Senft guest IP: 195.169.108.24 On: Tue, 01 Aug 2017 13:36:03 5 John Benjamins Publishing Company The Tuma Underworld of Love Underworld Tuma The guest IP: 195.169.108.24 On: Tue, 01 Aug 2017 13:36:03 Culture and Language Use Studies in Anthropological Linguistics CLU-SAL publishes monographs and edited collections, culturally oriented grammars and dictionaries in the cross- and interdisciplinary domain of anthropological linguistics or linguistic anthropology. The series offers a forum for anthropological research based on knowledge of the native languages of the people being studied and that linguistic research and grammatical studies must be based on a deep understanding of the function of speech forms in the speech community under study. For an overview of all books published in this series, please see http://benjamins.com/catalog/clu Editor Gunter Senft Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen guest IP: 195.169.108.24 On: Tue, 01 Aug 2017 13:36:03 Volume 5 The Tuma Underworld of Love. Erotic and other narrative songs of the Trobriand Islanders and their spirits of the dead by Gunter Senft The Tuma Underworld of Love Erotic and other narrative songs of the Trobriand Islanders and their spirits of the dead Gunter Senft Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics guest IP: 195.169.108.24 On: Tue, 01 Aug 2017 13:36:03 John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984. -

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands First compiled by Nancy Sack and Gwen Sinclair Updated by Nancy Sack Current to January 2020 Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands Background An inquiry from a librarian in Micronesia about how to identify subject headings for the Pacific islands highlighted the need for a list of authorized Library of Congress subject headings that are uniquely relevant to the Pacific islands or that are important to the social, economic, or cultural life of the islands. We reasoned that compiling all of the existing subject headings would reveal the extent to which additional subjects may need to be established or updated and we wish to encourage librarians in the Pacific area to contribute new and changed subject headings through the Hawai‘i/Pacific subject headings funnel, coordinated at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.. We captured headings developed for the Pacific, including those for ethnic groups, World War II battles, languages, literatures, place names, traditional religions, etc. Headings for subjects important to the politics, economy, social life, and culture of the Pacific region, such as agricultural products and cultural sites, were also included. Scope Topics related to Australia, New Zealand, and Hawai‘i would predominate in our compilation had they been included. Accordingly, we focused on the Pacific islands in Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia (excluding Hawai‘i and New Zealand). Island groups in other parts of the Pacific were also excluded. References to broader or related terms having no connection with the Pacific were not included. Overview This compilation is modeled on similar publications such as Music Subject Headings: Compiled from Library of Congress Subject Headings and Library of Congress Subject Headings in Jewish Studies. -

Nomenclature Abbreviations

Abbreviations * As a prefix, indicates a proto language word /?/ glottal stop 2′ compound for 3 = 2 + 1 or rarely 1 + 1 + 1 but numeral for 4 2″ distinct numeral for 3 but 4 is a compound, usually 2 + 2, rarely 5 - 1 or 2 + 1 + 1 AN Austronesian languages BC or BCE Before Christ, that is before the Current Era taken as before the period of Christ BP Before the present CE or AD In the current era, that is after the year of the Lord (Domino/Dominum) Christ CSQ, MQ Counting System Questionnaire; Measurement Questionnaire d. dialect IMP Indigenous Mathematics Project Manus type Lean used this to refer to counting systems that used subtraction from 10 such as 7=10-3, 8=10-2, 9=10-1, often with the meaning e.g. for 7 as 3 needed to com- plete the group MC Micronesian Motu type Lean used this to refer to counting systems that used pairs such as 6=2x3, 7=2x3+1, 8=2x4, 9=2x4+1 NAN Non-Austronesian (also called Papuan) languages NCQ, CQN Noun, classifier, quantifier; classifier, quantifier, noun NQC, QCN Noun, quantifier, classifier; quantifier, classifier, noun NTM New Tribes Mission, PNG PAN Proto Austronesian PN Polynesian PNG Papua New Guinea POC Proto Oceanic QC, CQ Order of quantifier-classifier; classifier-quantifier respectively SHWNG South Halmahera West New Guinea (AN Non-Oceanic language of the Central- Eastern Malayo-Polynesian, a subgroup of Proto-Malayo-Polynesian) after Tryon (2006) SIL Summer Institute of Linguistics SOV Order of words in a sentence: Subject Object Verb SVO Order of words in a sentence: Subject Verb Object TNG Trans New Guinea Phylum Nomenclature The Australian system of numbering is used. -

Language Change: Missionaries and Moribund Varieties Ofkilivila

5 Culture change -language change: missionaries and moribund varieties ofKilivila GlTNTER SENFT Ilavta pEl Kat OUOEV JJ£VEt HpaKM:lto<; 1 Introductionl When I frrst set foot on Trobriand Islands' soil in 1982 to start my first fifteen months of field research there I had the quite romantic feeling that it was like stepping right into the picture so vividly presented in Bronislaw Malinowski's ethnographic masterpieces published in the fITst quarter ofthe last century. However, by the time ofmy second period of field research in 1989 the situation had completely changed. During my various fieldtrips over the last 22 years I have noticed that the culture of the Trobriand Islanders has been changing rather dramatically, and it is an old and trivial insight that culture change must affect language and must itself be reflected in some way or other in the language ofthe speech community undergoing this change. After having returned from my second field trip to the Trobriands I described the changes I observed in 1989 with respect to the Trobriand Islanders' language and culture (see Senft 1992) - and, unfortunately and sadly, the pessimistic predictions I made then have proven to be right by now. But is 'language change' not one of the most important constitutive and defining features of every natural language? And what have ordinary and general dynamic processes of language change and their results to do with the topics of 'endangered languages' and 'language death'? These questions are central for this paper. In what follows I will first report on the general status of Kilivila with respect to levels of its endangerment (see Crystal 2000: 19ff.). -

C Cat Talo Ogu Ue

PACIF IC LINGUISTICS Catalogue February, 2013 Pacific Linguistics WWW Home Page: http://pacling.anu.edu.au/ Pacific Linguistics School of Culture, History and Language College of Asia and the Pacific THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY See last pagee for order form FOUNDING EDITOR: S.A. Wurm MANAGING EDITOR: Paul Sidwell [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD: I Wayan Arka, Mark Donohue, Bethwyn Evan, Nicholas Evans, Gwendolyn Hyslop, David Nash, Bill Palmer, Andrew Pawley, Malcolm Ross, Paul Sidwell, Jane Simpson, and Darrell Tryon ADDRESS: Pacific Linguistics School of Culture, History and Language College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 Australia Phone: +61 (02 6125 2742 E-mail: [email protected] Home page: http://www.pacling.anu.edu.au// 1 2 Pacific Linguistics Pacific Linguistics Books Online http://www.pacling.anu.edu.au/ Austoasiatic Studies: PL E-8 Papers from ICAAL4: Mon-Khmer Studies Journal, Special Issue No. 2 Edited by Sophana Srichampa & Paul Sidwell This is the first of two volumes of papers from the forth International Conference on Austroasiatic Linguistics (ICAAL4), which was held at the Research Institute for Language and Culture of Asia, Salaya campus of Mahidol University (Thailand) 29-30 October 2009. Participants were invited to present talks related the meeting theme of ‘An Austroasiatic Family Reunion’, and some 70 papers were read over the two days of the meeting. Participants came from a wide range of Asian countries including Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Singapore and China, as well as western nations. Published by: SIL International, Dallas, USA Mahidol University at Salaya, Thailand / Pacific Linguistics, Canberra, Australia ISBN 9780858836419 PL E-7 SEALS XIV Volume 2 Papers from the 14th annual meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 2004 Edited by Wilaiwan Khanittanan and Paul Sidwell The Fourteenth Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society was held in Bangkok , Thailand , May 19-21, 2004. -

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Homology theory Ka nanʻʺ (Burmese people) (May Subd Geog) USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) NT Whitehead groups [DS528.2.K2] K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) K. Tzetnik Award in Holocaust Literature UF Ka tūʺ (Burmese people) USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Ka-Tzetnik Award BT Ethnology—Burma K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) Peras Ḳ. Tseṭniḳ ʾKa nao dialect (May Subd Geog) UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) Peras Ḳatseṭniḳ BT China—Languages K9 (Fictitious character) BT Literary prizes—Israel Hmong language K 37 (Military aircraft) K2 (Pakistan : Mountain) Ka nō (Burmese people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) UF Dapsang (Pakistan) USE Tha noʹ (Burmese people) K 98 k (Rifle) Godwin Austen, Mount (Pakistan) Ka Rang (Southeast Asian people) USE Mauser K98k rifle Gogir Feng (Pakistan) USE Sedang (Southeast Asian people) K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 Mount Godwin Austen (Pakistan) Ka-taw USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Mountains—Pakistan USE Takraw K.A. Lind Honorary Award Karakoram Range Ka Tawng Luang (Southeast Asian people) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris K2 (Drug) USE Phi Tong Luang (Southeast Asian people) K.A. Linds hederspris USE Synthetic marijuana Kā Tiritiri o te Moana (N.Z.) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris K3 (Pakistan and China : Mountain) USE Southern Alps/Kā Tiritiri o te Moana (N.Z.) K-ABC (Intelligence test) USE Broad Peak (Pakistan and China) Ka-Tu USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children K4 (Pakistan and China : Mountain) USE Kha Tahoi K-B Bridge (Palau) USE Gasherbrum II (Pakistan and China) Ka tūʺ (Burmese people) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) K4 Locomotive #1361 (Steam locomotive) USE Ka nanʻʺ (Burmese people) K-BIT (Intelligence test) USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) Ka-Tzetnik Award USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test K5 (Pakistan and China : Mountain) USE K. -

2018Wissedcjphdvol1 Copy

ALL THINGS TROBRIAND A portrait of Dr. G. J. M. (Fred) Gerrits’ Trobriand Island collections, 1968 to 1972 Volume I Désirée C. J. Wisse October 2018 Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sainsbury Research Unit For the Arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas, University of East Anglia © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived therefrom must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Student number: 6355714 Abstract Dr. G.J.M. Gerrits was stationed on the Trobriand Islands as the Medical Officer between 1968 and 1971. In this period he collected approximately 3000 artefacts from the Trobriand Islands and the surrounding region. Approximately two- thirds of these objects are presently held in museums in Europe, Australia and Papua New Guinea. The study places Gerrits’ collection into a historical context of Trobriand collecting encounters and gains insights into ethnographic collection formation, considering various aspects of collecting. These include a collector’s multiple motives (Grijp, 2006), the desire to collect (complete) series of objects and unique pieces (Baudrillard 1994, Elsner and Cardinal, 1994) and differences between stable and mobile collecting (O‘Hanlon, 2000: 15). The study utilises Gerrits’ documentation, the collections of artefacts and photographs, conversations with Gerrits, Trobriand Islanders and other collectors, and draws on the literature on collecting research and publications containing information on Trobriand Island contact history. -

Organised Phonology Data

Organised Phonology Data Kiriwina [Kavataria dialect] (Kilivila) Language [KIJ] Milne Bay Province Oceanic; Papuan Tip Cluster; Peripheral Papuan Tip; Kilivila Chain Population census: 5000 (15000 all language) Major villages: Islands: Kiriwina, Kuia, Munuwata, Simsim, Kaileuna Linguistic work done by: UC, G.Senft, Ralph Lawton etc. Data checked by: Phonemic and Orthographic Inventory a b b d e i k k l m m n o p p s t a b bw d e g gw i k kw l m mw n o p pw r s t A B Bw D E G Gw I K Kw L M Mw N O P Pw R S T u w j u v w y U V W Y Consonants Bilab LabDen Dental Alveo Postalv Retro Palatal Velar Uvular Pharyn Glottal Plosive p b t d k Nasal m n Trill Tap/Flap Fricative s Lateral Fricative Approx j Lateral l Approx Ejective Stop Implos /w/ voiced labial-velar approximant /p/ voiceless labialised bilabial plosive /b / voiced labialised bilabial plosive /m/ voiced labialised bilabial nasal /k/ voiceless labialised velar plosive // voiced labialised velar plosive Kiriwina [Kavataria dialect] (Kilivili) OPDPrinted: August 25, 2004 Page 2 rigariga 'plant sp.' p paka 'feast' r popu 'excrement' karaga 'parrot spec.' - - mpana 'that (piece)' kampaya 'umpire' n natu 'tree sp.' momona 'semen' p pwaka 'lime' - mapwana 'that (filth)' mnumonu 'grass' - kamnomwana 'to boast' latula 'his offspring' b bala 'I will go' l bobu 'cut' momola 'fat' - - ambaisa 'where?' mlopu 'cave' sala 'his friends' b bwala 'house' s kwaibwaga 'wind from west, west' pasa 'swamp' - - mbwailila 'his loved item' mseu 'smoke' simsimwai 'sweet potato' m masawa 'canoe' tamagu -

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands First compiled by Nancy Sack and Gwen Sinclair Updated by Nancy Sack Current to December 2014 A Kinum (Papua New Guinean people) Great Aboré Reef (New Caledonia) USE Kaulong (Papua New Guinean people) Récif Aboré (New Caledonia) A Kinum language BT Coral reefs and islands—New Caledonia USE Kaulong language Abui language (May Subd Geog) A Kinun (Papua New Guinean people) [PL6621.A25] USE Kaulong (Papua New Guinean people) UF Barawahing language A Kinun language Barue language USE Kaulong language Namatalaki language A’ara language BT Indonesia—Languages USE Cheke Holo language Papuan languages Aara-Maringe language Abulas folk songs USE Cheke Holo language USE Folk songs, Abulas Abaiang Atoll (Kiribati) Abulas language (May Subd Geog) UF Abaiang Island (Kiribati) UF Abelam language Apaia (Kiribati) Ambulas language Apaiang (Kiribati) Maprik language Apia (Kiribati) BT Ndu languages Charlotte Island (Kiribati) Papua New Guinea—Languages Matthews (Kiribati) Acira language Six Isles (Kiribati) USE Adzera language BT Islands—Kiribati Adam Island (French Polynesia) Abaiang Island (Kiribati) USE Ua Pou (French Polynesia) USE Abaiang Atoll (Kiribati) Adams (French Polynesia) Abau language (May Subd Geog) USE Nuka Hiva (French Polynesia) [PL6621.A23] Ua Pou (French Polynesia) UF Green River language Adams Island (French Polynesia) BT Papuan languages USE Ua Pou (French Polynesia) Abelam (New Guinea tribe) Admiralties (Papua New Guinea) USE (Abelam (Papua New Guinean people) USE Admiralty -

Culture Change, Language Change

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series C-120 CULTURE CHANGE, LANGUAGE CHANGE CASE STUDIES FROM MELANESIA edited by Tom Dutton Published with financial assistance from the UNES CO Office for the Pacific Studies Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Dutton, T. editor. Culture change, language change: Case studies from Melanesia. C-120, viii + 164 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1992. DOI:10.15144/PL-C120.cover ©1992 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A: Occasional Papers SERIES C: Books SERIES B: Monographs SERIES D: Special Publications FOUNDING EDITOR: S.A. Wurrn EDITORIAL BOARD: K.A. Adelaar, T.E. Dutton, A.K. Pawley, M.D. Ross, D.T. Tryon EDITORIALADVISERS: B.W. Bender K.A. McElhanon University of Hawaii Summer Instituteof Linguistics David Bradley H.P. McKaughan La Trobe University University of Hawaii Michael G. Clyne P. Miihlhausler Monash University Linacre College, Oxford S.H. Elbert G.N. O' Grady University of Hawaii University of Victoria, B.C. KJ. Franklin K.L. Pike Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W. Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Texas G.W. Grace Gillian Sankoff University of Hawaii University of Pennsylvania M.A.K. Halliday W.A.L. Stokhof University of Sydney University of Leiden E. Haugen B.K. Tsou Harvard University City Polytechnic of Hong Kong A. -

Trobib 2011.Pdf

1 A Trobriand/Massim Bibliography Seventh Edition: July 2011 Allan C. Darrah Jay B. Crain The DEPTH Project: Department of Anthropology CSUS In 1965 Crain created the first Trobriand Bibliography which was updated in 1993 by Gardener and Darrah and expanded to include materials from other islands in the Massim. The 1995 edition was compiled by Darrah with the help of Claire Chiu and the members of the Trobriand Seminar at CSUS. In 1999 and again in 2000 Darrah was responsible for the updates. Darrah and Crain have completed this 2011 update. This bibliography is very much a work in progress, containing a few incomplete citations and no doubt many errors. Anyone who would like to make additions or corrections should contact Darrah [email protected] or Crain [email protected]. Criteria for inclusion of materials has been flexible in terms of both geography and subject matter. The geographic focus has always been the Trobriand Islands and neighboring societies associated with the kula; however, there are also items which focus on Milne Bay Province and Papua New Guinea. Even though there have been no limitations for inclusion based on subject matter the main thrust has been ethnography. One major exception to the geographic criteria has been made; works by and about major Massim scholars, which contain little or no information about the Massim, are included. The compilers wish to acknowledge major contributions made by Macintyre (1983) and more recently Hide (2000) and most especially the superb PNG bibliography of Terrance Hays (http://www.papuaweb.org/bib/hays/ng/index.html.) Important contributions were also made by Leach, J. -

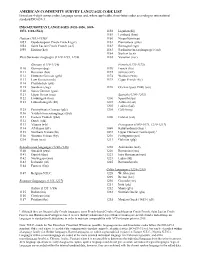

American Community Survey Language Code List

AMERICAN COMMUNITY SURVEY LANGUAGE CODE LIST Listed are 4-digit census codes, language names and, where applicable, three-letter codes according to international standard ISO 639-3. INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES (1053-1056, 1069- 1073, 1110-1564) 1158 Ligurian (lij) 1159 Lombard (lmo) Haitian (1053-1056)1 1160 Neapolitan (nap) 1053 Guadeloupean Creole French (gcf) 1161 Piemontese (pms) 1054 Saint Lucian Creole French (acf) 1162 Romagnol (rgn) 1055 Haitian (hat) 1163 Sardinian (macrolanguage) (srd) 1164 Sicilian (scn) West Germanic languages (1110-1139, 1234) 1165 Venetian (vec) German (1110-1124) French (1170-1175) 1110 German (deu) 1170 French (fra) 1111 Bavarian (bar) 1172 Jèrriais (nrf) 1112 Hutterite German (geh) 1174 Walloon (wln) 1113 Low German (nds) 1175 Cajun French (frc) 1114 Plautdietsch (ptd) 1115 Swabian (swg) 1176 Occitan (post 1500) (oci) 1120 Swiss German (gsw) 1121 Upper Saxon (sxu) Spanish (1200-1205) 1122 Limburgish (lim) 1200 Spanish (spa) 1123 Luxembourgish (ltz) 1201 Asturian (ast) 1202 Ladino (lad) 1125 Pennsylvania German (pdc) 1205 Caló (rmq) 1130 Yiddish (macrolanguage) (yid) 1131 Eastern Yiddish (ydd) 1206 Catalan (cat) 1132 Dutch (nld) 1133 Vlaams (vls) Portuguese (1069-1073, 1210-1217) 1134 Afrikaans (afr) 1069 Kabuverdianu (kea) 1 1135 Northern Frisian (frr) 1072 Upper Guinea Crioulo (pov) 1 1136 Western Frisian (fry) 1210 Portuguese (por) 1234 Scots (sco) 1211 Galician (glg) Scandinavian languages (1140-1146) 1218 Aromanian (aen) 1140 Swedish (swe) 1220 Romanian (ron) 1141 Danish (dan) 1221 Istro Romanian (ruo)