Journal Fnthpsy Number 31 Spring, 1980

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autunno 2018

NATURA E CULTURA editrice catalogo AUTUNNO 2018 www.naturaecultura.com Siamo una piccola realtà editoriale indipendente, dal 1989 pubblichiamo opere scelte in area antroposofica. Nel nostro catalogo trovate autori che hanno approfondito con dedizione e originalità le indicazioni di rudolf Steiner, fondatore dell’antroposofia. Fedeli alle nostre radici, la sfida che ci poniamo è di proporre libri coerenti ai valori che riteniamo importanti senza fermarci di fronte alle etichette. conoscenza, autoeducazione, esperienza concreta sono le nostre parole chiave. i temi prediletti sono la pedagogia e la genitorialità, la ricerca e lo sviluppo personale, l’alimentazione e la cura della salute, lo sguardo alla vivente natura, l’agricoltura biodinamica, il sociale. i nostri libri sono reperibili o ordinabili presso la vostra libreria preferita, nei negozi di prodotti naturali e biologici NaturaSì, nei bookshop online. Visitate la sezione librerie del nostro sito www.naturaecultura.com per scoprire i negozi che ci ospitano. i nostri contatti: NATURA E CULTURA EDITRICE società cooperativa tel.+39 338 5833907 / Fax +39 1782733370 e-mail [email protected] www.naturaecultura.com Naturaeculturaeditrice distributore nazionale per le librerie: o.N.B. old New Books distribuzioni editoriali Via a. Piutti, 2 – 33100 Udine tel. 0432 600987 / Fax 0432 600987 e-mail [email protected] aderisce al circuito FaSt Book e liBro.co 3 SalUte e Malattia. iN raPPorto a ViceNde UMaNe e karMiche rudolf Steiner Pag. 128, cm 14x21 - 3° edizione italiana, 2016 iSBN: 978-88-95673-36-3 € 12,00 ogni malattia è assimilabile a una disarmonia, a uno squilibrio tra l’uomo interiore e quello esteriore. -

Journal Fanthpsy Y OUTH LONGS to KNOW John F. Gardner

Journal forAnthroposophyYOUTH LONGS TO KNOW John F. Gardner GLIMPSES OF THE BUILDING Sonia Tomara Clark OF THE FIRST GOETHEANUM Jeannette Eaton FROM CONSUMER TO PRODUCER Herbert Witzenmann IN THE SPIRITUAL SPHERE ARCHETYPAL RELATIONS Wilhelm Pelikan BETWEEN PLANT AND MAN ALBERT STEFFEN: RETROSPECT Henry and Christy Barnes Also comments on a proposal to Governor Rockefeller, a review and poems by Floyd McKnight, Amos Franceschelli, Danilla Rettig, M. C. Richards and Claire Blatchford. NUMBER 14 AUTUMN, 1971 The spiritual investigator must not be in any sense a dreamer, a visionary. He must move with inner assurance and vigor in the spiritual world as an in telligent man does in the physical world. Rudolf Steiner Youth Longs to Know JOHN F. GARDNER “I am very content, with knowing, if only I could know." — Emerson Many children today bear within them greater potentialities than ever before, powers the world needs as never before. Educators and parents must recognize and find ways to encourage these new capacities. The schooling and habits of thought to which children are now exposed, however, are not helpful. They frustrate what longs to be fulfilled. Our civilization as a whole represents a concerted attack upon the potentialities of the new generations. We must help youth to withstand this attack. We must make it possible for young people to realize the purpose of their lives: to achieve what they mean to achieve. And the modern world must receive from them just what they alone can newly give, if it is to solve the human and environmental problems that increasingly beset it. -

Centre Guy Lorge « Eveil En Rencontres »

IDCCH ASBL (Initier, Développer, Connaître, Cultiver, Humaniser) Centre Guy Lorge « Eveil en Rencontres » Librairie associative—Centre de Documentation Rue du Centre, 12 B-4560 Auvelais (Sambreville) Renseignements : +32 (0)494 789 048 Courrier et commandes : [email protected] https://www.idcch.be Date : 01/09/2018 Page 2 Guy Lorge Aussi accessible 2ème édition à nos membres mai 2014 en prêt du livre dans notre centre ô homme, connais-toi toi-même et deviens toi-même ! exhortation que l'homme s'adresse à lui-même 17,00 € éveil en rencontres dans notre librairie Le livre: I D C C H — CENTRE GUY LORGE Page 3 L'auteur: Page 4 PRINTEMPS 1953- TRIADES 1 - N°1 : S. Rihouet-Coroze : ÉTÉ 1953 - TRIADES 1 - N°2 : S. Rihouet-Coroze : I D C C H — CENTRE GUY LORGE Page 5 AUTOMNE 1953- TRIADES 1 - N°3 : Emile Rinck : : HIVER 1953 - TRIADES 1 - N°4 Paul Coroze : Pierre Morizot : Ernest Uehli : Dr Fred Husemann : F. Bessenich : Page 6 PRINTEMPS 1954 - TRIADES 2 - N°1 G. Wachsmuth : Emile Rinck: Jacques Lusseyran : Dr Husemann : S.R.C. : ÉTÉ 1954 - TRIADES 2 - N°2 S. Rihouet-Coroze : Emile Rinck : Pierre Lusseyran : Maurice Leblanc : Paul Coroze : H. Poppel baum : I D C C H — CENTRE GUY LORGE Page 7 AUTOMNE 1954- TRIADES 2 - N°3 : Raymond Burlotte: Hildegarde Gerbert : HIVER 1954 - TRIADES 2 - N°4 Emile Rinck : Paul Coroze : S. Rihouet-Coroze : Jean-Denis : Dr Gérard Schmidt : Page 8 PRINTEMPS 1955- TRIADES 3 N°1 Dr E. Marti : Naissance d’un enfant. Emile Rinck : L’homme en face de la matière. -

Anthroposophie Als Frühe Chronologiekritik

Andreas Ferch Anthroposophie als frühe Chronologiekritikund okkulte Geschichtsforschung (2) In diesem Beitrag geht es darum, die Frage nach Geschichte und ihrer Chronologie einmal mit der esoterischen Weltanschau- ung zu konfrontieren, wie sie Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) begründet hat. Anthroposophie hat den Anspruch, okkulte Geschichts- wissenschaft zu sein und damit in Tiefen des Verständnisses einzudringen, wohinein die Schulwissenschaft nicht reicht. Folgende Fragen müssen behandelt werden: Was ist eigentlich Geschichte? Wie korrespondiert Geschichte mit dem menschlichen Bewusst- sein im Entwicklungsgang? Die Jungfrau von Orleans, Jeanne Symptom an anderem Ort in Europa, mit eigentlich) bildeten noch auf ihren Kathe- d´Arc (1412-1431), brachte durch ihren dem neue Lebensverhältnisse in die Men- dralen und Kirchen jene Wesenheiten ab, spirituell kämpferischen Einsatz den schen einziehen. Die sog. griechisch-latei- die keiner Phantasie entsprangen, sondern Keim der Unabhängigkeit Frankreichs nische Kulturepoche geht für Steiner, für dem um 1500 bereits weitgehend (Aus- und Englands voneinander. Was die Le- chronologiekritisches Denken bezeich- nahmen gibt es auch hier) erloschenen al- gende von engelhafter Weisung dieses nend, erst im 15. Jahrhundert zu Ende. ten Hellsehen des nordischen Menschen: Auftrages zu berichten weiß, bestätigte Beide den Feuertod erleidenden Neuerer, Greife, Faune, Nixen, Kobolde, Undinen, sich dem hellseherischen Blick Rudolf die Jungfrau wie der Tscheche, markieren Sphinxgestalten usw. Das römische Impe- Steiners, und zwar ohne jede Trübung sei- mit dem beginnenden 15. Jahrhundert die rium, das den christlichen Namen usur- nes Bewusstseins, geschweige denn durch von der geistigen Weltenführung (in etwa pierte, bekämpfte dieses abgelaufene Zeit- Hypnose, Trance oder andere Hilfstech- Hegels Weltgeist entsprechend) beabsich- alter der schauenden germanischen Religi- niken, mit denen heutzutage versucht tigte Entfaltung der „Bewusstseinsseele“ on, denn Ragnarök ist längst gewesen. -

Lehrerrundbrief

LEHRERRUNDBRIEF Inhalt Digitaler Wandel als Gesellschaftssituation – Herausforderungen für Mensch, Gesellschaft und Pädagogik Spiegelungen – Pädagogik und Zeitgeschichte Ist das SSC tatsächlich eine Gegenpraxis? Was ist aktuell Waldorfpädagogik? Evolution – Theorie und Fach an Waldorfschulen »Eine elektrisch geladene Wolke« Lebensbilder LEHRERRUNDBRIEF 107 Buchbesprechungen März 2018 neuPäFoAnzeige_09_2017_Layout 1 03.08.17 13:03 Seite 1 GESTALTEN + ENTDECKEN Deutsch Polaritäten im Dreidimensionalen Immo Diener stellt in diesem Buch einen anderen Ansatz für die Epoche zur Projektiven Individuationswege Geometrie vor, der das räumliche Denkvermögen Band 1 und 2 der Jugendlichen in den Mittelpunkt stellt und zudem die Leserinnen und Leser allgemein dazu Günter Boss anregt, ihr eigenes Denken in Bewegung zu bringen. Seine Epoche ist vielfach erfolgreich erprobt Band 1 und schafft es in einer sehr konzentrierten Wenn die Dichtung aus dem Leben Weise die Dualitätsgesetze an Hexaeder und einen Mythos macht … Oktaeder deutlich zu machen und dann Eine anthropologisch-anthroposo- anzuwenden. Ein Buch für Liebhaberinnen phische Perspektive auf den Lehrplan und Liebhaber der Geometrie – und alle, die es werden wollen. des Deutschunterrichts in der Oberstufe der Waldorfschule Band 2 Unterwegs mit Literatur Vorschläge zum Unterricht während der Ober- Immo Diener: »Projektive Geometrie. Denken in Bewegung« stufenzeit in den »zweiten« Deutsch-Epochen der Pädagogische Forschungsstelle Stuttgart edition waldorf 10. bis 12. Klassen an der Waldorfschule 1. Auflage 2017, 172 Seiten, in Leinen gebunden, Format: 17 x 24 cm ISBN 978-3-944911-45-8 | 29,80 Euro Die beiden Bände enthalten nicht nur für Deutsch lehrer*innen zahlreiche Best.-Nr.: 1661 Anregungen für die klassischen Oberstufenepochen, sondern richten sich an alle, die sich für eine Zusammenschau von Literatur und Fragen des Lebens interessieren. -

Centre Guy Lorge « Eveil En Rencontres »

IDCCH ASBL (Initier, Développer, Connaître, Cultiver, Humaniser) Centre Guy Lorge « Eveil en Rencontres » Librairie associative - Centre de Documentation Rue du Centre, 12 B-4560 Auvelais (Sambreville) Renseignements : +32 (0)494 789 048 Courrier et commandes : [email protected] https://www.idcch.be Date : 01/08/2019 Page 2 Guy Lorge Aussi accessible à nos membres 2ème édition en prêt du livre mai 2014 dans notre centre de documentation ô homme, connais-toi toi-même et deviens toi-même ! exhortation que l'homme s'adresse à lui-même 17,00 € dans éveil en rencontres notre librairie Le livre: I D C C H — CENTRE GUY LORGE Page 3 L'auteur: Page 4 PRINTEMPS 1981 - TRIADES 29 N°3 - Indisponible ÉTÉ 1981 - TRIADES 29 N°4 Indisponible I D C C H — CENTRE GUY LORGE Page 5 AUTOMNE 1981 - TRIADES 29 N°1 Bideau : Rudolf Steiner: », Burlotte : HIVER 1981 - TRIADES 29 N°2 Rudolf Steiner: Johannes Hemleben : Paul-Henri Bideau : Pierre Feschotte : Michel Joseph: S. Rihouêt-Coroze : Page 6 PRINTEMPS 1982 - TRIADES 30 N°3 Rudolf Steiner : Georg Kùhlewind : Dr Joachim Berron : Raymond Burlotte : Isabelle Burlotte : Claude Latars : ? ÉTÉ 1982 - TRIADES 30 N°4 Rudolf Steiner: Paul-Henri Bideau : Athys Floride: Michel Joseph : Marguerite Rédiger: Henriette Bideau : Manfred Krüger: Patrick Sirdey : Athys Floride: I D C C H — CENTRE GUY LORGE Page 7 AUTOMNE 1982 - TRIADES 30 N°1 edwig Greiner-Vogel: I'égoïté Raymond Burlotte: Athys Floride: HIVER 1982 - TRIADES 30 N°2 Rudolf Steiner: Hedwig Greiner-Vogel : Otto Julius Hartmann : Ernst-M icliael Kran ich : Dr Victor Bott : Page 8 PRINTEMPS 1983 - TRIADES 31 N°3 Rudolf Steiner: Christianisme et anti-christianisme à notre époque Hedwig Greiner-Vogel : La crise mortelle de Faust et le message de Pâques François Jordan: Clairvoyance du passé, clairvoyance de notre temps Jôrgen Smit: L'événement de l'apparition du Christ dans le monde éthérique Henriette Bideau : Christianisme» et publicité . -

Le Dynamot Des Nouvelles Fraîches De Votre Association PRINTEMPS/ÉTÉ 2015 L E S O L E I L D E L ’E S P R I T a F F I R M E

Le Dynamot Des nouvelles fraîches de votre Association PRINTEMPS/ÉTÉ 2015 L e s o l e i l d e l ’e s p r i t a f f i r m e s a v i c t o i r e ! DL Quel est donc le système de forces qui intègre harmonieusement l’homme à l’être vivant de la terre? L’observation directe nous montre que ce ne peut être que la lumière. Tout homme à l’esprit non prévenu ressent comme formant la base de la vie ses effets vivifiants, réchauffants, rafraîchissants, qui égayent et affermissent le cœur et l’esprit. La lumière crée déjà les fondements communs de l’existence par le rythme des jours et des saisons, et aussi par la nourriture et le climat. On peut voir ici déjà que la lumière est d’une importance fondamentale non seulement pour le monde végétal, mais aussi pour l’humanité. (Médecine à l’image de l’homme, Tome 1, Husemann et Wolff) Suite page 32 etc. Le pouvoir créateur de la lumière solaire! Page 1 Lettre de l’éditeure les clés de nos pa- tins à roulettes qu’on chaussait sans tar- Dans mon cœur jaillit la force du soleil der sur nos bottes de caoutchouc dès que Par Danièle Laberge les trottoirs appa- raissaient. La corde «Le rayon de soleil à danser, les bolos Scintillant de lumière et les yoyos retrou- A glissé sur la terre.» vaient rapidement leur place d’honneur (Solstices et équinoxes, Steiner) dans la cour de la petite école. -

Goldenblade 2002.Pdf

RUDOLF STEINER LIBRARY VYDZ023789 T H E G O L D E N B L A D E KINDLING SPIRIT 2002 54th ISSUE RUDOLF STEINER LIBRARY 65 FERN HILL RD GHENT NY 12075 KINDLING SPIRIT Edited by William Forward, Simon Blaxland-de Lange and Warren Ashe The Golden Blade Anthroposophy springs from the work and teaching of Rudolf Steiner. He described it as a path of knowledge, to guide the spiritual in the human being to the spiritual in the universe. The aim of this annual journal is to bring the outlook of anthroposophy to bear on questions and activities relevant to the present, in a way which may have lasting value. It was founded in 1949 by Charles Davy and Arnold Freeman, who were its first editors. The title derives from an old Persian legend, according to which King Jamshid received from his god, Ahura Mazda, a golden blade with which to fulfil his mission on earth. It carried the heavenly forces of light into the darkness of earthly substance, thus allowing its transformation. The legend points to the pos sibility that humanity, through wise and compassionate work with the earth, can one day regain on a new level what was lost when the Age of Gold was supplanted by those of Silver, Bronze and Iron. Technology could serve this aim; instead of endan gering our plantet's life, it could help to make the earth a new sun. Contents First published in 2001 by The Golden Blade © 2001 The Golden Blade Editorial Notes 7 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission of The Human Being's Responsibility for the Evolution -

Viktor Ullmann's Steffen-Lieder Op.17

UPTON, RADHA, D.M.A. Between Heaven and Earth: Viktor Ullmann‟s Steffen-Lieder Op.17. (2011) Directed by Dr. Andrew Harley. 92 pp. The life and the work of Austrian composer, conductor, pianist, and musical essayist Viktor Ullmann (1898-1944) were for many years largely lost to history. One factor that may well have contributed to this situation was that, being Jewish, he was among those who were persecuted and killed under the National Socialist regime during the Second World War. Only the persistent work of musicologists, mainly within the last twenty to thirty years, has been able to shed some light on the circumstances of his life. While much research has been done regarding Ullmann‟s life, the body of research focusing on his works is still fairly small. Ullmann‟s Lieder, in particular, have not been discussed to their full extent. The growing availability of his Lieder in print and on audio recordings expands the possibilities for further research. The present study discusses Ullmann‟s Sechs Lieder Op. 17 (1937), settings of poetry by the Swiss anthroposophic poet Albert Steffen (1884-1963). First, the paper familiarizes the reader with general aspects of Ullmann‟s life and work, his holistic Weltanschauung Anthroposophy, and his musical ideals. Second, it provides an overview of his Lieder, including his general knowledge and assessment of the human voice. Finally, after a brief introduction to both life and work of the poet, the study provides an interpretative analysis of the Steffen-Lieder in terms of Ullmann‟s musical language and his response to the poetry. -

Training Concept for Metal Colour Light Therapist

Training concept for metal colour light therapist Lichtblick e.V., Schwörstadt (D) in cooperation with: Filderklinik, Filderstadt-Bonlanden (D) Blackthorn Medical Centre, Maidstone (GB) Helios Medical Centre, Bristol (GB) Vidar-Kliniken, Järna (S) Therapeuticum Raphaelhaus, Stuttgart (D) Lebensgemeinschaft Bingenheim e.V., Echzell (D) Helios Center for Therapeutic Arts, Carbondale, Colorado (USA) Private Practice for Art Therapy, Standish, Maine (USA) Gold Purpur - Lichtblick, Marianne Altmaier The original training concept from Marianne Altmaier will be at the basis of this training course. The colleagues of Lichtblick e.V., the trained Metal Colour Light Therapists at their working places and external docents will do the training. Modifications of training modules will be reserved for us. Schwörstadt, November 2017 Friedlinde Meier and Lucien Turci Concept The use of Metal Colour Light Therapy requires a sound education. The concept is orientated through 14 years of clinical and remedial educational experiences with the application of Metal Colour Light glasses as well as the qualitative and quantitative results of research for effects of this new therapy form. The training will take place at atelier where the colour light glasses are made and in those locations where they are applied therapeutically. Hence the training is mobile. Conditions The training is an additional one provided for: Anthroposophic therapists like art, music, curative eurythmy, doctors, natural doctors and remedial educators. Period of training Beginn: in August 2018 about 3 years in 3 Sessions in each case. 1st Session of every training year will last 7 days and takes place in LIchtblick e.V. Schwörstadt, Germany, in working places for making and engraving glass and in the room for Metal Colour Light Therapy. -

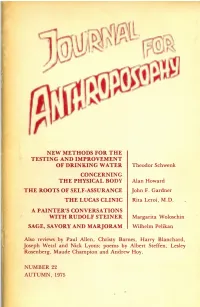

Journal Fnthpsy N Ew Methods for the Testing

JOURNAL FORANTHROPOSOPHYNEW METHODS FOR THE TESTING AND IMPROVEMENT OF DRINKING WATER Theodor Schwenk CONCERNING THE PHYSICAL BODY Alan Howard THE ROOTS OF SELF-ASSURANCE John F. Gardner THE LUCAS CLINIC Rita Leroi, M.D. A PAINTER S CONVERSATIONS WITH RUDOLF STEINER Margarita Woloschin SAGE, SAVORY AND MARJORAM Wilhelm Pelikan Also reviews by Paul Allen, Christy Barnes, Harry Blanchard, Joseph Wetzl and Nick Lyons; poems by Albert Steffen, Lesley Rosenberg, Maude Champion and Andrew Hoy. NUMBER 22 AUTUMN, 1975 Spiritual knowledge is the nourishment of the spirit. By withholding it, man lets his spirit starve and perish; thus enfeebled he grows powerless against processes in his physical and life bodies which gain the upper hand and overpower him. Rudolf Steiner Journal for Anthroposophy. Number 22, Autumn, 1975 © 1975 The Anthroposophical Society in America, Inc. New Methods for the Testing and Improvement of Drinking Water THEODOR SCHWENK Many of those who live in our great cities no longer drink the water from their faucets but prefer to buy expensive mineral water and bottled spring water. Whereas formerly it was taken for granted that people drew drinking water from a spring or well, where it begins its cycle, nowadays, for the most part, we must resort to treating polluted river water so as to make it chemically and bacterio- logically “acceptable.” This, however, ignores the fact that drinking water consists not only of the chemical element H2O — albeit with various salts and trace elements held in solution — but is actually a [Image: photograph]Pattern formed by drinking water of highest quality. 1 [Image: photograph]Pattern formed by a sample of drinkable quality from a Black Forest stream. -

Gesamtinhaltsverzeichnis 1947-1971 Zu "Mitteilungen Aus Der Anthroposophischen Arbeit in Deutschland"

Fünfundzwanzig Jahre Gesamtinhaltsverzeichnis 1947-1971 Mitteilungen aus der anthroposophischen Arbeit in Deutschland Gesamtüberblick über den Inhalt in den Jahren 1947-1971 Zusammengestellt von Herta Blume Nur für Mitglieder der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Seite Vorbemerkung Geleitwort III Die Redaktionen der Mitteilungen IV Motive aus dem Jahre 1923 V 1. Aufsätze - Erinnerungen - Zuschriften A. Nach Sachgebieten chronologisch geordnet Arbeit an der anthroposophischen Substanz 1 Erkenntnis- und Schulungs weg 6 Die Weihnachtstagung und der Grundstein 7 Gesellschaftsgestaltung - Gesellschaftsgeschichte 9 Völkerfragen, insbesondere Mittel- und Osteuropa 12 Die soziale Frage - Soziale Dreigliederung 14 Waldorfschul-Pädagogik 18 Medizin - Heilpädagogik 19 Naturwissenschaft - Technik 20 Ernährung - Landwirtschaft 22 Elementarwesen 23 Kalender - Ostertermin - kosmische Aspekte 24 Jahreslauf - Jahresfeste - Erzengel 25 Der Seelenkalender 27 Zum Spruchgut von Rudolf Steiner 27 Eurythmie - Sprache - Dichtung 29 Über die Leier 29 Bildende Kunst - Kunst im Allgemeinen 30 Die Mysteriendramen 31 Die Oberuferer Weihnachtsspiele 32 Über Marionettenspiele 32 Baukunst - Der Bau in Dornach 33 Die Persönlichkeit Rudolf Steiners, ihr Wesen und Wirken 35 Marie Steiner-von Sivers 38 Erinnerungen an Persönlichkeiten und Ereignisse 39 Biographisches und Autobiographisches 43 Seite Christian Rosenkreutz 44 Goethe 44 Gegnerfragen 45 Genußmittel - Zivilisationsschäden 46 Verschiedenes 47 B. Nach Autoren geordnet 49 Ir. Buchbesprechungen A.