Lives and Legacy by Joyce Nao Takahashi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Immigration History

CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) By HOSOK O Bachelor of Arts in History Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 2000 Master of Arts in History University of Central Oklahoma Edmond, Oklahoma 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2010 © 2010, Hosok O ii CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) Dissertation Approved: Dr. Ronald A. Petrin Dissertation Adviser Dr. Michael F. Logan Dr. Yonglin Jiang Dr. R. Michael Bracy Dr. Jean Van Delinder Dr. Mark E. Payton Dean of the Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For the completion of my dissertation, I would like to express my earnest appreciation to my advisor and mentor, Dr. Ronald A. Petrin for his dedicated supervision, encouragement, and great friendship. I would have been next to impossible to write this dissertation without Dr. Petrin’s continuous support and intellectual guidance. My sincere appreciation extends to my other committee members Dr. Michael Bracy, Dr. Michael F. Logan, and Dr. Yonglin Jiang, whose intelligent guidance, wholehearted encouragement, and friendship are invaluable. I also would like to make a special reference to Dr. Jean Van Delinder from the Department of Sociology who gave me inspiration for the immigration study. Furthermore, I would like to give my sincere appreciation to Dr. Xiaobing Li for his thorough assistance, encouragement, and friendship since the day I started working on my MA degree to the completion of my doctoral dissertation. -

Amache Teacher Resource Guide-Secondary

Annotated Resource Set (ARS) Amache Teacher Resource Guide-Secondary Title/Content Area: Amache /US History Developed by: Kelly Jones-Wagy Grade Level: 9-12 Contextual Paragraph During World War II, 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans were forced into internment camps—including one in southeastern Colorado called the Granada Relocation Center, or “Amache.” Camp Amache was one of ten War Relocation Authority, or internment, camps where US authorities forced Japanese Americans to live after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Home to nearly 7,300 internees from 1942 to 1945, Amache now is a National Historic Landmark. Governor Ralph L. Carr took an unpopular stance, inviting Japanese Americans to stay in Colorado after the war and publicly stating his opinion that internment was unconstitutional. Amache officially closed in October 1945 following the end of World War II. However, for many of the Japanese internees, there was no home to return to. Some chose to stay in Colorado, as they were welcomed by Governor Carr. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, awarding $20,000 to every surviving internee and essentially apologizing for the internment process. 1 Resource Set Title Letter from Governor Letter from Robert D. Executive Order 9066 Map of Concentration Battle Honors for the Ralph Carr to Mrs. J.A. Elder to Governor Camps 442nd Hughes Ralph Carr Description March 6, 1942‐ March 1, 1942‐State February 19, 1942‐ Map shows where the Two letters from Governor Carr Senator Robert Elder President Roosevelt 10 relocation centers generals in 1945 responds to a woman requests that the uses executive power were located in the outlining the in La Junta who is governor refuse to to confine people of United States, their distinguished concerned that the allow the Japanese Japanese descent for populations, and the performance and internment camp is into Colorado and the duration of the type of each center. -

Utah Curriculum Units* * Download Other Enduring Community Units (Accessed September 3, 2009)

ENDURING COMMUNITIES Utah Curriculum Units* * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). Gift of the Nickerson Family, Japanese American National Museum (97.51.3) All requests to publish or reproduce images in this collection must be submitted to the Hirasaki National Resource Center at the Japanese American National Museum. More information is available at http://www.janm.org/nrc/. 369 East First Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 | Fax 213.625.1770 | janm.org | janmstore.com For project information, http://www.janm.org/projects/ec Enduring Communities Utah Curriculum Writing Team RaDon Andersen Jennifer Baker David Brimhall Jade Crown Sandra Early Shanna Futral Linda Oda Dave Seiter Photo by Motonobu Koizumi Project Managers Allyson Nakamoto Jane Nakasako Cheryl Toyama Enduring Communities is a partnership between the Japanese American National Museum, educators, community members, and five anchor institutions: Arizona State University’s Asian Pacific American Studies Program University of Colorado, Boulder University of New Mexico UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures Davis School District, Utah 369 East First Street Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 Fax 213.625.1770 janm.org | janmstore.com Copyright © 2009 Japanese American National Museum UTAH Table of Contents 4 Project Overview of Enduring Communities: The Japanese American Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah Curricular Units* 5 Introduction to the Curricular Units 6 Topaz (Grade 4, 5, 6) Resources and References 34 Terminology and the Japanese American Experience 35 United States Confinement Sites for Japanese Americans During World War II 36 Japanese Americans in the Interior West: A Regional Perspective on the Enduring Nikkei Historical Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Utah (and Beyond) 60 State Overview Essay and Timeline 66 Selected Bibliography Appendix 78 Project Teams 79 Acknowledgments 80 Project Supporters * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). -

The Voices of Children: Re-Imagining the Internment of Japanese Americans Through Poetry

Social Studies and the Young Learner 25 (4), pp. 30–32 ©2013 National Council for the Social Studies The Voices of Children: Re-imagining the Internment of Japanese Americans through Poetry Elizabeth M. Frye and Lisa A. Hash In this article, we describe just one activity from an interdisciplinary social justice unit1 taught to two fifth-grade social studies classes with the use of Cynthia Kadohata’s multicultural historical fiction novel Weedflower.2 Often, our younger students feel their voices are silenced...their messages are not heard. Like many of our fifth-grade students, the main characters in Kadohata’s novel are marginalized peoples whose voices were kept silent during a time of war hysteria. In this historical novel, Sumiko, a young Japanese American girl and her family are forced to relocate to Poston Internment Camp after the attacks on Pearl Harbor. Poston, located in southwestern Arizona, was the largest of the ten internment camps (or “prison camps,” as many of its former residents called it) operated by the U.S. government during World War II. While at Poston, Sumiko befriends Frank, a young Mojave Indian who lives on the neighboring reservation. The Constitution’s Promises and Principles American was ever found guilty of endangering the U.S. during While learning about the internment camps, students also learn World War II. (Indeed, President Roosevelt recognized that the about the U.S. Constitution—how its promises were first violated, then-territory of Hawaii would collapse without its business and then, many years later, partially redeemed. leaders, administrators, engineers, and other civil servants—most The Fifth Amendment to the Constitution states, of whom were of Japanese American descent. -

Resources Available from Twin Cities JACL

CLASSROOM RESOURCES ON WORLD WAR II HISTORY AND THE JAPANESE AMERICAN EXPERIENCE Available from the Twin Cities chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) (Updated September 2013) *Denotes new to our collection Contact: Sally Sudo, Twin Cities JACL, at [email protected] or (952) 835-7374 (days and evenings) SPEAKERS BUREAU Topics: Internment camps and Japanese American WWII soldiers Volunteer speakers are available to share with students their first-hand experiences in the internment camps and/or as Japanese American soldiers serving in the U.S. Army in the European or Pacific Theaters during World War II. (Note: limited to schools within the Twin Cities metropolitan area.) LIST OF RESOURCES Materials are available on loan for no charge Videocassette Tapes Beyond Barbed Wire - 88 min 1997, Mac and Ava Picture Productions, Monterey, CA Documentary. Personal accounts of the struggles that Japanese Americans faced when they volunteered or were drafted to fight in the U.S. Armed Forces during World War II while their families were interned in American concentration camps. The Bracelet - 25 min 2001, UCLA Asian American Studies Center and the Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA Book on video. Presentation of the children’s book by Yoshiko Uchida about two friends separated by war. Second grader Emi is forced to move into an American concentration camp, and in the process she loses a treasured farewell gift from her best friend. Book illustrations are interwoven with rare home movie footage and historic photographs. Following the reading, a veteran teacher conducts a discussion and activities with a second grade class. -

Collection Highlights Since Its Founding in 1924, the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts Has Built a Collection of Nearly 5,000 Artworks

Collection Highlights Since its founding in 1924, the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts has built a collection of nearly 5,000 artworks. Enjoy an in-depth exploration of a selection of those artworks acquired by gift, bequest, or purchase support by special donors, as written by staff curators and guest editors over the years. Table of Contents KENOJUAK ASHEVAK Kenojuak Ashevak (ken-OH-jew-ack ASH-uh-vac), one of the most well-known Inuit artists, was a pioneering force in modern Inuit art. Ashevak grew up in a semi-nomadic hunting family and made art in various forms in her youth. However, in the 1950s, she began creating prints. In 1964, Ashevak was the subject of the Oscar-nominated documentary, Eskimo* Artist: Kenojuak, which brought her and her artwork to Canada’s—and the world’s—attention. Ashevak was also one of the most successful members of the Kinngait Co-operative, also known as the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, established in 1959 by James Houston, a Canadian artist and arts administrator, and Kananginak Pootoogook (ka-nang-uh-nak poo-to-guk), an Inuit artist. The purpose of the co-operative is the same as when it was founded—to raise awareness of Inuit art and ensure indigenous artists are compensated appropriately for their work in the Canadian (and global) art market. Ashevak’s signature style typically featured a single animal on a white background. Inspired by the local flora and fauna of the Arctic, Ashevak used bold colors to create dynamic, abstract, and stylized images that are devoid of a setting or fine details. -

November 5, 2009

ATTACHMENT 2 L ANDMARKSLPC 01-07-10 Page 1 of 18 P RESERVATION C OMMISSION Notice of Decision MEETING OF: November 5, 2009 Property Address: 2525 Telegraph Avenue (2512-16 Regent Street) APN: 055-1839-005 Also Known As: Needham/Obata Building Action: Landmark Designation Application Number: LM #09-40000004 Designation Author(s): Donna Graves with Anny Su, John S. English, and Steve Finacom WHEREAS, the proposed landmarking of 2525 Telegraph Avenue, the Needham/Obata Building, was initiated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission at its meeting on February 5, 2009; and WHEREAS, the proposed landmarking of the Needham/Obata Building is exempt from CEQA pursuant to Section 15061.b.3 (activities that can be seen with certainty to have no significant effect on the environment) of the CEQA Guidelines; and WHEREAS, the Landmarks Preservation Commission opened a public hearing on said proposed landmarking on April 2, 2009, and continued the hearing to May 7, 2009, and then to June 4, 2009; and WHEREAS, during the overall public hearing the Landmarks Preservation Commission took public testimony on the proposed landmarking; and WHEREAS, on June 4, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission determined that the subject property is worthy of Landmark status; and WHEREAS, on July 9, 2009, following release of the Notice of Decision (NOD) on June 29, 2009, the property owner Ali Elsami submitted an appeal requesting that the City Council overturn or remand the Landmark decision; and WHEREAS, on September 22, 2009, the City Council considered Staff’s -

Download the Entire Journey Home Curriculum

Life Interrupted: The Japanese American Experience in WWII Arkansas Journey Home Curriculum An interdisciplinary unit for 4th-6th grade students View of the Jerome Relocation Center as seen from the nearby train tracks, June 18, 1944. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration, ARC ID 539643, Photographer Charles Mace Kristin Dutcher Mann, Compiler and Editor Ryan Parson, Editor Vicki Gonterman Patricia Luzzi Susan Turner Purvis © 2004, Board of Trustees, University of Arkansas 2 ♦ Life Interrupted: Journey Home Life Interrupted: The Japanese American Experience in World War II Arkansas Life Interrupted is a partnership between the University of Arkansas at Little Rock Public History program and the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, Cali- fornia. Our mission is to research the experiences of Japanese Americans in World War II Arkansas and educate the citizens of Arkansas and the nation about the two camps at Jerome and Rohwer. Major funding for Life Interrupted was provided by the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation. We share the story of Japanese Americans because we honor our nation’s diversity. We believe in the importance of remembering our history to better guard against the prejudice that threatens liberty and equality in a democratic society. We strive as a metropolitan univer- sity and a world-class museum and to provide a voice for Japanese Americans and a forum that enables all people to explore their own heritage and culture. We promote continual exploration of the meaning and value of ethnicity in our country through programs that preserve individual dignity, strengthen our communities, and increase respect among all people. -

Education in Japanese-American Internment Camps, 1942-1945

An Ambitious Social Experiment: Education in Japanese-American Internment Camps, 1942-1945 MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE by OF TECHNOLOGY Christopher Su JUN 0 8 2011 Submitted to the Department of History LIBRARIES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of ARCHIVES Bachelor of Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2011 © 2011 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Signature of the Author............................. vepartment of History May23, 2011 Certified by.................. Craig Steven Wilder Professor of History Thesis Supervisor Accepted by........................................ Anne E. C. McCants Professor of History MacVicar Fellow Head, History Section, School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1. Introduction: Educational Programs at Relocation Centers and the Japanese- American Internment Chapter 2. Educating "Projectiles of Democracy": Americanization Objectives Under the Community School Models of Primary and Secondary Schools 21 Chapter 3. Camp-Organized Adult Education Programs: A Notable Example of Administration-Internee Collaboration 36 Afterword 53 References 57 CHAPTER 1 Introduction: Educational Programs at Relocation Centers and the Japanese-American Internment We, who are graduating tonight and all fellow nisei and sansei are living proofs that the efforts and struggles of our immigrant parents were not in vain. We represent all their labors, their sweat, their sufferings, their tears, their dreams and prayers in this land. We are all they have lived and worked for. And now, now that we have reached young manhood and womanhood, we must individually prove to them that their toils were not in vain, that their faith in us is justified. Tonight, we are getting more than a diploma. -

A Conversation on Japanese American Incarceration & Its Relevance to Today

CONVERSATION KIT Courtesy of the National Archives Tuesday, May 17, 2016 1:00-2:00 pm EDT, 10:00-11:00 am PDT Smithsonian National Museum of American History Kenneth E. Behring Center IN WORLD WAR II NATIONAL YOUTH SUMMIT JAPANESE AMERICAN INCARCERATION 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I: INTRODUCTION TO THE NATIONAL SUMMIT . 3 Introduction . 3 Program Details . 4 Regional Summit Locations . 4 When, Where, and How to Participate . 4 Join the Conversation . 5 Central Questions . 6 Panelists and Participants . 7 Common Core State Standards . 9 National Standards for History . 10 SECTION II: LANGUAGE . 11 Statement on Terminology . 12 SECTION III: LESSON PLANS . 14 Lesson Plans and Resources on Japanese American Incarceration . 15 Lesson Ideas for Japanese American Incarceration and Modern Parallels . 17 SECTION IV: YOUTH LEADERSHIP AND TAKING ACTION . 18 What Can You Do? . 19 SECTION V: ADDITIONAL RESOURCES . .. 21 NATIONAL YOUTH SUMMIT JAPANESE AMERICAN INCARCERATION 3 SECTION I: INTRODUCTION TO THE NATIONAL SUMMIT Thank you for participating in the Smithsonian’s National Youth Summit on Japanese American Incarceration. This Conversation Kit is designed to provide you with lesson activities and ideas for leading group discussions on the issues surrounding Japanese American incarceration and their relevance today. This kit also provides details on ways to participate in the Summit. The National Youth Summit is a program developed by the National Museum of American History in collaboration with Smithsonian Affiliations. This program is funded by the Smithsonian’s Youth Access Grants. Pamphlet, Division of Armed Forces History, Office of Curatorial Affairs, National Museum of American History Smithsonian Smithsonian National Museum of American History National Museum of American History Kenneth E. -

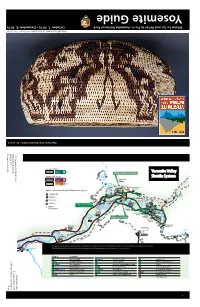

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park October 7, 2015 - December 8, 2015 8, December - 2015 7, October Park National Yosemite in Do to What and Go to Where Butterfly basket made by Julia Parker. Parker. Julia by made basket Butterfly NPS Photo / YOSE 50160 YOSE / Photo NPS Volume 40, Issue 8 Issue 40, Volume America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Summer-only Routes: Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Fall Yosemite Shuttle Village Express Lower Shuttle Yosemite The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System F e E1 5 P2 t i 4 m e 9 Campground os Mirror r Y 3 Uppe 6 10 2 Lake Parking Village Day-use Parking seasonal The Ahwahnee Half Dome Picnic Area 11 P1 1 8836 ft North 2693 m Camp 4 Yosemite E2 Housekeeping Pines Restroom 8 Lodge Lower 7 Chapel Camp Lodge Day-use Parking Pines Walk-In (Open May 22, 2015) Campground LeConte 18 Memorial 12 21 19 Lodge 17 13a 20 14 Swinging Campground Bridge Recreation 13b Reservations Rentals Curry 15 Village Upper Sentinel Village Day-use Parking Pines Beach E7 il Trailhead a r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l E4 Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M ey ses erce all only d R V iver E6 Nevada To & Fall The Valley Visitor Shuttle operates from 7 am to 10 pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

An Oral History with KARL YONEDA

CENTER FOR ORAL AND PUBLIC HISTORY CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, FULLERTON Japanese American Oral History Project An Oral History with KARL YONEDA Interviewed By Ronald C. Larson and Arthur A. Hansen On March 3, 1974 OH 1376.2 This is an edited transcription of an interview conducted for the Center for Oral and Public History, sponsored by California State University, Fullerton. The reader should be aware that an oral history document portrays information as recalled by the interviewee. Because of the spontaneous nature of this kind of document, it may contain statements and impressions that are not factual. The Center for Oral and Public History encourages all researchers to listen to the recording while reading the oral history transcription, as some expressions, verbiage, and intent may be lost in the interpretation from audio to written source. Researchers are welcome to utilize short excerpts from this transcription without obtaining permission as long as proper credit is given to the interviewee, the interviewer, and the Center for Oral and Public History. Permission for extensive use of the transcription and related materials, duplication, and/or reproduction can be obtained by contacting the Center for Oral and Public History, California State University, PO Box 6846, Fullerton CA 92834-6846. Email: [email protected] Copyright © 1974 Center for Oral and Public History California State University, Fullerton O.H. 1353.2 CENTER FOR ORAL AND PUBLIC HISTORY CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, FULLERTON NARRATOR: KARL YONEDA INTERVIEWER: Ronald C. Larson and Arthur A. Hansen DATE: March 3, 1974 LOCATION: San Francisco, California PROJECT: Japanese American RL: This is an interview with Karl Yoneda at his home in San Francisco, California, for the Japanese American Oral History Project [Center for Oral and Public History], California State University, Fullerton.