The Tanforan Memorial Project: How Art and History Intersected

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6086 AR Cover R1:17.310 MFAH AR 2015-16 Cover.Rd4.Qxd

μ˙ The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston annual report 2015–2016 MFAH BY THE NUMBERS July 1, 2015–June 30, 2016 • 900,595 visits to the Museum, the Lillie and Hugh Roy Tuition Attendance Revenue $3.2 Other Cullen Sculpture Garden, Bayou Bend Collection and $2.1 5% 3% $7.1 Gardens, Rienzi, and the Glassell School of Art 11% Membership Revenue $2.9 • 112,000 visitors and students reached through learning 5% and interpretation programs on-site and off-site FY 2016 • 37,521 youth visitors ages 18 and under received free Operating Operating Revenues Endowment or discounted access to the MFAH Fund-raising (million) Spending $14.2 $34.0 22% 54% • 42,865 schoolchildren and their chaperones received free tours of the MFAH • 1,020 community engagement programs were presented Total Revenues: $63.5 million • 100 community partners citywide collaborated with the MFAH Exhibitions, Curatorial, and Collections $12.5 Auxiliary • 2,282,725 visits recorded at mfah.org 20% Activities $3.2 5% • 119,465 visits recorded at the new online collections Fund-raising $4.9 module 8% • 197,985 people followed the MFAH on Facebook, FY 2016 Education, Instagram, and Twitter Operating Expenses Libraries, (million) and Visitor Engagment $12.7 • 266,580 unique visitors accessed the Documents 21% of 20th-Century Latin American and Latino Art Website, icaadocs.mfah.org Management Buildings and Grounds and General $13.1 and Security $15.6 21% • 69,373 visitors attended Sculpted in Steel: Art Deco 25% Automobiles and Motorcycles, 1929–1940 Total Expenses: $62 million • 26,434 member -

Oral History Interview with Roy Emerson Stryker, 1963-1965

Oral history interview with Roy Emerson Stryker, 1963-1965 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Roy Stryker on October 17, 1963. The interview took place in Montrose, Colorado, and was conducted by Richard Doud for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview Side 1 RICHARD DOUD: Mr. Stryker, we were discussing Tugwell and the organization of the FSA Photography Project. Would you care to go into a little detail on what Tugwell had in mind with this thing? ROY STRYKER: First, I think I'll have to raise a certain question about your emphasis on the word "Photography Project." During the course of the morning I gave you a copy of my job description. It might be interesting to refer back to it before we get through. RICHARD DOUD: Very well. ROY STRYKER: I was Chief of the Historical Section, in the Division of Information. My job was to collect documents and materials that might have some bearing, later, on the history of the Farm Security Administration. I don't want to say that photography wasn't conceived and thought of by Mr. Tugwell, because my backround -- as we'll have reason to talk about later -- and my work at Columbia was very heavily involved in the visual. -

Collection Highlights Since Its Founding in 1924, the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts Has Built a Collection of Nearly 5,000 Artworks

Collection Highlights Since its founding in 1924, the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts has built a collection of nearly 5,000 artworks. Enjoy an in-depth exploration of a selection of those artworks acquired by gift, bequest, or purchase support by special donors, as written by staff curators and guest editors over the years. Table of Contents KENOJUAK ASHEVAK Kenojuak Ashevak (ken-OH-jew-ack ASH-uh-vac), one of the most well-known Inuit artists, was a pioneering force in modern Inuit art. Ashevak grew up in a semi-nomadic hunting family and made art in various forms in her youth. However, in the 1950s, she began creating prints. In 1964, Ashevak was the subject of the Oscar-nominated documentary, Eskimo* Artist: Kenojuak, which brought her and her artwork to Canada’s—and the world’s—attention. Ashevak was also one of the most successful members of the Kinngait Co-operative, also known as the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, established in 1959 by James Houston, a Canadian artist and arts administrator, and Kananginak Pootoogook (ka-nang-uh-nak poo-to-guk), an Inuit artist. The purpose of the co-operative is the same as when it was founded—to raise awareness of Inuit art and ensure indigenous artists are compensated appropriately for their work in the Canadian (and global) art market. Ashevak’s signature style typically featured a single animal on a white background. Inspired by the local flora and fauna of the Arctic, Ashevak used bold colors to create dynamic, abstract, and stylized images that are devoid of a setting or fine details. -

View / Open Kiehn 2007 Final.Pdf

Dcscr-1 Canvas: 1\n as Commentary at the Tanforan and Topa; Art Schools of1h1.· Japa11cs1.' \111L·ru.:a11 I ntcrnml'nt. I 9--t:?.d.J5 Katharine Kiehn Clark I lonors Colkgc Thesis :Vla_jor: Art 1 listory Primary Ad\ isor: Prol"essor Mondloch Spring 2007 ii Abstract: The Japanese American Internment occurred in the United States from 1942-45, after Japan's First Air Fleet's bombing of Pearl Harbor. President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which ordered Japanese Americans to be evicted from their homes and re located to the desert forpurposes of national security. While there is much documented research on the historical event, there is little on the visual art that Japanese Americans produced during their confinement. This art, when previously looked at, was used to supplement documentation on the internment, and not appreciated in its own right. This paper looks at this art froman art historical perspective, ascribing equal importance to the art, the artists, and the social/historical context. The art shows a process of shaping a new identity, as Japanese Americans were caught between two cultures in a time of war. Some of the art is characterized by the use of traditional Japanese techniques, and other pieces incorporate more contemporary American styles. The art was also used as a vehicle for social commentary and personal expression during this confusing, lonely,and isolating time period. However, the art fromthe camps was produced by many professionaland established artists of the Japanese American community, and can stand on its own as fine art. This paper looks at the work of fourof these artists: Chiura Obata, Masusaboro and Hisako Hibi, and Mine Okubo. -

November 5, 2009

ATTACHMENT 2 L ANDMARKSLPC 01-07-10 Page 1 of 18 P RESERVATION C OMMISSION Notice of Decision MEETING OF: November 5, 2009 Property Address: 2525 Telegraph Avenue (2512-16 Regent Street) APN: 055-1839-005 Also Known As: Needham/Obata Building Action: Landmark Designation Application Number: LM #09-40000004 Designation Author(s): Donna Graves with Anny Su, John S. English, and Steve Finacom WHEREAS, the proposed landmarking of 2525 Telegraph Avenue, the Needham/Obata Building, was initiated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission at its meeting on February 5, 2009; and WHEREAS, the proposed landmarking of the Needham/Obata Building is exempt from CEQA pursuant to Section 15061.b.3 (activities that can be seen with certainty to have no significant effect on the environment) of the CEQA Guidelines; and WHEREAS, the Landmarks Preservation Commission opened a public hearing on said proposed landmarking on April 2, 2009, and continued the hearing to May 7, 2009, and then to June 4, 2009; and WHEREAS, during the overall public hearing the Landmarks Preservation Commission took public testimony on the proposed landmarking; and WHEREAS, on June 4, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission determined that the subject property is worthy of Landmark status; and WHEREAS, on July 9, 2009, following release of the Notice of Decision (NOD) on June 29, 2009, the property owner Ali Elsami submitted an appeal requesting that the City Council overturn or remand the Landmark decision; and WHEREAS, on September 22, 2009, the City Council considered Staff’s -

2000 Foot Problems at Harris Seminar, Nov

CALIFORNIA THOROUGHBRED Adios Bill Silic—Mar. 79 sold at Keeneland, Oct—13 Adkins, Kirk—Nov. 20p; demonstrated new techniques for Anson, Ron & Susie—owners of Peach Flat, Jul. 39 2000 foot problems at Harris seminar, Nov. 21 Answer Do S.—won by Full Moon Madness, Jul. 40 JANUARY TO DECEMBER Admirably—Feb. 102p Answer Do—Jul. 20; 3rd place finisher in 1990 Cal Cup Admise (Fr)—Sep. 18 Sprint, Oct. 24; won 1992 Cal Cup Sprint, Oct. 24 Advance Deposit Wagering—May. 1 Anthony, John Ed—Jul. 9 ABBREVIATIONS Affectionately—Apr. 19 Antonsen, Per—co-owner stakes winner Rebuild Trust, Jun. AHC—American Horse Council Affirmed H.—won by Tiznow, Aug. 26 30; trainer at Harris Farms, Dec. 22; cmt. on early training ARCI—Association of Racing Commissioners International Affirmed—Jan. 19; Laffit Pincay Jr.’s favorite horse & winner of Tiznow, Dec. 22 BC—Breeders’ Cup of ’79 Hollywood Gold Cup, Jan. 12; Jan. 5p; Aug. 17 Apollo—sire of Harvest Girl, Nov. 58 CHRB—California Horse Racing Board African Horse Sickness—Jan. 118 Applebite Farms—stand stallion Distinctive Cat, Sep. 23; cmt—comment Africander—Jan. 34 Oct. 58; Dec. 12 CTBA—California Thoroughbred Breeders Association Aga Khan—bred Khaled in England, Apr. 19 Apreciada—Nov. 28; Nov. 36 CTBF—California Thoroughbred Breeders Foundation Agitate—influential broodmare sire for California, Nov. 14 Aptitude—Jul. 13 CTT—California Thorooughbred Trainers Agnew, Dan—Apr. 9 Arabian Light—1999 Del Mar sale graduate, Jul. 18p; Jul. 20; edit—editorial Ahearn, James—co-author Efficacy of Breeders Award with won Graduation S., Sep. 31; Sep. -

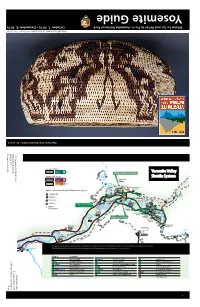

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park October 7, 2015 - December 8, 2015 8, December - 2015 7, October Park National Yosemite in Do to What and Go to Where Butterfly basket made by Julia Parker. Parker. Julia by made basket Butterfly NPS Photo / YOSE 50160 YOSE / Photo NPS Volume 40, Issue 8 Issue 40, Volume America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Summer-only Routes: Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Fall Yosemite Shuttle Village Express Lower Shuttle Yosemite The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System F e E1 5 P2 t i 4 m e 9 Campground os Mirror r Y 3 Uppe 6 10 2 Lake Parking Village Day-use Parking seasonal The Ahwahnee Half Dome Picnic Area 11 P1 1 8836 ft North 2693 m Camp 4 Yosemite E2 Housekeeping Pines Restroom 8 Lodge Lower 7 Chapel Camp Lodge Day-use Parking Pines Walk-In (Open May 22, 2015) Campground LeConte 18 Memorial 12 21 19 Lodge 17 13a 20 14 Swinging Campground Bridge Recreation 13b Reservations Rentals Curry 15 Village Upper Sentinel Village Day-use Parking Pines Beach E7 il Trailhead a r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l E4 Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M ey ses erce all only d R V iver E6 Nevada To & Fall The Valley Visitor Shuttle operates from 7 am to 10 pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

Revised Rules & Guidelines!

REVISED RULES & GUIDELINES! th 5 Annual “Stand in Ansel Adams Footsteps” Juried Competition & Exhibition at The Hudgens Center for Art and Learning The Gwinnett Chapter, Georgia Nature Photographers Association is once again hosting our very successful “Stand in Ansel Adams Footsteps”. This annual competition began as our humble way to pay tribute to the legendry Ansel Adams. It has grown each year with not only more participating photographers, but with the tremendous quality and quantity of the work submitted. BIG IMPROVEMENTS THIS YEAR! This year we are taking it up a Notch! The 5th Annual “Stand in Ansel Adams Footsteps” photographic competition will now for the first time have a 10-week exhibition at The Hudgens Center for Art and Learning. This is to provide recognition to our GNPA members who with their excellent creative work through their effort and skill continue to create wonderful works of art. The exhibit will run from February 15 until April 25, 2020 in The Hudgens Center for Art and Learning, Georgia Galley. What is The Hudgens Center for Art and Learning? Founded over 35 years ago, as the Gwinnett Council for the Arts. Renamed in 2016 as The Hudgens Center for Art and Learning it is a non-profit dedicated to bringing art lovers, leaders, and learners together through quality programs and exhibits. Situated at the south end of the Infinite Energy Center campus with annually more than 13,000 visitors. Presently, the entire Infinite Energy Center campus is undergoing major changes and enhancements. The coveted Hudgens Prize, a $50,000 cash award is one of the largest cash awards given to an individual artist in the entire nation. -

Special September

March 28, 2018 .COM September 9, 2019 SPECIAL SEPTEMBER The Thoroughbreds That Broke Ground In The Air By Joe Nevills There are 20 horses cataloged painted a blue-sky picture of what for this year’s Keeneland Septem- air travel could hold for the future of ber Yearling Sale that were born Thoroughbred racing. overseas and arrived stateside by airplane, and considerably more “This latest way of shipping racers of the auction’s 4,644 entries will will eventually become popular in travel through the sky to destina- that it would enable a horse to tions in different states and different race one afternoon over the New hemispheres after selling to far-flung York tracks and fill his engage- buyers. ment over a Chicago track the next afternoon. The world do When stacked against van and rail move.” travel, which have hauled Thor- oughbreds since the mid-1800s, Everything went to plan except for and transit by ship, which has been the race itself. Wirt G. Bowman was around as long as travelers cross- KEENELAND LIBRARY COLLECTION part of a hot pace in the Spreckles, ing the ocean have needed horses Early air travel but he faded late to finish fifth. in their new destinations, air travel Continued on Page 7 is a relatively new kid on the block. The Wright Brothers first left the ground in Kitty Hawk, N.C. in 1903, and the first Thoroughbred was shipped by plane a quarter-century later. The vanguard for air travel among Thoroughbred racehorses was Wirt G. Bowman, a prized runner from the stable of Cali- fornia hotel and nightclub owner Baron Long. -

A a C P , I N C

A A C P , I N C . Asian Am erican Curriculum Project Dear Friends; AACP remains concerned about the atmosphere of fear that is being created by national and international events. Our mission of reminding others of the past is as important today as it was 37 years ago when we initiated our project. Your words of encouragement sustain our efforts. Over the past year, we have experienced an exciting growth. We are proud of publishing our new book, In Good Conscience: Supporting Japanese Americans During the Internment, by the Northern California MIS Kansha Project and Shizue Seigel. AACP continues to be active in publishing. We have published thirteen books with three additional books now in development. Our website continues to grow by leaps and bounds thanks to the hard work of Leonard Chan and his diligent staff. We introduce at least five books every month and offer them at a special limited time introductory price to our newsletter subscribers. Find us at AsianAmericanBooks.com. AACP, Inc. continues to attend over 30 events annually, assisting non-profit organizations in their fund raising and providing Asian American book services to many educational organizations. Your contributions help us to provide these services. AACP, Inc. continues to be operated by a dedicated staff of volunteers. We invite you to request our catalogs for distribution to your associates, organizations and educational conferences. All you need do is call us at (650) 375-8286, email [email protected] or write to P.O. Box 1587, San Mateo, CA 94401. There is no cost as long as you allow enough time for normal shipping (four to six weeks). -

Farm Security Administation Photographs in Indiana

FARM SECURITY ADMINISTRATION PHOTOGRAPHS IN INDIANA A STUDY GUIDE Roy Stryker Told the FSA Photographers “Show the city people what it is like to live on the farm.” TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 The FSA - OWI Photographic Collection at the Library of Congress 1 Great Depression and Farms 1 Roosevelt and Rural America 2 Creation of the Resettlement Administration 3 Creation of the Farm Security Administration 3 Organization of the FSA 5 Historical Section of the FSA 5 Criticisms of the FSA 8 The Indiana FSA Photographers 10 The Indiana FSA Photographs 13 City and Town 14 Erosion of the Land 16 River Floods 16 Tenant Farmers 18 Wartime Stories 19 New Deal Communities 19 Photographing Indiana Communities 22 Decatur Homesteads 23 Wabash Farms 23 Deshee Farms 24 Ideal of Agrarian Life 26 Faces and Character 27 Women, Work and the Hearth 28 Houses and Farm Buildings 29 Leisure and Relaxation Activities 30 Afro-Americans 30 The Changing Face of Rural America 31 Introduction This study guide is meant to provide an overall history of the Farm Security Administration and its photographic project in Indiana. It also provides background information, which can be used by students as they carry out the curriculum activities. Along with the curriculum resources, the study guide provides a basis for studying the history of the photos taken in Indiana by the FSA photographers. The FSA - OWI Photographic Collection at the Library of Congress The photographs of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) - Office of War Information (OWI) Photograph Collection at the Library of Congress form a large-scale photographic record of American life between 1935 and 1944. -

Published Occasionally by the Friends of the Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley, California 94720

PUBLISHED OCCASIONALLY BY THE FRIENDS OF THE BANCROFT LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 94720 No. 6l May 197s Dr. and Mrs. David Prescott Barrows, with their children, Anna, Ella, Tom, and Betty, at Manila, ig And it is the story of "along the way" that '111 Along the Way comprises this substantial transcript, a gift from her children in honor of Mrs. Hagar's You Have Fun!" seventy-fifth birthday. In her perceptive introduction to Ella Bar From a childhood spent for the most part rows Hagar's Continuing Memoirs: Family, in the Philippines where her father, David Community, University, Marion Sproul Prescott Barrows, served as General Super Goodin notes that the last sentence of this intendent of Education, Ella Barrows came interview, recently completed by Bancroft's to Berkeley in 1910, attended McKinley Regional Oral History Office, ends with the School and Berkeley High School, and en phrase: "all along the way you have fun!" tered the University with its Class of 1919. [1] Life in the small college town in those halcy Annual Meeting: June 1st Bancroft's Contemporary on days before the first World War is vividly recalled, and contrasted with the changes The twenty-eighth Annual Meeting of Poetry Collection brought about by the war and by her father's The Friends of The Bancroft Library will be appointment to the presidency of the Uni held in Wheeler Auditorium on Sunday IN THE SUMMER OF 1965 the University of versity in December, 1919. From her job as afternoon, June 1st, at 2:30 p.m.