Farm Security Administation Photographs in Indiana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View a Printable PDF About IPBS Here

INDIANA PUBLIC BROADCASTING STATIONS Indiana Public Broadcasting Stations (IPBS) is a SERVING HOOSIERS non-profi t corporation comprised of nine NPR radio Through leadership and investment, IPBS stations and eight PBS television stations. It was supports innovation to strengthen public media’s founded on the principle that Indiana’s public media programming and services. It seeks to deepen stations are stronger together than they are apart engagement among Hoosiers and address the and our shared objective is to enrich the lives of rapidly changing ways our society uses media today. Hoosiers every day. IPBS’s priorities are to: IPBS reaches 95% of Indiana’s population • Assist students of all ages with remote through their broadcasts and special events. learning and educational attainment • Aid Indiana’s workforce preparation More than TWO MILLION HOOSIERS consume and readiness IPBS news and programming on a weekly basis. • Expand access to public media content and services in underserved regions IPBS member stations off er local and national • Address Hoosiers’ most pressing health, content. They engage viewers and listeners through social, and economic concerns, including programming, special events and public discussions those brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic that are important to Indiana communities. IPBS • Improve quality of life for all enriches lives by educating children, informing and connecting citizens, celebrating our culture and Programming and Service Areas environment, and instilling the joy of learning. • Government & Politics -

Simone De Beauvoir's Photographic Journey Inspired by Her Diary, America Day by Day

Inspiration / Photography Simone de Beauvoir's photographic journey inspired by her diary, America Day by Day Written by Katy Cowan 22.01.2019 Esher Bubley, Coast to Coast, SONJ, 1947. @ Estate Esther Bubley / Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery / Sous Les Etoiles Gallery This month, Sous Les Etoiles Gallery in New York presents, 1947, Simone de Beauvoir in America, a photographic journey inspired by her diary, America Day by Day published in France in 1948. Curated by Corinne Tapia, director of the Gallery, the show aims to illustrate the depiction of De Beauvoir’s encounter with America at the time. In January of 1947, the French writer and intellectual, Simone de Beauvoir landed in New York’s La Guardia Airport, beginning a four-month journey across America. She travelled from East to the West coast by trains, cars and even Greyhound buses. She has recounted her travels in her personal diary and recorded every experience with minute detail. She stayed 116 days, travelling through 19 states and 56 cities. “The Second Sex”, published in 1949, became a reference in the feminist movement but has certainly masked the talent of diarist Simone de Beauvoir. The careful observer, endowed with a chiselled and precise writing style, travelling was central guidance of the existential experience for her, a woman with infinite curiosity, a thirst for experiencing and discovering everything. In 1929, she made her first trips to Spain, Italy and England with her lifelong partner, the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. In 1947, she made, this time alone, her first trip to the United States, a trip that would have changed her life: "Usually, travelling is an attempt to annex a new object to my universe; this in itself is an undertaking: but today it’s different. -

On Celestial Wings / Edgar D

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Whitcomb. Edgar D. On Celestial Wings / Edgar D. Whitcomb. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. 1. United States. Army Air Forces-History-World War, 1939-1945. 2. Flight navigators- United States-Biography. 3. World War, 1939-1945-Campaigns-Pacific Area. 4. World War, 1939-1945-Personal narratives, American. I. Title. D790.W415 1996 940.54’4973-dc20 95-43048 CIP ISBN 1-58566-003-5 First Printing November 1995 Second Printing June 1998 Third Printing December 1999 Fourth Printing May 2000 Fifth Printing August 2001 Disclaimer This publication was produced in the Department of Defense school environment in the interest of academic freedom and the advancement of national defense-related concepts. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the United States government. This publication has been reviewed by security and policy review authorities and is cleared for public release. Digitize February 2003 from August 2001 Fifth Printing NOTE: Pagination changed. ii This book is dedicated to Charlie Contents Page Disclaimer........................................................................................................................... ii Foreword............................................................................................................................ vi About the author .............................................................................................................. -

Farm Aid: a Case Study of a Charity Rock Organization Andrew Palen University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2016 Farm Aid: a Case Study of a Charity Rock Organization Andrew Palen University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Palen, Andrew, "Farm Aid: a Case Study of a Charity Rock Organization" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1399. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1399 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FARM AID: A CASE STUDY OF A CHARITY ROCK ORGANIZATION by Andrew M. Palen A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee December 2016 ABSTRACT FARM AID: A CASE STUDY ON THE IMPACT OF A CHARITY ROCK ORGANIZATION by Andrew M. Palen The University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor David Pritchard This study examines the impact that the non-profit organization Farm Aid has had on the farming industry, policy, and the concert realm known as charity rock. This study also examines how the organization has maintained its longevity. By conducting an evaluation on Farm Aid and its history, the organization’s messaging and means to communicate, a detailed analysis of the past media coverage on Farm Aid from 1985-2010, and a phone interview with Executive Director Carolyn Mugar, I have determined that Farm Aid’s impact is complex and not clear. -

Mason Williams

City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Mason Williams All Rights Reserved Abstract City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams This dissertation offers a new account of New York City’s politics and government in the 1930s and 1940s. Focusing on the development of the functions and capacities of the municipal state, it examines three sets of interrelated political changes: the triumph of “municipal reform” over the institutions and practices of the Tammany Hall political machine and its outer-borough counterparts; the incorporation of hundreds of thousands of new voters into the electorate and into urban political life more broadly; and the development of an ambitious and capacious public sector—what Joshua Freeman has recently described as a “social democratic polity.” It places these developments within the context of the national New Deal, showing how national officials, responding to the limitations of the American central state, utilized the planning and operational capacities of local governments to meet their own imperatives; and how national initiatives fed back into subnational politics, redrawing the bounds of what was possible in local government as well as altering the strength and orientation of local political organizations. The dissertation thus seeks not only to provide a more robust account of this crucial passage in the political history of America’s largest city, but also to shed new light on the history of the national New Deal—in particular, its relation to the urban social reform movements of the Progressive Era, the long-term effects of short-lived programs such as work relief and price control, and the roles of federalism and localism in New Deal statecraft. -

Tuesday - Saturday, 8:30 A.M

National Archives Southeast Open to the Public: Region Tuesday - Saturday, 8:30 a.m. to 5780 Jonesboro Road 5:00 p.m. Morrow, Georgia 30260 (excluding Federal holidays) 770-968-2100 National Archives and Records Administration SOUTHEAST REGION ARCHIVES 5780 JONESBORO ROAD MORROW, GEORGIA 30260 . www.archives.gov Dear Educator: On behalf of the National Archives and Records Administration - Southeast Region, please accept this copy of the Curriculum Guide for "This Great Nation Will Endure": Photographs ofthe Great Depression. This Curriculum Guide was created by the National Archives Southeast Region with the assistance of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum. The purpose of this guide is to provide materials to help your students gain a better understanding of the difficult conditions Americans faced during the Great Depression along with the government's efforts to stabilize and document the problems. In addition, this guide will familiarize students with the use of primary sources and acquaint them with using document-based historical research techniques. For general information or questions regarding this guide please contact Karen Kopanezos at 770.968.2530. For questions regarding tours of our facilities, please contact Mary Evelyn Tomlin, Southeast Region Public Programs Specialist at 770.968.2555. We hope that this Curriculum Guide will be of assistance to your students. We are grateful for your dedication to education and we look forward to your next visit to the National Archives Southeast Region. Sincerely, James McSweeney -

Hoosiers and the American Story Chapter 3

3 Pioneers and Politics “At this time was the expression first used ‘Root pig, or die.’ We rooted and lived and father said if we could only make a little and lay it out in land while land was only $1.25 an acre we would be making money fast.” — Andrew TenBrook, 1889 The pioneers who settled in Indiana had to work England states. Southerners tended to settle mostly in hard to feed, house, and clothe their families. Every- southern Indiana; the Mid-Atlantic people in central thing had to be built and made from scratch. They Indiana; the New Englanders in the northern regions. had to do as the pioneer Andrew TenBrook describes There were exceptions. Some New Englanders did above, “Root pig, or die.” This phrase, a common one settle in southern Indiana, for example. during the pioneer period, means one must work hard Pioneers filled up Indiana from south to north or suffer the consequences, and in the Indiana wilder- like a glass of water fills from bottom to top. The ness those consequences could be hunger. Luckily, the southerners came first, making homes along the frontier was a place of abundance, the land was rich, Ohio, Whitewater, and Wabash Rivers. By the 1820s the forests and rivers bountiful, and the pioneers people were moving to central Indiana, by the 1830s to knew how to gather nuts, plants, and fruits from the northern regions. The presence of Indians in the north forest; sow and reap crops; and profit when there and more difficult access delayed settlement there. -

Oral History Interview with Roy Emerson Stryker, 1963-1965

Oral history interview with Roy Emerson Stryker, 1963-1965 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Roy Stryker on October 17, 1963. The interview took place in Montrose, Colorado, and was conducted by Richard Doud for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview Side 1 RICHARD DOUD: Mr. Stryker, we were discussing Tugwell and the organization of the FSA Photography Project. Would you care to go into a little detail on what Tugwell had in mind with this thing? ROY STRYKER: First, I think I'll have to raise a certain question about your emphasis on the word "Photography Project." During the course of the morning I gave you a copy of my job description. It might be interesting to refer back to it before we get through. RICHARD DOUD: Very well. ROY STRYKER: I was Chief of the Historical Section, in the Division of Information. My job was to collect documents and materials that might have some bearing, later, on the history of the Farm Security Administration. I don't want to say that photography wasn't conceived and thought of by Mr. Tugwell, because my backround -- as we'll have reason to talk about later -- and my work at Columbia was very heavily involved in the visual. -

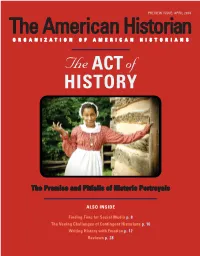

Preview Issue, the American Historian

PREVIEW ISSUE: APRIL 2014 The American Historian ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN HISTORIANS The ACT of HISTORY The Promise and Pitfalls of Historic Portrayals ALSO INSIDE Finding Time for Social Media p. 8 The Vexing Challenges of Contingent Historians p. 10 Writing History with Emotion p. 12 Reviews p. 28 Career and family... We’ve got you covered. Organization of American Historians’ member insurance plans and services have been carefully chosen for their valuable benefits at competitive group rates from a variety of reputable, highly-rated carriers. Professional Home & Auto • Professional Liability • GEICO Automobile Insurance • Private Practice Professional Liability • Homeowners Insurance • Student Educator Professional Liability • Pet Health Insurance Health Life • TIE Health Insurance Exchange • New York Life Group Term • New York Life Group Accidental Death Life Insurance† & Dismemberment Insurance† • New York Life 10 Year Level • Cancer Insurance Plan Group Term Life Insurance† • Medicare Supplement Insurance • Educators Dental Plan † Underwritten by New York Life Insurance Company, New York, NY 10010 Policy Form GMR. Please note: Not all plans are available in all states. Trust for Insuring Educators Administered by Forrest T. Jones & Company (800) 821-7303 • www.ftj.com/OAH Personalized Long Term Care Insurance Evaluation Featuring top insurance companies and special discounts. This advertisement is for informational purposes only and is not meant to define, alter, limit or expand any policy in any way. For a descriptive brochure that summarizes features, costs, eligibility, renewability, limitations and exclusions, call Forrest T. Jones & Company. Arkansas producer license #71740, California producer license #0592939. 2 The American Historian | April 2014 #6608 0314 6608 OAH All Coverage Ad.indd 1 2/26/14 3:46 PM Career and family.. -

1937-1943 Additional Excerpts

Wright State University CORE Scholar Books Authored by Wright State Faculty/Staff 1997 The Celebrative Spirit: 1937-1943 Additional Excerpts Ronald R. Geibert Wright State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/books Part of the Photography Commons Repository Citation Geibert , R. R. (1997). The Celebrative Spirit: 1937-1943 Additional Excerpts. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books Authored by Wright State Faculty/Staff by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Additional excerpts from the 1997 CD-ROM and 1986 exhibition The Celebrative Spirit: 1937-1943 John Collier’s work as a visual anthropologist has roots in his early years growing up in Taos, New Mexico, where his father was head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. His interest in Native Americans of the Southwest would prove to be a source of conflict with his future boss, Roy Stryker, director of the FSA photography project. A westerner from Colorado, Stryker did not consider Indians to be part of the mission of the FSA. Perhaps he worried about perceived encroachment by the FSA on BIA turf. Whatever the reason, the rancor of his complaints when Collier insisted on spending a few extra weeks in the West photographing native villages indicates Stryker may have harbored at least a smattering of the old western anti-Indian attitude. By contrast, Collier’s work with Mexican Americans was a welcome and encouraged addition to the FSA file. -

Henry Wallace Wallace Served Served on On

Papers of HENRY A. WALLACE 1 941-1 945 Accession Numbers: 51~145, 76-23, 77-20 The papers were left at the Commerce Department by Wallace, accessioned by the National Archives and transferred to the Library. This material is ·subject to copyright restrictions under Title 17 of the U.S. Code. Quantity: 41 feet (approximately 82,000 pages) Restrictions : The papers contain material restricted in accordance with Executive Order 12065, and material which _could be used to harass, em barrass or injure living persons has been closed. Related Materials: Papers of Paul Appleby Papers of Mordecai Ezekiel Papers of Gardner Jackson President's Official File President's Personal File President's Secretary's File Papers of Rexford G. Tugwell Henry A. Wallace Papers in the Library of Congress (mi crofi 1m) Henry A. Wallace Papers in University of Iowa (microfilm) '' Copies of the Papers of Henry A. Wallace found at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, the Library of Congress and the University of Iow~ are available on microfilm. An index to the Papers has been published. Pl ease consult the archivist on duty for additional information. I THE UNIVERSITY OF lOWA LIBRAlU ES ' - - ' .·r. .- . -- ........... """"' ': ;. "'l ' i . ,' .l . .·.· :; The Henry A. Wallace Papers :and Related Materials .- - --- · --. ~ '· . -- -- .... - - ·- - ·-- -------- - - Henry A. Walla.ce Papers The principal collection of the papers of (1836-1916), first editor of Wallaces' Farmer; Henry Agard \Vallace is located in the Special his father, H enry Cantwell Wallace ( 1866- Collc:ctions Department of The University of 1924), second editor of the family periodical and Iowa Libraries, Iowa City. \ Val bee was born Secretary of Agriculture ( 1921-192-l:): and his October 7, 1888, on a farm in Adair County, uncle, Daniel Alden Wallace ( 1878-1934), editor Iowa, was graduated from Iowa State University, of- The Farmer, St. -

An All Day Music and Homegrown Festival from Noon to 11 Pm

AN ALL DAY MUSIC AND HOMEGROWN FESTIVAL FROM NOON TO 11 PM. THIS YEAR’S LINEUP INCLUDES: WILLIE NELSON & FAMILY, NEIL YOUNG, JOHN MELLENCAMP, DAVE MATTHEWS AND MORE TO BE ANNOUNCED. About Farm Aid FARM AID IS AMERICA’S LONGEST RUNNING CONCERTFORACAUSE. SINCE 1985, FARM AID CONCERTS HAVE CELEBRATED FAMILY FARMERS AND GOOD FOOD. KEY NUMBERS FOR FARM AID 2017 22k 16 22k Concert Goers Artist Performances People eating HOMEGROWN Concessions® 30 1,903,194,905 HOMEGROWN Media Impressions Village Experiences 3 About Farm Aid CONCERTGOER DEMOGRAPHICS FARM AID 2017 SURVEY Age Group 30% 20% 10% Gender 0% Age 18 -34 Age 35-44 Age 45-54 Age 55-64 Under Age 18 Above Age 65+ 40% Male Household Income 30% 20% 58% Female 10% 0% 150k+ Under $20k 75k - $99.9k $20k - $49.9k $50k - $74.9k 100k - 149.9k 4 About Farm Aid LOYALTY Willingness to Purchase from Farm Aid Sponsors 89% 5 About Farm Aid YOU’RE IN GOOD COMPANY WITH PAST FARM AID SPONSORS 6 About Farm Aid OUR ARTISTS Farm Aid board members Willie Nelson, Neil Young, John Mellencamp and Dave Matthews, joined by more than a dozen artists each year, all generously donate their performances for a full day of music. Farm Aid artists speak up with farmers at the press event on stage just before the concert, attended by 200+ members of the media. Farm Aid artists join farmers throughout the day on the FarmYard stage to discuss food and farming. 7 The Concert Marketing Benefits & Reach FARM AID PROVIDES AN EXCELLENT OPPORTUNITY FOR SPONSORS TO ASSOCIATE WITH ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT MISSIONS IN AMERICA: TO BUILD A VIBRANT, FAMILY FARMCENTERED SYSTEM OF AGRICULTURE AND PROMOTE GOOD FOOD FROM FAMILY FARMS.