Collection Highlights Since Its Founding in 1924, the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts Has Built a Collection of Nearly 5,000 Artworks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2001, Tanglewood

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

2021 Transpacific Yacht Race Event Program

TRANSPACTHE FIFTY-FIRST RACE FROM LOS ANGELES 2021 TO HONOLULU 2 0 21 JULY 13-30, 2021 Comanche: © Sharon Green / Ultimate Sailing COMANCHE Taxi Dancer: © Ronnie Simpson / Ultimate Sailing • Hamachi: © Team Hamachi HAMACHI 2019 FIRST TO FINISH Official race guide - $5.00 2019 OVERALL CORRECTED TIME WINNER P: 808.845.6465 [email protected] F: 808.841.6610 OFFICIAL HANDBOOK OF THE 51ST TRANSPACIFIC YACHT RACE The Transpac 2021 Official Race Handbook is published for the Honolulu Committee of the Transpacific Yacht Club by Roth Communications, 2040 Alewa Drive, Honolulu, HI 96817 USA (808) 595-4124 [email protected] Publisher .............................................Michael J. Roth Roth Communications Editor .............................................. Ray Pendleton, Kim Ickler Contributing Writers .................... Dobbs Davis, Stan Honey, Ray Pendleton Contributing Photographers ...... Sharon Green/ultimatesailingcom, Ronnie Simpson/ultimatesailing.com, Todd Rasmussen, Betsy Crowfoot Senescu/ultimatesailing.com, Walter Cooper/ ultimatesailing.com, Lauren Easley - Leialoha Creative, Joyce Riley, Geri Conser, Emma Deardorff, Rachel Rosales, Phil Uhl, David Livingston, Pam Davis, Brian Farr Designer ........................................ Leslie Johnson Design On the Cover: CONTENTS Taxi Dancer R/P 70 Yabsley/Compton 2019 1st Div. 2 Sleds ET: 8:06:43:22 CT: 08:23:09:26 Schedule of Events . 3 Photo: Ronnie Simpson / ultimatesailing.com Welcome from the Governor of Hawaii . 8 Inset left: Welcome from the Mayor of Honolulu . 9 Comanche Verdier/VPLP 100 Jim Cooney & Samantha Grant Welcome from the Mayor of Long Beach . 9 2019 Barndoor Winner - First to Finish Overall: ET: 5:11:14:05 Welcome from the Transpacific Yacht Club Commodore . 10 Photo: Sharon Green / ultimatesailingcom Welcome from the Honolulu Committee Chair . 10 Inset right: Welcome from the Sponsoring Yacht Clubs . -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Astrophysics in 2006 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5760h9v8 Journal Space Science Reviews, 132(1) ISSN 0038-6308 Authors Trimble, V Aschwanden, MJ Hansen, CJ Publication Date 2007-09-01 DOI 10.1007/s11214-007-9224-0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Space Sci Rev (2007) 132: 1–182 DOI 10.1007/s11214-007-9224-0 Astrophysics in 2006 Virginia Trimble · Markus J. Aschwanden · Carl J. Hansen Received: 11 May 2007 / Accepted: 24 May 2007 / Published online: 23 October 2007 © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2007 Abstract The fastest pulsar and the slowest nova; the oldest galaxies and the youngest stars; the weirdest life forms and the commonest dwarfs; the highest energy particles and the lowest energy photons. These were some of the extremes of Astrophysics 2006. We attempt also to bring you updates on things of which there is currently only one (habitable planets, the Sun, and the Universe) and others of which there are always many, like meteors and molecules, black holes and binaries. Keywords Cosmology: general · Galaxies: general · ISM: general · Stars: general · Sun: general · Planets and satellites: general · Astrobiology · Star clusters · Binary stars · Clusters of galaxies · Gamma-ray bursts · Milky Way · Earth · Active galaxies · Supernovae 1 Introduction Astrophysics in 2006 modifies a long tradition by moving to a new journal, which you hold in your (real or virtual) hands. The fifteen previous articles in the series are referenced oc- casionally as Ap91 to Ap05 below and appeared in volumes 104–118 of Publications of V. -

American Art New York | November 19, 2019

American Art New York | November 19, 2019 AMERICAN ART | 39 2 | BONHAMS AMERICAN ART | 3 American Art at Bonhams New York Jennifer Jacobsen Director Aaron Anderson Los Angeles Scot Levitt Vice President Kathy Wong Specialist San Francisco Aaron Bastian Director American Art New York | Tuesday November 19, 2019 at 4pm BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES ILLUSTRATIONS 580 Madison Avenue +1 (212) 644 9001 Jennifer Jacobsen Front Cover: Lot 15 New York, New York 10022 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax Director Inside Front Cover: Lots 47 and 48 bonhams.com [email protected] +1 (917) 206 1699 Inside Back Cover: Lot 91 [email protected] Back Cover: Lot 14 PREVIEW To bid via the internet please visit Friday, November 15, 10am - 5pm www.bonhams.com/25246 Aaron Anderson Saturday, November 16, 10am - 5pm +1 (917) 206 1616 Sunday, November 17, 12pm - 5pm Please note that bids should be [email protected] Monday, November 18, 10am - 5pm summited no later than 24hrs prior to the sale. New Bidders must REGISTRATION also provide proof of identity when IMPORTANT NOTICE SALE NUMBER: 25246 submitting bids. Failure to do this Please note that all customers, Lots 1 - 101 may result in your bid not being irrespective of any previous processed. activity with Bonhams, are CATALOG: $35 required to complete the Bidder LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS Registration Form in advance of AUCTIONEER AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE the sale. The form can be found Rupert Banner - 1325532-DCA Please email bids.us@bonhams. at the back of every catalogue com with “Live bidding” in the and on our website at www. -

November 5, 2009

ATTACHMENT 2 L ANDMARKSLPC 01-07-10 Page 1 of 18 P RESERVATION C OMMISSION Notice of Decision MEETING OF: November 5, 2009 Property Address: 2525 Telegraph Avenue (2512-16 Regent Street) APN: 055-1839-005 Also Known As: Needham/Obata Building Action: Landmark Designation Application Number: LM #09-40000004 Designation Author(s): Donna Graves with Anny Su, John S. English, and Steve Finacom WHEREAS, the proposed landmarking of 2525 Telegraph Avenue, the Needham/Obata Building, was initiated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission at its meeting on February 5, 2009; and WHEREAS, the proposed landmarking of the Needham/Obata Building is exempt from CEQA pursuant to Section 15061.b.3 (activities that can be seen with certainty to have no significant effect on the environment) of the CEQA Guidelines; and WHEREAS, the Landmarks Preservation Commission opened a public hearing on said proposed landmarking on April 2, 2009, and continued the hearing to May 7, 2009, and then to June 4, 2009; and WHEREAS, during the overall public hearing the Landmarks Preservation Commission took public testimony on the proposed landmarking; and WHEREAS, on June 4, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission determined that the subject property is worthy of Landmark status; and WHEREAS, on July 9, 2009, following release of the Notice of Decision (NOD) on June 29, 2009, the property owner Ali Elsami submitted an appeal requesting that the City Council overturn or remand the Landmark decision; and WHEREAS, on September 22, 2009, the City Council considered Staff’s -

Kaae, Leonard Kuuleinamoku, July 19, 2012 Leonard Kuuleinamoku Kaae, 84, of Honolulu, a Retired Hawaiian Tug & Barge Seaman and an Army Veteran, Died

Kaae, Leonard Kuuleinamoku, July 19, 2012 Leonard Kuuleinamoku Kaae, 84, of Honolulu, a retired Hawaiian Tug & Barge seaman and an Army veteran, died. He was born in Honolulu. He is survived by wife Ruth H. and sisters Ethel Hardley and Rose Giltner. Private services. [Honolulu Star-Advertiser 11 August 2012] Kaahanui, Agnes Lily Kahihiulaokalani, 77, of Honolulu, Hawaii, passed away June 14, 2012 at Kuakini Medical Center. Born July 10, 1934 in Honolulu, Hawaii. She was retired Maintenance Housekeeping Personel at Iolani Palace. She is survived by sons, Clifford Kalani (Marylyn) Kaahanui, Clyde Haumea Kaahanui, Cyrus Kamea Aloha Kaahanui, Hiromi (Jeanette) Fukuzawa; daughters, Katherine Ku’ulei Kaahanui, Kathleen Kuuipo (Arthur) Sing, Karen Kehaulani Kaahanui; 14 grandchildren; 10 great-grandchildren; sister, Rebecca Leimomi Naha. Visitation 10:00 a.m. Thursday (7/19) at Mililani Downtown Mortuary, Funeral Service 11:00 a.m., Burial 2:00 p.m. at Hawaiian Memorial Park Cemetery. Casual Attire. Flowers Welcome. [Honolulu Star-Advertiser 17 July 2012] Kaahanui, Agnes Lily Kahihiulaokalani, June 14, 2012 Agnes Lily Kahihiulaokalani Kaahanui, 77, of Honolulu, a retired Iolani Palace maintenance housekeeping worker, died in Kuakini Medical Center. She was born in Honolulu. She is survived by sons Clifford K., Clyde H. and Cyrus K. Kaahanui, and Hiromi Fukuzawa; daughters Katherine K. and Karen K. Kaahanui, and Kathleen K. Sing; sister Rebecca L. Naha; 14 grandchildren; and 10 great- grandchildren. Visitation: 10 a.m. Thursday at Mililani Downtown Mortuary. Services: 11 a.m. Burial: 2 p.m. at Hawaiian Memorial Park. Casual attire. Flowers welcome. [Honolulu Star- Advertiser 17 July 2012] Kaahanui, Carolyn Luana, July 21, 2012 Carolyn Luana Kaahanui, 59, of Kahului, a Makena Surf housekeeping department employee, died in Maui Memorial Medical Center. -

Picturing France

Picturing France Classroom Guide VISUAL ARTS PHOTOGRAPHY ORIENTATION ART APPRECIATION STUDIO Traveling around France SOCIAL STUDIES Seeing Time and Pl ace Introduction to Color CULTURE / HISTORY PARIS GEOGRAPHY PaintingStyles GOVERNMENT / CIVICS Paris by Night Private Inve stigation LITERATURELANGUAGE / CRITICISM ARTS Casual and Formal Composition Modernizing Paris SPEAKING / WRITING Department Stores FRENCH LANGUAGE Haute Couture FONTAINEBLEAU Focus and Mo vement Painters, Politics, an d Parks MUSIC / DANCENATURAL / DRAMA SCIENCE I y Fontainebleau MATH Into the Forest ATreebyAnyOther Nam e Photograph or Painting, M. Pa scal? ÎLE-DE-FRANCE A Fore st Outing Think L ike a Salon Juror Form Your Own Ava nt-Garde The Flo ating Studio AUVERGNE/ On the River FRANCHE-COMTÉ Stream of Con sciousness Cheese! Mountains of Fra nce Volcanoes in France? NORMANDY “I Cannot Pain tan Angel” Writing en Plein Air Culture Clash Do-It-Yourself Pointillist Painting BRITTANY Comparing Two Studie s Wish You W ere Here Synthétisme Creating a Moo d Celtic Culture PROVENCE Dressing the Part Regional Still Life Color and Emo tion Expressive Marks Color Collectio n Japanese Prin ts Legend o f the Château Noir The Mistral REVIEW Winds Worldwide Poster Puzzle Travelby Clue Picturing France Classroom Guide NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON page ii This Classroom Guide is a component of the Picturing France teaching packet. © 2008 Board of Trustees of the National Gallery of Art, Washington Prepared by the Division of Education, with contributions by Robyn Asleson, Elsa Bénard, Carla Brenner, Sarah Diallo, Rachel Goldberg, Leo Kasun, Amy Lewis, Donna Mann, Marjorie McMahon, Lisa Meyerowitz, Barbara Moore, Rachel Richards, Jennifer Riddell, and Paige Simpson. -

SM a R T M U S E U M O F a R T U N Iv E R S It Y O F C H IC a G O B U L L E T in 2 0 0 6 – 20

http://smartmuseum.uchicago.edu Chicago, Illinois 60637 5550 South Greenwood Avenue SMART SMART M U S EUM OF A RT UN I VER SI TY OFCH ICAG O RT RT A OF EUM S U M SMART 2008 – 2006 N I ET BULL O ICAG H C OF TY SI VER I N U SMART MUSEUM OF ART UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO BULLETIN 2006– 2008 SMART MUSEUM OF ART UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO BULLETIN 2006–2008 MissiON STATEMENT / 1 SMART MUSEUM BOARD OF GOVERNORS / 3 REPORTS FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND DiRECTOR / 4 ACQUisiTIOns / 10 LOANS / 34 EXHIBITIOns / 44 EDUCATION PROGRAMS / 68 SOURCES OF SUPPORT / 88 SMART STAFF / 108 STATEMENT OF OPERATIOns / 112 MissiON STATEMENT As the ar t museum of the Universit y of Chicago, the David and Alfred Smar t Museum of Ar t promotes the understanding of the visual arts and their importance to cultural and intellectual history through direct experiences with original works of art and through an interdisciplinary approach to its collections, exhibitions, publications, and programs. These activities support life-long learning among a range of audiences including the University and the broader community. SMART MUSEUM BOARD OF GOVERNORS Robert Feitler, Chair Lorna C. Ferguson, Vice Chair Elizabeth Helsinger, Vice Chair Richard Gray, Chairman Emeritus Marilynn B. Alsdorf Isaac Goldman Larry Norman* Mrs. Edwin A. Bergman Jack Halpern Brien O’Brien Russell Bowman Neil Harris Brenda Shapiro* Gay-Young Cho Mary J. Harvey* Raymond Smart Susan O’Connor Davis Anthony Hirschel* Joel M. Snyder Robert G. Donnelley Randy L. Holgate John N. Stern Richard Elden William M. Landes Isabel C. -

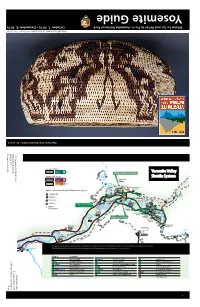

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park October 7, 2015 - December 8, 2015 8, December - 2015 7, October Park National Yosemite in Do to What and Go to Where Butterfly basket made by Julia Parker. Parker. Julia by made basket Butterfly NPS Photo / YOSE 50160 YOSE / Photo NPS Volume 40, Issue 8 Issue 40, Volume America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Summer-only Routes: Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Fall Yosemite Shuttle Village Express Lower Shuttle Yosemite The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System F e E1 5 P2 t i 4 m e 9 Campground os Mirror r Y 3 Uppe 6 10 2 Lake Parking Village Day-use Parking seasonal The Ahwahnee Half Dome Picnic Area 11 P1 1 8836 ft North 2693 m Camp 4 Yosemite E2 Housekeeping Pines Restroom 8 Lodge Lower 7 Chapel Camp Lodge Day-use Parking Pines Walk-In (Open May 22, 2015) Campground LeConte 18 Memorial 12 21 19 Lodge 17 13a 20 14 Swinging Campground Bridge Recreation 13b Reservations Rentals Curry 15 Village Upper Sentinel Village Day-use Parking Pines Beach E7 il Trailhead a r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l E4 Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M ey ses erce all only d R V iver E6 Nevada To & Fall The Valley Visitor Shuttle operates from 7 am to 10 pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

RESEARCHES on CRUSTACEA Special Number 3

OKm iS 7 '"ic^mi n^^ ,',',. y^ ,^^o1»8 RESEARCHES ON CRUSTACEA Special Number 3 The Carcinological Society of Japan 1990 FRONTISPIECE The battle of the Heike and the Genji at Dannoura in 1185. Colored print by Kuniyoshi. RESEARCHES ON CRUSTACEA, SPECIAL NUMBER 3 Crabs of the Subfamily Dorippinae MacLeay, 1838, from the Indo-West Pacific Region (Crustacea: Decapoda: Dorippidae) L. B. Holthuis and Raymond B. Manning The Carcinological Society of Japan Tokyo June 1990 Copyright 1990 by The Carcinological Society of Japan Odawara Carcinological Museum Azabu-Juban 3-11-12, Minatoku, Tokyo 106 Japan Printed by Shimoda Printing, Inc. Matsubase, Shimomashiki-gun Kumamoto 869-05 Japan Issued 30 June 1990 Copies available from the Carcinological Society of Japan Contents Page Introduction 1 Methods 3 Acknowledgments 4 Systematic Account 5 Family Dorippidae MacLeay, 1838 5 Subfamily Dorippinae MacLeay, 1838 5 Key to Indo-West Pacific Genera of Dorippinae 5 Key to Genera of Dorippinae, Based on Male First Pleopods 6 Genus Dorippe Weber, 1795 7 Key to Species of Dorippe 9 Dorippe frascone (Herbst, 1785) 10 Dorippe irrorata Manning and Holthuis, 1986 15 Dorippe quadridens (Fabricius, 1793) 18 Dorippe sinica Chen, 1980 36 Dorippe tenuipes Chen, 1980 43 Genus Dorippoides Serene and Romimohtarto, 1969 47 Key to Species of Dorippoides 49 Dorippoides facchino (Herbst, 1785) 49 Dorippoides nudipes Manning and Holthuis, 1986 66 Heikea, new genus 71 Key to Species of Heikea 72 Heikea arachnoides (Manning and Holthuis, 1986), new combination 72 Heikea japonica -

Chiura Obata (1885-1975)

Chiura Obata (1885-1975) Teacher Packet ©️2020 1 Table of Contents Biography - Chuira Obata 3 Lesson 1 : Obata Inspired Landscape Art (grades K -12) 3 Lesson 2 : Obata-Inspired Poetry (grades 2 - 7) 7 Lesson 3 : Environmentalism “Can Art Save the World?” (grades 4-8) 10 Lesson 4 : 1906 San Francisco Earthquake (grades 4 and above) 13 Lesson 5 : Japanese Incarceration Experience and Political Art (grades 6-12) 18 Resources 22 2 Biography - Chuira Obata Chiura Obata (1885-1975) was a renowned landscape artist, professor, and devoted environmentalist. Born 1885, in Japan, Obata studied ink painting before immigrating to California in 1903. After settling in Japantown in San Francisco, Obata established himself as an artist and took on large-scale commissioned art projects. After an influential trip to Yosemite in 1928, Obata began devoting his art to portraying landscapes and the beauty of nature. Throughout the next decade, Obata continued to earn recognition, but like many Japanese Americans during WWII, his life was violently uprooted as his family was interned, first at Tanforan and then at Topaz. During his imprisonment, Obata was able to start art schools at both camps, teaching hundreds of students and even holding an exhibition in 1942. After the end of the war, Obata returned to lecture at UC Berkeley, joined the Sierra Club’s environmentalist efforts, and consistently celebrated Japanese aesthetics until his death. Over the course of a seven-decade career, Obata became a prominent educator at UC Berkeley and a central leader in -

Large Impact Basins on Mercury: Global Distribution, Characteristics, and Modification History from MESSENGER Orbital Data Caleb I

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 117, E00L08, doi:10.1029/2012JE004154, 2012 Large impact basins on Mercury: Global distribution, characteristics, and modification history from MESSENGER orbital data Caleb I. Fassett,1 James W. Head,2 David M. H. Baker,2 Maria T. Zuber,3 David E. Smith,3,4 Gregory A. Neumann,4 Sean C. Solomon,5,6 Christian Klimczak,5 Robert G. Strom,7 Clark R. Chapman,8 Louise M. Prockter,9 Roger J. Phillips,8 Jürgen Oberst,10 and Frank Preusker10 Received 6 June 2012; revised 31 August 2012; accepted 5 September 2012; published 27 October 2012. [1] The formation of large impact basins (diameter D ≥ 300 km) was an important process in the early geological evolution of Mercury and influenced the planet’s topography, stratigraphy, and crustal structure. We catalog and characterize this basin population on Mercury from global observations by the MESSENGER spacecraft, and we use the new data to evaluate basins suggested on the basis of the Mariner 10 flybys. Forty-six certain or probable impact basins are recognized; a few additional basins that may have been degraded to the point of ambiguity are plausible on the basis of new data but are classified as uncertain. The spatial density of large basins (D ≥ 500 km) on Mercury is lower than that on the Moon. Morphological characteristics of basins on Mercury suggest that on average they are more degraded than lunar basins. These observations are consistent with more efficient modification, degradation, and obliteration of the largest basins on Mercury than on the Moon. This distinction may be a result of differences in the basin formation process (producing fewer rings), relaxation of topography after basin formation (subduing relief), or rates of volcanism (burying basin rings and interiors) during the period of heavy bombardment on Mercury from those on the Moon.