Research Resources at the Smithsonian American Art Museum Amelia A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weaverswaver00stocrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Fiber Arts Oral History Series Kay Sekimachi THE WEAVER'S WEAVER: EXPLORATIONS IN MULTIPLE LAYERS AND THREE-DIMENSIONAL FIBER ART With an Introduction by Signe Mayfield Interviews Conducted by Harriet Nathan in 1993 Copyright 1996 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Kay Sekimachi dated April 16, 1995. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

PUBLIC SCULPTURE LOCATIONS Introduction to the PHOTOGRAPHY: 17 Daniel Portnoy PUBLIC Public Sculpture Collection Sid Hoeltzell SCULPTURE 18

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 VIRGINIO FERRARI RAFAEL CONSUEGRA UNKNOWN ARTIST DALE CHIHULY THERMAN STATOM WILLIAM DICKEY KING JEAN CLAUDE RIGAUD b. 1937, Verona, Italy b. 1941, Havana, Cuba Bust of José Martí, not dated b. 1941, Tacoma, Washington b. 1953, United States b. 1925, Jacksonville, Florida b. 1945, Haiti Lives and works in Chicago, Illinois Lives and works in Miami, Florida bronze Persian and Horn Chandelier, 2005 Creation Ladder, 1992 Lives and works in East Hampton, New York Lives and works in Miami, Florida Unity, not dated Quito, not dated Collection of the University of Miami glass glass on metal base Up There, ca. 1971 Composition in Circumference, ca. 1981 bronze steel and paint Location: Casa Bacardi Collection of the University of Miami Gift of Carol and Richard S. Fine aluminum steel and paint Collection of the University of Miami Collection of the University of Miami Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Camner Location: Gumenick Lobby, Newman Alumni Center Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, Location: Casa Bacardi Location: Casa Bacardi Location: Gumenick Lobby, Newman Alumni Center University of Miami University of Miami Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Blake King, 2004.20 Gift of Dr. Maurice Rich, 2003.14 Location: Wellness Center Location: Pentland Tower 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 JANE WASHBURN LEONARDO NIERMAN RALPH HURST LEONARDO NIERMAN LEOPOLDO RICHTER LINDA HOWARD JOEL PERLMAN b. United States b. 1932, Mexico City, Mexico b. 1918, Decatur, Indiana b. 1932, Mexico City, Mexico b. 1896, Großauheim, Germany b. 1934, Evanston, Illinois b. -

Graphic Recording by Terry Laban of the Global Health Matters Forum on March 25, 2020 Co-Hosted by Craftnow and the Foundation F

Graphic Recording by Terry LaBan of the Global Health Matters Forum on March 25, 2020 Co-Hosted by CraftNOW and the Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research With Gratitude to Our 2020 Contributors* $10,000 + Up to $500 Jane Davis Barbara Adams Drexel University Lenfest Center for Cultural Anonymous Partnerships Jeffrey Berger Patricia and Gordon Fowler Sally Bleznack Philadelphia Cultural Fund Barbara Boroff Poor Richard’s Charitable Trust William Burdick Lisa Roberts and David Seltzer Erik Calvo Fielding Rose Cheney and Howie Wiener $5,000 - $9,999 Rachel Davey Richard Goldberg Clara and Ben Hollander Barbara Harberger Nancy Hays $2,500 - $4,999 Thora Jacobson Brucie and Ed Baumstein Sarah Kaizar Joseph Robert Foundation Beth and Bill Landman Techné of the Philadelphia Museum of Art Tina and Albert Lecoff Ami Lonner $1,000 - $2,499 Brenton McCloskey Josephine Burri Frances Metzman The Center for Art in Wood Jennifer-Navva Milliken and Ron Gardi City of Philadelphia Office of Arts, Culture, and Angela Nadeau the Creative Economy, Greater Philadelphia Karen Peckham Cultural Alliance and Philadelphia Cultural Fund Pentimenti Gallery The Clay Studio Jane Pepper Christina and Craig Copeland Caroline Wishmann and David Rasner James Renwick Alliance Natalia Reyes Jacqueline Lewis Carol Saline and Paul Rathblatt Suzanne Perrault and David Rago Judith Schaechter Rago Auction Ruth and Rick Snyderman Nicholas Selch Carol Klein and Larry Spitz James Terrani Paul Stark Elissa Topol and Lee Osterman Jeffrey Sugerman -

Floating World: the Influence of Japanese Printmaking

Floating World: The Influence of Japanese Printmaking Ando Hiroshige, Uraga in Sagami Province, from the series Harbors of Japan, 1840-42, color woodcut, collection of Ginna Parsons Lagergren Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Poem by Sarumaru Tayû: Soga Hakoômaru, from the series Ogura Imitations of One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets, 1845-48, color woodcut, collection of Jerry & Judith Levy Floating World: The Influence of Japanese Printmaking June 14–August 24, 2013 Floating World explores the influence of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock printmaking on American and European artists from the late 19th century to the present. A selection of Japanese prints sets the stage for Arts & Crafts era works by Charles Bartlett, Elizabeth Colborne, Arthur Wesley Dow, Frances Gearhart, Edna Boies Hopkins, Bertha Lum and Margaret Jordan Patterson. Woodcuts by Helen Franken- thaler illuminate connections between Abstract Expressionism and Japanese art. Prints by Annie Bissett, Kristina Hagman, Ellen Heck, Tracy Lang, Eva Pietzcker and Roger Shimomura illustrate the ongo- ing allure of ukiyo-e as the basis for innovations in printmaking today. In 1891, AmerIcAn ArtisT woodblock prints that depicted the ARThuR WESLEY DOW wrote that “floating world” of leisure and en- “one evening with Hokusai gave me tertainment. Artists began depicting more light on composition and deco- teahouses, festivals, theater and activi- rative effect than years of study of ties like the tea ceremony, flower ar- pictures. I surely ought to compose in an ranging, painting, calligraphy and music. entirely different manner.”1 Dow wrote Landscapes, birds, flowers and scenes of the letter after discovering a book of daily life were also popular. -

Nosferatu (The Undead)

NEWS 500 University Ave., Rochester, NY 14607-1484 585.276.8900 • mag.rochester.edu MAG Contact: Rachael Unger, Director of Marketing and Engagement: 585.276-8934; [email protected] MEMORIAL ART GALLERY PRESENTS NOSFERATU (THE UNDEAD) April 22–June 17, 2018 Rochester, NY, March 5th 2018 — The Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester (MAG) is pleased to announce NOSFERATU (The Undead), a film installation by New York-based artist Javier Téllez that focuses on cinema and mental illness. The work will premiere at MAG on April 22 and remain on view through June 17. NOSFERATU (The Undead) is the first exhibition to be presented as part of “Reflections on Place,” a series of media art commissions inspired by the City of Rochester, New York, and curated by world-renowned authority on the moving image John G. Hanhardt. Téllez’ film was inspired by Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens, the expressionist silent masterpiece directed by F. W. Murnau in 1922. Téllez made the work in collaboration with people living with mental illness after a series of workshops that he conducted on the subjects of vampirism and the representation of psychiatric institutions in film. Combining black-and-white 16mm and color digital film, NOSFERATU (The Undead) was shot at the Eastman Kodak factory, the Dryden Theatre of the George Eastman Museum, and at the Main Street Armory, all in Rochester. “We chose a vampire for the main character of the film,” said Téllez, “because we wanted to reflect on light and darkness as the fundamental principles of -

Art Museum Digital Impact Evaluation Toolkit

Art Museum Digital Impact Evaluation Toolkit Developed by the Cleveland Museum of Art’s Office of Research & Evaluation in collaboration with Rockman et al thanks to a generous grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. 2018 Content INTRODUCTION ..........................................................2 01 VISITOR CONTEXT .....................................................3 Demographics ............................................................4 Motivations ..............................................................5 Visitation Frequency .......................................................6 02 CONTEXT OF THE DIGITAL EXPERIENCE ...................................7 Prior Digital Engagement ................................................... 8 Timing of Interactive Experience ..........................................9 03 VISITORS’ RELATIONSHIP WITH ART .....................................10 04 ATTITUDES AND IDEAS ABOUT ART MUSEUMS .............................12 Perceptions of the Art Museum ..............................................13 Perceptions of Digital Interactives ............................................14 05 OVERALL EXPERIENCE AND IMPACT ....................................15 06 AREAS FOR FURTHER EXPLORATION .....................................17 ABOUT THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART ...................................19 Introduction The Art Museum Digital Impact Evaluation Toolkit in which the experience was studied. The final (AMDIET) is intended to provide artmuseums and version of data collection instruments -

ANNUAL REPORT Report for the Fiscal Year July 1, 2016–June 30, 2017 ANNUAL REPORT Report for the Fiscal Year July 1, 2016– June 30, 2017

ANNUAL REPORT Report for the fiscal year July 1, 2016–June 30, 2017 ANNUAL REPORT Report for the fiscal year July 1, 2016– June 30, 2017 CONTENTS Director’s Foreword..........................................................3 Milestones ................................................................4 Acquisitions ...............................................................5 Exhibitions ................................................................7 Loans ...................................................................10 Clark Fellows .............................................................11 Scholarly Programs ........................................................12 Publications ..............................................................16 Library ..................................................................17 Education ............................................................... 21 Member Events .......................................................... 22 Public Programs ...........................................................27 Financial Report .......................................................... 37 DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD The Clark Art Institute’s new campus has now been fully open for over a year, and these dynamic spaces fostered widespread growth in fiscal year 2017. In particular, the newly reopened Manton Research Center proved that the Clark’s capacity to nurture its diverse community through exhibitions, gallery talks, films, lectures, and musical performances remains one of its greatest strengths. -

Collection Highlights Since Its Founding in 1924, the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts Has Built a Collection of Nearly 5,000 Artworks

Collection Highlights Since its founding in 1924, the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts has built a collection of nearly 5,000 artworks. Enjoy an in-depth exploration of a selection of those artworks acquired by gift, bequest, or purchase support by special donors, as written by staff curators and guest editors over the years. Table of Contents KENOJUAK ASHEVAK Kenojuak Ashevak (ken-OH-jew-ack ASH-uh-vac), one of the most well-known Inuit artists, was a pioneering force in modern Inuit art. Ashevak grew up in a semi-nomadic hunting family and made art in various forms in her youth. However, in the 1950s, she began creating prints. In 1964, Ashevak was the subject of the Oscar-nominated documentary, Eskimo* Artist: Kenojuak, which brought her and her artwork to Canada’s—and the world’s—attention. Ashevak was also one of the most successful members of the Kinngait Co-operative, also known as the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, established in 1959 by James Houston, a Canadian artist and arts administrator, and Kananginak Pootoogook (ka-nang-uh-nak poo-to-guk), an Inuit artist. The purpose of the co-operative is the same as when it was founded—to raise awareness of Inuit art and ensure indigenous artists are compensated appropriately for their work in the Canadian (and global) art market. Ashevak’s signature style typically featured a single animal on a white background. Inspired by the local flora and fauna of the Arctic, Ashevak used bold colors to create dynamic, abstract, and stylized images that are devoid of a setting or fine details. -

California and the Fiber Art Revolution

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2004 California and the Fiber Art Revolution Suzanne Baizerman Oakland Museum of California, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Baizerman, Suzanne, "California and the Fiber Art Revolution" (2004). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 449. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/449 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. California and the Fiber Art Revolution Suzanne Baizerman Imogene Gieling Curator of Crafts and Decorative Arts Oakland Museum of California Oakland, CA 510-238-3005 [email protected] In the 1960s and ‘70s, California artists participated in and influenced an international revolution in fiber art. The California Design (CD) exhibitions, a series held at the Pasadena Art Museum from 1955 to 1971 (and at another venue in 1976) captured the form and spirit of the transition from handwoven, designer textiles to two dimensional fiber art and sculpture.1 Initially, the California Design exhibits brought together manufactured and one-of-a kind hand-crafted objects, akin to the Good Design exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. -

November 5, 2009

ATTACHMENT 2 L ANDMARKSLPC 01-07-10 Page 1 of 18 P RESERVATION C OMMISSION Notice of Decision MEETING OF: November 5, 2009 Property Address: 2525 Telegraph Avenue (2512-16 Regent Street) APN: 055-1839-005 Also Known As: Needham/Obata Building Action: Landmark Designation Application Number: LM #09-40000004 Designation Author(s): Donna Graves with Anny Su, John S. English, and Steve Finacom WHEREAS, the proposed landmarking of 2525 Telegraph Avenue, the Needham/Obata Building, was initiated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission at its meeting on February 5, 2009; and WHEREAS, the proposed landmarking of the Needham/Obata Building is exempt from CEQA pursuant to Section 15061.b.3 (activities that can be seen with certainty to have no significant effect on the environment) of the CEQA Guidelines; and WHEREAS, the Landmarks Preservation Commission opened a public hearing on said proposed landmarking on April 2, 2009, and continued the hearing to May 7, 2009, and then to June 4, 2009; and WHEREAS, during the overall public hearing the Landmarks Preservation Commission took public testimony on the proposed landmarking; and WHEREAS, on June 4, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission determined that the subject property is worthy of Landmark status; and WHEREAS, on July 9, 2009, following release of the Notice of Decision (NOD) on June 29, 2009, the property owner Ali Elsami submitted an appeal requesting that the City Council overturn or remand the Landmark decision; and WHEREAS, on September 22, 2009, the City Council considered Staff’s -

Crystal Reports

Unknown American View of Hudson from the West, ca. 1800–1815 Watercolor and pen and black ink on cream wove paper 24.5 x 34.6 cm. (9 5/8 x 13 5/8 in.) Princeton University Art Museum. Gift of Edward Duff Balken, Class of 1897 (x1958-44) Unknown American Figures in a Garden, ca. 1830 Pen and black ink, watercolor and gouache on beige wove paper 47.3 x 60.3 cm. (18 5/8 x 23 3/4 in.) frame: 51 × 64.6 × 3.5 cm (20 1/16 × 25 7/16 × 1 3/8 in.) Princeton University Art Museum. Gift of Edward Duff Balken, Class of 1897 (x1958-45) Unknown American The Milkmaid, ca. 1840 – 1850 Watercolor on wove paper 27.9 x 22.9 cm (11 x 9 in.) Princeton University Art Museum. Gift of Edward Duff Balken, Class of 1897 (x1958-49) John James Audubon, American, 1785–1851 Yellow-throated Vireo, 1827 Watercolor over graphite on cream wove paper mat: 48.7 × 36.2 cm (19 3/16 × 14 1/4 in.) Graphic Arts Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library. Gift of John S. Williams, Class of 1924. Milton Avery, American, 1893–1965 Harbor View with Shipwrecked Hull, 1927 Gouache on black wove paper 45.7 x 30.2 cm. (18 x 11 7/8 in.) Princeton University Art Museum. Bequest of Edward T. Cone, Class of 1939, Professor of Music 1946-1985 (2005-102) Robert Frederick Blum, American, 1857–1903 Chinese street scene, after 1890 Watercolor and gouache over graphite on cream wove paper 22.8 x 15.3 cm. -

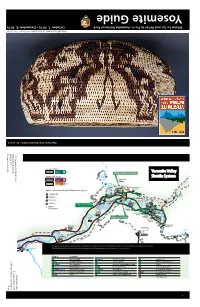

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park October 7, 2015 - December 8, 2015 8, December - 2015 7, October Park National Yosemite in Do to What and Go to Where Butterfly basket made by Julia Parker. Parker. Julia by made basket Butterfly NPS Photo / YOSE 50160 YOSE / Photo NPS Volume 40, Issue 8 Issue 40, Volume America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Summer-only Routes: Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Fall Yosemite Shuttle Village Express Lower Shuttle Yosemite The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System F e E1 5 P2 t i 4 m e 9 Campground os Mirror r Y 3 Uppe 6 10 2 Lake Parking Village Day-use Parking seasonal The Ahwahnee Half Dome Picnic Area 11 P1 1 8836 ft North 2693 m Camp 4 Yosemite E2 Housekeeping Pines Restroom 8 Lodge Lower 7 Chapel Camp Lodge Day-use Parking Pines Walk-In (Open May 22, 2015) Campground LeConte 18 Memorial 12 21 19 Lodge 17 13a 20 14 Swinging Campground Bridge Recreation 13b Reservations Rentals Curry 15 Village Upper Sentinel Village Day-use Parking Pines Beach E7 il Trailhead a r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l E4 Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M ey ses erce all only d R V iver E6 Nevada To & Fall The Valley Visitor Shuttle operates from 7 am to 10 pm and serves stops in numerical order.