Floating World: the Influence of Japanese Printmaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of Art Education in America 1900-1918

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Plan B Papers Student Theses & Publications 7-30-1964 The Development of Art Education in America 1900-1918 Jerry Josserand Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b Recommended Citation Josserand, Jerry, "The Development of Art Education in America 1900-1918" (1964). Plan B Papers. 398. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b/398 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Plan B Papers by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DEVELOPMENT OF ART EDUCATION IN AMERICA 1900-1918 (TITLE) BY Jerry Josserand PLAN B PAPER SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN EDUCATION AND PREPARED IN COURSE Art 591 IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY, CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 1964 YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS PLAN B PAPER BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE DEGREE, M.S. IN ED. This paper was written for Art 591 the summer of 1961. It is the result of historical research in the field of art education. Each student in the class covered an assigned number of years in the development of art education in America. The paper was a section of a booklet composed by the class to cover this field from 1750 up to 1961. The outline form followed in the paper was develpped and required in its writing by the instructor. THE DEVELOPMENT OF ART EDUCATION IN AMERICA 1900-1918 Jerry Josserand I. -

Japonisme and Japanese Works on Paper: Cross-Cultural Influences and Hybrid Materials

Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015 https://icon.org.uk/node/4998 Japonisme and Japanese works on paper: Cross-cultural influences and hybrid materials Rebecca Capua Copyright information: This article is published by Icon on an Open Access basis under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. You are free to copy and redistribute this material in any medium or format under the following terms: You must give appropriate credit and provide a link to the license (you may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way which suggests that Icon endorses you or your use); you may not use the material for commercial purposes; and if you remix, transform, or build upon the material you may not distribute the modified material without prior consent of the copyright holder. You must not detach this page. To cite this article: Rebecca Capua, ‘Japonisme and Japanese works on paper: Cross- cultural influences and hybrid materials’ in Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015 (London, The Institute of Conservation: 2017), 28–42. Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8-10 April 2015 28 Rebecca Capua Japonisme and Japanese works on paper: Cross- cultural and hybrid materials The rise of Japonisme as an artistic movement came at a time when Western artists’ materials and practices were experiencing the impact of industrialization; as artists’ supplies were becoming more commodified and mass-produced, art was disseminated through commercial reproductions and schools were emphasizing the potential for art’s use in the service of industry. -

PROGRAM GUIDE #Apsapril Aps.Org/Meetingapp Aps.Org/Meetings/April

APRIL MEETING 2018 April 14-17, 2018 quarks cosmos Columbus, Ohio Q2C PROGRAM GUIDE #apsapril aps.org/meetingapp aps.org/meetings/april Publish Your High Energy Physics Research in the Physical Review Journals APS supports the high-energy physics (HEP) community by providing authors a free and convenient route to publish HEP* research open access under the APS-SCOAP3 partnership. CHOOSE FROM THESE JOURNALS • No cost to authors Physical Review Letters • CC-BY 4.0 licence Physical Review C • Free global access Physical Review D • Broad dissemination • Greater exposure journals.aps.org *HEP papers covered by SCOAP3 are all those posted on arXiv.org prior to publication in any of the primary ‘hep’ categories: hep-ex, hep-lat, hep-ph, hep-th, and irrespective of the authors’ institution or country affiliation. WELCOME t is a pleasure to welcome you to Columbus, and to the APS April I Meeting 2018. The April Meeting is a wonderful gathering of enthusiastic scientists from diverse organizations and backgrounds who have broad interests in physics. Our meeting provides us with an opportunity to present exciting new work as well as to learn from others, and to meet up with colleagues and make new friends. While you are here, I encourage you to take every opportunity to experience the amazing science that envelops us at the meeting, and to enjoy the many additional professional and social gatherings offered. Additionally, this is a year for Strategic Planning for APS, when the membership will consider the evolving mission of APS and where we want to go as a society. -

CV in English

Sarah Brayer sarahbrayer.com [email protected] ________________ born: Rochester, New York lives: Kyoto, Japan and New York since 1980 Solo Exhibitions 2019 Indra’s Cosmic Net, Daitokuji Studio, Kyoto 2018 Kyoto Passages, The Ren Brown Collection, Bodega Bay, California The Red Thread, Daitokuji Studio, Kyoto 2016 Celestial Threads, Daitokuji Studio, Kyoto ArtHamptons, The Tolman Collection: New York 2015 Luminosity, Hanga Ten, London, England Luminosity, Daitokuji Studio, Kyoto 2014 Between Two Worlds: Poured Paperworks by Sarah Brayer, Castellani Art Museum, Niagara University. catalog In the Moment, Gallery Bonten, Shimonoseki, Japan 2013 Tiger’s Eye, The Verne Collection, Cleveland, Ohio Cloud Garden Paperworks, The Ren Brown Collection, Bodega Bay, California 2012 Luminosity: Night Paperworks, Reike Studio, Santa Fe, New Mexico Light and Energy, Gallery Bonten, Shimonoseki, Japan Recent Works by Sarah Brayer, The Tolman Collection: New York 2011 East Meets West, The Tolman Collection, New York, NY New Works in Washi & Glass, Gallery Shinmonzen, Kyoto The Schoolhouse Gallery, Mutianyu, Beijing, China Gallery Bonten, Shimonoseki, Japan 2010 Luminosity: Night Paperworks, Kamigamo Studio, Kyoto Mythos, The Ren Brown Collection, Bodega Bay, California Art in June, Rochester, New York 30 Years of Art in Kyoto: Sarah Brayer Studio, Kyoto 2007 The Ren Brown Collection, Bodega Bay Gallery Bonten, Shimonoseki, Japan Round the Horn, Nantucket Art in June, Rochester, New York 2006 Whisper to the Moon, Iwakura Kukan, Kyoto Art in June, Rochester, -

The Monongalia County Court House Mural: Blanche Lazzell and the Public Works of Art Project in Morgantown, West Virginia

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2012 The Monongalia County Court House Mural: Blanche Lazzell and the Public Works of Art Project in Morgantown, West Virginia Kendall Joy Martin Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Kendall Joy, "The Monongalia County Court House Mural: Blanche Lazzell and the Public Works of Art Project in Morgantown, West Virginia" (2012). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7803. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7803 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Monongalia County Courthouse Mural: Blanche Lazzell and the Public Works of Art Project in Morgantown, West Virginia. Kendall Joy Martin Thesis Submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Examining Committee Rhonda Reymond, Ph.D., Chair School of Art and Design Janet Snyder, Ph.D. -

Research Resources at the Smithsonian American Art Museum Amelia A

From La Farge to Paik Research Resources at the Smithsonian American Art Museum Amelia A. Goerlitz A wealth of materials related to artistic interchange between the United States and Asia await scholarly attention at the Smithsonian Institution.1 The Smithsonian American Art Museum in particular owns a remarkable number of artworks that speak to the continuous exchange between East and West. Many of these demonstrate U.S. fascination with Asia and its cultures: prints and paintings of America’s Chinatowns; late-nineteenth- century examples of Orientalism and Japonisme; Asian decorative arts and artifacts donated by an American collector; works by Anglo artists who trav- eled to Asia and India to depict their landscapes and peoples or to study traditional printmaking techniques; and post-war paintings that engage with Asian spirituality and calligraphic traditions. The museum also owns hundreds of works by artists of Asian descent, some well known, but many whose careers are just now being rediscovered. This essay offers a selected overview of related objects in the collection. West Looks East American artists have long looked eastward—not only to Europe but also to Asia and India—for subject matter and aesthetic inspiration. They did not al- ways have to look far. In fact, the earliest of such works in the American Art Mu- seum’s collection consider with curiosity, and sometimes animosity, the presence of Asians in the United States. An example is Winslow Homer’s engraving enti- tled The Chinese in New York—Scene in a Baxter Street Club-House, which was produced for Harper’s Weekly in 1874. -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia americká architektúra - pozri chicagská škola, prériová škola, organická architektúra, Queen Anne style v Spojených štátoch, Usonia americká ilustrácia - pozri zlatý vek americkej ilustrácie americká retuš - retuš americká americká ruleta/americké zrnidlo - oceľové ozubené koliesko na zahnutej ose, užívané na zazrnenie plochy kovového štočku; plocha spracovaná do čiarok, pravidelných aj nepravidelných zŕn nedosahuje kvality plochy spracovanej kolískou americká scéna - american scene americké architektky - pozri americkí architekti http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_architects americké sklo - secesné výrobky z krištáľového skla od Luisa Comforta Tiffaniho, ktoré silno ovplyvnili európsku sklársku produkciu; vyznačujú sa jemnou farebnou škálou a novými tvarmi americké litografky - pozri americkí litografi http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_printmakers A Anne Appleby Dotty Atti Alicia Austin B Peggy Bacon Belle Baranceanu Santa Barraza Jennifer Bartlett Virginia Berresford Camille Billops Isabel Bishop Lee Bontec Kate Borcherding Hilary Brace C Allie máj "AM" Carpenter Mary Cassatt Vija Celminš Irene Chan Amelia R. Coats Susan Crile D Janet Doubí Erickson Dale DeArmond Margaret Dobson E Ronnie Elliott Maria Epes F Frances Foy Juliette mája Fraser Edith Frohock G Wanda Gag Esther Gentle Heslo AMERICKÁ - AMES Strana 1 z 152 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia Charlotte Gilbertson Anne Goldthwaite Blanche Grambs H Ellen Day -

October 2007

Number 34 Fall 2007 NE W SLETTER MAHS Conference 2008, Chicago, Illinois, April 2-5, 2008 The Midwest Art History Society’s 35th annual meeting will be The MAHS business lunch will take place on Friday. On Friday held April 2-5, 2008 in Chicago. Hosted by Loyola University, evening the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Columbia Columbia College and the Art Institute of Chicago, the con- College Chicago, 600 S. Michigan, www.mcop.org will be the ference takes place with the partnership of DePaul University, location of a MAHS reception. Saturday morning, April 5, The Lake Forest College, and the School of the Art Institute Museum of Contemporary Art, 220 East Chicago Avenue, www. Chicago. Further assistance has been provided by the Museum of mcachicago.org, will host an early opening, continental breakfast, Contemporary Art and the Terra Foundation for the Arts. The and curator’s tour of the current exhibitions – “Alexander Calder conference hotel will be the Club Quarters, conveniently located in Focus” and selections of the museum’s permanent collection. in Chicago’s Loop at W. Adams Street. The conference’s morning sessions will also be held at the MCA. The conference sessions and programs Loyola University Museum of Art, 820 North Michigan Avenue have been selected with an eye to (just two blocks west of the MCA) www. showcasing areas of specialization luc.edu/LUMA, will be the site of a closely associated with Chicago and luncheon on Saturday. The conference’s its educational and cultural insti- afternoon sessions will be held at LUMA tutions. Additional emphases on on Saturday where “Gilded Glory: American and Renaissance art have European Treasures from the Martin been designed to coordinate with D’Arcy Collection” will be on view. -

The Modernist Studies Association Conference 2018 “Graphic Modernisms” Hilton Columbus Downtown Columbus, OH November 8-11, 2018

The Modernist Studies Association Conference 2018 “Graphic Modernisms” Hilton Columbus Downtown Columbus, OH November 8-11, 2018 Statement on Transgender Inclusion The Modernist Studies Association affirms and stands in support of the rights and dignity of our transgender and gender non-binary members and all other persons associated with our organization and conference. We believe that inclusivity, diversity, access, and equality are critical to the strength of our organization and the effectiveness of our academic mission. We are committed to maintaining a welcoming and inclusive organization where everyone can be their full self. This goal includes the practice of using individuals’ preferred name and pronoun reference when introducing speakers or citing their work or ideas. Special Events Plenary Sessions Plenary Session 1: A Conversation with Joe Sacco Thursday, 7:00pm - 8:15 pm Joe Sacco is an acclaimed graphic journalist and author of Palestine and Footnotes in Gaza, on the Israel-Palestine conflict, and Safe Area Gorazde and The Fixer, on the Bosnian War. He’s lived in Malta and the U.S., and has published additional pieces on blues music, war crimes, and Chechen refugees. His work has won the American Book Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and the Eisner Award. His recently published collaboration with Matt Hern and Am Johal, Global Warming and the Sweetness of Life, explores ecology and climate change in the tar sands region of Canada. Joe Sacco will be interviewed by Jared Gardner, Professor of English at Ohio State University and author of Projections: Comics and the History of 21st-century Storytelling (2012), The Rise and Fall of Early American Magazine Culture (2012), and Master Plots: Race and the Founding of an American Literature 1787-1845 (1998). -

Women's Studies Librarian on Women, Gender, And

WOMEN’S STUDIES LIBRARIAN NEW BOOKS ON WOMEN, GENDER, AND FEMINISM Numbers 54–55 Spring–Fall 2009 University of Wisconsin System NEW BOOKS ON WOMEN, GENDER, & FEMINISM Nos. 54–55, Spring–Fall 2009 CONTENTS Scope Statement .................. 1 Reference/ Bibliography . 37 Anthropology...................... 1 Religion/ Spirituality . 38 Art/ Architecture/ Photography . 2 Science/ Mathematics/ Technology . 42 Biography ........................ 4 Sexuality ........................ 42 Economics/ Business/ Work . 8 Sociology/ Social Issues . 43 Education ....................... 10 Sports & Recreation . 47 Film/ Theater..................... 11 Women’s Movement/ General Women's Studies . 48 Health/ Medicine/ Biology . 12 Periodicals ...................... 49 History.......................... 15 Indexes Humor.......................... 19 Authors, Editors, & Translators . 51 Language/ Linguistics . 20 Subjects....................... 63 Law ............................ 20 Citation Abbreviations . 83 Lesbian Studies .................. 22 Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, & Queer Studies . 22 New Books on Women, Gender, & Feminism is published by Literature Phyllis Holman Weisbard, Women's Studies Librarian for the University of Wisconsin System, 430 Memorial Library, 728 Drama ........................ 23 State Street, Madison, WI 53706. Phone: (608) 263-5754. Fiction ........................ 24 Email: wiswsl @library.wisc.edu. Editor: Linda Fain. Compilers: Elzbieta Beck, Madelyn R. Homuth, JoAnne Lehman, Heather History & Criticism -

The Cape Cod School Of

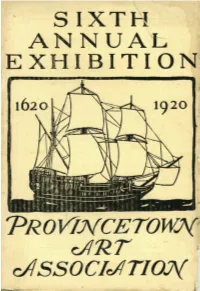

S IXTH ANNUAL IBITION PROVINCETOWN ART ASSOCIATION ! FOR SERVICEAND QUALITY Buy Direct from the Maker Newcomb - Macklin Co. ARTISTS’ MATERIALS C. G. MACKLIN, President J. SUSTER, Secretary OF ALL DESCRIPTIONS PICTURE FRAME MAKERS FAVOR, RUHL &CO. NEW YORK BOSTON CHICAGO DISTINGUISHED DESIGNS AND FINISHES SUPERIOR WORKMANSHIP LOWEST PRICES IF YOU WANT PURITY OF TONE AND TRUE COLORS, ASK FOR DEVOE ARTISTS OIL COLORS IN TUBES 233 Fifth Avenue, NEW YORK GEORGE A. McCOY, Manager THE OLDEST COLOR MAKERS ESTABLISHED, 1754 Factory : State and Kinzie Streets, CHICAGO DEVOE & RAYNOLDS CO. Catalogues sent to Artists and Dealers NEW YORK CHICAGO KANSAS CITY WEST END SCHOOL OF ART Provincetown Art Association LANDSCAPE AND FIGURE PAINTING Founded 1914 OIL AND WATER COLOR Provincetown, Massachusetts GEORGE ELMER BROWNE, Instructor SIXTH 1 62 Commercial Street, Provincetown ANNUAL EXHIBITION 1920 JULY 4TH TO AUGUST 31st The Cape School of Art Cod JURY AND HANGING COMMITTEE Instructor. CHARLES W. HAWTHORNE Max Bohm Charles W. Hawthorne, N. A. Assistant Instructor, OSCAR H. GIEBERICH E. Ambrose Webster Oliver Chaffee Director. HARRY N CAMPBELL George Elmer Browne Ethel Mars Mrs. Henry Mottet SEASON OF 1920 July 5th to August 28th, 1920 ADMISSION,10 CENTS FREEON SUNDAYS,1 TO 5 P. M. OFFICERS WILLIAM H. YOUNG, President PAINTING CLASS CHARLES W. HAWTHORNE, N. A, Vice President IN E AMBROSE WEBSTER. Vice President MRS. EUGENE WATSON, Acting Vice President BERMUDA MRS ANNA M. YOUNG, Treasurer MISS NINA S. WILLIAMS, Recording secretary E. A. WEBSTER, INSTRUCTOR MYRICK C. ATWOOD, Corresponding Secretary DEC. 1, 1919, TO FEB. 1, 1920 E. A MBROSE WEBSTER, Director ARTS & DECORATION ARTISTS’ MATERIALS 35 CENTS A COPY, $4.00 A YEAR OF ALL KINDS AT CITY PRICES 25 West Forty Third Street New York, N. -

Squire, Maud Hunt (1873-1955) and Ethel Mars (1876-1956) by Ruth M

Squire, Maud Hunt (1873-1955) and Ethel Mars (1876-1956) by Ruth M. Pettis Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2005, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com American artists and life partners Maud Hunt Squire and Ethel Mars forged distinguished careers in book illustration, painting, and woodblock printing. Émigrées to France, they frequented Gertrude Stein's salons and, during World War I, were among the Provincetown artists working in new methods of printmaking. Maud Squire was born January 30, 1873 in Cincinnati. Her parents encouraged her artistic training, though both had died by the time she was a young woman. At the age of 21, she enrolled in the Cincinnati Art Academy and studied under Lewis Henry Meakin and Frank Duveneck. At the academy she met fellow student Ethel Mars, with whom she would live and travel for the rest of her life. Mars, born in Springfield, Illinois on September 19, 1876, was the only child of a railroad employee and a homemaker. From 1892 to 1897, she studied illustration and drawing at the Cincinnati Art Academy. Squire began her career while still a student, traveling to New York to meet with publishers and exhibiting her work. By 1900 she and Mars were living in New York City, traveling to Europe, and collaborating on illustrating children's books, such as Charles Kingsley's The Heroes (1901). By 1906 they had settled in Paris together. Paris at the turn of the twentieth century had become a magnet for American women with artistic aspirations. As described by artist Anne Goldthwaite, Squire and Mars were prim "Middle Western" girls when they arrived in Paris.