Edna Boies Hopkins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM of ART ANNUAL REPORT 2002 1 0-Cover.P65 the CLEVELAND MUSEUM of ART

ANNUAL REPORT 2002 THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART REPORT 2002 ANNUAL 0-Cover.p65 1 6/10/2003, 4:08 PM THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART ANNUAL REPORT 2002 1-Welcome-A.p65 1 6/10/2003, 4:16 PM Feathered Panel. Peru, The Cleveland Narrative: Gregory Photography credits: Brichford: pp. 7 (left, Far South Coast, Pampa Museum of Art M. Donley Works of art in the both), 9 (top), 11 Ocoña; AD 600–900; 11150 East Boulevard Editing: Barbara J. collection were photo- (bottom), 34 (left), 39 Cleveland, Ohio Bradley and graphed by museum (top), 61, 63, 64, 68, Papagayo macaw feathers 44106–1797 photographers 79, 88 (left), 92; knotted onto string and Kathleen Mills Copyright © 2003 Howard Agriesti and Rodney L. Brown: p. stitched to cotton plain- Design: Thomas H. Gary Kirchenbauer 82 (left) © 2002; Philip The Cleveland Barnard III weave cloth, camelid fiber Museum of Art and are copyright Brutz: pp. 9 (left), 88 Production: Charles by the Cleveland (top), 89 (all), 96; plain-weave upper tape; All rights reserved. 81.3 x 223.5 cm; Andrew R. Szabla Museum of Art. The Gregory M. Donley: No portion of this works of art them- front cover, pp. 4, 6 and Martha Holden Jennings publication may be Printing: Great Lakes Lithograph selves may also be (both), 7 (bottom), 8 Fund 2002.93 reproduced in any protected by copy- (bottom), 13 (both), form whatsoever The type is Adobe Front cover and frontispiece: right in the United 31, 32, 34 (bottom), 36 without the prior Palatino and States of America or (bottom), 41, 45 (top), As the sun went down, the written permission Bitstream Futura abroad and may not 60, 62, 71, 77, 83 (left), lights came up: on of the Cleveland adapted for this be reproduced in any 85 (right, center), 91; September 11, the facade Museum of Art. -

PAAM Collection Oct 18.Pdf

First Middle Last Birth Death Sex Accession Acc ext Media code Title Date Medium H W D Finished size Credit Jules Aarons 1921 2008 m 1828 Ph06 Jules Aarons Portfolio: In the Jewish Neighborhoods 1946-76 box, 100 silver gelatin prints, signed verso 15.5 12 3 Gift of David Murphy, 2006 Jules Aarons 1921 2008 m 1928 001 Ph08 untitled (Weldon Kees speaking to assembly of artists) c.1949-50 silver gelatin photograph 8 10 Gift of David Murphy, 2008 Jules Aarons 1921 2008 m 1928 002 Ph08 Sunday (The fishermen's children playing on the loading wharf.) c.1949-50 silver gelatin photograph 8 9.5 Gift of David Murphy, 2008 Jules Aarons 1921 2008 m 1928 003 Ph08 untitled (Sunday II, fishermen's children playing on loading wharf.) c.1949-50 silver gelatin photograph 8 10 Gift of David Murphy, 2008 Jules Aarons 1921 2008 m 1928 004 Ph08 untitled (the flag bearers) c.1949-50 silver gelatin photograph 8 10 Gift of David Murphy, 2008 Jules Aarons 1921 2008 m 1928 005 Ph08 Parting c.1949-50 silver gelatin photograph 9 7 Gift of David Murphy, 2008 Jules Aarons 1921 2008 m 1928 006 Ph08 untitled (2 ladies at an exhibition) c.1949-50 silver gelatin photograph 7.5 9.5 Gift of David Murphy, 2008 Jules Aarons 1921 2008 m 1928 007 Ph08 Dante (I, Giglio Raphael Dante sitting on floor, ptg. behind) c.1949-50 silver gelatin photograph 10 8 Gift of David Murphy, 2008 Jules Aarons 1921 2008 m 1928 008 Ph08 Lawrence Kupferman, a Prominent Modern American Artist (etc.) c.1949-50 silver gelatin photograph 7.5 9.5 Gift of David Murphy, 2008 Jules Aarons 1921 2008 m 1928 009 Ph08 Kahlil (Gibran, playing music on bed) c.1949-50 silver gelatin photograph 7 7.5 Gift of David Murphy, 2008 Jules Aarons 1921 2008 m 1928 010 Ph08 Kahlil & Ellie G. -

Floating World: the Influence of Japanese Printmaking

Floating World: The Influence of Japanese Printmaking Ando Hiroshige, Uraga in Sagami Province, from the series Harbors of Japan, 1840-42, color woodcut, collection of Ginna Parsons Lagergren Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Poem by Sarumaru Tayû: Soga Hakoômaru, from the series Ogura Imitations of One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets, 1845-48, color woodcut, collection of Jerry & Judith Levy Floating World: The Influence of Japanese Printmaking June 14–August 24, 2013 Floating World explores the influence of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock printmaking on American and European artists from the late 19th century to the present. A selection of Japanese prints sets the stage for Arts & Crafts era works by Charles Bartlett, Elizabeth Colborne, Arthur Wesley Dow, Frances Gearhart, Edna Boies Hopkins, Bertha Lum and Margaret Jordan Patterson. Woodcuts by Helen Franken- thaler illuminate connections between Abstract Expressionism and Japanese art. Prints by Annie Bissett, Kristina Hagman, Ellen Heck, Tracy Lang, Eva Pietzcker and Roger Shimomura illustrate the ongo- ing allure of ukiyo-e as the basis for innovations in printmaking today. In 1891, AmerIcAn ArtisT woodblock prints that depicted the ARThuR WESLEY DOW wrote that “floating world” of leisure and en- “one evening with Hokusai gave me tertainment. Artists began depicting more light on composition and deco- teahouses, festivals, theater and activi- rative effect than years of study of ties like the tea ceremony, flower ar- pictures. I surely ought to compose in an ranging, painting, calligraphy and music. entirely different manner.”1 Dow wrote Landscapes, birds, flowers and scenes of the letter after discovering a book of daily life were also popular. -

The Development of Art Education in America 1900-1918

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Plan B Papers Student Theses & Publications 7-30-1964 The Development of Art Education in America 1900-1918 Jerry Josserand Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b Recommended Citation Josserand, Jerry, "The Development of Art Education in America 1900-1918" (1964). Plan B Papers. 398. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b/398 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Plan B Papers by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DEVELOPMENT OF ART EDUCATION IN AMERICA 1900-1918 (TITLE) BY Jerry Josserand PLAN B PAPER SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN EDUCATION AND PREPARED IN COURSE Art 591 IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY, CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 1964 YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS PLAN B PAPER BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE DEGREE, M.S. IN ED. This paper was written for Art 591 the summer of 1961. It is the result of historical research in the field of art education. Each student in the class covered an assigned number of years in the development of art education in America. The paper was a section of a booklet composed by the class to cover this field from 1750 up to 1961. The outline form followed in the paper was develpped and required in its writing by the instructor. THE DEVELOPMENT OF ART EDUCATION IN AMERICA 1900-1918 Jerry Josserand I. -

American Prints 1860-1960

American Prints 1860-1960 from the collection of Matthew Marks American Prints 1860-1960 from the collection of Matthew Marks American Prints 1860-1960 from the collection of Matthew Marks Bennington College, Bennington, Vermont Introduction The 124 prints which make up this exhibition have been selected from my collection of published on the occasion over 800 prints. The works exhibited at Bennington have been confined to those made by ot an exhibitionat the American artists between 1860 and 1960. There are European and contemporary prints in my A catalogue suchasthis and the exhibitionwhich collection but its greatest strengths are in the area of American prints. The dates 1860 to Suzanne Lemberg Usdan Gallery accompaniesit.. is ot necessity a collaborativeeffortand 1960, to which I have chosen to confine myself, echo for the most part my collecting Bennington College would nothave been possible without thesupport and interests. They do, however, seem to me to be a logical choice for the exhibition. lt V.'CIS Bennington \'ermonr 05201 cooperation of many people. around 1860 that American painters first became incerested in making original prints and it April 9 to May9 1985 l am especially graceful to cbe Bennington College Art was about a century later, in the early 1960s, that several large printmaking workshops were Division for their encouragementand interestin this established. An enormous rise in the popularity of printmaking as an arcistic medium, which projectfrom thestart. In particular I wouldlike co we are still experiencing today, occurred at that cime. Copyright © 1985 by MatthewMarks thankRochelle Feinstein. GuyGood... in; andSidney The first American print to enter my collection, the Marsden Hartley lirhograph TilJim, who originally suggestedche topicof theexhibi- (Catalogue #36 was purchased nearly ten years ago. -

A Stellar Century of Cultivating Culture

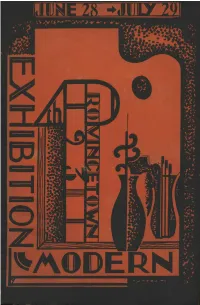

COVERFEATURE THE PAAMPROVINCETOWN ART ASSOCIATION AND MUSEUM 2014 A Stellar Century of Cultivating Culture By Christopher Busa Certainly it is impossible to capture in a few pages a century of creative activity, with all the long hours in the studio, caught between doubt and decision, that hundreds of artists of the area have devoted to making art, but we can isolate some crucial directions, key figures, and salient issues that motivate artists to make art. We can also show why Provincetown has been sought out by so many of the nation’s notable artists, performers, and writers as a gathering place for creative activity. At the center of this activity, the Provincetown Art Associ- ation, before it became an accredited museum, orga- nized the solitary efforts of artists in their studios to share their work with an appreciative pub- lic, offering the dynamic back-and-forth that pushes achievement into social validation. Without this audience, artists suffer from lack of recognition. Perhaps personal stories are the best way to describe PAAM’s immense contribution, since people have always been the true life source of this iconic institution. 40 PROVINCETOWNARTS 2014 ABOVE: (LEFT) PAAM IN 2014 PHOTO BY JAMES ZIMMERMAN, (righT) PAA IN 1950 PHOTO BY GEORGE YATER OPPOSITE PAGE: (LEFT) LUCY L’ENGLE (1889–1978) AND AGNES WEINRICH (1873–1946), 1933 MODERN EXHIBITION CATALOGUE COVER (PAA), 8.5 BY 5.5 INCHES PAAM ARCHIVES (righT) CHARLES W. HAwtHORNE (1872–1930), THE ARTIST’S PALEttE GIFT OF ANTOINETTE SCUDDER The Armory Show, introducing Modernism to America, ignited an angry dialogue between conservatives and Modernists. -

Japonisme and Japanese Works on Paper: Cross-Cultural Influences and Hybrid Materials

Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015 https://icon.org.uk/node/4998 Japonisme and Japanese works on paper: Cross-cultural influences and hybrid materials Rebecca Capua Copyright information: This article is published by Icon on an Open Access basis under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. You are free to copy and redistribute this material in any medium or format under the following terms: You must give appropriate credit and provide a link to the license (you may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way which suggests that Icon endorses you or your use); you may not use the material for commercial purposes; and if you remix, transform, or build upon the material you may not distribute the modified material without prior consent of the copyright holder. You must not detach this page. To cite this article: Rebecca Capua, ‘Japonisme and Japanese works on paper: Cross- cultural influences and hybrid materials’ in Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015 (London, The Institute of Conservation: 2017), 28–42. Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8-10 April 2015 28 Rebecca Capua Japonisme and Japanese works on paper: Cross- cultural and hybrid materials The rise of Japonisme as an artistic movement came at a time when Western artists’ materials and practices were experiencing the impact of industrialization; as artists’ supplies were becoming more commodified and mass-produced, art was disseminated through commercial reproductions and schools were emphasizing the potential for art’s use in the service of industry. -

Blanche Lazzell

ESTABLISHED OVER FIFTY years Newcomb-Macklin co. Picture Frame Makers 45 WEST 27th STREET Sailing from Long Wharf NEW YORK STOCK FRAMES change without notice FOR IMMEDIATE DELIVERY inall wn to Boston Regular Sizes at Lowest Prices at 7:30 p. m. Due in boson RELIABLE QUALITY-VALUE-SERVICE DANCING R COMPARE! ONE WAY FARE $1.75 EXCURSION ROUND T MAIL ORDERS Receive Careful, Prompt, Individual Attention Boston Tel. Hubbard 9392 GEORGE A. McCoy, Manager Catalog sent to artists and deaJers on request REMBRANDT BEHRENDT COLORS Oil Colors PFEIFFERS' PROVINCETOWN, MASS. Distributors for U. S. J. S. distributing office at TALENS & SON irvington N. J. APELDOORN, HOLLAND ARTISTS' SUPPLIES books John A. matheson Pres. H. F. Hallett, Vice Pres and Cashier I. A. Small, Asst. Cashier W. T. Mayo, Asst. Cashier WILLIAM H. YOUNG THE FIRST NATIONAL BANK INSURANCE OF EVERY DESCRIPTION of Provincetown Capital Stock, Surplus and Profits, $125,457 representing the leading companies of the World Money deposited in our Savings Department placed on interest the first of each month losses Adjusted promptly Checking Accounts Savings Accounts Safe Deposit Boxes Foreign Exchange provincetown massachusetts Travelers’ Checks SEAMEN’S SAVINGS BANK THE exhibition IS OPEN DAILY FROM Provincetown Mass. A. M. to P. M. ADMISSION CENTS. SUNDAYS, FREE FROM to P. M. Money Goes on Interest the First of Each Month Join the Provincetown Art Association Not only because it is an association of artists and lovers of art, but also because it offers its members (and often ita friends), dances, lectures, music recitals, and a won- derful Costume Ball, which latter will come this year EITHER THE ATTENDANT AT THE DESK at Hall in August. -

PROGRAM GUIDE #Apsapril Aps.Org/Meetingapp Aps.Org/Meetings/April

APRIL MEETING 2018 April 14-17, 2018 quarks cosmos Columbus, Ohio Q2C PROGRAM GUIDE #apsapril aps.org/meetingapp aps.org/meetings/april Publish Your High Energy Physics Research in the Physical Review Journals APS supports the high-energy physics (HEP) community by providing authors a free and convenient route to publish HEP* research open access under the APS-SCOAP3 partnership. CHOOSE FROM THESE JOURNALS • No cost to authors Physical Review Letters • CC-BY 4.0 licence Physical Review C • Free global access Physical Review D • Broad dissemination • Greater exposure journals.aps.org *HEP papers covered by SCOAP3 are all those posted on arXiv.org prior to publication in any of the primary ‘hep’ categories: hep-ex, hep-lat, hep-ph, hep-th, and irrespective of the authors’ institution or country affiliation. WELCOME t is a pleasure to welcome you to Columbus, and to the APS April I Meeting 2018. The April Meeting is a wonderful gathering of enthusiastic scientists from diverse organizations and backgrounds who have broad interests in physics. Our meeting provides us with an opportunity to present exciting new work as well as to learn from others, and to meet up with colleagues and make new friends. While you are here, I encourage you to take every opportunity to experience the amazing science that envelops us at the meeting, and to enjoy the many additional professional and social gatherings offered. Additionally, this is a year for Strategic Planning for APS, when the membership will consider the evolving mission of APS and where we want to go as a society. -

CV in English

Sarah Brayer sarahbrayer.com [email protected] ________________ born: Rochester, New York lives: Kyoto, Japan and New York since 1980 Solo Exhibitions 2019 Indra’s Cosmic Net, Daitokuji Studio, Kyoto 2018 Kyoto Passages, The Ren Brown Collection, Bodega Bay, California The Red Thread, Daitokuji Studio, Kyoto 2016 Celestial Threads, Daitokuji Studio, Kyoto ArtHamptons, The Tolman Collection: New York 2015 Luminosity, Hanga Ten, London, England Luminosity, Daitokuji Studio, Kyoto 2014 Between Two Worlds: Poured Paperworks by Sarah Brayer, Castellani Art Museum, Niagara University. catalog In the Moment, Gallery Bonten, Shimonoseki, Japan 2013 Tiger’s Eye, The Verne Collection, Cleveland, Ohio Cloud Garden Paperworks, The Ren Brown Collection, Bodega Bay, California 2012 Luminosity: Night Paperworks, Reike Studio, Santa Fe, New Mexico Light and Energy, Gallery Bonten, Shimonoseki, Japan Recent Works by Sarah Brayer, The Tolman Collection: New York 2011 East Meets West, The Tolman Collection, New York, NY New Works in Washi & Glass, Gallery Shinmonzen, Kyoto The Schoolhouse Gallery, Mutianyu, Beijing, China Gallery Bonten, Shimonoseki, Japan 2010 Luminosity: Night Paperworks, Kamigamo Studio, Kyoto Mythos, The Ren Brown Collection, Bodega Bay, California Art in June, Rochester, New York 30 Years of Art in Kyoto: Sarah Brayer Studio, Kyoto 2007 The Ren Brown Collection, Bodega Bay Gallery Bonten, Shimonoseki, Japan Round the Horn, Nantucket Art in June, Rochester, New York 2006 Whisper to the Moon, Iwakura Kukan, Kyoto Art in June, Rochester, -

The Monongalia County Court House Mural: Blanche Lazzell and the Public Works of Art Project in Morgantown, West Virginia

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2012 The Monongalia County Court House Mural: Blanche Lazzell and the Public Works of Art Project in Morgantown, West Virginia Kendall Joy Martin Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Kendall Joy, "The Monongalia County Court House Mural: Blanche Lazzell and the Public Works of Art Project in Morgantown, West Virginia" (2012). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7803. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7803 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Monongalia County Courthouse Mural: Blanche Lazzell and the Public Works of Art Project in Morgantown, West Virginia. Kendall Joy Martin Thesis Submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Examining Committee Rhonda Reymond, Ph.D., Chair School of Art and Design Janet Snyder, Ph.D. -

Research Resources at the Smithsonian American Art Museum Amelia A

From La Farge to Paik Research Resources at the Smithsonian American Art Museum Amelia A. Goerlitz A wealth of materials related to artistic interchange between the United States and Asia await scholarly attention at the Smithsonian Institution.1 The Smithsonian American Art Museum in particular owns a remarkable number of artworks that speak to the continuous exchange between East and West. Many of these demonstrate U.S. fascination with Asia and its cultures: prints and paintings of America’s Chinatowns; late-nineteenth- century examples of Orientalism and Japonisme; Asian decorative arts and artifacts donated by an American collector; works by Anglo artists who trav- eled to Asia and India to depict their landscapes and peoples or to study traditional printmaking techniques; and post-war paintings that engage with Asian spirituality and calligraphic traditions. The museum also owns hundreds of works by artists of Asian descent, some well known, but many whose careers are just now being rediscovered. This essay offers a selected overview of related objects in the collection. West Looks East American artists have long looked eastward—not only to Europe but also to Asia and India—for subject matter and aesthetic inspiration. They did not al- ways have to look far. In fact, the earliest of such works in the American Art Mu- seum’s collection consider with curiosity, and sometimes animosity, the presence of Asians in the United States. An example is Winslow Homer’s engraving enti- tled The Chinese in New York—Scene in a Baxter Street Club-House, which was produced for Harper’s Weekly in 1874.