New Pathways in Civil Rights Historiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Women As Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools During the 1950S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Hostos Community College 2019 Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools during the 1950s Kristopher B. Burrell CUNY Hostos Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ho_pubs/93 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] £,\.PYoo~ ~ L ~oto' l'l CILOM ~t~ ~~:t '!Nll\O lit.ti t~ THESTRANGE CAREERS OfTHE JIMCROW NORTH Segregation and Struggle outside of the South EDITEDBY Brian Purnell ANOJeanne Theoharis, WITHKomozi Woodard CONTENTS '• ~I') Introduction. Histories of Racism and Resistance, Seen and Unseen: How and Why to Think about the Jim Crow North 1 Brian Purnelland Jeanne Theoharis 1. A Murder in Central Park: Racial Violence and the Crime NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS Wave in New York during the 1930s and 1940s ~ 43 New York www.nyupress.org Shannon King © 2019 by New York University 2. In the "Fabled Land of Make-Believe": Charlotta Bass and All rights reserved Jim Crow Los Angeles 67 References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or John S. Portlock changed since the manuscript was prepared. 3. Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in Names: Purnell, Brian, 1978- editor. -

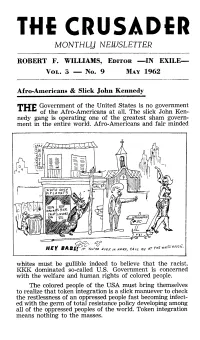

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

Africa Latin America Asia 110101101

PL~ Africa Latin America Asia 110101101 i~ t°ica : 4 shilhnns Eurnna " fi F 9 ahillinnc Lmarica - .C' 1 ;'; Africa Latin America Asia Incorporating "African Revolution" DIRECTOR J. M . Verg6s EDITORIAL BOARD Hamza Alavi (Pakistan) Richard Gibson (U .S.A.) A. R. Muhammad Babu (Zanzibar) Nguyen Men (Vietnam) Amilcar Cabrera (Venezuela) Hassan Riad (U.A .R .) Castro do Silva (Angola) BUREAUX Britain - 4. Leigh Street, London, W. C. 1 China - A. M. Kheir, 9 Tai Chi Chang, Peking ; distribution : Guozj Shudian, P.O . Box 399, Peking (37) Cuba - Revolucibn, Plaza de la Revolucibn, Havana ; tel. : 70-5591 to 93 France - 40, rue Franqois lei, Paris 8e ; tel. : ELY 66-44 Tanganyika - P.O. Box 807, Dar es Salaam ; tel. : 22 356 U .S.A. - 244 East 46th Street, New York 17, N. Y. ; tel. : YU 6-5939 All enquiries concerning REVOLUTION, subscriptions, distribution and advertising should be addressed to REVOLUTION M6tropole, 10-11 Lausanne, Switzerland Tel . : (021) 22 00 95 For subscription rates, see page 240. PHOTO CREDITS : Congress of Racial Equality, Bob Adelman, Leroy McLucas, Associated Press, Photopress Zurich, Bob Parent, William Lovelace pp . 1 to 25 ; Leroy LcLucas p . 26 ; Agence France- Presse p . 58 ; E . Kagan p . 61 ; Photopress Zurich p . 119, 122, 126, 132, 135, 141, 144,150 ; Ghana Informa- tion Service pp . 161, 163, 166 ; L . N . Sirman Press pp . 176, 188 ; Camera Press Ltd, pp . 180, 182, 197, 198, 199 ; Photojournalist p . 191 ; UNESCO p . 195 ; J .-P . Weir p . 229 . Drawings, cartoons and maps by Sine, Strelkoff, N . Suba and Dominique and Frederick Gibson . -

Robert F. Williams, Negroes with Guns, Ch. 3-5, 1962

National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox The Making of African American Identity: Vol. III, 1917-1968 Robert F. Williams R. C. Cohen Negroes With Guns *1962, Ch. 3-5 Robert F. Williams was born and raised in Monroe, North Carolina. After serving in the Marine Cops in the 1950s, he returned to Monroe and in 1956 assumed leadership of the nearly defunct local NAACP chapter; within six months its membership grew from six to two-hundred. Many of the new members were, like him, military veterans trained in the use of arms. In the late 1950s the unwillingness of Southern officials to address white violence against blacks made it increasingly difficult for the NAACP to keep all of its local chapters committed to non-violence. In 1959, after three white men were acquitted of assaulting black women in Monroe, Williams publicly proclaimed the right of African Americans to armed self-defense. The torrent of criticism this statement brought down on the NAACP prompted its leaders — including Thurgood Marshall, Roy Wilkins, and Martin Luther King, Jr. — to denounce Williams. The NAACP eventually suspended him, but he continued to make his case for self-defense. Williams in Tanzania, 1968 Chapter 3: The Struggle for Militancy in the NAACP Until my statement hit the national newspapers the national office of the NAACP had paid little attention to us. We had received little help from them in our struggles and our hour of need. Now they lost no time. The very next morning I received a long distance telephone call from the national office wanting to know if I had been quoted correctly. -

Mae Mallory Papers

THE MAE MALLORY COLLECTION Papers, 1961-1967 (Predominantly, 1962-1963) 1 linear foot Accession Number 955 L.C. Number The papers of Mae Mallory were placed in the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs in January of 1978 by General Baker and were opened for research in December of 1979. Mae Mallory (also known as Willie Mae Mallory) was born in Macon, Georgia on June 9, 1927. She later went to live in New York City with her mother in 1939. She became active in the black civil rights movement and was secretary of the organization, Crusaders for Freedom. She was closely associated with the ultra-militant leader of the NAACP chapter in Monroe, North Carolina, Robert F. Williams, who advocated that blacks arm them- selves in order to defend their rights. In 1961 she, Williams and others were charged with kidnap pong a white couple during a racial disturbance in Monroe. She fled to Cleveland, Ohio, to avoid arrest, but was imprisoned from 1962 to 1964 in the Cuyahoga County Jail to await extradition to North Carolina to face trial. Williams, who, like Mallory, protested his innocence of the charges, fled via Canada to Cuba and later China. In 1964 she was returned to Monroe, stood trial, and was convicted. She appealed the sentence, and in the following year the North Carolina Supreme Court dismissed the case because blacks had been excluded from the grand jury. The material in this collection reflects Mallory's participation in the civil rights movement and documents her period of imprisonment. Important subjects covered in the collection are: Black activism (1960's) Civil rights movement Monroe Defense Committee Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) Robert F. -

Rfwe Must Die: Anned Self-Defense During the Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1967 by Martin Palomo November 25,2018 History 91: Seni

rfWe Must Die: Anned Self-Defense during the Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1967 by Martin Palomo November 25,2018 History 91: Senior Thesis Palomo 1 Abstract This paper looks over the Civil Rights Movement between 1954 and 1967 and analyzes the role that armed self-defense played during this period. By looking at the violence that erupted following the 1954 Brown v. Board ofEducation Supreme Court Case, it becomes evident that African Americans, both men and women, used arms to protect their communities while simultaneously challenging Jim Crow through nonviolent civil disobedience. By the mid-1960s, armed self-defense groups, which had typically been small and informal, began to evolve into more organized paramilitary groups that defended nonviolent protesters and openly challenged white violence. Palomo 2 Introduction On January 30, 1956, the home of Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. in Montgomery, Alabama had been bombed. Following this terrorist attack on his home, Dr. King applied for a permit to carry a concealed weapon at the sheriff's office. Although he had been denied the permit, Dr. King still kept fIrearms in his home. During his fIrst visit to King's home, journalist William Worth almost sat on two pistols while attempting to rest in an armchair. Accompanied by nonviolent activist Bayard Rustin, Worth was warned about the pistols on the chair. "Bill, wait, wait! Couple of guns on that chair! You don't want to shoot yourself." After nearly witnessing Worth shoot himself, Rustin questioned Dr. King on his possession of the two fIrearms. Dr. King succinctly responded: "Just for self-defense." This episode of armed self-defense was not an isolated event. -

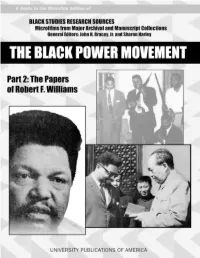

The Black Power Movement. Part 2, the Papers of Robert F

Cover: (Left) Robert F. Williams; (Upper right) from left: Edward S. “Pete” Williams, Robert F. Williams, John Herman Williams, and Dr. Albert E. Perry Jr. at an NAACP meeting in 1957, in Monroe, North Carolina; (Lower right) Mao Tse-tung presents Robert Williams with a “little red book.” All photos courtesy of John Herman Williams. A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 2: The Papers of Robert F. Williams Microfilmed from the Holdings of the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor Editorial Adviser Timothy B. Tyson Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of LexisNexis Academic & Library Solutions 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams [microform] / editorial adviser, Timothy B. Tyson ; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. 26 microfilm reels ; 35 mm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams. ISBN 1-55655-867-8 1. African Americans—Civil rights—History—20th century—Sources. 2. Black power—United States—History—20th century—Sources. 3. Black nationalism— United States—History—20th century—Sources. 4. Williams, Robert Franklin, 1925— Archives. I. Title: Papers of Robert F. Williams. -

Capitalism & Racism + Covid-19 = Murder

Struggle-La-Lucha.org Vol. 3, No. 7 · April 13, 2020 Suggested donation: $1 Twitter: @StruggleLaLucha Facebook.com/strugglelalucha email: [email protected] Capitalism & Racism BALTIMORE AMAZON Organizing to + Covid-19 = Murder defend workers’ By Stephen Millies (Figures for the different zip codes are updated every few hours at tinyurl.com/sp6gfv5) April 11 - The Covid-19 pandemic is devastat- All these neighborhoods are immigrant com- lives ing New York City. Eighty refrigerator trucks are munities with many service and construction serving as mobile morgues to store the bodies. workers who had to continue going to their jobs As of April 10, 92,384 people have been infected. while the pandemic was gripping the city. Inmates in the Rikers Island prison are being Black and Latinx neighborhoods in the offered $6 per hour to dig mass graves on Hart’s Bronx, Brooklyn and Manhattan have also been Island off the Bronx. That’s the site of Potter’s hard hit. The eastern Far Rockways in Queens, Field, where a million people too poor to afford home to four largely Black housing projects, a funeral had their bodies dumped. have 993 cases. By Sharon Black, What’s happening in New York City is be- The capitalist government is covering up the former Amazon worker ing repeated in Detroit, Chicago, New Orleans impact on Asian, Black, Indigenous and Latinx and Los Angeles. The coronavirus is ripping At the time of this writing, workers from eight communities. Maryland lawmakers are de- through the South with Black people suffering different Amazon warehouses have tested positive manding a breakdown of those who’ve caught the most. -

AUGUST 30, 2020 Happy Birthday

THIS WEEK IN BLACK HISTORY Mae Mallory Mae Mallory was an activist and freedom fighter who was at the forefront of some of the civil rights movement’s major events. Mallory was a founder of the Harlem Nine who railed against New York’s segregated school system and was a supporter of Black radical Robert F. Williams. Born June 9, 1927 in Macon, Georgia, Mallory moved to New York with her mother at the age of 12. In 1956, she became the founder and spokesperson for the Harlem Nine, a group of Black mothers who were critical of the poor conditions of Black schools and called for school integration. The Nine faced several legal hurdles, despite the federal ruling of “Brown v. Board of Education” and several attempts to jail them eventually failed. The efforts of the Nine included a successful lawsuit in 1960 which allowed thousands of parents to transfer their children to racially integrated schools. This came after help from the local NAACP and a 162-day boycott prior with leaders like Ella Baker and Adam Clayton Powell. Many of the first so-called “freedom schools” of the civil rights era were established as a result of the Nine’s work on the ground. 1959, Williams, who was also the leader of the Monroe, N.C. NAACP, befriended Mallory after a visit to New York. Mallory was taken with Williams’ message of self-defense and self-reliance and organized a group of supporters. By 1961, Mallory was aligned with Williams but they were met with resistance from white locals who feared a revolution. -

Post-Election Special Edition

posT-elecTion special issue The IndypendenT #219: deCeMBeR 2016 • IndypendenT.ORG IMMIGRAnTS FIGhT BACK, p6 CAn The deMOCRATS Be SAVed?, p12 hOW TO TALK TO yOUR KIdS ABOUT TRUMp, p16 And MORe... maePoe.Com 2 EDITOR’S NOTE THE INDYPENDENT THE INDYPENDENT, INC. LOVE & STRUGGLE 388 Atlantic Avenue, 2nd Floor Brooklyn, NY 11217 212-904-1282 www.indypendent.org e are facing the fi ght of our lives. It’s that fronts at the same time. Liberal opposition will likely Twitter: @TheIndypendent simple. be weak and inconsistent. We are going to lose a lot. facebook.com/TheIndypendent W Not that you would know it from listen- There will be people and places we love who will be ing to leading liberal politicians, media mavens and hurt and we won’t always be able to protect them, BOARD OF DIRECTORS: even labor leaders since Donald Trump won the elec- which will sting even more. Social movements will Ellen Davidson, Anna Gold, toral college and the presidency on Nov. 8. also fi ght back fi ercely and win victories that would Alina Mogilyanskaya, “If you succeed, the country succeeds,” President not seem possible. Ann Schneider, John Tarleton Obama told Trump when they chatted in front of re- One thing I learned from the Bush era is that we porters during his successor’s November 10 visit to will have to pace ourselves for the long haul to avoid the White House. In her concession speech Hillary demoralization and burnout. If there has been a sav- EDITOR: Clinton urged Americans to “keep an open mind,” ing grace since November 8, it is that these terrible John Tarleton about what Trump could accomplish as the 45th events have driven us toward each other in our fear president of the United States, even as his embold- and our vulnerability. -

Statements of Robert F. Williams

STATEMENTS OF ROBERT F. WILLIAMS HEARINGS (with subsequent staff interviews) BEFORE TH SUBCOM.1ITT1E.TO INVESTIGATE -THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE INTERNAL SECURITY ACT AND OTHER INTERNAL SECURITY LAWS, OF TUB COMMITTEE ON-THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE NINETY-FIRST CONGRESS SECOND SESSION PART 3 MARCH 25, 1970 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 45-159 WASHINGTON • 1971 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402. Price 60 cents S sA. /- COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JAMES 0. EASTLAND, Mississippi, Chairman JOHN L. McCLELLAN, Arkansas ROMAN L. HRUSKA, Nebraska SAM J. ERVIN, JR., North Calrolina HIRAM L. FONG, Hawaii THOMAS J." DODD, Connecticut HUGH SCOTT, Pennsylvania PHILIP A. HART, Michigan STROM THURMOND, South Carolina EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts MARLOW W. COOK, Kentucky BIRCH BAYH, Indiana CHARLES McC. MATHIAS, Jrt., Maryland QUENTIN N. BURDICK, North Dakota ROBERT P. GRIFFIN, Michigan JOSEPH D. TYDINGS, Maryland - ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia SUBCOMMITTEE To INVESTIGATE THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE INTERNAL SECURITY ACT AND OTHER INTERNAL SECURITY LAWS JAMES 0. EASTLAND, Mississippi, Chairman THOMAS J. DODD, Connecticut, Vice Chairman JOHN L. McCLELLAN, Arkansas HUGH SCOTT, Pennsylvania SAM J. ERVIN, JR., North Carolina STROM THURMOND, South Carolina BIRCH BAYH, Indiana MARLOW W. COOK, Kentucky ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ROBERT P. GRIFFIN, Michigan J. G. SOURWINE, Chief Counsel JOHN R. NORPEL, Directorof Research ALFONso L. TARABOCHIA, Chief Investigator RESOLUTION Resolved, by the Internal Security Subcommittee of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, that the attached Resolution relating to the citation of Robert F. -

Papers of the Naacp

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier PAPERS OF THE NAACP Supplement to Part 4, Voting Rights, General Office Files, 1956-1965 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier PAPERS OF THE NAACP Supplement to Part 4, Voting Rights, General Office Files, 1956-1965 Edited by John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier Project Coordinator Randolph Boehm Guide compiled by Blair D. Hydrick A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway * Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Papers of the NAACP. [microform] Accompanied by printed reel guides. Contents: pt. 1. Meetings of the Board of Directors, records of annual conferences, major speeches, and special reports, 1909-1950/editorial adviser, August Meier, edited by Mark Fox--pt. 2. Personal correspondence of selected NAACP officials, 1919-1939 / editorial--[etc.]--pt. 19. Youth File. 1. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People--Archives. 2. Afro-Americans--Civil Rights--History--20th century--Sources. 3. Afro- Americans--History--1877-1964--Sources. 4. United States--Race relations--Sources. I. Meier, August, 1923- . II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Title. E185.61 [Microfilm] 973'.0496073 86-892185 ISBN 1-55655-544-X (microfilm: Supplement to pt. 4) Copyright © 1995 by University Publications of America.