Robert F. Williams, Negroes with Guns, Ch. 3-5, 1962

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Locking up Our Own: James Forman Jr. in Conversation with Khalil Gibran Muhammad"

TRANSCRIPT "LOCKING UP OUR OWN: JAMES FORMAN JR. IN CONVERSATION WITH KHALIL GIBRAN MUHAMMAD" A conversation with James Forman, Jr. and Khalil Gibran Muhammad Introduction: Leonard Noisette Recorded May 8, 2017 ANNOUNCER: You are listening to a recording of the Open Society Foundations, working to build vibrant and tolerant democracies worldwide. Visit us at OpenSocietyFoundations.org. LEONARD NOISETTE: Good afternoon. Thanks to the Open Society fellowship program for pulling this event together. And thank you all for joining us. I'm Lenny Noisette. I oversee the criminal justice portfolio here in U.S. programs as-- as part of the Open Society Foundations. So I am particularly pleased to be able to kick off what I am sure will be an engaging and informative discussion with James Forman and Khalil-Gibran Muhammad about James's compelling new book, Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America. Just by way of instruction, James Forman Jr. is a professor of law at Yale Law School. He is a graduate of-- At-- Atlanta's Roosevelt High School, Brown University, and Yale Law School. And was a law clerk for Judge William Norris of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor of the United States Supreme Court. After clerking, James joined the Public Defender Service in Washington, D-- D.C., where for six years he represented both youth and adults charged with crimes. During his time as a public defender, James became frustrated with the lack of TRANSCRIPT: LOCKING UP OUR OWN: JAMES FORMAN JR. -

Olympic Charter

OLYMPIC CHARTER IN FORCE AS FROM 17 JULY 2020 OLYMPIC CHARTER IN FORCE AS FROM 17 JULY 2020 © International Olympic Committee Château de Vidy – C.P. 356 – CH-1007 Lausanne/Switzerland Tel. + 41 21 621 61 11 – Fax + 41 21 621 62 16 www.olympic.org Published by the International Olympic Committee – July 2020 All rights reserved. Printing by DidWeDo S.à.r.l., Lausanne, Switzerland Printed in Switzerland Table of Contents Abbreviations used within the Olympic Movement ...................................................................8 Introduction to the Olympic Charter............................................................................................9 Preamble ......................................................................................................................................10 Fundamental Principles of Olympism .......................................................................................11 Chapter 1 The Olympic Movement ............................................................................................. 15 1 Composition and general organisation of the Olympic Movement . 15 2 Mission and role of the IOC* ............................................................................................ 16 Bye-law to Rule 2 . 18 3 Recognition by the IOC .................................................................................................... 18 4 Olympic Congress* ........................................................................................................... 19 Bye-law to Rule 4 -

Black Women As Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools During the 1950S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Hostos Community College 2019 Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools during the 1950s Kristopher B. Burrell CUNY Hostos Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ho_pubs/93 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] £,\.PYoo~ ~ L ~oto' l'l CILOM ~t~ ~~:t '!Nll\O lit.ti t~ THESTRANGE CAREERS OfTHE JIMCROW NORTH Segregation and Struggle outside of the South EDITEDBY Brian Purnell ANOJeanne Theoharis, WITHKomozi Woodard CONTENTS '• ~I') Introduction. Histories of Racism and Resistance, Seen and Unseen: How and Why to Think about the Jim Crow North 1 Brian Purnelland Jeanne Theoharis 1. A Murder in Central Park: Racial Violence and the Crime NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS Wave in New York during the 1930s and 1940s ~ 43 New York www.nyupress.org Shannon King © 2019 by New York University 2. In the "Fabled Land of Make-Believe": Charlotta Bass and All rights reserved Jim Crow Los Angeles 67 References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or John S. Portlock changed since the manuscript was prepared. 3. Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in Names: Purnell, Brian, 1978- editor. -

Kwame Nkrumah, His Afro-American Network and the Pursuit of an African Personality

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-22-2019 Kwame Nkrumah, His Afro-American Network and the Pursuit of an African Personality Emmanuella Amoh Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the African History Commons Recommended Citation Amoh, Emmanuella, "Kwame Nkrumah, His Afro-American Network and the Pursuit of an African Personality" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 1067. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1067 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KWAME NKRUMAH, HIS AFRO-AMERICAN NETWORK AND THE PURSUIT OF AN AFRICAN PERSONALITY EMMANUELLA AMOH 105 Pages This thesis explores the pursuit of a new African personality in post-colonial Ghana by President Nkrumah and his African American network. I argue that Nkrumah’s engagement with African Americans in the pursuit of an African Personality transformed diaspora relations with Africa. It also seeks to explore Black women in this transnational history. Women are not perceived to be as mobile as men in transnationalism thereby underscoring their inputs in the construction of certain historical events. But through examining the lived experiences of Shirley Graham Du Bois and to an extent Maya Angelou and Pauli Murray in Ghana, the African American woman’s role in the building of Nkrumah’s Ghana will be explored in this thesis. -

Dayo Gore from Communist Politics to Black Power

Want to Start a Revolution? Gore, Dayo, Theoharis, Jeanne, Woodard, Komozi Published by NYU Press Gore, Dayo & Theoharis, Jeanne & Woodard, Komozi. Want to Start a Revolution? Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle. New York: NYU Press, 2009. Project MUSE., https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/10942 Access provided by The College Of Wooster (14 Jan 2019 17:20 GMT) 3 From Communist Politics to Black Power The Visionary Politics and Transnational Solidarities of Victoria “Vicki” Ama Garvin Dayo F. Gore As recounted in this collection’s introduction, when listing the key figures in Ghana’s expatriate community during the 1960s, writer Les- lie Lacy referenced Vicki Garvin, a longtime labor activist and black radi- cal, as one of the people to see “if you want to start a revolution.”1 While several recent studies on Black Power politics have acknowledged Vicki Garvin’s activism and transnational travels, she is often mentioned only as a representative figure, a “radical trade unionist,” or a “survivor of Mc- Carthyism,” with little attention given to the specific details of her life and political contributions.2 Yet Vicki Garvin played a leading role in the six decades of struggle that marked the shift from Negro civil rights to black liberation. Politicized in the upheavals of Depression-era Harlem and ac- tive in the U.S. left well into the 1980s, Garvin provides an important win- dow for understanding the significant channels of influence between the Old Left and the New Left and between black radicalism and the black freedom struggle. -

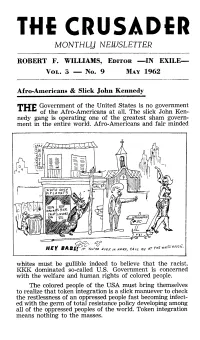

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

New Pathways in Civil Rights Historiography

Jeanne Theoharris, Komozi Woodard, eds.. Freedom North: Black Freedom Struggles Outside the South, 1940-1980. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001. vii + 326 pp. $26.95, paper, ISBN 978-0-312-29468-7. Reviewed by Patrick Jones Published on H-1960s (June, 2005) A few weeks into my "Civil Rights Movement" point. I want to contest my students' ready no‐ seminar, I place a series of images on the over‐ tions of the movement as they think they know it. head projector. One shows a long, inter-racial pro‐ Over the remainder of the semester, we set off on cession of movement activists marching down a an academic adventure to develop a more compli‐ street lined with modest homes, lifting signs and cated understanding of white supremacy and singing songs. Another depicts a sneering young struggles for racial justice. white man stretching a large confederate fag. Yet Admittedly, this brief exercise is a bit cheap another portrays three angry white men, faces and gimmicky, but the visual trickery conveys an contorted in rage, holding a crudely scrawled sign important point that is not soon lost on my stu‐ with the words "white power." I ask my students dents: most of us have been taught to accept, un‐ to scan these images for clues that might unlock critically, a certain narrative of the civil rights their meaning. Of course, they have seen such movement. This narrative focuses mainly on the photos before, from Montgomery and Little Rock, South and privileges well-known leaders, non-vio‐ Birmingham and Selma, and invariably it is these lent direct action, integration, and voting rights. -

KILLENS, JOHN OLIVER, 1916-1987. John Oliver Killens Papers, 1937-1987

KILLENS, JOHN OLIVER, 1916-1987. John Oliver Killens papers, 1937-1987 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Killens, John Oliver, 1916-1987. Title: John Oliver Killens papers, 1937-1987 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 957 Extent: 61.75 linear feet (127 boxes), 5 oversized papers boxes (OP), and 3 oversized bound volumes (OBV) Abstract: Papers of John Oliver Killens, African American novelist, essayist, screenwriter, and political activist, including correspondence, writings by Killens, writings by others, and printed material. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Series 5: Some student records are restricted until 2053. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Source Purchase, 2003 Citation [after identification of item(s)], John Oliver Killens papers, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Processing Processed by Elizabeth Roke, Elizabeth Stice, and Margaret Greaves, June 2011 This finding aid may include language that is offensive or harmful. Please refer to the Rose Library's harmful language statement for more information about why such language may appear and ongoing efforts to remediate racist, ableist, sexist, homophobic, euphemistic and other Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. John Oliver Killens papers, 1937-1987 Manuscript Collection No. 957 oppressive language. If you are concerned about language used in this finding aid, please contact us at [email protected]. -

Black Panthers Hold Forth at Camoius Pally , Identifies BARBARA AUTHIOR

Eldridge Cleaver FBI File #100-HQ-447251 Section 29 4* -:i-, Assoc. Dir. Dep. AD Adm. LAW OFFICES Dep. AD Iny. WALD, HARKRADER & ROSS Asst. Dir.: Adm. Serv. Ext. Affairs ROBERT L.WALD CARLETON A.HARKRADER WM.WARFIELD ROSS 910 SEVENTEEN THOMAS H. TRUITT ROBERT M. LICHTMAN STEPHEN B.IVESJR. Fin.& Pers. WASHINGTON, DONALD H. GREEN NEAL P. RUTLEDGE GEORGE A. AVERY THOMAS C. MATTHEWS, JR. THOMAS J.SCHWAB JOEL E. HOFFMAN Gen. Inv. (202) 87, TERRY F. LENZNER DANIEL F;O KEEFE,JR, DONALD T. BUCKLIN Ident. JERRY D.ANKER CHARLES C.ABELES ROBERT E. NAGLE CABLE ADORE ALEXANDER W.SIERCK TERRENCE ROCHE MURPHY WILLIAM R.WEISSMAN TELEX: 2 I ntell. STEPHEN M.TRUITT, TONI K.GOLDEN KEITH S.WATSON JAMES DOUGLAS WELCH ROBERT A. SKITOL STEVEN K.YABLONSKI SELMA M. LEVI] THOMAS W. BRUNNER C.COLEMAN BIRD GREER S. GOLDMAN Plan. & In GERALD B. WETLAUFER LEWIS M. POPPER MARK SCHATTNER OF COU Rec. RICHARD A. BROWN AVRUM M. GOLDBERG DENNIS D. CLARK Mgt. PHILIP I DAVID R. BERZ CAROL KINSBOURNE LESLIE S. BRETZ S.& T. Serve. ROBERT B. CORNELL DAVID B. WEINBERG ANTHONY L.YOUNG CHARLES F, ROBERT M.COHAN STEVEN M. GOTTLIEB STEVEN E. SILVERMAN Spec. Inv. NANCY H. HENDRY SHEILA JACKSON LEE + JAMES R. MYERS Training . GLORIA PHARES STEWART RANGELEY WALLACE * ON LEAVE Telephone Rm. Director's Sec'y February 14, 191 DELIVERED BY HAND FBI/DOJ OUTSIDE .,OLE ALL INFOTOTAT: CONTAIN Mr. Clarence M. Kelley HERMIN IS TN b Director DAT 09-11-2( U/P/EL b7C Federal Bureau of Investigation United States Department of Justice Washington, D.C. -

Gogo Vision What's Playing

GOGO VISION WHAT’S PLAYING CATALOG 183 MOVIES (100) TITLE TITLE NEW CONTENT Harriet A Star is Born Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets Sherlock Holmes Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 1 Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2 The Big Lebowski Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire The Breakfast Club Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince The Croods Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix Those Who Wish Me Dead Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban Addams Family, The (2019) Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone An American Pickle Horrible Bosses Batman Begins Horrible Bosses 2 Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice Impractical Jokers: The Movie Bill and Ted Face the Music Invisible Man, The Birds of Prey (And the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn) It's Complicated Blinded By The Light Joker Boogie Judas and the Black Messiah Coco Just Mercy Crazy Rich Asians Kajillionaire Crazy, Stupid, Love Let Them All Talk Die Hard Lilo and Stitch Disneys Upside-Down Magic Limbo Doctor Sleep Locked Down E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial Lucy in the Sky Elf Marvel Studios' Black Panther Emma Marvel Studios’ Avengers: Infinity War Finding Dory Marvel’s the Avengers: Age of Ultron Finding Nemo Minions Frozen 2 Mortal Kombat Godzilla v. Kong Mulan Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 My Spy Movies 1 TITLE News of the World The Dark Knight Nobody The Dark Knight Rises Nomadland The Kitchen Office Space The Lego Batman Movie Onward The Lego Movie Photograph, The The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part Queen & Slim -

Waveland, Mississippi, November 1964: Death of Sncc, Birth of Radicalism

WAVELAND, MISSISSIPPI, NOVEMBER 1964: DEATH OF SNCC, BIRTH OF RADICALISM University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire: History Department History 489: Research Seminar Professor Robert Gough Professor Selika Ducksworth – Lawton, Cooperating Professor Matthew Pronley University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire May 2008 Abstract: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced Snick) was a nonviolent direct action organization that participated in the civil rights movement in the 1960s. After the Freedom Summer, where hundreds of northern volunteers came to participate in voter registration drives among rural blacks, SNCC underwent internal upheaval. The upheaval was centered on the future direction of SNCC. Several staff meetings occurred in the fall of 1964, none more important than the staff retreat in Waveland, Mississippi, in November. Thirty-seven position papers were written before the retreat in order to reflect upon the question of future direction of the organization; however, along with answers about the future direction, these papers also outlined and foreshadowed future trends in radical thought. Most specifically, these trends include race relations within SNCC, which resulted in the emergence of black self-consciousness and an exodus of hundreds of white activists from SNCC. ii Table of Contents: Abstract ii Historiography 1 Introduction to Civil Rights and SNCC 5 Waveland Retreat 16 Position Papers – Racial Tensions 18 Time after Waveland – SNCC’s New Identity 26 Conclusion 29 Bibliography 32 iii Historiography Research can both answer questions and create them. Initially I discovered SNCC though Taylor Branch’s epic volumes on the Civil Right Movements in the 1960s. Further reading revealed the role of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced Snick) in the Civil Right Movement and opened the doors into an effective and controversial organization. -

Book Review the Black Police: Policing Our Own

BOOK REVIEW THE BLACK POLICE: POLICING OUR OWN LOCKING UP OUR OWN: CRIME AND PUNISHMENT IN BLACK AMERICA. By James Forman Jr. New York, N.Y.: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2017. Pp. 306. $27.00. Reviewed by Devon W. Carbado∗ & L. Song Richardson∗∗ INTRODUCTION Since Darren Wilson shot and killed Michael Brown in 2014,1 the problem of police violence against African Americans has been a rela- tively salient feature of nationwide discussions about race. Across the ideological spectrum, people have had to engage the question of whether, especially in the context of policing, it’s fair to say that black lives are undervalued. While there is both a racial and a political divide with respect to how Americans have thus far answered that question, the emergence of Black Lives Matter movements2 has made it virtually im- possible to be a bystander in the debate. Separate from whether racialized policing against African Americans is, in fact, a social phenomenon, is the contestable question about solu- tions: Assuming that African Americans are indeed the victims of over- policing, meaning that by some metric they end up having more inter- actions with the police and more violent encounters than is normatively warranted, what can we do about it? And here, the answers range from abolishing police officers altogether, to training them, to diversifying po- lice departments. It is on the last of these proposed solutions — the diversification of police departments — that we focus in this essay. The central question we ask is: What are the dynamics that might shape how African American police officers police other African Americans? Asked another way, what do existing theories about race and race relations, ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ∗ Associate Vice Chancellor of BruinX for Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, the Honorable Harry Pregerson Professor of Law, University of California, Los Angeles School of Law.