CMA CGM Florida and Chou Shan Should Pass Port-To-Port

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Coast of South America

PUB. 124 SAILING DIRECTIONS (ENROUTE) ★ EAST COAST OF SOUTH AMERICA ★ Prepared and published by the NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY Bethesda, Maryland © COPYRIGHT 2004 BY THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT NO COPYRIGHT CLAIMED UNDER TITLE 17 U.S.C. 2004 NINTH EDITION For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: http://bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 Preface 0.0 Pub. 124, Sailing Directions (Enroute) East Coast of South 0.0 Dangers.—As a rule outer dangers are fully described, but America, Ninth Edition, 2004, is issued for use in conjunction inner dangers which are well-charted are, for the most part, with Pub. 160, Sailing Directions (Planning Guide) South omitted. Numerous offshore dangers, grouped together, are Atlantic Ocean and Indian Ocean. The companion volume is mentioned only in general terms. Dangers adjacent to a coastal Pub. 123. passage or fairway are described. 0.0 This publication has been corrected to 28 February 2004, 0.0 Distances.—Distances are expressed in nautical miles of 1 including Notice to Mariners No. 9 of 2004. minute of latitude. Distances of less than 1 mile are expressed in meters, or tenths of miles. Explanatory Remarks 0.0 Geographic Names.—Geographic names are generally those used by the nation having sovereignty. Names in paren- 0.0 Sailing Directions are published by the National Geospatial- theses following another name are alternate names that may Intelligence Agency (NGA), under the authority of Department appear on some charts. -

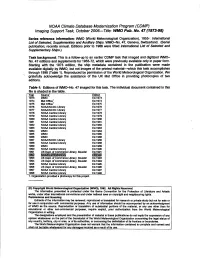

NOAA Climate Database Modernization Program (CD MP

NOAA Climate Database Modernization Program (CDMP) Imaging Support Task, October 2006--Title: WOPub. No. 47 (1973-98) Series reference information: WMO (World Meteorological Organization), 1955: lnfernafional Lisf of Selected, Supplementary and Auxiliary Ships. WMO-No. 47, Geneva, Switzerland. (Serial publication; recently annual. Editions prior to 1966 were titled lnfernafional List of Selecfed and Supplementary Ships.) Task background: This is a follow-up to an earlier CDMP task that imaged and digitized WMO- No. 47 editions and supplements for 1955-72, which were previously available only in paper form. Starting with the 1973 edition, the ship metadata contained in the publication were made available digitally by WMO, but not images of the printed material-which this task accomplishes through 1998 (Table 1). Reproduced by permission of the World Meteorological Organization. We giatefully acknowledge the assistance of the UK Met Office in providing photocopies of two editions. Table f: Editions of WMO-No. 47 imaged for this task. The individual document contained in this file is shaded in the table. -Year Source' Edition 1973 WMO Ed. 1973 1974 Metoffice' Ed. 1974 1975 Metoffice' Ed. 1975 1976 NOMNCDC Library Ed. 1976 I977 NOMNCDC Library Ed.1977 1978 NOMCentral Library Ed. 1978 1979 NOMCentral Library Ed. 1979 1980 NOMCentral Library Ed. 1980 1981 NOAA Central Library Ed.1981 1982 NOMCentral Library Ed. I982 1983 NOAA Central Library Ed.1983 1984 WMO Ed. I984 1985 WMO Ed.1985 1986 WMO Ed. 1986 1987 NOMNCDC Library Ed.1 986 1988 NOAA Central Library Ed.1988 1989 WMO Ed.1989 1990 NOAA Central Libraw Ed.1990 1991 u e Library, Boulder Ed.1991 %@E 1 EX9Z 1993 US Dept: of.Commerce Library, Boulder Ed.1993 1994 US Dew. -

North Europe East Med Service

BORCHARD LINES LTD STATUS 06/20 10 Chiswell Street, London EC1Y 4XY BOR/F66 Telephone: 020 7628 6961 SAILING SCHEDULE NO. 40 DATE: 29th Sep 2021 L R A L A A H M L R A O O N I S L A E O O N NORTH EUROPE N T T M H E I R N T T D T W A D X F S D T W EAST MED O E E S O A A I O E E SERVICE N R R S D N N N R R D P O D D P A L R A M I M A IMO Number / ICS VESSEL VOYAGE Entry Key IMO: 9283203 MPAS135N MONTE PASCOAL 12/8 14/8 22/8 1/9 2/9 4/9 (2/9) 9/9 22/9 29/9 4/10 ICS: 26/09/21 132S / 135N IMO: 9283186 MCER136N MONTE CERVANTES 19/8 21/8 29/8 8/9 9/9 11/9 14/9 16/9 30/9 3/10 9/10 ICS: 03/10/21 133S / 136N IMO: 9283198 MOLI137N MONTE OLIVIA 27/8 28/8 4/9 15/9 (21/9) 18/9 21/9 23/9 6/10 9/10 16/10 ICS: 10/10/21 134S / 137N IMO: 9244934 MKIG138N MAERSK KINGSTON 2/9 3/9 14/9 22/9 23/9 25/9 28/9 30/9 (13/10) (15/10) (23/10) ICS: 17/10/21 135S / 138N IMO: 9348065 MALE139N MONTE ALEGRE 10/9 10/9 21/9 29/9 30/9 2/10 - - 15/10 16/10 23/10 ICS: 24/10/21 136S / 139N IMO: 9283239 MVER140N MONTE VERDE 16/9 19/9 28/9 6/10 7/10 9/10 - - 22/10 23/10 30/10 ICS: 31/10/21 137S / 140N IMO: 9283203 MPAS141N MONTE PASCOAL 22/9 29/9 4/10 13/10 14/10 16/10 - - 29/10 30/10 6/11 ICS: 07/11/21 138S / 141N IMO: 9283186 MCER142N MONTE CERVANTES 30/9 3/10 9/10 20/10 21/10 23/10 - - 5/11 6/11 13/11 ICS: 14/11/21 139S / 142N IMO: 9283198 MOLI143N MONTE OLIVIA 6/10 9/10 16/10 27/10 28/10 30/10 - - 12/11 13/11 20/11 ICS: 21/11/21 140S / 143N IMO: 9348065 MALE144N MONTE ALEGRE 15/10 16/10 23/10 3/11 4/11 6/11 - - 19/11 19/11 27/11 ICS: 28/11/21 141S / 144N IMO: 9283239 MVER145N MONTE VERDE 29/10 30/10 7/11 10/11 11/11 13/11 - - 25/11 26/11 4/12 ICS: 05/12/21 143S / 145N IMO: 9283203 MPAS146N MONTE PASCOAL 5/11 6/11 14/11 17/11 18/11 20/11 - - 2/12 3/12 11/12 ICS: 12/12/21 144S / 146N Please Note: Vessel IMO Number and ICS Entry Key to be used for EU Import Control System. -

LEICESTERS UNKNOWN SOLDIER Our Unknown Soldier

was the battered shoulder title: LEICESTER. No effort was spared to identify the soldier. The Ministry of Defence, the Regiment and the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland (where the Regiment’s archives are housed) were all contacted. Was the Unknown Soldier from the 4th Battalion (recruited in Leicester and its suburbs) or the 5th (County) Battalion? Was there anything amongst the remains with a name or number? LEICESTERS UNKNOWN SOLDIER Sadly, it proved impossible to identify the unknown ‘Tiger’. Although a I received from Ken Roberts Secretary treasure trove of buttons, buckles and of East Midlands RAMC Association personal items (from a mug and spoon Branch the following which I thought to the coins in his pocket) were would be of interest to members. unearthed, none gave any clue as to identity. There was no identity disk, no Our Unknown Soldier inscribed watch or cigarette case, and no personal papers had survived in the On 20 February 2016 the remains of a wet earth. British soldier of the Great War were unearthed near the French town of Thanks to the kindness of the Royal Auchy-les-Mines by members of The Tigers Association the Record Office is Durand Group, a team researching the now able to put on display some of the underground relics – dugouts, tunnels artefacts found beside that Unknown and mines – of the First World War. At Soldier of our County Regiment. Auchy, the Durand archaeologists Alongside a display on the battle, were exploring an entrance to the once visitors can see personal relics and fearsome German fortress, the rusted pieces of equipment from that Hohenzollern Redoubt. -

Daily Shipping Newsletter 2004 – 197 Vlierodam Wire

DAILY SHIPPING NEWSLETTER 2004 – 197 Number 197***DAILY SHIPPING NEWSLETTER***Tuesday 05-10-2004 THIS NEWSLETTER IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY : VLIERODAM WIRE ROPES Ltd. wire ropes, chains, hooks, shackles, webbing slings, lifting beams, crane blocks, turnbuckles etc. Binnenbaan 36 3161VB RHOON The Netherlands Telephone: (+31)105018000 (+31) 105015440 (a.o.h.) Fax : (+31)105013843 Internet & E-mail www.vlierodam.nl [email protected] The new Hoek van Holland lifeboat JANINE PARQUI under construction Photo : Jerry Bezuijen © PSi-Daily Shipping News Page 1 10/4/2004 DAILY SHIPPING NEWSLETTER 2004 – 197 EVENTS, INCIDENTS & OPERATIONS World´s largest containership CSCL EUROPE seen here departing from Rotterdam with 24 hours delay due to the strike of the dockworkers at the Delta Terminal Photo : Hans de Jong – Maritime pictures © Fatigue risks too great Following the release of accident investigation reports into two groundings in the Marlborough Sounds this year the Maritime Safety Authority has called for boat owners, operators and crew to pay more attention to the issue of fatigue. The grounding of the Kathleen G in May and the Physalie in June both resulted from skippers falling asleep due to fatigue. “Fortunately no-one was injured in these accidents but our research shows fifty percent of seafarers were fatigued on at least one of their last five trips and already this year there have been five accidents where fatigue has been a major contributing factor,” says MSA Manager Strategic Analysis and Planning Sharyn Forsyth. “The fishing industry by nature has a highly demanding physical workload but not managing fatigue properly is clearly too great a risk to take. -

IVI5 Oceanía Barcos.Pdf

COORDINACIÓN GENERAL DE PUERTOS Y MARINA MERCANTE DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE MARINA MERCANTE OCEANÍA REPORTADOS EN OPERACIÓN EN 2013 PAÍS BARCO BANDERA TIPO DE BARCO TRB AUSTRALIA MAPLE INGRID ANT. Y BAR. CARGA GENERAL 9,585 AGIA COREA DEL SUR GRANELERO 26,092 ALAM AMAN II MALASIA GRANELERO 27,306 ARIETTA MALTA GRANELERO 22,400 BEKS HALIL MARSHALL I. GRANELERO 33,277 BULK JAPAN PANAMÁ GRANELERO 42,887 C. QUEEN COREA DEL SUR GRANELERO 77,697 CARAVOS LIBERTY MARSHALL I. GRANELERO 35,812 CHANG SHAN HAI PANAMÁ GRANELERO 33,044 CHOULEX GRAN BRETAÑA GRANELERO 77,211 CIELO DI PALERMO PANAMÁ GRANELERO 22,866 DENSA CHEETAH MALTA GRANELERO 22,709 GREEN PHOENIX PANAMÁ GRANELERO 31,763 IKAN SELAYANG PANAMÁ GRANELERO 31,775 BARCOS MOSOR CROACIA GRANELERO 24,533 NAVIOS SERENITY LIBERIA GRANELERO 23,448 PACIFIC PRIDE PANAMÁ GRANELERO 35,297 PANOCEANIS GRECIA GRANELERO 29,953 THORCO GALAXY CHINA GRANELERO 10,021 WESTERN CARMEN CHIPRE GRANELERO 22,668 WESTERN LUCREZIA CHIPRE GRANELERO 45,670 ZHE HAI 505 CHINA GRANELERO 22,295 ACAPULCO SINGAPUR PORTA CONTENEDOR 10,730 ALIANCA ITAPOA CHINA PORTA CONTENEDOR 91,051 ANGOL LIBERIA PORTA CONTENEDOR 32,901 APL CANADA LIBERIA PORTA CONTENEDOR 65,792 ANUARIO ESTADÍSTICO DEL TRANSPORTE MARÍTIMO 2013 COORDINACIÓN GENERAL DE PUERTOS Y MARINA MERCANTE DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE MARINA MERCANTE OCEANÍA REPORTADOS EN OPERACIÓN EN 2013 PAÍS BARCO BANDERA TIPO DE BARCO TRB AUSTRALIA APL ENGLAND SINGAPUR PORTA CONTENEDOR 65,792 APL HAMBURG CHINA PORTA CONTENEDOR 71,786 APL HOLLAND SINGAPUR PORTA CONTENEDOR 65,792 APL INDIA LIBERIA PORTA CONTENEDOR 65,792 APL LONDON GRAN BRETAÑA PORTA CONTENEDOR 71,786 APL NORWAY LIBERIA PORTA CONTENEDOR 71,867 APL OREGON SINGAPUR PORTA CONTENEDOR 71,787 APL ROTTERDAM CHINA PORTA CONTENEDOR 71,786 APL SCOTLAND SINGAPUR PORTA CONTENEDOR 65,792 APL TOKYO GRAN BRETAÑA PORTA CONTENEDOR 71,786 ATLANTA EXPRESS ALEMANIA PORTA CONTENEDOR 58,833 BANGKOK EXPRESS ALEMANIA PORTA CONTENEDOR 75,590 BELLAVIA MARSHALL I. -

Violence Against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil 2014 DATA

REPORT REPORT – VIOLENCE AGAINST INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN BRAZIL – 2014 DATA 2014 – BRAZIL IN PEOPLES INDIGENOUS AGAINST VIOLENCE – REPORT Violence against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil 2014 DATA REPORT Violence against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil 2014 DATA This publication was supported by Rosa Luxemburg Foundation with funds from the Federal Ministry for Economic and German Development Cooperation (BMZ). Support This report is a publication by the Missionary Council for Indigenous Peoples (Conselho Indigenista Missionário – Cimi), under the umbrella of the National Conference of Bishops of Brasil (Conferência Nacional dos Bispos do Brasil – CNBB) PRESIDENT D. Erwin Kräutler SDS Edifício Venâncio III, salas 309 a 314 Brasília-DF – Brasil – Cep 70.393-902 Phone: 55 61 21061650 www.cimi.org.br REPORT Violence against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil – 2014 Data ISBN 978-85-87433-08-4 RESEARCH COORDINATION Lúcia Helena Rangel – Professor of Anthropology at PUC-SP RESEARCH AND DATA COLLECTION Cimi Regional Branches and the Cimi Documentation Office ORGANIZATION OF DATA TABLES Eduardo Holanda, Leda Bosi and Marluce Ângelo da Silva REVISION OF DATA TABLES Lúcia Helena Rangel and Roberto Antonio Liebgott IMAGE SELECTION Aida Cruz EDITING Patrícia Bonilha ENGLISH VERSION Maíra Mendes Galvão DESKTOP PUBLISHING Licurgo S. Botelho BOOK COVER During a demonstration against the demarcation of the Araçaí Indigenous Lands by the Guarani people, farmers planted several crosses on the road that leads to their lands, in the municipality of Cunha Porã (SC) to intimidate the natives. Photo: Jacson Santana We dedicate this publication to our greater brother Fr. Iasi Junior who passionately dedicated himself for almost half a century to the cause of the indigenous peoples and the implacable denouncement of violence against them and violations of their rights in Brazil. -

Missionary Council for Indigenous Peoples

ReportReport onon ViolenceViolence AgainstAgainst IndigenousIndigenous PeoplesPeoples inin BrazilBrazil 20192019 DATADATA Report on Violence Against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil 2019 DATA SUPPORT is report is published by the Indigenist Missionary Council (Conselho Indigenista Missionário - CIMI), an entity linked to the National Conference of Brazilian Bishops (Conferência Nacional dos Bispos do Brasil - CNBB) www.cimi.org.br PRESIDENT Don Roque Paloschi VICE PRESIDENT Lúcia Gianesini EXECUTIVE SECRETARY Antônio Eduardo C. Oliveira ASSISTANT SECRETARY Cleber César Buzatto Report on Violence Against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil – 2019 Data 1984-7645 ISS N RESEARCH COORDINATION Lucia Helena Rangel RESEARCH AND DATA SURVEY CIMI Regional Offices and CIMI Documentation Sector ORGANIZATION OF DATA TABLES Eduardo Holanda and Leda Bosi REVIEW OF DATA TABLES Lucia Helena Rangel and Roberto Antonio Liebgott IMAGE SELECTION Aida Cruz EDITORIAL COORDINATION Patrícia Bonilha LAYO U T Licurgo S. Botelho COVER In August 2019, farmers occupying part of the Valparaiso Indigenous Land, which was claimed by the Apurinã people 29 years ago, burned 600 of the approximately 27,000 hectares of the area located in the municipality of Boca do Acre, in southern part of the state of Amazonas. Among other serious losses, the fire destroyed a chestnut plantation used by the indigenous community as a source of livelihood Photo: Denisa Sterbova is issue of the Report on Violence Against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil –2019 Data is dedicated to all the victims of indigenous rights violations, as well as to those engaged in the fight for life, in particular the Prophet, Confessor and Poet Pedro Casaldáliga (1928-2020). Since CIMI was established, Pedro has taught us to: Be the water that flows through the stones and Jump off the inherited iron rails, Trade a career for the Path in the ministry of the Kingdom, Go out into the world to establish peace built on the foundations of justice and solidarity. -

Longo Curso Sentido Norte ABUS - TANGO BRIOA Deadline Nome Do Navio Sigla Viagem ETA ETB ETS Terminal Carga Draft Observações

Daily Position ITAJAÍ Date: 09/09/2018 Time: 10:20:03 PM Longo curso sentido Norte ABUS - TANGO BRIOA Deadline Nome do Navio Sigla Viagem ETA ETB ETS Terminal Carga Draft Observações ITAPOA TERMINAIS MONTE TAMARO MOTAM 089 30/08/18 17:51 30/08/18 17:51 31/08/18 16:03 PORTUARIOS S/A 29/08/18 18:00 27/08/18 08:00 ITAPOA TERMINAIS CAP ANDREAS CANAS 029 07/09/18 06:00 07/09/18 07:00 08/09/18 02:00 PORTUARIOS S/A 05/09/18 18:00 03/09/18 08:00 ITAPOA TERMINAIS RIO BARROW RIBAR 006 13/09/18 16:00 13/09/18 18:00 14/09/18 17:00 PORTUARIOS S/A 12/09/18 18:00 10/09/18 08:00 ITAPOA TERMINAIS SAFMARINE MAFADI SAMAF 089 20/09/18 17:00 20/09/18 19:00 21/09/18 16:00 PORTUARIOS S/A 19/09/18 18:00 17/09/18 08:00 ITAPOA TERMINAIS E.R. BERLIN ERBER 002 27/09/18 17:00 27/09/18 19:00 28/09/18 16:00 PORTUARIOS S/A 26/09/18 18:00 24/09/18 08:00 ITAPOA TERMINAIS MONTE ACONCAGUA MONAC 084 04/10/18 17:00 04/10/18 19:00 05/10/18 16:00 PORTUARIOS S/A 03/10/18 18:00 01/10/18 08:00 ITAPOA TERMINAIS MONTE ROSA MOROS 081 11/10/18 17:00 11/10/18 19:00 12/10/18 16:00 PORTUARIOS S/A 10/10/18 18:00 08/10/18 08:00 ITAPOA TERMINAIS MONTE TAMARO MOTAM 090 18/10/18 17:00 18/10/18 19:00 19/10/18 16:00 PORTUARIOS S/A 17/10/18 18:00 15/10/18 08:00 ITAPOA TERMINAIS CAP ANDREAS CANAS 030 25/10/18 17:00 25/10/18 19:00 26/10/18 16:00 PORTUARIOS S/A 24/10/18 18:00 22/10/18 08:00 ITAPOA TERMINAIS RIO BARROW RIBAR 007 01/11/18 17:00 01/11/18 19:00 02/11/18 16:00 PORTUARIOS S/A 31/10/18 18:00 29/10/18 18:00 SAEC - BOSSA NOVA BRITJ Deadline Nome do Navio Sigla Viagem ETA ETB ETS Terminal -

N4 - BCT Vessel Services

N4 - BCT Vessel Services Service Service Lead Part Flexi Mty Swings Agent Vessels Stevedore Allocated Number Name Line Lines Trac Cont. Space 102 HLC HLC ALI TRAC IMS PHA KNS Conti Darwin (CTD), E.R. Berlin (ERB), TSS 3D,3E (GS1) HLC TRAC IMS PHA E.R. Canada (ERC), E.R. Seoul (CHN), Malleco (MCO) 4D,4E HSD GCCP PHA PHA Rhodos (RDS), Skiathos (SKS), UASC Bubiyan (BUB) MSC MAE MSC Barcelona (MCB) HT NYC ZIM Note: vessels in purple are 17 containers wide HLC: GULF E/COAST S. AMERICA Note: Vessels in red are 16 containers wide Monday 104 HLC HLC CMA GCCP IMS PHA KNS Allegoria (ALG), Brussels (BRU), TSS 5D,5E (GM8) HLC GCCP IMS PHA Chacabuco, (CBO), Santa Vanessa (VAN), S Santiago (SGO) 6D,6E HSD GCCP IMS PHA Venetiko (VEO), Vermont Trader (VTR) MAE GCCP IMS PHA ZIM GCCP IMS PHA HLC: GULF MED SERVICE Note: Vessels in red are 16 containers wide Wednesday 105A HLC HLC ACL IMS PHA KNS Charleston Express (CNE), Ceres 1E (AX3) APL IMS PHA Philadelphia Express (PES), St. Louis Express (SLE), 2E HLC TRAC PHA Washington Express (WNE), Yorktown Express (YNE) OOC PHA PHA HLC: AL3 Note: U.S. flag vessels Tuesday 106A HLC Aegiali (AEG), Genoa (GEN), Ceres 3B,3C March (MRC), Rio Blackwater (RBW), 4B,4C ONL MOL Glide (GLI), MOL Grattitude (GAT) AL4 Note: Vessels in red are 16 containers wide. Friday 109 HSD HSD ALI GCCP IMS PHA KNS Monte Pascoal (MTP), Monte Verde (MTV) TSS 1C,1D, (SCS) HLC TRAC IMS PHA Monte Cervantes (MOE), Monte Olivia (MTO), Monte Sarmiento (MOS) 2C,2D MSC HSD GCCP IMS PHA MSC Michaela (MML), MSC Oriane (MOR) HT MSC GCCP IMS PHA SOUTH AMERICA ZIM Note: Vessels in red are 16 containers wide. -

LCSH Section N

N-(3-trifluoromethylphenyl)piperazine Na Guardis Island (Spain) Naassenes USE Trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine USE Guardia Island (Spain) [BT1437] N-3 fatty acids Na Hang Nature Reserve (Vietnam) BT Gnosticism USE Omega-3 fatty acids USE Khu bảo tồn thiên nhiên Nà Hang (Vietnam) Nāatas N-6 fatty acids Na-hsi (Chinese people) USE Navayats USE Omega-6 fatty acids USE Naxi (Chinese people) Naath (African people) N.113 (Jet fighter plane) Na-hsi language USE Nuer (African people) USE Scimitar (Jet fighter plane) USE Naxi language Naath language N.A.M.A. (Native American Music Awards) Na Ih Es (Apache rite) USE Nuer language USE Native American Music Awards USE Changing Woman Ceremony (Apache rite) Naaude language N-acetylhomotaurine Na-Kara language USE Ayiwo language USE Acamprosate USE Nakara language Nab River (Germany) N Bar N Ranch (Mont.) Na-khi (Chinese people) USE Naab River (Germany) BT Ranches—Montana USE Naxi (Chinese people) Nabā, Jabal (Jordan) N Bar Ranch (Mont.) Na-khi language USE Nebo, Mount (Jordan) BT Ranches—Montana USE Naxi language Naba Kalebar Festival N-benzylpiperazine Na language USE Naba Kalebar Yatra USE Benzylpiperazine USE Sara Kaba Náà language Naba Kalebar Yatra (May Subd Geog) n-body problem Na-len-dra-pa (Sect) (May Subd Geog) UF Naba Kalebar Festival USE Many-body problem [BQ7675] BT Fasts and feasts—Hinduism N-butyl methacrylate UF Na-lendra-pa (Sect) Naba language USE Butyl methacrylate Nalendrapa (Sect) USE Nabak language N-carboxy-aminoacid-anhydrides BT Buddhist sects Nabagraha (Hindu deity) (Not Subd Geog) USE Amino acid anhydrides Sa-skya-pa (Sect) [BL1225.N38-BL1225.N384] N-cars Na-lendra-pa (Sect) BT Hindu gods USE General Motors N-cars USE Na-len-dra-pa (Sect) Nabak language (May Subd Geog) N Class (Destroyers) (Not Subd Geog) Na Maighdeanacha (Northern Ireland) UF Naba language BT Destroyers (Warships) USE Maidens, The (Northern Ireland) Wain language N. -

Ships Insured Between 20Th Feb 2011 & 20Th February 2012

UK P&I Club - Ships insured between 20th February 2011 & 20th February 2012 SHIP NAME IMO NUMBER AET EXCELLENCE 9632595 A LA MARINE 9386524 AET EXPLORER 7318963 AARGAU 9583897 AET HARRIS 7318963 AARTI PREM 9087738 AET INNOVATOR 9632583 AASHMAN 8323719 AET LIBERTY 7807603 ABADI 9210828 AET NUECES 8115710 ABAKAN 8711277 AET PIONEER 7923500 ABDELKADER 9360922 AET SHELBY UNKNOWN ABERDEEN 9125736 AETOLIA 9425813 ACAVUS 9308754 AFOGNAK UNKNOWN ACHATINA 9308766 AFRICAN BEGONIA 7812464 ACHILLEAS 9458494 AFRICAN DAHLIA 8005721 ACHILLES II 9269001 AFRICAN FERN 8014954 ACX DIAMOND 9360609 AFRICAN IRIS 7801324 ACX LILY 8914271 AGATE V 9424534 ACX MARGUERITE 9163441 AGATHONISSOS 9232448 ACX PEARL 9360623 AGATIS 9117844 ADAM E.CORNELIUS 7326245 AGHIA MARINA 9087805 ADELINA D 9306079 AIGAION 9268473 ADMIRAL MAKAROV 7347603 AILA 9354337 ADVENTURE 9286073 AIRSNIPE UNKNOWN AEGEA 9379612 AKADEMIK GOLITSYN 8119003 AEGEAN LEADER 9054119 AKAMAS 9018414 AEGEAS 9315800 AKIJ GLORY 8413253 AEOLIAN HERITAGE 9483542 AKIJ WAVE 9109366 AEOLIAN VISION 9483554 AKRI 9520261 AET DISCOVERY 7645732 AKTEA 9291236 AET ENDEAVOUR 7723637 AL AAMRIYA 9338266 Ships entered in the Club may not be on risk for the whole of the policy year in question. Enquiries regarding this register should be made to John McPhail, Compliance Officer, UK P&I Club, Tel: +44 20 7204 2308; Email: [email protected] 1/64 UK P&I Club - Ships insured between 20th February 2011 & 20th February 2012 AL BADIYAH 8619443 ALBION BAY 9496989 AL DEEBEL 9307176 ALBORAN 9206700 AL DEERAH 8619455 ALCEDO