A Structural Analysis of Constantin Brancusi's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Approval of Minutes: Election of Officers: Sarah

BAKER CITY PUBLIC ARTS COMMISSION APPROVED MINUTES July 9, 2019 ROLL CALL: The meeting was called to order at 5:40 p.m. Present were: Ann Mehaffy, Lynette Perry, Corrine Vetger, Kate Reid, Fred Warner, Jr., Robin Nudd and guest Dean Reganess. APPROVAL OF Lynette moved to approve the June minutes as presented. Corrine MINUTES: seconded the motion. Motion carried. ELECTION OF Ann questioned if she and Corrine could serve as co-chairs. Robin OFFICERS: would check into it and let them know at next meeting. SARAH FRY PROJECT Ann reported that the pieces were being stored in the basement at UPDATE: City Hall. Ann would check with Molly to see if she had heard back on timeline for repairs to brickwork at the Corner Brick building. ART ON LOAN: Corrine stated that she would reach out to Shawn. SHAWN PETERSON PROJECT UPDATE: VINYL WRAP Nothing new to report on the project with ODOT. UPDATE: OTHER BUSINESS: Dean Reganess was present and visited with group regarding his trade: stone masonry. Dean is a third generation stone mason and had recently relocated to Baker City. Dean announced that he wanted to offer his help in the community and discussed creating a large community stone sculpture that could be pinned together. Dean also discussed stone benches with an estimated cost of $1200/each. Dean mentioned that a film crew would be coming from San Antonio and thought the exposure might be good for Baker. Corrine questioned if Dean had ideas to help the Public Arts Commission raise funds for public art. Dean mentioned that he would be willing to create a mold/casting of something that depicted Baker and it could be recreated and sold to raise funds. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/28/2021 10:23:11PM Via Free Access Notes to Chapter 1 671

Notes 1 Introduction. Fall and Redemption: The Divine Artist 1 Émile Verhaeren, “La place de James Ensor Michelangelo, 3: 1386–98; Summers, Michelangelo dans l’art contemporain,” in Verhaeren, James and the Language of Art, 238–39. Ensor, 98: “À toutes les périodes de l’histoire, 11 Sulzberger, “Les modèles italiens,” 257–64. ces influences de peuple à peuple et d’école à 12 Siena, Church of the Carmines, oil on panel, école se sont produites. Jadis l’Italie dominait 348 × 225 cm; Sanminiatelli, Domenico profondément les Floris, les Vaenius et les de Vos. Beccafumi, 101–02, no. 43. Tous pourtant ont trouvé place chez nous, dans 13 E.g., Bhabha, Location of Culture; Burke, Cultural notre école septentrionale. Plus tard, Pierre- Hybridity; Burke, Hybrid Renaissance; Canclini, Paul Rubens s’en fut à son tour là-bas; il revint Hybrid Cultures; Spivak, An Aesthetic Education. italianisé, mais ce fut pour renouveler tout l’art See also the overview of Mabardi, “Encounters of flamand.” a Heterogeneous Kind,” 1–20. 2 For an overview of scholarship on the painting, 14 Kim, The Traveling Artist, 48, 133–35; Payne, see the entry by Carl Van de Velde in Fabri and “Mescolare,” 273–94. Van Hout, From Quinten Metsys, 99–104, no. 3. 15 In fact, Vasari also uses the term pejoratively to The church received cathedral status in 1559, as refer to German art (opera tedesca) and to “bar- discussed in Chapter Nine. barous” art that appears to be a bad assemblage 3 Silver, The Paintings of Quinten Massys, 204–05, of components; see Payne, “Mescolare,” 290–91. -

Sculpture Northwest Nov/Dec 2015 Ssociation a Nside: I “Conversations” Why Do You Carve? Barbara Davidson Bill Weissinger Doug Wiltshire Victor Picou Culptors

Sculpture NorthWest Nov/Dec 2015 ssociation A nside: I “Conversations” Why Do You Carve? Barbara Davidson Bill Weissinger Doug Wiltshire Victor Picou culptors S Stone Carving Videos “Threshold” Public Art by: Brian Goldbloom tone S est W t Brian Goldbloom: orth ‘Threshold’ (Detail, one of four Vine Maple column wraps), 8 feet high and 14 N inches thick, Granite Sculpture NorthWest is published every two months by NWSSA, NorthWest Stone Sculptors Association, a In This Issue Washington State Non-Profit Professional Organization. Letter From The President ... 3 CONTACT P.O. Box 27364 • Seattle, WA 98165-1864 FAX: (206) 523-9280 Letter From The Editors ... 3 Website: www.nwssa.org General e-mail: [email protected] “Conversations”: Why Do We Carve? ... 4 NWSSA BOARD OFFICERS Carl Nelson, President, (425) 252-6812 Ken Barnes, Vice President, (206) 328-5888 Michael Yeaman, Treasurer, (360) 376-7004 Verena Schwippert, Secretary, (360) 435-8849 NWSSA BOARD Pat Barton, (425) 643-0756 Rick Johnson, (360) 379-9498 Ben Mefford, (425) 943-0215 Steve Sandry, (425) 830-1552 Doug Wiltshire, (503) 890-0749 PRODUCTION STAFF Penelope Crittenden, Co-editor, (541) 324-8375 Lane Tompkins, Co-editor, (360) 320-8597 Stone Carving Videos ... 6 DESIGNER AND PRINTER Nannette Davis of QIVU Graphics, (425) 485-5570 WEBMASTER Carl Nelson [email protected] 425-252-6812 Membership...................................................$45/yr. Subscription (only)........................................$30/yr. ‘Threshold’, Public Art by Brian Goldbloom ... 10 Please Note: Only full memberships at $45/yr. include voting privileges and discounted member rates at symposia and workshops. MISSION STATEMENT The purpose of the NWSSA’s Sculpture NorthWest Journal is to promote, educate, and inform about stone sculpture, and to share experiences in the appreciation and execution of stone sculpture. -

Madison Community Foundation 2020 Annual Report

Annual Report 2020 On the Cover The Downtown Street Art and Mural Project As the nation struggled to contain the coronavirus pandemic, it was further rocked by the death of George Floyd on May 25 while in the custody of the Minneapolis police. Floyd’s death set off protests across the nation, and around the world. In Madison, peaceful daytime protests were followed by looting in the evenings, which forced many businesses to shutter their storefronts with plywood. The Madison Arts Commission, funded in part by a Community Impact grant from Madison Community Foundation (MCF), responded to the bleak sight of State Street by creating the Downtown Street Art and Mural Project, which engaged dozens of local artists to use these spaces as an opportunity for expression and civic engagement. More than 100 murals, including the one on our cover, were painted in and around State Street, creating a vibrant visual dialogue addressing racism, memorializing lost lives and inspiring love. Artists participated in panel discussions and were highlighted in local and national media. “Let’s Talk About It: The Art, The Artists and the Racial Justice Movement on Madison’s State Street,” a book focused on the project, was produced by (and is available through) the American Family Insurance Institute for Corporate and Social Impact. In addition, several of the murals will become part of the permanent collection of the Wisconsin Historical Museum. MCF’s long-standing vision — that greater Madison will be a vibrant and generous place where all people thrive — is impossible to achieve without ending racism. We remain committed to this journey. -

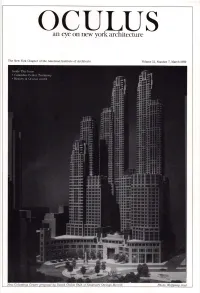

An Eye on New York Architecture

OCULUS an eye on new york architecture The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 ew Co lumbus Center proposal by David Childs FAIA of Skidmore Owings Merrill. 2 YC/AIA OC LUS OCULUS COMING CHAPTER EVENTS Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 Oculus Tuesday, March 7. The Associates Tuesday, March 21 is Architects Lobby Acting Editor: Marian Page Committee is sponsoring a discussion on Day in Albany. The Chapter is providing Art Director: Abigail Sturges Typesetting: Steintype, Inc. Gordan Matta-Clark Trained as an bus service, which will leave the Urban Printer: The Nugent Organization architect, son of the surrealist Matta, Center at 7 am. To reserve a seat: Photographer: Stan Ri es Matta-Clark was at the center of the 838-9670. avant-garde at the end of the '60s and The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects into the '70s. Art Historian Robert Tuesday, March 28. The Chapter is 457 Madison Avenue Pincus-Witten will be moderator of the co-sponsoring with the Italian Marble New York , New York 10022 evening. 6 pm. The Urban Center. Center a seminar on "Stone for Building 212-838-9670 838-9670. Exteriors: Designing, Specifying and Executive Committee 1988-89 Installing." 5:30-7:30 pm. The Urban Martin D. Raab FAIA, President Tuesday, March 14. The Art and Center. 838-9670. Denis G. Kuhn AIA, First Vice President Architecture and the Architects in David Castro-Blanco FAIA, Vice President Education Committees are co Tuesday, March 28. The Professional Douglas Korves AIA, Vice President Stephen P. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

November 29, 2020 Washington National Cathedral

WELCOME washington national cathedral November 29, 2020 An Online House of Prayer for All People Preaching Today Even though our building is closed temporarily, we’re The Rev. Adam Hamilton, senior committed to bringing all the warmth, beauty and God’s pastor United Methodist Church of the presence in the Cathedral directly to you! We invite you to Resurrection, Leawood, Kans. interact with us in new ways, and we hope you find a measure of comfort and God’s grace in these challenging times. Presiding Today COVID-19 closures have disrupted life for everyone, and The Right Rev. Mariann Edgar Budde we know this is a difficult time for many. You can help the Cathedral provide comfort and hope for our nation. Give today at cathedral.org/support Your Online Cathedral COVID Memorial Prayers Enjoy exclusive online content at cathedral.org. Saturdays, 7 am As COVID-19 cases begin to rise again, prayer requests we invite you to submit the of loved ones lost to the coronavirus to be recognized in a Submit prayers for yourself, those you love or the world. During the names week we offer these prayers during a time of prayer and intercession. weekly memorial service. prayers for covid-19 deaths Sunday Evenings in Advent Each week we prayer for those lost to the COVID-19 pandemic. Submit Sundays, November 29–December 20, 6 pm the names of those lost to be included in the service. “Prepare Ye the Way of the Lord”—Make room in your heart for the coming season of joy with a series contemplative and inspirational Next Sunday services of prayer and music shaped by the words of the prophet preaching at 11:15 am Isaiah. -

Who's Who at the Rodin Museum

WHO’S WHO AT THE RODIN MUSEUM Within the Rodin Museum is a large collection of bronzes and plaster studies representing an array of tremendously engaging people ranging from leading literary and political figures to the unknown French handyman whose misshapen proboscis was immortalized by the sculptor. Here is a glimpse at some of the most famous residents of the Museum… ROSE BEURET At the age of 24 Rodin met Rose Beuret, a seamstress who would become his life-long companion and the mother of his son. She was Rodin’s lover, housekeeper and studio helper, modeling for many of his works. Mignon, a particularly vivacious portrait, represents Rose at the age of 25 or 26; Mask of Mme Rodin depicts her at 40. Rose was not the only lover in Rodin's life. Some have speculated the raging expression on the face of the winged female warrior in The Call to Arms was based on Rose during a moment of jealous rage. Rose would not leave Rodin, despite his many relationships with other women. When they finally married, Rodin, 76, and Rose, 72, were both very ill. She died two weeks later of pneumonia, and Rodin passed away ten months later. The two Mignon, Auguste Rodin, 1867-68. Bronze, 15 ½ x 12 x 9 ½ “. were buried in a tomb dominated by what is probably the best The Rodin Museum, Philadelphia. known of all Rodin creations, The Thinker. The entrance to Gift of Jules E. Mastbaum. the Rodin Museum is based on their tomb. CAMILLE CLAUDEL The relationship between Rodin and sculptor Camille Claudel has been fodder for speculation and drama since the turn of the twentieth century. -

Outdoor Sculpture Walk

Outdoor Sculpture Walk Walla Walla, Washington 5 To begin your outdoor sculpture Back toward Ankeny Field and Maxey Hall, you tour, park in the Hall of Science will see a dark brown metal sculpture. parking lot and proceed east past the Rempel Greenhouse to Ankeny 5. Lava Ridge, 1978, Lee Kelly. A noted artist Field for the tour’s first piece. from Oregon City, Ore., Kelly draws inspiration from ancient and contemporary sources. This steel 1. Styx, 2002, Deborah sculpture was acquired in 2002 with funds from the Garvin Family Art Fund. Butterfield. An artist from Bozeman, Mont., Butterfield acquired the original driftwood for the horse from the Columbia and Snake rivers. The bronze was cast at the Walla Walla 1 Foundry, owned and operated by Whitman 6 Follow the sidewalk on the east end of alumnus Mark Anderson ’78. Maxey Hall, and you will see two totem poles. Head straight up the left side of Ankeny Field to the northeast corner and Jewett Hall’s terrace. There you will see two 6. The Benedict Totem was donated by students in deep concentration. Lloyd Benedict ’41. 2. Students Playing 4D Tic Tac Toe, 1994, Richard Beyer. Throughout the Northwest, Beyer is known for his realistic public art. This 7 7. Totem Pole, 2000, Jewell Praying Wolf piece, cast in aluminum, was commissioned by James. A master carver of the Lummi Nation of the Class of 1954 and represents both the Native Americans of northwestern Washington, 2 intellectual and playful aspects of college life. James carved the 24-foot totem from western red cedar in a combination of Coast Salish and Alaska 3 Native styles. -

35800 PKZ KA-8 BNF PNP Manual .Indb

Ka-8 Instruction Manual / Bedienungsanleitung Manuel d’utilisation / Manuale di Istruzioni EN NOTICE All instructions, warranties and other collateral documents are subject to change at the sole discretion of Horizon Hobby, Inc. For up-to-date product literature, visit www.horizonhobby.com and click on the support tab for this product. Meaning of Special Language: The following terms are used throughout the product literature to indicate various levels of potential harm when operating this product: NOTICE: Procedures, which if not properly followed, create a possibility of physical property damage AND little or no possibility of injury. CAUTION: Procedures, which if not properly followed, create the probability of physical property damage AND a possibility of serious injury. WARNING: Procedures, which if not properly followed, create the probability of property damage, collateral damage, and serious injury OR create a high probability of superfi cial injury. WARNING: Read the ENTIRE instruction manual to become familiar with the features of the product before operating. Failure to operate the product correctly can result in damage to the product, personal property and cause serious injury. This is a sophisticated hobby product. It must be operated with caution and common sense and requires some basic mechanical ability. Failure to oper- ate this Product in a safe and responsible manner could result in injury or damage to the product or other property. This product is not intended for use by children without direct adult supervision. Do not use with incompatible components or alter this product in any way outside of the instructions provided by Horizon Hobby, Inc. This manual contains instructions for safety, operation and maintenance. -

Heaven and Hell.Pmd

50 Copyright © 2002 The Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University This photo is available in the print version of Heaven and Hell. Though Auguste Rodin struggled over twenty years to express through sculpture the desperation of souls that are falling from Grace, he never finished his magnificent obsession. Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), THE GATES OF HELL, 1880-1900, Bronze, 250-3/4 x 158 x 33-3/8 in. Posthumous cast authorized by Musée Rodin, 1981. Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University; gift of the B. Gerald Cantor Collection. Photograph by Frank Wing. The Final Judgment in Christian Art 51 Falling BY HEIDI J. HORNIK uguste Rodin accepted his first major commission, The Gates of Hell, when he was forty years old. This sculpture was to be the door- Away for the École des Arts Dècoratifs in Paris. Though the muse- um of decorative arts was not built, Rodin struggled over twenty years to depict the damned as they approach the entrance into hell. He never finished. The sculpture was cast in bronze after the artist’s death, using plaster casts taken from his clay models. The Gates of Hell, like Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, lays out its mean- ing through a turbulent and multi-figured design. The identities of many figures in the composition are not immediately apparent. Instead Rodin challenges us to make sense of the whole work by dissecting its elements and recalling its artistic influences.† The Three Shades at the very top, for example, derives from Greek thought about Hades. -

Originality Statement

PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Hosseinabadi First name: Sanaz Other name/s: Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: School of Architecture Faculty: Built Environment Title: Residual Meaning in Architectural Geometry: Tracing Spiritual and Religious Origins in Contemporary European Architectural Geometry Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Architects design for more than the instrumental use of a buildings. Geometry is fundamental in architectural design and geometries carry embodied meanings as demonstrated through the long history of discursive uses of geometry in design. The meanings embedded in some geometric shapes are spiritual but this dimension of architectural form is largely neglected in architectural theory. This thesis argues that firstly, these spiritual meanings, although seldom recognised, are important to architectural theory because they add a meaningful dimension to practice and production in the field; they generate inspiration, awareness, and creativity in design. Secondly it will also show that today’s architects subconsciously use inherited geometric patterns without understanding their spiritual origins. The hypothesis was tested in two ways: 1) A scholarly analysis was made of a number of case studies of buildings drawn from different eras and regions. The sampled buildings were selected on the basis of the significance of their geometrical composition, representational symbolism of embedded meaning, and historical importance. The analysis clearly traces the transformation, adaptation or representation of a particular geometrical form, or the meaning attached to it, from its historical precedents to today. 2) A scholarly analysis was also made of a selection of written theoretical works that describe the design process of selected architects.