Tools and Machinery of the Granite Industry Donald D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Thesis Text Only

A DIACHRONIC EXAMINATION OF THE ERECHTHEION AND ITS RECEPTION Alexandra L. Lesk, B.A., M.St. (Oxon.), M.A. Presented to McMicken College of Arts and Sciences and the Department of Classics of the University of Cincinnati in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2004 Committee: C. Brian Rose (Chair) Jack L. Davis Kathleen M. Lynch J. James Coulton Abstract iii ABSTRACT “A Diachronic Examination of the Erechtheion and Its Reception” examines the social life of the Ionic temple on the Athenian Akropolis, which was built in the late 5th century B.C. to house Athens’ most sacred cults and relics. Using a contextualized diachronic approach, this study examines both the changes to the Erechtheion between its construction and the middle of the 19th century A.D., as well as the impact the temple had on the architecture and art of these successive periods. This approach allows the evidence to shed light on new areas of interest such as the Post-Antique phases of the building, in addition to affording a better understanding of problems that have plagued the study of the Erechtheion during the past two centuries. This study begins with a re-examination of all the pertinent archaeological, epigraphical, and literary evidence, and proposes a wholly new reconstruction of how the Erechtheion worked physically and ritually in ancient times. After accounting for the immediate influence of the Erechtheion on subsequent buildings of the Ionic order, an argument for a Hellenistic rather than Augustan date for the major repairs to the temple is presented. -

Building a Battle Station Model by Russell Barnes

Building a Battle Station Model By Russell Barnes I. Introduction The summer is usually a pretty difficult time for me to work in my workshop. Chores abound around the house and there is seemingly some-thing to do almost every day that precludes any useful time spent in the workshop. The summer of 2004 was no different. By the time late July rolled around, I was desperate. I had not made anything for over a month. Something had to be done. What to do? Then it hit me. I was looking over the latest Model Expo catalogue and saw they still offered kit models of small battle stations. Not wanting to build a kit, I saw the potential for a quick scratch built project. Over the next two weeks I built a battle station model that turned out to be quite a conversation piece. As fate would have it, that model was destroyed when Hurricane Katrina washed away the local museum. I have decided to replace the battle station model, but it occurred to me that others might benefit from my experience having built it. So, I redrew the plans, making some improve-ments, and decided to set down a guide to building the model. I am not an expert and I make no claim that my methods are the only way to build the model. Someone building from these plans should view my words as a collection of helpful hints rather than a map to follow in order to arrive at a desired result. I envision this project as an introduction to scratch building. -

Chelmsford-1958.Pdf (14.23Mb)

Jown of Chelmdtord ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDING DECEMBER 31, 1958 Itt Hfomonam FIRE CHIEF ALLAN KIDDER Allan Kidder, Chief of the Fire Department, died on November 4, 1958. Chief Kidder was first appointed a call firefighter in 1931. After serving his country in World War II, he returned to the Fire Department in 1946 as a regular firefighter. He rose rapidly in rank until in 1954 he was appointed as Chelmsford's first full- time Fire Chief. His untimely passing put an end to a career dedicated to the Fire Service, a career in which he earned the respect of his fellow-workers and of the Townspeople. SULLIVAN BROS. LOWELL, MASS. ANNUAL REPORT OF THE ^Jown of CkeLsfoJ FOR THE YEAR ENDING DECEMBER 31, 1958 ANNUAL TOWN REPORT Report of the Town Clerk ELECTED TOWN OFFICIALS MODERATOR Edward J. Desaulnier, Jr. (Term Expires 1960) Resigned Jan. 13, 1959 TOWN CLERK Charlotte P. DeWolf (Term Expires 1960) SELECTMEN AND BOARD OF PUBLIC WELFARE Edgar P. George Term Expires 1959 Robert F. McAndrew Term Expires 1960 Raymond J. Greenwood Term Expires 1961 TREASURER AND TAX COLLECTOR Charlotte P. DeWolf, Temporary until Feb. 1959 Walter R. Wilkins, Jr. Term Expires 1960 BOARD OF ASSESSORS Warren Wright Term Expires 1959 John J. Dunigan - Term Expires 1960 Claude A. Harvey _ Term Expires 1961 TREE WARDEN Myles J. Hogan (Term Expires 1960) BOARD OF HEALTH William R. Greenwood _ Term Expires 1959 Edmund J. Welch Term Expires 1960 Oliver A. Reeves Term Expires 1961 8 ANNUAL TOWN REPORT SCHOOL COMMITTEE Allan R. Davidson Term Expires 1959 Henrick R. -

Steel an Irreversible Decline ?

10 June 1981 Marxism Today John Kelly Steel an irreversible decline ? In its Ten Year Development Strategy published in 1973, the British the new Tory government in 1951, and the industry was then Steel Corporation estimated that in 1980 it would produce 36-38 denationalised in 1953.3 million tonnes of steel per annum. It actually produced just 11.4 From 1940 onwards the structural weaknesses of the industry — in million tonnes, only one third of its plan target. In those seven particular the dispersion of production amongst a large number of intervening years the industry has been run down at an almost small, old and independently owned plants — were masked by a unprecedented rate. Steel plants throughout the country have been sustained period of buoyant demand during the war, the period of closed; over 100,000 steel workers have lost their jobs; steel towns like reconstruction, and the postwar boom. Nevertheless the rate of profit Shotton and Corby have been devastated; and import penetration in did decline, from 15% (1956), 14.2% (1960) to 6.1% in 1964, and one steel has nearly doubled.1 To this bleak picture must be added the response by the steel capitalists was a long overdue increase in capital decline of several other major British steel-using industries. Imports investment from £93m in 1956 to a peak of £207m in 1961, with a fall of cars, refrigerators, washing machines, radios, cutlery and hand off to £77m in 1963. This increased investment in the late 1950s failed tools have grown dramatically in the 1970s. -

Dave's Decision: Whether to Weather

Volume 37, No. 5 June, 2008 PUBLISHED BY THE LIONEL® COLLECTORS CLUB OF AMERICA IN FEBRUARY, APRIL, JUNE, OCTOBER, DECEMBER Dave’s Decision: Whether to Weather The Lion Roars June, 2008 LAST CHANCE TO ORDER Deadline Imminent The Lionel Collectors Club of America offers these two This limited-edition production run will include these quality distinctive cars of the northeast region — “Susie Q” and Ontario features: Northland RR — to members as the 2008 Convention car. Limit: • produced by Lionel® exclusively for LCCA two sets per member. • die-cast, fully sprung trucks with rotating roller bearing caps; truck sideframes are painted to match the cars The Susquehanna car will include the classic rendering of the • roof hatches actually open and close “Susie Q” character never before presented on a hopper car. This • crisp graphics with SUSIE Q and ONR décor pair will appeal to Susie Q and Canadian model railroaders, niche • added-on (not molded-in) ladders and brake wheels collectors seeking rolling stock of northeastern regional railroads, • detailed undercarriage and collectors of LCCA Convention cars. • discrete LCCA 2008 Convention designation on the underside. Order Form for “Susie Q” and ONR Cars Once submitted, LCCA will consider this a firm, non-refundable order. Deadline for ordering: June 30, 2008. Note: UPS cannot deliver to a post office box. A street address is required. Name: ____________________________________________________________________ LCCA No.: ________________ Address: ____________________________________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________________________________________________ State: ____ Zip + 4: __________________ Phone: (______) ______________________ e-mail: __________________________________________________________ [ ] Check this box if any part of your address is new. Do the Math: [ ] Payment Plan A: My check for the full amount is enclosed made payable to 2008 LCCA Convention Car “LCCA” with “TLR/2008CC” written on the memo line. -

ATTORNEYS March 6, 1951 T

Mareh 6, 1951 T. o. DAVIDSON ETAL 2,543,765 wmcn FOR convsmmua DRAGLINES AND SHOVELS Filed Feb. 5, 1947 6 Sheets-Sheet 1 BY 4' ATTORNEYS March 6, 1951 T. o. DAVIDSON ETAL 2,543,765 wmcu FOR CONVERTIBLE DRAGLINES AND SHOVELS Filed Feb. 5, 1947 6 Sheets-Sheet 2 .59 4/40 .75 ' ATTORAGE‘Yi March 6, 1951 T. o. DAVIDSON ET AL 2,543,755 WINCH FOR CQNVERTIBLE DRAGLINES AND SHOVELS Filed Feb. 5, 1947 6 Sheets-Sheet 3 76 ‘32 74 74 49 7 £3 47 62 II:- I: W 7a’ 3 74 74 1 686.5’ 69 50 v’ 48 J2 49 a a 5/ H , l ' éz‘; I 59,-. ism"? 7’ ATTORNEY-5' March 6, 1951 'r. o. DAVIDSON ETAL 2,543,765 WINCH FOR CONVERTIBLE DRAGLINES AND SHOVELS Filed Feb. 5, 1947 6 Sheets-Sheet 4 ATTORNEY.’ March 6, 1951 ‘r. o. DAVIDSON ETAL 2,543,755 wmcu FOR convaansus DRAGLINES AND SHOVELS Filed Feb. 5, 1947 6 Sheets-Sheet 5 M “amid/4m. mmvroas, 2% 2,5 ‘ ATTORNEY. March 6, 1951 -r. o. DAVIDSON ETAL 2,543,765 wmcn FOR convamxau-z nmcu‘m-zs AND SHOVELS AZTORJVEYI Patented Mar. 6, 1951 2,543,765 UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE 2,543,765 WINCH FOR CONVERTIBLE DRAGLINES AND SHOVELS Trevor 0. Davidson, Milwaukee, and Bruno L. Lonngren, South Milwaukee, Wis., assignors to Bucyrus-Erie Company, South Milwaukee, Wis., a corporation of Delaware . Application February 5, 1947, Serial No. 726,570 19 Claims. (CL 254—185) 1 Our invention relates to new and useful im Rope thrusting eliminates the need of a boom provements in the control of thrusting and hoist engine to drive the shipper shaft, and thus not ing functions of power shovels, and the control only thereby reduces the weight on the boom, ' of dragging and hoisting functions of draglines but also reduces the weight of the boom itself by more particularly power shovels and draglines of enabling it to be built lighter. -

Guide to Concrete Repair Second Edition

ON r in the West August 2015 Guide to Concrete Repair Second Edition Prepared by: Kurt F. von Fay, Civil Engineer Concrete, Geotechnical, and Structural Laboratory U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Technical Service Center August 2015 Mission Statements The U.S. Department of the Interior protects America’s natural resources and heritage, honors our cultures and tribal communities, and supplies the energy to power our future. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Acknowledgments Acknowledgment is due the original author of this guide, W. Glenn Smoak, for all his efforts to prepare the first edition. For this edition, many people were involved in conducting research and field work, which provided valuable information for this update, and their contributions and hard work are greatly appreciated. They include Kurt D. Mitchell, Richard Pepin, Gregg Day, Jim Bowen, Dr. Alexander Vaysburd, Dr. Benoit Bissonnette, Maxim Morency, Brandon Poos, Westin Joy, David (Warren) Starbuck, Dr. Matthew Klein, and John (Bret) Robertson. Dr. William F. Kepler obtained much of the funding to prepare this updated guide. Nancy Arthur worked extensively on reviewing and editing the guide specifications sections and was a great help making sure they said what I meant to say. Teri Manross deserves recognition for the numerous hours she put into reviewing, editing and formatting this Guide. The assistance of these and numerous others is gratefully acknowledged. Contents PART I: RECLAMATION'S METHODOLOGY FOR CONCRETE MAINTENANCE AND REPAIR Page A. -

Depave Guide Replacing Impervious Parking Lot with Green Spaces

a little less grey a little more green The Depave Guide replacing impervious parking lot with green spaces Depave a program of Cuyahoga River Restoration Content adapted from, and in partnership with, Depave of Portland, OR • depave.org Based on “How to Depave: A Guide to Freeing Your Soil” by Depave Adapted with permission, and with grateful acknowledgment to the Depave team in Portland, OR © 2017 Cuyahoga River Community Planning 1299 Superior Ave E, Cleveland, OH 44114 Made possible with a grant from the Ohio Environmental Education Fund Ohio Environmental Protection Agency GETTING FROM GREY TO GREEN WE’VE GOT WAY TOO MUCH PAVED IMPERVIOUS SURFACE. IT’S MAKING OUR CITIES FLOOD AND OUR STREAMS UNHEALTHY. Impervious surface that covers our roads, parking lots, driveways, and roofs is the most widespread obstacle to protecting water quality in rivers and streams. It causes flooding and has significant negative effects on the environment. Parking lots are a major problem, not just in urban areas but everywhere. Aside from increasing runoff volume, parking lots contribute nutrient and chemical contaminants from road salt, degraded asphalt, worn tire treads, automotive fluids, fertilizers, and herbicides. They also increase the heat island effect, making buildings nearby, and automobiles parking there, use more energy to cool down. As a typical example, 31% of the land in Cuyahoga County in Northeast Ohio is covered in impervious surface. Parking lots represent 14% of that total. The Center for Watershed Protection sets 25% impervious as the level above which serious damage is done to water quality. If we could convert half of that 14% to absorptive greenspace, we could reach the point where we can protect rather than degrade our water, air, and human health. -

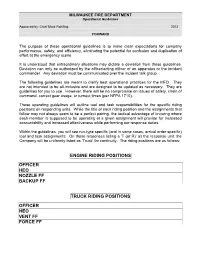

Engine Riding Positions Officer Heo Nozzle Ff

MILWAUKEE FIRE DEPARTMENT Operational Guidelines Approved by: Chief Mark Rohlfing 2012 FORWARD The purpose of these operational guidelines is to make clear expectations for company performance, safety, and efficiency, eliminating the potential for confusion and duplication of effort at the emergency scene. It is understood that extraordinary situations may dictate a deviation from these guidelines. Deviation can only be authorized by the officer/acting officer of an apparatus or the incident commander. Any deviation must be communicated over the incident talk group. The following guidelines are meant to clarify best operational practices for the MFD. They are not intended to be all-inclusive and are designed to be updated as necessary. They are guidelines for you to use. However, there will be no compromise on issues of safety, chain of command, correct gear usage, or turnout times (per NFPA 1710). These operating guidelines will outline tool and task responsibilities for the specific riding positions on responding units. While the title of each riding position and the assignments that follow may not always seem to be a perfect pairing, the tactical advantage of knowing where each member is supposed to be operating at a given assignment will provide for increased accountability and increased effectiveness while performing our response duties. Within the guidelines, you will see run-type specific (and in some cases, arrival order specific) tool and task assignments. On those responses listing a ‘T (or R)’ as the response unit, the Company will be uniformly listed as ‘Truck’ for continuity. The riding positions are as follows: ENGINE RIDING POSITIONS OFFICER HEO NOZZLE FF BACKUP FF TRUCK RIDING POSITIONS OFFICER HEO VENT FF FORCE FF SAFETY If you see something that you believe impacts our safety, it is your duty to report it to your superior Officer immediately. -

The Art of Stone Masonry in the Rockbridge County Area (1700 to Present)

The Art of Stone Masonry In the Rockbridge County Area (1700 to present) Steven Connett Archaeology 377 5/25/83 Dr. McDaniel The art of stone masonry in the Shenandoah valley seems to be somewhat of a mystery prior to the nineteenth century. However, as some of us have learned from the anthropology 101 course: The absence of artifacts (documents in this case) is just as important as the presence of artifacts. In order to make sure that the lack of information was not due to my possible incompetence in research, I spoke with a current day stone masoner named Alvis Reynolds. Mr. Reynolds relayed t o me that when he was trying to learn the skills of stone masonry he, too, had great difficulty in obtaining information and thus decided to teach himself this art through the process of trial and error. Although this information did not directly aid me in my research, Mr. Reynolds did provide me with a bit of information that allowed me to derive a hypothesis on why there is this unusual lack of information in this line of study. I will state my hypothesis in this paper, however, I will not be able to prove it or disprove it due to the deficiency in available information. Mr. Reynolds explained to me that in the eighteenth century there were nomadic stone masoners. These nomadic workers went from valley to valley in search of people who needed help with building their houses. Since these people did not know how to cut stone themselves (after all, stone cutting is not the type of thing that is innate to most people) they had no choice but to p~y these men for their services or go unsheltered. -

2014 Rules & Regs

! ! ! RULES AND REGULATIONS ! ! Revised and Adopted by Ivy Lawn Board of Directors __________________________! Revised 01/01/2014! ! ! IVY LAWN MEMORIAL PARK! & FUNERAL HOME A California Non Profit Public! Benefit Corporation 5400 Valentine Road • Ventura, CA 93003! • Tel. (805) 642-1055 • ivylawn.org ! ! ! ! !1 ! ! ! ! TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT IVY LAWN 4 PREAMBLE 5 MAINTENANCE STANDARDS PRIVACY POLICY 1.01 HUMAN BURIAL SUBJECT TO LAWS 8 1.02 AUTHORIZATIONS 8 1.03 CASKET 9 1.04 CONDUCT OF FUNERALS AND SERVICES 9 1.05 CONTAINERS FOR CREMATED REMAINS 9 1.06 OUTER BURIAL CONTAINER 1.07 LOCATION OF GRAVES 9 1.08 SCATTERING GARDEN 1.09 INTERMENT OF UNCLAIMED CREMATED REMAINS 10 1.10 CREMATION PROCEDURES 10 1.11 WITNESSED CREMATIONS 11 1.12 DATE RESTRICTIONS 12 1.13 DELAYS 12 1.14 CHARGES FOR SERVICES 13 1.15 IVY LAWN’S EQUIPMENT MUST BE USED 13 1.16 ERRORS MAY BE CORRECTED 13 1.17 CARE IN REMOVAL 13 1.18 DISINTERMENT OF MULTIPLE GRAVES 13 2. RIGHTS OF PROPERTY OWNERS 13 2.01 STATUTORY BASIS 13 2.02 BURIAL RIGHTS OF PROPERTY OWNERS 14 2.03 MULTIPLE BURIALS IN ONE PROPERTY 15 2.04 FAMILY PLOTS 2.05 DESCENT OF PROPERTY RIGHTS 17 2.06 SUBDIVISION OF PROPERTY 17 2.07 TRANSFERS AND ASSIGNMENTS 17 2.08 CHANGE IN ADDRESS OF PROPERTY OWNERS 17 2.09 WRITTEN AGREEMENT 17 2.10 NO RIGHT GRANTED IN ROADWAYS 18 2.10 DEVELOPMENT OF PROPERTY BY OWNER 18 3. GENERAL SUPERVISION OF CEMETERY 18 3.01 ADMISSION TO CEMETERY 18 3.02 CONDUCT WITHIN THE CEMETERY 18 3.03 CHAPEL 19 3.04 DECORATIONS 19 !2 3.05 FEES, GRATUITIES AND COMMISSIONS 20 3.06 USE OF SECURITY SERVICE 20 3.07 WORK TO BE DONE BY IVY LAWN 20 3.08 IMPROVEMENTS 20 3.09 ROADWAYS AND REPLATTING 20 3.10 NON-RESPONSIBILITY FOR DAMAGES AND NOTICE FOR REPAIR 20 4. -

Mar 20100022: Crowsnest North

MAR 20100022: CROWSNEST NORTH Received date: Dec 02, 2010 Public release date: Dec 06, 2011 DISCLAIMER By accessing and using the Alberta Energy website to download or otherwise obtain a scanned mineral assessment report, you (“User”) agree to be bound by the following terms and conditions: a) Each scanned mineral assessment report that is downloaded or otherwise obtained from Alberta Energy is provided “AS IS”, with no warranties or representations of any kind whatsoever from Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Alberta, as represented by the Minister of Energy (“Minister”), expressed or implied, including, but not limited to, no warranties or other representations from the Minister, regarding the content, accuracy, reliability, use or results from the use of or the integrity, completeness, quality or legibility of each such scanned mineral assessment report; b) To the fullest extent permitted by applicable laws, the Minister hereby expressly disclaims, and is released from, liability and responsibility for all warranties and conditions, expressed or implied, in relation to each scanned mineral assessment report shown or displayed on the Alberta Energy website including but not limited to warranties as to the satisfactory quality of or the fitness of the scanned mineral assessment report for a particular purpose and warranties as to the non-infringement or other non-violation of the proprietary rights held by any third party in respect of the scanned mineral assessment report; c) To the fullest extent permitted by applicable law, the Minister,