The Flâneuse's Old Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Eye on New York Architecture

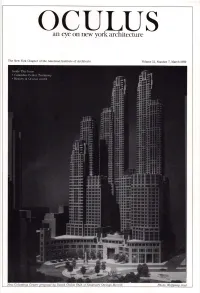

OCULUS an eye on new york architecture The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 ew Co lumbus Center proposal by David Childs FAIA of Skidmore Owings Merrill. 2 YC/AIA OC LUS OCULUS COMING CHAPTER EVENTS Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 Oculus Tuesday, March 7. The Associates Tuesday, March 21 is Architects Lobby Acting Editor: Marian Page Committee is sponsoring a discussion on Day in Albany. The Chapter is providing Art Director: Abigail Sturges Typesetting: Steintype, Inc. Gordan Matta-Clark Trained as an bus service, which will leave the Urban Printer: The Nugent Organization architect, son of the surrealist Matta, Center at 7 am. To reserve a seat: Photographer: Stan Ri es Matta-Clark was at the center of the 838-9670. avant-garde at the end of the '60s and The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects into the '70s. Art Historian Robert Tuesday, March 28. The Chapter is 457 Madison Avenue Pincus-Witten will be moderator of the co-sponsoring with the Italian Marble New York , New York 10022 evening. 6 pm. The Urban Center. Center a seminar on "Stone for Building 212-838-9670 838-9670. Exteriors: Designing, Specifying and Executive Committee 1988-89 Installing." 5:30-7:30 pm. The Urban Martin D. Raab FAIA, President Tuesday, March 14. The Art and Center. 838-9670. Denis G. Kuhn AIA, First Vice President Architecture and the Architects in David Castro-Blanco FAIA, Vice President Education Committees are co Tuesday, March 28. The Professional Douglas Korves AIA, Vice President Stephen P. -

BRYANT PARK in Celebration of Gabriel Kreuther's Second

christian boone BRYANT PARK In celebration of Gabriel Kreuther’s second anniversary and the 25th anniversary of Bryant Park as we know it today, we are delighted to present to you a cocktail menu that will allow you to travel through the history of our community and discover the secrets of the park and the New York public. Potter’s Field Illegal Mezcal • Lillet Blanc • St-Germain • Black Cardamom • Lemon ~ One of the first known uses for Bryant Park was as a potter’s field in 1823; its purpose was a graveyard for society’s solitary and indigent. It remained so until 1840, when the city decommissioned it and thousands of bodies were moved to Wards Island in prepara- tion for the construction of the Croton Reservoir. The Reservoir Ketel One Vodka • Red Pepper • Oregano • Lemon • Absinthe ~ The Croton Distributing Reservoir was surrounded by 50-foot high, thick granite walls and supplied the city with drinking water during the 19th century. Along the tops of the walls were public promenades where Edgar Allan Poe enjoyed his walks. A remnant of the reservoir can still be seen today in the New York Public Library. Washington’s Troop Michter’s Rye • Massenez Crème de Pêche • Apricot • Lemon • Rosemary ~ General George Washington solemnly crossed the park with his troops after suffering a defeat at the battle of Brooklyn in 1776, the first major battle of the war to take place after America declared independence on July 4th, 1776. After the battle, the British held CHAPTER I New York City for the remainder of the Revolutionary War. -

A Structural Analysis of Constantin Brancusi's

A STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS OF CONSTANTIN BRANCUSI'S STONE SCULPTURE by LESLIE ALLAN DAWN B.A., M.A., University of Victoria A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Art History We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard © LESLIE ALLAN DAWN UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 1982 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part3 by mimeograph or other means3 without the permission of the author. In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Ws>TQg.»? CF E)g.T The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date (3/81) i i ABSTRACT It has long been recognized by Sidney Geist and others that Constantin Brancusi's stone work, after 1907, forms a coherent totality in which each component depends on its relationship to the whole for its significance; in short, the oeuvre comprises a rigorous sculptural language. Up to the present, however, formalist approaches have proven insufficient for decodifying the clear design which can be intuited in the language. -

Polishing the Jewel

Polishing the Jewel An Administra ti ve History of Grand Canyon Na tional Pa rk by Michael F.Anderson GRA N D CA N YO N A S S OC I ATI O N Grand Canyon Association P.O. Box 399 Grand Canyon, AZ 86023 www.grandcanyon.org Grand Canyon Association is a non-profit organization. All proceeds from the sale of this book will be used to support the educational goals of Grand Canyon National Park. Copyright © 2000 by Grand Canyon Association. All rights reserved. Monograph Number 11 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Anderson, Michael F. Polishing the jewel : an adminstrative history of Grand Canyon National Park/by Michael F.Anderson p. cm. -- (Monograph / Grand Canyon Association ; no. 11) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-938216-72-4 1. Grand Canyon National Park (Ariz.)--Management—History. 2.Grand Canyon National Park (Ariz.)--History. 3. United States. National Park Service—History. I. Title. II. Monograph (Grand Canyon Association) ; no. 11. F788 .A524 2000 333.78’3’0979132--dc21 00-009110 Edited by L. Greer Price and Faith Marcovecchio Designed by Kim Buchheit, Dena Dierker and Ron Short Cover designed by Ron Short Printed in the United States of America on recycled paper. Front cover: Tour cars bumper-to-bumper from the Fred Harvey Garage to the El Tovar Hotel, ca.1923. Traffic congestion has steadily worsened at Grand Canyon Village since the automobile became park visitors’ vehicle of choice in the mid-1920s.GRCA 3552; Fred Harvey Company photo. Inset front cover photo: Ranger Perry Brown collects a one dollar “automobile permit” fee at the South Rim,1931.GRCA 30. -

Cool Running NEW YORK — What Do You Get When You Cross Bob Marley with Babe Paley? “Babe Marley,” According to Michael Kors

ART COOPER, RENOWNED GQ EDITOR, DEAD AT 65/3 Women’sWWD Wear Daily • The Retailers’TUESDAY Daily Newspaper • June 10, 2003 Vol. 185, No. 117 $2.00 Ready-to-Wear/Textiles Cool Running NEW YORK — What do you get when you cross Bob Marley with Babe Paley? “Babe Marley,” according to Michael Kors. For resort, the designer opted for the ultimate in chic island-hopping looks, splicing the laid-back Jamaican style of the iconic rocker with the ladylike cool of the jet- setter. Here, his tie-dyed rayon jersey and elastin top and suede miniskirt. For more, see pages 6 and 7. Prada’s Latest Glow: Luxury Group Unveils $83M Tokyo Landmark By Tsukasa Furukawa TOKYO — Prada has another eye- catching Epicenter. The luxury group last week opened a six-story, 28,000-square- foot flagship here that has a facade covered in hundreds of glass panels in a diamond-shaped grid. The store is located in Tokyo’s fashionable Aoyama shopping district and offers a new landmark in this sprawling city. Prada terms the building another one of its “Epicenter” stores, the first of which opened in SoHo in See Prada, Page21 PHOTO BY PHOTO THOMAS BY IANNACCONE 2 PPR, Artemis Deny Rumors WWDTUESDAY Ready-to-Wear/Textiles Over Exec Changes at Gucci FASHION Rule number one for the girl on the go is to travel in style, whether jetting off By Amanda Kaiser Gucci, is not contacting candi- “We both have an incredible 6 to a tropical locale or zipping out to the coast for a weekend. -

A Temporary Androgyne for Lynda Benglis and Richard Tuttle)

_____________ In the Meantime, Examples of the Same Lily (A temporary androgyne for Lynda Benglis and Richard Tuttle) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Royal College of Art for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lee Triming December 2015 _____________ pink out of a corner (to Jasper Johns) In Buddhist mythology, the god Indra owned a net of jewels, each of which reflected each one of its fellows to infinity. A structure wherein each element, in relation to every other, leads endlessly away from itself. In The Infinite Conversation, Blanchot frames speech as detour.1 In the work of writers as diverse as Gertrude Stein and Henry James, various deployments of language turn the reader away, on numerous levels, from plot and character, from nouns and facts, from linear progression, from coherent narrative, clarity and cognition, engaging with reading as movement and encounter rather than as a progressive accumulation of quanta in the service of constructing a singular truth.2 Robert Rauschenburg once sent a telegram to Iris Clert saying “This is a portrait of Iris Clert if I say so”. What then is this movement in/of reading? Following Blanchot, we might think it as a movement of detour, which The Infinite Conversation locates in relation to the question: “Every true question opens onto the whole of questions… But now we see that there is in it, more “profoundly,” a detour that diverts questioning from being able to be a question, and from being able to bring about an answer.”3 The detour for Blanchot is labyrinthine: the question contains a detour away from itself; speech itself is a detour in which the question slips away; the question is a detour that speaks through the detour of speech. -

Transition Magazine 1927-1930

i ^ p f f i b A I Writing and art from transition magazine 1927-1930 CONTRIBUTIONS BY SAMUEL BECKETT PAUL BOWLES KAY BOYLE GEORGES BRAQUE ALEXANDER CALDER HART CRANE GIORGIO DE CHIRICO ANDRE GIDE ROBERT GRAVES ERNEST HEMINGWAY JAMES JOYCE C.G. JUNG FRANZ KAFKA PAUL KLEE ARCHIBALD MACLEISH MAN RAY JOAN MIRO PABLO PICASSO KATHERINE ANNE PORTER RAINER MARIA RILKE DIEGO RIVERA GERTRUDE STEIN TRISTAN TZARA WILLIAM CARLOS WILLIAMS AND OTHERS ■ m i , . « f " li jf IT ) r> ’ j vjffjiStl ‘■vv ■H H Iir ■ nr ¥ \I ififl $ 14.95 $388 in transition: A Paris Anthology IK i\ Paris transition An Anthology transition: A Paris Anthology WRITING AND ART FROM transition MAGAZINE 1927-30 With an Introduction by Noel Riley Fitch Contributions by Samuel BECKETT, Paul BOWLES, Kay BOYLE, Georges BRAQUE, Alexander CALDER, Hart CRANE, Giorgio DE CHIRICO, Andre GIDE, Robert GRAVES, Ernest HEMINGWAY, James JOYCE, C. G. JUNG, Franz KAFKA, Paul KLEE, Archibald MacLEISH, MAN RAY, Joan MIRO, Pablo PICASSO, Katherine Anne PORTER, Rainer Maria RILKE, Diego RIVERA, Gertrude STEIN, Tristan TZARA, William Carlos WILLIAMS and others A n c h o r B o o k s DOUBLEDAY NEW YORK LONDON TORONTO SYDNEY AUCKLAND A n A n c h o r B o o k PUBLISHED BY DOUBLEDAY a division of Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc. 666 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10103 A n c h o r B o o k s , D o u b l e d a y , and the portrayal of an anchor are trademarks of Doubleday, a division of B antam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc. -

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art

This page intentionally left blank This page intentionally left blank A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 2 Painters born from 1850 to 1910 This page intentionally left blank A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 2 Painters born from 1850 to 1910 by Dorothy W. Phillips Curator of Collections The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.G. 1973 Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number N 850. A 617 Designed by Graham Johnson/Lund Humphries Printed in Great Britain by Lund Humphries Contents Foreword by Roy Slade, Director vi Introduction by Hermann Warner Williams, Jr., Director Emeritus vii Acknowledgments ix Notes on the Catalogue x Catalogue i Index of titles and artists 199 This page intentionally left blank Foreword As Director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, I am pleased that Volume II of the Catalogue of the American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art, which has been in preparation for some five years, has come to fruition in my tenure. The second volume deals with the paintings of artists born between 1850 and 1910. The documented catalogue of the Corcoran's American paintings carries forward the project, initiated by former Director Hermann Warner Williams, Jr., of providing a series of defini• tive publications of the Gallery's considerable collection of American art. The Gallery intends to continue with other volumes devoted to contemporary American painting, sculpture, drawings, watercolors and prints. In recent years the growing interest in and concern for American paint• ing has become apparent. -

2018–2019 MFAH Annual Report

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston annual report 2018–2019 MFAH BY THE NUMBERS July 1, 2018 –June 30, 2019 Attendance • visits to the Museum, the Lillie and Hugh 1,269,626 $6.4 Tuition Roy Cullen Sculpture Garden, Bayou Bend Collection 9% Other Revenue $10.7 and Gardens, Rienzi, and the Glassell School of Art $2.4 14% 3% Membership • 101,971 visitors and students reached through learning Revenue $3.4 and interpretation programs on-site and off-site 5% FY 2019 • 77,821 youth visitors ages 18 and under received free Operating Revenues Endowment or discounted access to the MFAH Operating (millions) Spending Fund-raising $37.5 $14.2 50% • 37,986 schoolchildren and their chaperones received 19% free or discounted tours of the MFAH • 7,969 Houstonians were served through community engagement programs off-site Total Revenues: $74.6 million • 118 community partners citywide collaborated with the MFAH Exhibitions, Curatorial, and Collections $14.8 Auxiliary 22% • 3,439,718 visits recorded at mfah.org Activities $4.6 7% • 442,416 visits recorded at the online collections module Fund-raising $6.3 9% • 346,400 people followed the MFAH on Facebook, FY 2019 Education, Libraries, Instagram, and Twitter Operating Expenses and Visitor (millions) Engagment $14.7 22% • 316,229 online visitors accessed the Documents of 20th-Century Latin American and Latino Art Website, icaadocs.mfah.org Management and General $9.6 Buildings and Grounds 14% and Security $17.5 • 234,649 visits to Vincent van Gogh: His LIfe in Art 26% Total Expenses: $67.5 million • 87,934 individuals -

June 1978 SC^ Monthly for the Press Ce the Museum of Modern Art ^ 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y

TIGHT BINDING e AJ* June 1978 SC^ Monthly for the Press ce The Museum of Modern Art ^ 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Department of Public Information, (212)956-2648 What' s New Page 1 What's Coming Up Page 2 Current Exhibitions Page 3-4 Gal 1 ery Tal ks, Speci al Events Page 5 Ongoing, Museum Hours Page 6 New Film Series, Continuing Film Series Page 7 WHAT'S NEW ETCHINGS Jim Pine's Etchings Jim 6—Sep 5 One hundred prints trace the history of Dine's work in etching, exploring his imagery and techniques. In his first drypoints, Dine brought a fresh and imaginative attitude to printmaking, directly relating this work to his "happenings" and construc tion/canvases. He was one of the first to return to the ol^. art of hand-coloring prints, thereby producing a body of work of infinite variety. His most recent work has an expressive, tor tured character that expands and may reorient ideas regarding Dine's art and that of his generation. (East Wing, 1st floor) SOUND INSTALLATION Max Neuhaus June 8—Sep This is the second in a series of sound installations, the first of which was installed beneath a pedestrian island in Times Square where a deep, rich texture of sound was generated from beneath a subway grating, and transformed the aural environment for pedestrians. In contrast, the Museum's installation is located in the quiet of the Sculpture Garden, with sound generated from within a ventilation chamber running along the East Wing of the Museum. -

New Acquisitions Paintings

NEW ACQUISITIONS PAINTINGS, WATERCOLORS, DRAWINGS AND SCULPTURE 1780 – 1960 FALL EXHIBITION October 23 rd through December 15 th, 2012 Exhibition organized by Robert Kashey and David Wojciechowski Catalog by Jennifer S. Brown SHEPHERD & DEROM GALLERIES 58 East 79 th Street New York, N. Y. 10075 Tel: 1 212 861 4050 Fax: 1 212 772 1314 [email protected] www.shepherdgallery.com CATALOG © Copyright: Robert J. F. Kashey for Shepherd Gallery, Associates, 20 12 COVER ILLUSTRATION: Hermann August Krause, Interior View of the Lessing Theatre, Berlin , 1888, cat. no. 14. GRAPHIC DESIGN: Keith Stout PHOTOGRAPHY: Hisao Oka TECHNICAL NOTES: All measurements are in inches and in centimeters; height precedes width. All drawings and paintings are framed. Prices on request. All works subject to prior sale. SHEPHERD GALLERY SERVICES has framed, matted, and restored all of the objects in this exhibition, if required. The Service Department is open to the public by appointment, Tuesday through Saturday from 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Tel: (212) 744 3392; fax (212) 744 1525; e-mail: [email protected]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: We are grateful to the following for their assistance with individual catalog entries: Charles Chatfield-Taylor, catalog nos. 29, 30, 31 Elisabeth Kashey, catalog nos. 2, 3, 15, 18, 26 Leanne M. Zalewski, catalog nos. 12, 41 1 SMITH, John “Warwick” 1749 - 1831 English School VIEW OF THE LAKE AT WALENSTADT, 1781 Reed pen, grey ink and washes on mediumweight white Smith and Towne spent the summer of 1781 laid paper. No discernible watermark. 6” x 9 5/8” (15.3 x traveling together from Italy to England via an 24.4 cm). -

A Magazine of Verse Edited by Harriet Monroe October 1920

Vol. XVII No. I A Magazine of Verse Edited by Harriet Monroe October 1920 Down the Mississippi by John Gould Fletcher A Town on the River by Laura Sherry America—1919 by Isidor Schneider 543 Cass Street, Chicago $3.00 per Year Single Numbers 25c Splendidly edited. Invaluable to those who would keep in touch with mod ern poetry. "Point of departure from conservatism may be dated from the establishment of POETRY" (Braithwaite). From Classified List of Contemporary Poets compiled for libraries by Anne Morris Boyd, A. B., B. L. S. Vol. XVII No. I POETRY for OCTOBER, 1920 PAGE Down the Mississippi John Gould Fletcher 1 Embarkation — Heat—Full Moon — The Moon's Orchestra —The Stevedores—Night Landing—The Silence A Town on the River Laura Sherry 6 My Town—On Our Farm—The Hunter—A Woodsman— Jean Joseph Rolette—Louis des Chiens—Bohemian Town The Corn-field Charles R. Murphy 13 Tosti's Goodbye Walter McClellan 14 Fantasy A. A. Rosenthal 15 Adoration Hazel C. Hutchison 15 The Gypsy Beatrice Ravenel 16 Life Everlasting Esther A. Whitmarsh 17 Waves—Beauty Louise Towmsend Nicholl 18 To One Beloved Glenn Ward Dresbach 19 The Last Lady Matthew Josephson 20 The Pelican Alice Louise Jones 21 Gospel with Banjo and Chorus Keene Wallis 22 America—1919 Isidor Schneider 24 A Hymn for the Lynchers—A Memory—The Heroes Frugality and Deprecation H. M. 30 The Disciples of Gertrude Stein . Richard Aldington 35 Reviews : Camouflage H. M. 40 Flint and Rodker Richard Aldington 44 Three Poets of Three Nations . Emanuel Carnevali 48 Argentine Drama Evelyn Scott 52 Correspondence Disarmament Morris Bishop 55 Modern Poetry at the Ü.