A Magazine of Verse Edited by Harriet Monroe October 1920

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walter Hasenclever

Gregor Ackermann Walter Hasenclever Weitere Hinweise zur Überlieferung seiner Werke Eine Handreichung für seine Leserinnen und Leser . JUNI ONLINES 4 Mönchengladbach 2020 Impressum: JUNI ONLINES werden herausgegeben von Gregor Ackermann und Walter Delabar. Sie sind ausschließlich auf der Website des JUNI Magazins erhältlich und liegen ansonsten nicht im Druck vor. Sie dürfen unentgeltlich heruntergeladen und verwendet werden. Wir bitten bei Verwendung um den eindeutigen Quellenverweis mit Verweis auf die Bezugsquelle (www.juni-magazin.de). Alle Rechte liegen bei den Autoren: © Gregor Ackermann. Zitieren Sie JUNI ONLINES 4 bitte folgendermaßen: Gregor Ackermann: Walter Hasenclever. Weitere Hinweise zur Überlieferung seiner Werke Mönchengladbach 2020 (JUNI ONLINES 4). Auf: juni-magazin.de/Onlines (Datum des Zugriffs). Mönchengladbach, den 28. August 2020 2 Walter Hasenclever Weitere Hinweise zur Überlieferung seiner Werke Eine Handreichung für seine Leserinnen und Leser Die nachfolgenden Hinweise ergänzen und korrigieren die in Hasenclevers Sämtlichen Werken dokumentierte Drucküberlieferung und die kleine Broschüre des Verfassers aus dem Jahr 2015. Erfasst werden nun auch postume Übersetzungen von Hasenclevers Werken; die Berichterstattung wird sukzessive bis in die Gegenwart fortgeführt. Nicht berücksichtigt werden hierbei Unterrichtswerke für den Schulgebrauch und die Angebote der elektronischen Zweit- und Drittverwerter. Beigefügt wurden Nachweise von Adaptionen (zumeist für den Rundfunk), Lesungen im Rundfunk und Verfilmungen. Das Verzeichnis der Autografen wird fortgeschrieben. (Stand: 21. Oktober 2019) Eine Publikation war zum jetzigen Zeitpunkt nicht vorgesehen. Nur äußere Umstände bedingten eine vielleicht voreilige Veröffentlichung. Dank an Stephan Berelsmann, Hans-Joachim Heerde, Dirk Heißerer, Ariane Martin, Ursula Marx, Rainer-Joachim Siegel und Bernhard Veitenheimer für freundliche Hinweise und Unterstützungen. Siglen * = Keine Autopsie. Biographie = Bert Kasties: Walter Hasenclever. -

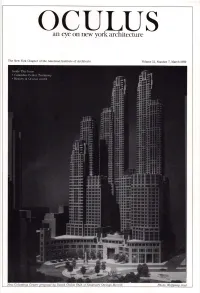

An Eye on New York Architecture

OCULUS an eye on new york architecture The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 ew Co lumbus Center proposal by David Childs FAIA of Skidmore Owings Merrill. 2 YC/AIA OC LUS OCULUS COMING CHAPTER EVENTS Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 Oculus Tuesday, March 7. The Associates Tuesday, March 21 is Architects Lobby Acting Editor: Marian Page Committee is sponsoring a discussion on Day in Albany. The Chapter is providing Art Director: Abigail Sturges Typesetting: Steintype, Inc. Gordan Matta-Clark Trained as an bus service, which will leave the Urban Printer: The Nugent Organization architect, son of the surrealist Matta, Center at 7 am. To reserve a seat: Photographer: Stan Ri es Matta-Clark was at the center of the 838-9670. avant-garde at the end of the '60s and The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects into the '70s. Art Historian Robert Tuesday, March 28. The Chapter is 457 Madison Avenue Pincus-Witten will be moderator of the co-sponsoring with the Italian Marble New York , New York 10022 evening. 6 pm. The Urban Center. Center a seminar on "Stone for Building 212-838-9670 838-9670. Exteriors: Designing, Specifying and Executive Committee 1988-89 Installing." 5:30-7:30 pm. The Urban Martin D. Raab FAIA, President Tuesday, March 14. The Art and Center. 838-9670. Denis G. Kuhn AIA, First Vice President Architecture and the Architects in David Castro-Blanco FAIA, Vice President Education Committees are co Tuesday, March 28. The Professional Douglas Korves AIA, Vice President Stephen P. -

Genius Is Nothing but an Extravagant Manifestation of the Body. — Arthur Cravan, 1914

1 ........................................... The Baroness and Neurasthenic Art History Genius is nothing but an extravagant manifestation of the body. — Arthur Cravan, 1914 Some people think the women are the cause of [artistic] modernism, whatever that is. — New York Evening Sun, 1917 I hear “New York” has gone mad about “Dada,” and that the most exotic and worthless review is being concocted by Man Ray and Duchamp. What next! This is worse than The Baroness. By the way I like the way the discovery has suddenly been made that she has all along been, unconsciously, a Dadaist. I cannot figure out just what Dadaism is beyond an insane jumble of the four winds, the six senses, and plum pudding. But if the Baroness is to be a keystone for it,—then I think I can possibly know when it is coming and avoid it. — Hart Crane, c. 1920 Paris has had Dada for five years, and we have had Else von Freytag-Loringhoven for quite two years. But great minds think alike and great natural truths force themselves into cognition at vastly separated spots. In Else von Freytag-Loringhoven Paris is mystically united [with] New York. — John Rodker, 1920 My mind is one rebellion. Permit me, oh permit me to rebel! — Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, c. 19251 In a 1921 letter from Man Ray, New York artist, to Tristan Tzara, the Romanian poet who had spearheaded the spread of Dada to Paris, the “shit” of Dada being sent across the sea (“merdelamerdelamerdela . .”) is illustrated by the naked body of German expatriate the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (see fig. -

The New Age Under Orage

THE NEW AGE UNDER ORAGE CHAPTERS IN ENGLISH CULTURAL HISTORY by WALLACE MARTIN MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS BARNES & NOBLE, INC., NEW YORK Frontispiece A. R. ORAGE © 1967 Wallace Martin All rights reserved MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS 316-324 Oxford Road, Manchester 13, England U.S.A. BARNES & NOBLE, INC. 105 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10003 Printed in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner Ltd, Frome and London This digital edition has been produced by the Modernist Journals Project with the permission of Wallace T. Martin, granted on 28 July 1999. Users may download and reproduce any of these pages, provided that proper credit is given the author and the Project. FOR MY PARENTS CONTENTS PART ONE. ORIGINS Page I. Introduction: The New Age and its Contemporaries 1 II. The Purchase of The New Age 17 III. Orage’s Editorial Methods 32 PART TWO. ‘THE NEW AGE’, 1908-1910: LITERARY REALISM AND THE SOCIAL REVOLUTION IV. The ‘New Drama’ 61 V. The Realistic Novel 81 VI. The Rejection of Realism 108 PART THREE. 1911-1914: NEW DIRECTIONS VII. Contributors and Contents 120 VIII. The Cultural Awakening 128 IX. The Origins of Imagism 145 X. Other Movements 182 PART FOUR. 1915-1918: THE SEARCH FOR VALUES XI. Guild Socialism 193 XII. A Conservative Philosophy 212 XIII. Orage’s Literary Criticism 235 PART FIVE. 1919-1922: SOCIAL CREDIT AND MYSTICISM XIV. The Economic Crisis 266 XV. Orage’s Religious Quest 284 Appendix: Contributors to The New Age 295 Index 297 vii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS A. R. Orage Frontispiece 1 * Tom Titt: Mr G. Bernard Shaw 25 2 * Tom Titt: Mr G. -

Sophocles' Antigone Reworked in the Twentieth

NEW VOICES IN CLASSICAL RECEPTION STUDIES Issue 12 (2018) SOPHOCLES’ ANTIGONE REWORKED IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: THE CASE OF HASENCLEVER’S ANTIGONE (1917) © Rossana Zetti (University of Edinburgh) INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXTUALIZATION This article examines a little-known example of Antigone’s reception in the twentieth century: the adaptation by the German expressionist writer Walter Hasenclever. This version is the first and arguably most innovative of several European adaptations of Sophocles’ play to appear in the first half of the twentieth century. Although successful at the time of its production, Hasenclever’s Antigone is scarcely read in contemporary scholarship and is discussed mainly in German-language scholarship.1 Whereas Flashar’s wide-ranging study, in German, refers to Hasenclever’s drama (Flashar 2009: 127– 29), in Fischer-Lichte’s 2017 book Tragedy’s Endurance, in English, Hasenclever appears only in one endnote (Fischer-Lichte 2017: 143). The only English translation of the play available (Ritchie and Stowell 1969: 113–60) is rather out of date and inaccessible. Hasenclever’s Antigone is briefly mentioned in Steiner’s essential reference book Antigones (Steiner 1984: 142; 146; 170; 218), in the chapter on Antigone in the recent Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Sophocles (Silva 2017: 406–7) and in Cairns’ 2016 book on Sophocles’ Antigone (Cairns 2016: 133). However, it is absent in some of the most recent contributions dedicated to the play’s modern reception, including Wilmer’s and Žukauskaitė’s edited collection on Antigone in postmodern thought (2010), Mee’s and Foley’s essays (2011) discussing adaptations of Antigone staged around the world, and Morais’, Hardwick’s and Silva’s recent volume (2017).2 The absence of Hasenclever from contemporary scholarship can be explained by the fact that his Antigone lacks the complexity of later adaptations, such as Anouilh’s and Brecht’s. -

Cinematic Vitalism Film Theory and the Question of Life

INGA POLLMANN INGA FILM THEORY FILM THEORY IN MEDIA HISTORY IN MEDIA HISTORY CINEMATIC VITALISM FILM THEORY AND THE QUESTION OF LIFE INGA POLLMANN CINEMATIC VITALISM Cinematic Vitalism: Film Theory and the INGA POLLMANN is Assistant Professor Question of Life argues that there are in Film Studies in the Department of Ger- constitutive links between early twen- manic and Slavic Languages and Litera- tieth-century German and French film tures at the University of North Carolina theory and practice, on the one hand, at Chapel Hill. and vitalist conceptions of life in biology and philosophy, on the other. By consi- dering classical film-theoretical texts and their filmic objects in the light of vitalist ideas percolating in scientific and philosophical texts of the time, Cine- matic Vitalism reveals the formation of a modernist, experimental and cinema- tic strand of vitalism in and around the movie theater. The book focuses on the key concepts rhythm, environment, mood, and development to show how the cinematic vitalism articulated by film theorists and filmmakers maps out connections among human beings, mi- lieus, and technologies that continue to structure our understanding of film. ISBN 978-94-629-8365-6 AUP.nl 9 789462 983656 AUP_FtMh_POLLMANN_(cinematicvitalism)_rug17.7mm_v02.indd 1 21-02-18 13:05 Cinematic Vitalism Film Theory in Media History Film Theory in Media History explores the epistemological and theoretical foundations of the study of film through texts by classical authors as well as anthologies and monographs on key issues and developments in film theory. Adopting a historical perspective, but with a firm eye to the further development of the field, the series provides a platform for ground-breaking new research into film theory and media history and features high-profile editorial projects that offer resources for teaching and scholarship. -

A MEDIUM for MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY and AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997

A MEDIUM FOR MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY AND AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997 CASE 1 1. Photograph of Harriet Monroe. 1914. Archival Photographic Files Harriet Monroe (1860-1936) was born in Chicago and pursued a career as a journalist, art critic, and poet. In 1889 she wrote the verse for the opening of the Auditorium Theater, and in 1893 she was commissioned to compose the dedicatory ode for the World’s Columbian Exposition. Monroe’s difficulties finding publishers and readers for her work led her to establish Poetry: A Magazine of Verse to publish and encourage appreciation for the best new writing. 2. Joan Fitzgerald (b. 1930). Bronze head of Ezra Pound. Venice, 1963. On Loan from Richard G. Stern This portrait head was made from life by the American artist Joan Fitzgerald in the winter and spring of 1963. Pound was then living in Venice, where Fitzgerald had moved to take advantage of a foundry which cast her work. Fitzgerald made another, somewhat more abstract, head of Pound, which is in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Pound preferred this version, now in the collection of Richard G. Stern. Pound’s last years were lived in the political shadows cast by his indictment for treason because of the broadcasts he made from Italy during the war years. Pound was returned to the United States in 1945; he was declared unfit to stand trial on grounds of insanity and confined to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for thirteen years. Stern’s novel Stitch (1965) contains a fictional account of some of these events. -

In the Realm of Politics, Nonsense, and the Absurd: the Myth of Antigone in West and South Slavic Drama in the Mid-Twentieth Century

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4312/keria.20.3.95-108 Alenka Jensterle-Doležal In the Realm of Politics, Nonsense, and the Absurd: The Myth of Antigone in West and South Slavic Drama in the Mid-Twentieth Century Throughout history humans have always felt the need to create myths and legends to explain and interpret human existence. One of the classical mythi- cal figures is ancient Antigone in her torment over whether to obey human or divine law. This myth is one of the most influential myths in European literary history. In the creation of literature based on this myth there have always been different methods and styles of interpretation. Literary scholars always emphasised its philosophical and anthropological dimensions.1 The first variants of the myth of Antigone are of ancient origin: the playAntigone by Sophocles (written around 441 BC) was a model for others throughout cultural and literary history.2 There are various approaches to the play, but the well-established central theme deals with one question: the heroine Antigone is deeply convinced that she has the right to reject society’s infringement on her freedom and to act, to recognise her familial duty, and not to leave her brother’s body unburied on the battlefield. She has a personal obligation: she must bury her brother Polyneikes against the law of Creon, who represents the state. In Sophocles’ play it is Antigone’s stubbornness transmitted into action 1 Cf. also: Simone Fraisse, Le mythe d’Antigone (Paris: A. Colin, 1974); Cesare Molinari, Storia di Antigone da Sofocle al Living theatre: un mito nel teatro occidentale (Bari: De Donato, 1977); George Steiner, Antigones (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984); Elisabeth Frenzel, Stoffe der Weltlitera- tur: Ein Lexikon Dichtungsgeschichtlicher Längsschnitte, 5. -

The Flâneuse's Old Age

Universiteit Gent Academiejaar 2005 Women’s Passages: A Bildungsroman of Female Flânerie Verhandeling voorgelegd aan de Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte Promotor: Prof. Dr. Bart Keunen voor het verkrijgen van de graad van licentiaat in de taal- en letterkunde: Germaanse Talen, door (Karen Van Godtsenhoven). Credits: The writing of a dissertation requires a lot more than just a computer and books: apart from the many material and practical necessities, there still are many personal and difficult-to- trace advices, inspiring conversations and cityscapes that have helped me writing this little volume. This list cannot be inclusive, but I can try to track down the most relevant people, in their most relevant environment (in the line of the following chapters…). First of all, I want to thank all the people of the University of Ghent, for their help and interest from the very beginning. My promotor, Prof. Bart Keunen, wins the first prize for valuable advice and endless patience with my writings and my person. Other professors and teachers like Claire Vandamme, Bart Eeckhout, Elke Gilson and Katrien De Moor were good mentors and gave me lots of reading material and titles. From my former universities, I want to thank Prof. Martine de Clercq (KUBrussel) who helped me putting things together in an inspiring way. Other thank you’s go to Prof. Kate McGowan (Critical and Cultural Theory) and Prof. Angela Michaelis (Culture of Decadence) from the Manchester Metropolitan University, who gave me a more academic basis for my interest in the subject of this dissertation. I want to thank Petra Broeders from Passaporta in Brussels for lending me books and providing me with coffee, Guido Fourrier from the Fashion Museum in Hasselt for his refreshing tour of the A la Garçonne exhibition, the people from Rosa in Brussels for explaining me several gender issues, and Belle and Carolien from DASQ (Ghent) for their “decadent” literature salons where I had the opportunity to listen and talk to Denise De Weerdt. -

KOPF – Eigentümer / Verwalter

Fachbereich Presse und Marketing Der Oberbürgermeister Presseinformation Robert Menasse mit dem Walter-Hasenclever-Literaturpreis Info 1412/18 ausgezeichnet Der Wiener Schriftsteller und Essayist erhält den Preis für sein Gesamtwerk und seine konkrete Vision einer „konsequent Währung, Wirtschaft und Politik einschließenden Europäischen Union.“ Oberbürgermeister Marcel Philipp würdigt Menasse als aufrechten Kämpfer gegen den Nationalismus. In einer ergreifenden Rede äußert der Preisträger seine Sorgen um die Lage Europas. Der Wiener Schriftsteller und Essayist Robert Menasse hat am Sonntag, 18. November, den Walter-Hasenclever-Literaturpreis der Stadt Aachen erhalten. Bei der festlichen Preisverleihung vor etwa 250 Zuhörern im Ludwig Forum ging es allen Rednern vor allem um die Lage Europas – einem zentralen Thema in Menasses Werk. Die Jury würdigte in ihrer Begründung das Gesamtwerk des Autors und dessen konkrete Vision einer „konsequent Währung, Wirtschaft und Politik einschließenden Europäischen Union.“ Menasse setze sich in seinen Essays verstärkt für eine gesamteuropäische Idee ein und stelle sich entschieden gegen nationale Interessen. Gerade in der heutigen Zeit, mit dem Aufschwung von nationalistischen Bewegungen in ganz Europa, sei eine entschiedene Stimme wie die des Österreichers besonders wertvoll. Aufrechter Kämpfer gegen Antieuropäer Erst vor acht Tagen ließ Menasse in einer gemeinsamen Kunstaktion mit Ulrike Guérot ein von ihnen verfasstes „Manifest zur Ausrufung der Europäischen Datum: Haus Löwenstein, Markt 39 19.11.2018 -

Table of Contents

Contents Acknowledgments xiii User’s Guide xv Introduction 1 SECTION ONE. TRANSFORMATIONS OF EXPERIENCE 1. A New Sensorium 1. Hanns Heinz Ewers, The Kientopp (1907) 13 2. Max Brod, Cinematographic Theater (1909) 15 3. Gustav Melcher, On Living Photography and the Film Drama (1909) 17 4. Kurt Weisse, A New Task for the Cinema (1909) 20 5. Anon., New Terrain for Cinematographic Theaters (1910) 22 6. Anon., The Career of the Cinematograph (1910) 22 7. Karl Hans Strobl, The Cinematograph (1911) 25 8. Ph. Sommer, On the Psychology of the Cinematograph (1911) 28 9. Hermann Kienzl, Theater and Cinematograph (1911) 30 10. Adolf Sellmann, The Secret of the Cinema (1912) 31 11. Arno Arndt, Sports on Film (1912) 33 12. Carl Forch, Thrills in Film Drama and Elsewhere (1912–13) 35 13. Lou Andreas-Salomé, Cinema (1912–13) 38 14. Walter Hasenclever, The Kintopp as Educator: An Apology (1913) 39 15. Walter Serner, Cinema and Visual Pleasure (1913) 41 16. Albert Hellwig, Illusions and Hallucinations during Cinematographic Projections (1914) 45 2. The World in Motion 17. H. Ste., The Cinematograph in the Service of Ethnology (1907) 48 18. O. Th. Stein, The Cinematograph as Modern Newspaper (1913–14) 49 19. Hermann Häfker, Cinema and Geography: Introduction (1914) 51 20. Yvan Goll, The Cinedram (1920) 52 21. Hans Schomburgk, Africa and Film (1922) 55 22. Franc Cornel, The Value of the Adventure Film (1923) 56 23. Béla Balázs, Reel Consciousness (1925) 58 24. Colin Ross, Exotic Journeys with a Camera (1928) 60 25. Anon., Lunar Flight in Film (1929) 62 26. -

BRYANT PARK in Celebration of Gabriel Kreuther's Second

christian boone BRYANT PARK In celebration of Gabriel Kreuther’s second anniversary and the 25th anniversary of Bryant Park as we know it today, we are delighted to present to you a cocktail menu that will allow you to travel through the history of our community and discover the secrets of the park and the New York public. Potter’s Field Illegal Mezcal • Lillet Blanc • St-Germain • Black Cardamom • Lemon ~ One of the first known uses for Bryant Park was as a potter’s field in 1823; its purpose was a graveyard for society’s solitary and indigent. It remained so until 1840, when the city decommissioned it and thousands of bodies were moved to Wards Island in prepara- tion for the construction of the Croton Reservoir. The Reservoir Ketel One Vodka • Red Pepper • Oregano • Lemon • Absinthe ~ The Croton Distributing Reservoir was surrounded by 50-foot high, thick granite walls and supplied the city with drinking water during the 19th century. Along the tops of the walls were public promenades where Edgar Allan Poe enjoyed his walks. A remnant of the reservoir can still be seen today in the New York Public Library. Washington’s Troop Michter’s Rye • Massenez Crème de Pêche • Apricot • Lemon • Rosemary ~ General George Washington solemnly crossed the park with his troops after suffering a defeat at the battle of Brooklyn in 1776, the first major battle of the war to take place after America declared independence on July 4th, 1776. After the battle, the British held CHAPTER I New York City for the remainder of the Revolutionary War.