Datapoint Oral History Panel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Telecom Meltdown for a Listing of Recent Titles in the Artech House Telecommunications Library, Turn to the Back of This Book

The Great Telecom Meltdown For a listing of recent titles in the Artech House Telecommunications Library, turn to the back of this book. The Great Telecom Meltdown Fred R. Goldstein a r techhouse. com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the U.S. Library of Congress. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Goldstein, Fred R. The great telecom meltdown.—(Artech House telecommunications Library) 1. Telecommunication—History 2. Telecommunciation—Technological innovations— History 3. Telecommunication—Finance—History I. Title 384’.09 ISBN 1-58053-939-4 Cover design by Leslie Genser © 2005 ARTECH HOUSE, INC. 685 Canton Street Norwood, MA 02062 All rights reserved. Printed and bound in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. All terms mentioned in this book that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Artech House cannot attest to the accuracy of this information. Use of a term in this book should not be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. International Standard Book Number: 1-58053-939-4 10987654321 Contents ix Hybrid Fiber-Coax (HFC) Gave Cable Providers an Advantage on “Triple Play” 122 RBOCs Took the Threat Seriously 123 Hybrid Fiber-Coax Is Developed 123 Cable Modems -

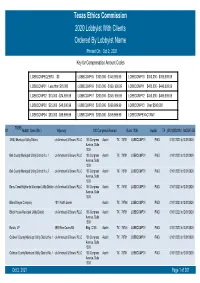

Texas Ethics Commission 2020 Lobbyist with Clients Ordered by Lobbyist Name Printed on Oct 2, 2021 Key for Compensation Amount Codes

Texas Ethics Commission 2020 Lobbyist With Clients Ordered By Lobbyist Name Printed On Oct 2, 2021 Key for Compensation Amount Codes LOBBCOMPEQZERO $0 LOBBCOMP05 $100,000 - $149,999.99 LOBBCOMP10 $350,000 - $399,999.99 LOBBCOMP01 Less than $10,000 LOBBCOMP06 $150,000 - $199, 999.99 LOBBCOMP11 $400,000 - $449,999.99 LOBBCOMP02 $10,000 - $24,999.99 LOBBCOMP07 $200,000 - $249, 999.99 LOBBCOMP12 $450,000 - $499,999.99 LOBBCOMP03 $25,000 - $49,000.99 LOBBCOMP08 $250,000 - $299,999.99 LOBBCOMP13 Over $500,000 LOBBCOMP04 $50,000 - $99,999.99 LOBBCOMP09 $300,000 - $349,999.99 LOBBCOMPEXACTAMT 70358 #1 Abbott, Sean (Mr.) Attorney 100 Congress Avenue Suite 1300 Austin TX (512)4352334 MODIFIED 3 B&J Municipal Utility District c/o Armbrust & Brown, PLLC 100 Congress Austin TX 78701 LOBBCOMP01 PAID 01/01/2020 to12/31/2020 Avenue, Suite 1300 Bell County Municipal Utility District No. 1 c/o Armbrust & Brown, PLLC 100 Congress Austin TX 78701 LOBBCOMP01 PAID 01/01/2020 to12/31/2020 Avenue, Suite 1300 Bell County Municipal Utility District No. 2 c/o Armbrust & Brown, PLLC 100 Congress Austin TX 78701 LOBBCOMP01 PAID 01/01/2020 to12/31/2020 Avenue, Suite 1300 Berry Creek Highlands Municipal Utility District c/o Armbrust & Brown, PLLC 100 Congress Austin TX 78701 LOBBCOMP01 PAID 01/01/2020 to12/31/2020 Avenue, Suite 1300 Blake Magee Company 1011 North Lamar Austin TX 78704 LOBBCOMP01 PAID 01/01/2020 to12/31/2020 Block House Municipal Utility District c/o Armbrust & Brown, PLLC 100 Congress Austin TX 78701 LOBBCOMP01 PAID 01/01/2020 to12/31/2020 Avenue, Suite 1300 Bonzo, LP 3939 Bee Caves Rd. -

Microcomputers: NQS PUBLICATIONS Introduction to Features and Uses

of Commerce Computer Science National Bureau and Technology of Standards NBS Special Publication 500-110 Microcomputers: NQS PUBLICATIONS Introduction to Features and Uses QO IGf) .U57 500-110 NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards' was established by an act ot Congress on March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides; (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to promote public safety. The Bureau's technical work is per- formed by the National Measurement Laboratory, the National Engineering Laboratory, and the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology. THE NATIONAL MEASUREMENT LABORATORY provides the national system of physical and chemical and materials measurement; coordinates the system with measurement systems of other nations and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical and chemical measurement throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce; conducts materials research leading to improved methods of measurement, standards, and data on the properties of materials needed by industry, commerce, educational institutions, and Government; provides advisory and research services to other Government agencies; develops, produces, and -

The State Board of Education

THE STAte OF the RELIGIOUS RIGht { 2008 } THE STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION: DRAGGING TEXAS SCHOOLS INTO THE CULTURE WARS THE STAte OF the RELIGIOUS RIGht { 2008 } THE STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION: DRAGGING TEXAS SCHOOLS INTO THE CULTURE WARS A R E p ort f ro m the T exas f R E E D O m N etwor k E ducation f U N D kathy miller, TFN president Dan Quinn, TFN communications director Bren Gorman, researcher Judie Niskala, researcher Emily Sentilles, researcher A bout the T f N E ducation f U N D The Texas Freedom Network Education Fund is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt, nonprofit corporation. Created in 1996, the TFN Education Fund researches the agenda, activities and funding of the religious right. It also educates mainstream people of faith in how to formulate and to advocate a faith-based response to the religious right’s policy agenda. TfN Education fund Board of Directors Rebecca Lightsey, chair Janis pinnelli, treasurer Rev. Dr. Larry Bethune Grace Garcia Diane Ireson Dale Linebarger Table Of Contents Introduction. .2. Watch List: 2008. .5 1: The State Board of Education in Texas. .11 2: A History of Censorship in Texas. .17 3: The Right Ascendant. 21 4: Targeting Curriculum Standards (TEKS). .25 Appendices Appendix A: Who’s Who in Texas Textbook Censorship . .30 Appendix B: Textbook Censorship in Texas: A Timeline. .32 Appendix C: Textbook Censorship in Texas: The Record. .35 Appendix D: They Really Said It: Quoting the Religious Right in 2007 .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ...36 Appendix E: Organizations of the Religious Right in Texas. -

Assessment of Data Rates on the Internal and External Cpu Interfaces and Its Applications for Wireless Network-On-Chip Development

MARIIA KOMAR ASSESSMENT OF DATA RATES ON THE INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL CPU INTERFACES AND ITS APPLICATIONS FOR WIRELESS NETWORK-ON-CHIP DEVELOPMENT Master of Science thesis Examiner: Prof. Yevgeni Koucheryavy, Dr. Dmitri Moltchanov Examiner and topic approved by the Faculty Council of the Faculty of Computing and Electrical Engineering on 27th September 2017 I ABSTRACT MARIIA KOMAR: Assessment of data rates on the internal and external CPU interfaces and its applications for Wireless Network-on-Chip development Tampere University of Technology Master of Science thesis, 56 pages November 2017 Master's Degree Programme in Information Technology Major: Information Technology Examiner: Prof. Yevgeni Koucheryavy, Dr. Dmitri Moltchanov Keywords: central processing unit, CPU, CPU performance, Wireless Networks-on-Chip, WNoC, data rates assessment Nowadays central processing units (CPUs) are the major part of the personal com- puters, and usually their progress denes personal computers (PCs) progress. How- ever, modern CPU architecture has a set of limitations mentioned in this thesis. As a result, new CPU architectures are now under development. Most prospective solution in this eld are based on a proposed concept of Wireless Networks-on-Chip (WNoCs), where part of wired connections is changed into wireless links. However in order to design and develop this kind of system, information about data rates on the internal and external CPU interfaces of modern CPUs is needed. Main goals set in the beginning of working on this thesis were to get this data rates assessment and give an assessment of suitable wireless technologies for milticore CPUs with dierent number of cores. In this thesis CPU evolution is described and peculiarities of modern CPU archi- tectures are mentioned. -

Low Cost Video for Distance Education Michael J

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks CEC Theses and Dissertations College of Engineering and Computing 1996 Low Cost Video For Distance Education Michael J. Simpson Nova Southeastern University, [email protected] This document is a product of extensive research conducted at the Nova Southeastern University College of Engineering and Computing. For more information on research and degree programs at the NSU College of Engineering and Computing, please click here. Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/gscis_etd Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Share Feedback About This Item NSUWorks Citation Michael J. Simpson. 1996. Low Cost Video For Distance Education. Doctoral dissertation. Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved from NSUWorks, Graduate School of Computer and Information Sciences. (842) https://nsuworks.nova.edu/gscis_etd/842. This Dissertation is brought to you by the College of Engineering and Computing at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in CEC Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Low Cost Video for Distance Education by Michael J. Simpson A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Computer and Information Sciences Nova Southeastern University 1996 We hereby certify that this dissertation, submitted by Michael J. Simpson, conforms to acceptable standards and is fully adequate in scope and quality to fulfill the dissertation requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________ Jacques C. Levin, Ph.D. Date Chairman of Dissertation Committee _______________________________________________________ John A. Scigliano, Ed.D. Date Dissertation Committee Member _______________________________________________________ Steven R. Terrell, Ed.D. -

Hardware Systems: Processor and Board Alternatives

Hardware Systems: Processor and Board Alternatives Afshin Attarzadeh INFOTECH, Universität Stuttgart, [email protected] Abstract: Nowadays parallel computing has a great influence in our daily life. Weather forecast, air control, modeling nuclear experiments instead of actually performing it and lots of other issues are directly related to parallel computing concept. Clusters in the issue of parallelism, are more commonly used today. The issue of clusters, like other concepts in parallelism, is a system issue which involves with software and hardware and their relation to each other. In this paper the hardware part is considered mostly. Introduction – What is cluster computing? As Pfister mentions in his book [1], there are three ways to improve performance: − Work harder − Work smarter − Get help To work harder is just like using faster hardware. This means using faster processors, faster and higher capacity of memory storage and peripheral devices with higher capabilities. Working smarter is when things are done more efficiently and this is due to use of efficient and faster algorithms and techniques. The last aspect deals with parallel processing. Clusters could be a good solution in utilizing all those three aspects of performance improvement with a reasonable expense! Clusters are so flexible that commodity components could be used in their hardware structure. Their flexibility allows designers in developing high performance parallel algorithms. Clusters could be easily configured and more over they are scalable. This means they can easily follow the technology advances in both hardware and software aspects. According to Buyya[2] the most common scalable parallel computer architectures could be classified as follows: • Massively Parallel Processors (MPP) • Symmetric Multiprocessors (SMP) • Cache-Coherent Nonuniform Memory Access (CC-NUMA) • Distributed Systems • Clusters 2 Afshin Attarzadeh Clusters – Definition and Architecture There are many different definitions on clusters. -

Oral History Panel on the Development and Promotion of the Intel 8008 Microprocessor

Oral History Panel on the Development and Promotion of the Intel 8008 Microprocessor Participants: Federico Faggin Hal Feeney Ed Gelbach Ted Hoff Stan Mazor Hank Smith Moderated by: Dave House Recorded: September 21, 2006 Mountain View, California CHM Reference number: X3706.2007 © 2006 Computer History Museum Oral History Panel on Intel 8008 Microprocessor Dave House: Stan, tell us how the 8008 began. Stan Mazor: Well, in today’s personal computers, we have RAM and we have flat panel displays, but in the middle of the ‘60s, we had core memories on our minicomputers and we typically used either a teletype or a CRT terminal (cathode ray tube). We also nicknamed these “glass teletypes” because they played the role of the teletype, but they were much faster. The key ingredient to the CRT terminal in those days was the shift register; there was no RAM memory in those days. Shift register were being provided by General Microelectronics, (GME), General Instrument and some other companies. When Intel got started in 1969 in the memory business, we were designing RAM components-- and we really had no customers for them. So one of the things that we did was---to do a custom order for Datapoint (formerly Computer Terminals Corporation) who was one of the makers of a cathode ray terminal, and we made for them a 512-bit re-circulating shift register. So this gave us a ready customer and it was a type of memory product which was in use at that time. Well, Datapoint, having been in the display [terminal] business, had an idea of going into the business terminal [computer] business; in addition and they had a clever idea, which was to use the shift registers that they were already using inside the display terminal as the main memory of their computer. -

The CPU and Memory

The defining component of any computer sys- tem is the central processing unit, or CPU. The design and architecture of the CPU deter- mine what instructions are available for pro- gramming it, how fast it will be able to run, and how data are organized and addressed. The CPU receives data and instructions from memory, performs arithmetic or logical opera- tions on the data, and returns the data to memory. The CPU can perform billions of such operations every second. Even though each op- eration is relatively simple, the CPU can per- form complex actions very quickly by Figure 3-1 combining those relatively simple operations. John von Neumann Los Alamos The first commercially available CPU, that of National Laboratory the UNIVAC I computer delivered to the Census Bureau in 1951,was about 14 feet long, about eight feet wide, and over eight feet tall. By 1970, the progress of Moore’s Law reduced the CPUs of some computers to a single circuit board. In 1971, Intel introduced the first CPU on a chip, intended for use in electronic calculators and incorporating about 2,250 transistors. Modern CPU chips have tens of billions of transistors. In the late 20th century, chips with multiple pro- cessing units were introduced. When a chip has more than one processing unit, the processing units are called cores. Also in the late 20th century, supporting circuitry like memory and bus control- lers began to be added to CPU chips. These evolved to become systems on a chip (SOCs). Today, CPU chips with external supporting circuitry are used where performance is the major factor, such as in servers and workstation com- puters. -

Datapoint: the Lost Story of the Texans Who Invented the Personal Computer Revolution by Lamont Wood Book

Datapoint: The Lost Story of the Texans Who Invented the Personal Computer Revolution by Lamont Wood book Ebook Datapoint: The Lost Story of the Texans Who Invented the Personal Computer Revolution currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Datapoint: The Lost Story of the Texans Who Invented the Personal Computer Revolution please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Paperback:::: 330 pages+++Publisher:::: Hugo House Publishers (August 30, 2012)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 1936449366+++ISBN-13:::: 978-1936449361+++Product Dimensions::::6.1 x 0.7 x 9.2 inches++++++ ISBN10 1936449366 ISBN13 978-1936449 Download here >> Description: Forget Apple and IBM. For that matter forget Silicon Valley. The first personal computer, a self-contained unit with its own programmable processor, display, keyboard, internal memory, telephone interface, and mass storage of data was born in San Antonio TX. US Patent number 224,415 was filed November 27, 1970 for a machine that is the direct lineal ancestor to the PC as we know it today. The story begins in 1968, when two Texans, Phil Ray and Gus Roche, founded a firm called Computer Terminal Corporation. As the name implies their first product was a Datapoint 3300 computer terminal replacement for a mechanical Teletype. However, they knew all the while that the 3300 was only a way to get started, and it was cover for what their real intentions were - to create a programmable mass-produced desktop computer. They brought in Jack Frassanito, Vic Poor, Jonathan Schmidt, Harry Pyle and a team of designers, engineers and programmers to create the Datapoint 2200. -

Genesis Article.Pdf

Genesis: A Silicon Valley Tale TECH HISTORY ARTICLE BY DR JEFF DROBMAN Highlights v Fairchild founding v Intel founding v AMD history v AMD – Intel rivalry v Search for CMOS v RISC CPU Architecture v Legendary Parties & Conferences v Anecdotes v Valley Significant Others v Genesis org-chart v Process Technology Evolution v Anniversaries of Technologies Preface [This article chronicles the founding and early history of this storied high-tech region of the San Francisco Peninsula – the halcyon days of chip Camelot. I have employed an AMD/Intel emphasis, since that rivalry is perhaps the most legendary and lasting, and all of their founders came from mother chip company Fairchild. This article represents my personal observations, opinions and later reflections – sprinkled with names, dates and facts. I apologize in advance for any inaccuracies, as most of it comes from my quite fallible memory. Moreover, I have a rather unique perspective, being both an outsider and an insider at the same time, starting in 1965. My sister married AMD founder WJ "Jerry" Sanders III when he was a sales manager with Fairchild. I was a junior engineering student at UCLA staying at their beach house in Malibu when plans for AMD were first being considered by the group of 8 from Fairchild. I actually did work for AMD during 1979-82, a period that would change AMD forever, due to the intro of the IBM PC.] The Legend It has long been legendary that companies in Silicon Valley got started in garages and beach houses, and I am setting the record straight: It is true. -

Poe, the Turk, and Babbage Oldest Working Computer Timothy Turtle

It was never a record- photograph, and decided to breaker for speed, with a rescue it from storage. multiplication taking April After restoration, the museum between 5 and 10 seconds. began running Dekatron demos in Cooke-Yarborough justified 2012, and the Guinness Book of Poe, the Turk, and its slow operation as a tradeoff for reliability – from World Records recognized the machine as the world’s oldest May 1952 until Feb. 1953, it Babbage working digital computer in 2013. averaged 80 hours of running April 1836 time per week. For the oldest working analog computer, see [Jan 00]. In 1769, Hungarian author and Cooke-Yarborough went on inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen to design its successor, the unveiled his chess-playing Harwell CADET [Feb 00], automaton, the Turk. Although the perhaps the first fully Timothy Turtle machine was seemingly filled with transistorized computer. an elaborate arrangement of gears, the cabinet also April 1953 concealed a man controlling the Turk's movements. “Timothy Turtle” was a robot created by Jack H Kubanoff One of the most insightful which responded to flashing commentators about the light via two photocells in its device was by Edgar Allan Poe head. It could ‘search’ for food, in the article, “Maelzel’s Chess ‘play’, and also return to its Player” in April 1836. He ‘nest’ to recharge. Its shell was argued that if the automaton shaped wire covered in paper was real then it must be able maché. to use the result of an operation to make a decision Timothy's schematics were about the next (i.e.