Operation Chariot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Introduction

Notes 1 Introduction 1. Donald Macintyre, Narvik (London: Evans, 1959), p. 15. 2. See Olav Riste, The Neutral Ally: Norway’s Relations with Belligerent Powers in the First World War (London: Allen and Unwin, 1965). 3. Reflections of the C-in-C Navy on the Outbreak of War, 3 September 1939, The Fuehrer Conferences on Naval Affairs, 1939–45 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1990), pp. 37–38. 4. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 10 October 1939, in ibid. p. 47. 5. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 8 December 1939, Minutes of a Conference with Herr Hauglin and Herr Quisling on 11 December 1939 and Report of the C-in-C Navy, 12 December 1939 in ibid. pp. 63–67. 6. MGFA, Nichols Bohemia, n 172/14, H. W. Schmidt to Admiral Bohemia, 31 January 1955 cited by Francois Kersaudy, Norway, 1940 (London: Arrow, 1990), p. 42. 7. See Andrew Lambert, ‘Seapower 1939–40: Churchill and the Strategic Origins of the Battle of the Atlantic, Journal of Strategic Studies, vol. 17, no. 1 (1994), pp. 86–108. 8. For the importance of Swedish iron ore see Thomas Munch-Petersen, The Strategy of Phoney War (Stockholm: Militärhistoriska Förlaget, 1981). 9. Churchill, The Second World War, I, p. 463. 10. See Richard Wiggan, Hunt the Altmark (London: Hale, 1982). 11. TMI, Tome XV, Déposition de l’amiral Raeder, 17 May 1946 cited by Kersaudy, p. 44. 12. Kersaudy, p. 81. 13. Johannes Andenæs, Olav Riste and Magne Skodvin, Norway and the Second World War (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1966), p. -

World War II at Sea This Page Intentionally Left Blank World War II at Sea

World War II at Sea This page intentionally left blank World War II at Sea AN ENCYCLOPEDIA Volume I: A–K Dr. Spencer C. Tucker Editor Dr. Paul G. Pierpaoli Jr. Associate Editor Dr. Eric W. Osborne Assistant Editor Vincent P. O’Hara Assistant Editor Copyright 2012 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data World War II at sea : an encyclopedia / Spencer C. Tucker. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-59884-457-3 (hardcopy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-59884-458-0 (ebook) 1. World War, 1939–1945—Naval operations— Encyclopedias. I. Tucker, Spencer, 1937– II. Title: World War Two at sea. D770.W66 2011 940.54'503—dc23 2011042142 ISBN: 978-1-59884-457-3 EISBN: 978-1-59884-458-0 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America To Malcolm “Kip” Muir Jr., scholar, gifted teacher, and friend. This page intentionally left blank Contents About the Editor ix Editorial Advisory Board xi List of Entries xiii Preface xxiii Overview xxv Entries A–Z 1 Chronology of Principal Events of World War II at Sea 823 Glossary of World War II Naval Terms 831 Bibliography 839 List of Editors and Contributors 865 Categorical Index 877 Index 889 vii This page intentionally left blank About the Editor Spencer C. -

United States Navy Carrier Air Group 12 History

CVG-12 USN Air 1207 October 1945 United States Navy Carrier Air Group 12 (CVG-12) Copy No. 2 History FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY This document is the property of the Government of the United States and is issued for the information of its Forces operating in the Pacific Theatre of Operations. 1 Original (Oct 45) PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com CVG-12 USN Air 1207 October 1945 Intentionally Blank 2 Original (Oct 45) PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com CVG-12 USN Air 1207 October 1945 CONTENTS CONTENTS........................................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................................3 USS Saratoga Embarkation..............................................................................................4 OPERATION SHOESTRING 2 ....................................................................................................4 THE RABAUL RAIDS .....................................................................................................................5 First Strike - 5 November 1943............................................................................................................5 Second Strike - 11 November 1943......................................................................................................7 OPERATION GALVIN....................................................................................................................7 -

Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress

Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress Updated October 29, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RS22478 Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress Summary Names for Navy ships traditionally have been chosen and announced by the Secretary of the Navy, under the direction of the President and in accordance with rules prescribed by Congress. Rules for giving certain types of names to certain types of Navy ships have evolved over time. There have been exceptions to the Navy’s ship-naming rules, particularly for the purpose of naming a ship for a person when the rule for that type of ship would have called for it to be named for something else. Some observers have perceived a breakdown in, or corruption of, the rules for naming Navy ships. Section 1749 of the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) (S. 1790/P.L. 116-92 of December 20, 2019) prohibits the Secretary of Defense, in naming a new ship (or other asset) or renaming an existing ship (or other asset), from giving the asset a name that refers to, or includes a term referring to, the Confederate States of America, including any name referring to a person who served or held leadership within the Confederacy, or a Confederate battlefield victory. The provision also states that “nothing in this section may be construed as requiring a Secretary concerned to initiate a review of previously named assets.” Section 1749 of the House-reported FY2021 NDAA (H.R. 6395) would prohibit the public display of the Confederate battle flag on Department of Defense (DOD) property, including naval vessels. -

Commandos at St. Nazaire

COMMANDOS AT ST. NAZAIRE Designed by Morgan GILLARD, with assistance from be tallied when counting victory points. Nicolas STRATIGOS The fuel depots, the three printed spaces #1, are [Translation by Roy Bartoo, includes errata, clarifications objectives which must be destroyed by demolition (11.1). & optional rules from a later issue of Vae Victis. But I Three markers objective #1 destroyed are included in didn’t bother to translate the historical article: find the VV73.] book “The Greatest Raid of All” and read it instead.] 1.2 Game Scale On March 28th, 1942, around one in the morning, a British The game lasts 10 turns and covers the period flotilla moved up the Loire estuary. Under intense fire between 1:30 a.m. and 4:00 a.m. A game turn equals 15 from German batteries, the destroyer HMS Campbeltown minutes of real time and 1 cm on the map equals 40 m of rammed the caisson closing the river side of the great real world distance. A unit counter represents a group of drydock of St. Nazaire, the only one along all the Atlantic about 5 to 17 men or a single vehicle, and a FlaK counter coast capable of taking the great German battleship Tirpitz. (German antiaircraft artillery) represents one gun and its Immediately groups of commandos debarked from it to crew. begin the systematic destruction of all the parts of the drydock. Simultaneously, light motor-torpedo boats tried 1.3 Play Aid to dock at the Old Mole and the Old Entrance in order to In addition to the map, a play aid is included, land their soldiers. -

The Evolution of the US Navy Into an Effective

The Evolution of the U.S. Navy into an Effective Night-Fighting Force During the Solomon Islands Campaign, 1942 - 1943 A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Jeff T. Reardon August 2008 © 2008 Jeff T. Reardon All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation titled The Evolution of the U.S. Navy into an Effective Night-Fighting Force During the Solomon Islands Campaign, 1942 - 1943 by JEFF T. REARDON has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Marvin E. Fletcher Professor of History Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences iii ABSTRACT REARDON, JEFF T., Ph.D., August 2008, History The Evolution of the U.S. Navy into an Effective Night-Fighting Force During the Solomon Islands Campaign, 1942-1943 (373 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Marvin E. Fletcher On the night of August 8-9, 1942, American naval forces supporting the amphibious landings at Guadalcanal and Tulagi Islands suffered a humiliating defeat in a nighttime clash against the Imperial Japanese Navy. This was, and remains today, the U.S. Navy’s worst defeat at sea. However, unlike America’s ground and air forces, which began inflicting disproportionate losses against their Japanese counterparts at the outset of the Solomon Islands campaign in August 1942, the navy was slow to achieve similar success. The reason the U.S. Navy took so long to achieve proficiency in ship-to-ship combat was due to the fact that it had not adequately prepared itself to fight at night. -

News and Views

World Ship Society Southend Branch News and Views Newsletter Edition 33 Edited 14th June 2021 Chairman & Secretary Stuart Emery [email protected] News & Views Coordinator Richard King [email protected] Notes Thanks go to Tony, Colin, Stuart, Phil and Eddie for their contributions Contents News Visitors Quiz Tony Type 31 Frigates Little Ships that keep our river going Part 2 PLA Colins pictures One fact Wonder Battle of Matapan Shipbuilding The Tyne – Vickers Armstrong -Walker -Part 2 Short History of a Line – MOL Quiz News Fjord1 orders two eco-friendly ferries from Tersan HAV DESIGN The ferries will operate on two routes in Norway Norwegian operator Fjord1 has ordered two eco-friendly car and passenger ferries from Turkey’s Tersan shipyard. Scheduled for delivery in the second quarter of 2023, the 248-person ferries have been designed by Norway-based firm HAV Design and will be able to accommodate 80 cars and six trailers. Both 84-metre-long vessels will have a battery-powered propulsion system, which can be charged via shore power while passengers are disembarking in port. They will also have a diesel-electric backup system to allow them to operate in either fully electric, hybrid or diesel-electric mode. Once in service, the vessels will operate on the routes between Stranda and Liabygda, and Eidsdal and Linge. Aurora Botnia successfully completes first sea trials RAUMA MARINE CONSTRUCTIONS Aurora Botnia pictured during her sea trials Wasaline’s new car and passenger ferry Aurora Botnia has successfully completed her first sea trials. The vessel, which is nearing completion at the Rauma Marine Constructions (RMC) shipyard in Finland, underwent three days of tests to assess operational performance. -

Operation Chariot Saint-Nazaire, 1942.3.28

15/09/2017 Operation Chariot Saint-Nazaire, 1942.3.28 « They achieved much having dared all » 1 15/09/2017 1. Historical background 2. Objectives of the raid 3. Geography and military constraints 4. Means applied/involved 5. The raid 6. The aftermath 7. Achievement 2 15/09/2017 the USA have joined the war in December 1941 Many convoys cross the Atlantic Ocean, carrying supply/goods from the USA to the UK 3 15/09/2017 But these convoys are easy targets for German U-Boote 4 15/09/2017 5 15/09/2017 6 15/09/2017 - UK navy ships more quickly destroyed than built, - UK in worrying military position, - UK at risk of loosing the war - Prime minister Churchill particularly concerned about Tirpitz battleship 7 15/09/2017 8 15/09/2017 « Normandie dock » • 350 m long • 50 m wide • 16,6 m high 9 15/09/2017 1. Historical background 2. Objectives of the raid 3. Geography and military constraints 4. Means applied/involved 5. The raid 6. The aftermath 7. Achievement 10 15/09/2017 11 15/09/2017 12 15/09/2017 1. Historical background 2. Objectives of the raid 3. Geography and military constraints 4. Means applied/involved 5. The raid 6. The aftermath 7. Achievement 13 15/09/2017 Return ticket to St Nazaire 14 15/09/2017 15 15/09/2017 1. Historical background 2. Objectives of the raid 3. Geography and military constraints 4. Means applied/involved 5. The raid 6. The aftermath 7. Achievement 16 15/09/2017 - More than 600 men (including very well trained commandos) and - destroyer HMS Campbeltown (I42), built at Bath Iron Works in 1919, 96m long , modified to look like a German warship and - 15 Motor Launches (MLs), 112-foot-long unarmored mahogany boats - 1 Motor Gunboat (MGB) carried a 2-pounder Vickers anti-aircraft gun, a couple of twin-mount .50-caliber machine guns and a semiautomatic 2-pounder gun. -

NEW JERSEY BUILT WARSHIPS at TOKYO BAY on 2 SEPTEMBER 1945 for the SIGNING of the INSTRUMENT of SURRENDER1 By: CAPTAIN LAWRENCE B

NJ WARSHIPS AT TOKYO BAY ON VJ Day ~ Capt. Lawrence B. Brennan, USN (Ret.) NEW JERSEY BUILT WARSHIPS AT TOKYO BAY ON 2 SEPTEMBER 1945 FOR THE SIGNING OF THE INSTRUMENT OF SURRENDER1 By: CAPTAIN LAWRENCE B. BRENNAN, U.S. NAVY (RETIRED)2 “from this solemn occasion a better world shall emerge out of the blood and carnage of the past, a world founded upon faith and understanding, a world dedicated to the dignity of man and the fulfillment of his most cherished wish for freedom, tolerance, and justice.” General of the Armies Douglas A. MacArthur, United States Army 2 September 1945 on board USS Missouri (BB 63) INTRODUCTION On 2 September 1945, 258 warships of the navies of victorious Allies anchored in Tokyo Bay, near the site where in 1853 Commodore Perry had anchored. The United States Navy, which undertook the bulk of the combat in the Pacific was the largest force; the Royal Navy and the Commonwealth Navies were well represented.3 This article is the story of more than 20 of the New Jersey-built major surface combatant U.S. Navy ships which were present on that historic morning. Fig. 1: Attendance certificate, Japanese surrender on the USS Missouri, signed by General of the Armies D. A. MacArthur, Fleet Admiral C. W. Nimitz, Admiral W. F. Halsey, and Captain S.S. Murray, September 2, 1945. 4 The combat commander of the Third Fleet which dominated the waters of Japan that day was a native of New Jersey, Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr. USN. The son of a naval officer, Halsey was born in Elizabeth in 1882 and educated at the Pingry School before attending the U.S. -

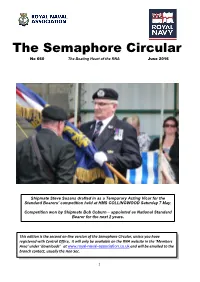

The Semaphore Circular No 660 the Beating Heart of the RNA June 2016

The Semaphore Circular No 660 The Beating Heart of the RNA June 2016 Shipmate Steve Susans drafted in as a Temporary Acting Vicar for the Standard Bearers’ competition held at HMS COLLINGWOOD Saturday 7 May. Competition won by Shipmate Bob Coburn – appointed as National Standard Bearer for the next 2 years. This edition is the second on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec. 1 Daily Orders 1. Remembrance Paraded 13 November 2016 2. National Standard Bearers Competition 3. Mini Cruise 4. Guess Where? 5. Donations 6. Teacher Joke 7. HMS Raleigh Open Day 8. RN VC Series – Capt Stephen Beattie 9. Finance Corner 10. St Lukes Hospital Haslar 11. Trust your Husband Joke 12. Assistance please – Ludlow Ensign 13. Further Assistance please Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Crossed the Bar – Celebrating a life well lived RNA Benefits Page Shortcast Swinging the Lamp Forms Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General Secretary DGS Deputy General Secretary AGS Assistant General Secretary CONA Conference of Naval Associations IMC International Maritime Confederation NSM Naval Service Memorial Throughout indicates -

The St Nazaire Raid What’S Included

World War Two Tours Operation Chariot: The St Nazaire Raid What’s included: Hotel Bed & Breakfast All transport from the official overseas start point Accompanied for the trip duration All Museum entrances All Expert Talks & Guidance Low Group Numbers “Thank you for a great visit. Steve and I really enjoyed it. We’ll be happy to recommend your trips there – you certainly know your stuff and I’m very The St Nazaire Raid, or Operation Chariot, was a successful British amphibious attack on the glad we found you.” heavily defended Normandie dry dock at St Nazaire in German-occupied France during the Second World War. The operation was undertaken by the Royal Navy and British Commandos under the auspices of Combined Operations Headquarters on 28 March 1942. St Nazaire was targeted because the loss of its dry dock would force any large German warship in need of Military History Tours is all about the ‘experience’. Naturally we take repairs, such as the Tirpitz, to return to home waters rather than having a safe haven available care of all local accommodation, transport and entrances but what on the Atlantic coast. sets us aside is our on the ground knowledge and contacts, established The obsolete destroyer HMS Campbeltown, accompanied by 18 smaller craft, crossed the English over many, many years that enable you to really get under the surface of Channel to the Atlantic coast of France and was rammed into the Normandie dock gates. The your chosen subject matter. ship had been packed with delayed-action explosives, well hidden within a steel and concrete By guiding guests around these case, that detonated later that day, putting the dock out of service for the remainder of the historic locations we feel we are contributing greatly towards ‘keeping war and up to ten years after. -

1. Port. Cont. MAYO 10 27/5/10 13:31 Página 2 3 Y 4

1. Port. Cont. MAYO 10 27/5/10 13:31 Página 1 año LXXIX • n° 881 mayo 2010 INGENIERIA NAVAL mayo 2010 Revista del sector Marítimo n° 881 INGENIERIA NAVAL industria auxiliar 1. Port. Cont. MAYO 10 27/5/10 13:31 Página 2 3 y 4. Anuncios 27/5/10 16:37 Página 3 3 y 4. Anuncios 27/5/10 16:37 Página 4 5. Sumario MAYO 10 27/5/10 16:37 Página 5 año LXXIX • n.° 881 INGENIERIA NAVAL mayo 2010 6 website / website 67 I+D+i / R & D & i 7 editorial / editorial comment 69 nuestras instituciones / our institutions 9 sector maritimo. coyuntura / shipping and 75 nuestros mayores / our elders shipbuilding news 77 congresos / congresses 21 industria auxiliar / auxiliary industry 81 publicaciones / publications 27 gobierno y maniobra / steering and hace 50 años / 50 years ago manoevuvre 83 85 artículo técnico / technical articles 29 construcción naval / shipbuilding • Situación y perspectiva de mercado de astilleros • Buque ferry Abel Matutes offshore, por A. Méndez Díaz y F. de Bartolomé • Entrega del remolcador Tomasso Onorato Guijosa • AHTS Loke Viking construido por Zamakona 94 agenda / agenda 55 noticias / news 96 clasificados / directory Consejo Técnico Asesor D. Francisco Bartolomé Guijosa D. Manuel Carlier De Lavalle 39 D. Diego Colón de Carvajal Gorosabel AHTS Loke Viking D. José María de Juan-García Aguado D. Francisco Fernández González construido por Zamakona. D. Luis Francisco García De España Descripción de las D. Víctor González Sánchez características principales D. Rafael Gutiérrez Fraile en español y en inglés D. José Antonio Lagares D. Montes Martín Agustín D.