Whaling Shipwrecks in the Northwest Hawaiian Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan—Pacific Region

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan Conservation Seabird Pacific Region U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan—Pacific Region 120 0’0"E 140 0’0"E 160 0’0"E 180 0’0" 160 0’0"W 140 0’0"W 120 0’0"W 100 0’0"W RUSSIA CANADA 0’0"N 0’0"N 50 50 WA CHINA US Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Region OR ID AN NV JAP CA H A 0’0"N I W 0’0"N 30 S A 30 N L I ort I Main Hawaiian Islands Commonwealth of the hwe A stern A (see inset below) Northern Mariana Islands Haw N aiian Isla D N nds S P a c i f i c Wake Atoll S ND ANA O c e a n LA RI IS Johnston Atoll MA Guam L I 0’0"N 0’0"N N 10 10 Kingman Reef E Palmyra Atoll I S 160 0’0"W 158 0’0"W 156 0’0"W L Howland Island Equator A M a i n H a w a i i a n I s l a n d s Baker Island Jarvis N P H O E N I X D IN D Island Kauai S 0’0"N ONE 0’0"N I S L A N D S 22 SI 22 A PAPUA NEW Niihau Oahu GUINEA Molokai Maui 0’0"S Lanai 0’0"S 10 AMERICAN P a c i f i c 10 Kahoolawe SAMOA O c e a n Hawaii 0’0"N 0’0"N 20 FIJI 20 AUSTRALIA 0 200 Miles 0 2,000 ES - OTS/FR Miles September 2003 160 0’0"W 158 0’0"W 156 0’0"W (800) 244-WILD http://www.fws.gov Information U.S. -

NEW to SHIP MODELING? Become a Shipwright of Old

NEW TO SHIP MODELING? Become a Shipwright of Old These Model Shipways Wood Kits designed by master modeler David Antscherl, will teach you the skills needed to build mu- seum quality models. See our kit details online. Lowell Grand Banks Dory A great introduction to model ship building. This is the first boat in a series of progressive 1:24 Scale Wood Model Model Specifications: model tutorials! The combo tool kit comes com- Length: 10” , Width 3” , Height 1-1/2” • plete with the following. Hobby Knife & Multi Historically accurate, detailed wood model • Blades, Paint & Glue, Paint Brushes, Sand- Laser cut basswood parts for easy construction • paper, Tweezers, & Clamps. Dories were de- Detailed illustrated instruction manual • True plank-on-frame construction • veloped on the East Coast in the 1800’s. They Wooden display base included • were mainly used for fishing and lobstering. Skill Level 1 MS1470CB - Wood Model Dory Combo Kit - Paint & Tools: $49.99 MS1470 - Wood Model Dory Kit Only: $29.99 Norwegian Sailing Pram Muscongus Bay Lobster Smack 1:24 Scale Wood Model 1:24 Scale Wood Model Model Specifications: Model Specifications: Length 12½”, Width 4”, Height 15½ • Length 14½”, Width 3¾”, Height 14” • Historically accurate, detailed wood model • Historically accurate, detailed wood model • Laser cut basswood parts for easy construction • Laser cut basswood parts for easy construction • Detailed illustrated instruction manual • Detailed illustrated instruction manual • True plank-on-frame construction • True plank-on-frame construction • Wooden display base included • Wooden display base included • Skill Level 2 Skill Level 3 This is the second intermediate kit This is the third and last kit in this for this series of progressive model series of progressive model tutori- tutorials. -

A New Bedford Voyage!

Funding in Part by: ECHO - Education through Cultural and Historical Organizations The Jessie B. DuPont Fund A New Bedford Voyage! 18 Johnny Cake Hill Education Department New Bedford 508 997-0046, ext. 123 Massachusetts 02740-6398 fax 508 997-0018 new bedford whaling museum education department www.whalingmuseum.org To the teacher: This booklet is designed to take you and your students on a voyage back to a time when people thought whaling was a necessity and when the whaling port of New Bedford was known worldwide. I: Introduction page 3 How were whale products used? What were the advantages of whale oil? How did whaling get started in America? A view of the port of New Bedford II: Preparing for the Voyage page 7 How was the whaling voyage organized? Important papers III: You’re on Your Way page 10 Meet the crew Where’s your space? Captain’s rules A day at sea A 24-hour schedule Time off Food for thought from the galley of a whaleship How do you catch a whale? Letters home Your voice and vision Where in the world? IV: The End of the Voyage page 28 How much did you earn? Modern whaling and conservation issues V: Whaling Terms page 30 VI: Learning More page 32 NEW BEDFORD WHALING MUSEUM Editor ECHO Special Projects Illustrations - Patricia Altschuller - Judy Chatfield - Gordon Grant Research Copy Editor Graphic Designer - Stuart Frank, Michael Dyer, - Clara Stites - John Cox - MediumStudio Laura Pereira, William Wyatt Special thanks to Katherine Gaudet and Viola Taylor, teachers at Friends Academy, North Dartmouth, MA, and to Judy Giusti, teacher at New Bedford Public Schools, for their contributions to this publication. -

Modern Whaling

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: In Pursuit of Leviathan: Technology, Institutions, Productivity, and Profits in American Whaling, 1816-1906 Volume Author/Editor: Lance E. Davis, Robert E. Gallman, and Karin Gleiter Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-13789-9 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/davi97-1 Publication Date: January 1997 Chapter Title: Modern Whaling Chapter Author: Lance E. Davis, Robert E. Gallman, Karin Gleiter Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8288 Chapter pages in book: (p. 498 - 512) 13 Modern Whaling The last three decades of the nineteenth century were a period of decline for American whaling.' The market for oil was weak because of the advance of petroleum production, and only the demand for bone kept right whalers and bowhead whalers afloat. It was against this background that the Norwegian whaling industry emerged and grew to formidable size. Oddly enough, the Norwegians were not after bone-the whales they hunted, although baleens, yielded bone of very poor quality. They were after oil, and oil of an inferior sort. How was it that the Norwegians could prosper, selling inferior oil in a declining market? The answer is that their costs were exceedingly low. The whales they hunted existed in profusion along the northern (Finnmark) coast of Norway and could be caught with a relatively modest commitment of man and vessel time. The area from which the hunters came was poor. Labor was cheap; it also happened to be experienced in maritime pursuits, particularly in the sealing industry and in hunting small whales-the bottlenose whale and the white whale (narwhal). -

Sharing the Catches of Whales in the Southern Hemisphere

SHARING THE CATCHES OF WHALES IN THE SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE S.J. Holt 4 Upper House Farm,Crickhowell, NP8 1BZ, Wales (UK) <[email protected]> 1. INTRODUCTION What historians have labelled modern whaling is largely a twentieth century enterprise. Its defining feature is the cannon-fired harpoon with an explosive head, launched from a motorised catcher boat.1 This system was first devised about 1865 by Svend Foyn, the son of a ship-owner from Tønsberg, in Vestfold, southeast Norway. Foyn believed that “God had let the whale inhabit the waters for the benefit and blessing of mankind, and consequently I considered it my vocation to promote these fisheries”. He has been described as “...a man with great singularity of vision, since virtually everything he did ...was dedicated to the profitable killing of whales”. Foyn’s system allowed for the first time the systematic hunting and killing of the largest and fastest swimming species of whales, the rorquals, a sub-class of whalebone whales (Mysticetes spp.). The basic technology was supplemented by significant developments in cabling, winches and related hardware and in processing. Powered vessels could not only tow the dead rorquals back to land bases quickly and thus in good condition for processing, but could provide ample compressed air to keep them afloat. Modern whaling could not, however, have become a major industry world-wide, without other technological developments. Other kinds of whales had already been killed in enormous numbers, primarily for their oil, for over a century.2 In 1905 it was discovered that oil from baleen whales could be hydrogenated and the resulting product could be used in the manufacture of soap and food products. -

Clipper Ships ~4A1'11l ~ C(Ji? ~·4 ~

2 Clipper Ships ~4A1'11l ~ C(Ji? ~·4 ~/. MODEL SHIPWAYS Marine Model Co. YOUNG AMERICA #1079 SEA WITCH Marine Model Co. Extreme Clipper Ship (Clipper Ship) New York, 1853 #1 084 SWORDFISH First of the famous Clippers, built in (Medium Clipper Ship) LENGTH 21"-HEIGHT 13\4" 1846, she had an exciting career and OUR MODEL DEPARTMENT • • • Designed and built in 1851, her rec SCALE f."= I Ft. holds a unique place in the history Stocked from keel to topmast with ship model kits. Hulls of sailing vessels. ord passage from New York to San of finest carved wood, of plastic, of moulded wood. Plans and instructions -··········-·············· $ 1.00 Francisco in 91 days was eclipsed Scale 1/8" = I ft. Models for youthful builders as well as experienced mplete kit --·----- $10o25 only once. She also engaged in professionals. Length & height 36" x 24 " Mahogany hull optional. Plan only, $4.QO China Sea trade and made many Price complete as illustrated with mahogany Come a:r:1d see us if you can - or send your orders and passages to Canton. be assured of our genuine personal interest in your Add $1.00 to above price. hull and baseboard . Brass pedestals . $49,95 selection. Scale 3/32" = I ft. Hull only, on 3"t" scale, $11.50 Length & height 23" x 15" ~LISS Plan only, $1.50 & CO., INC. Price complete as illustrated with mahogany hull and baseboard. Brass pedestals. POSTAL INSTRUCTIONS $27.95 7. Returns for exchange or refund must be made within 1. Add :Jrt postage to all orders under $1 .00 for Boston 10 days. -

Talley's New Zealand Skipjack Tuna Purse Seine

Acoura Marine Final Report Talley's New Zealand skipjack tuna purse seine MSC SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES CERTIFICATION Talley's New Zealand Skipjack Tuna Purse Seine Final Report February 2017 Prepared For: Talley’s Group Limited Prepared By: Acoura Marine Ltd Authors: Jo Akroyd & Kevin McLoughlin Acoura Marine Full Assessment Template per MSC V2.0 02/12/2015 Acoura Marine Final Report Talley's New Zealand skipjack tuna purse seine Contents Glossary................................................................................................................................ 4 1 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 6 2 Authorship and Peer Reviewers ..................................................................................... 8 2.1 Assessment Team .................................................................................................. 8 2.1.1 Peer Reviewers .................................................................................................... 9 2.1.2 RBF Training ........................................................................................................ 9 3 Description of the Fishery ............................................................................................ 10 3.1 Unit(s) of Assessment (UoA) and scope of certification sought .................................. 10 3.1.1 The proposed Unit of Assessment for this fishery is as below: ............................ 10 3.1.2 The proposed unit of Certification -

La Marina Maltese Dal Medio Evo All'epoca Moderna Storia E

LA MARINA MALTESE DAL MEDIO EVO ALL'EPOCA MODERNA STORIA E TERMINOLOGIA MARITTIMA Di A. CREMONA MAI.:rA posta a. meta del tramite marittimo del Mediterraneo fra la costa europea e quella dell' Africa Settentrionale ba fin dai tempi non ricordati dalla storia offeno ai navigatori il punto piu ospitale e favorevole di sosta e ricovero nel traffico marittimo dall'oriente verso le terre del mezzogiomo e perfino fuori dallo stretto di Gibilterra verso le terre nordicbe. Cio 10 dimostrano le tracce di tempt e' dimore megalicicbe cbe si attti buiscono ai primi colonizzatori dell'isola nei pressi della costa in diversi punci eminenti e piu intensamente le tombe punicbe nella parte occidentale dell'i sola. Ai Fenici e Cartaginesi cbe abitarono l'isola nei primordi del periodo storico si riconosce la nascita di una intensa navigazione Del bacino mediterraneo con it loro deposito commerdale nell'isole di Malta. Fin dal secolo IX i Fenici avevano fondato colonie nell'occidente della Sid lia prima dei Greci cbe rivaleggiarono con i Fenici nell'attivita commer ciale. Utica, presso Cartagine, sarebbe la piu antica colonia fenicia, poi Tiro e la nuova citta di Cartagine. I Fenici occuparono ancbe il mezzo giomo della Spagna; si comprende percio come la posizione invidiabile delle isole di Malta, con i loro seni di mare, era piu cbe un invito al traffi co commerciale dei navigatori fenici nella loro concorrenza con la Grecia. Si deve presumere cbe il commercio marittimo tra le terre italicbe e la costa dell' Africa settenttionale ebbe il primo sviluppo durante il periado romano quando le terre dell a costa africana settentrionale dalla Cirenaica fino ai confini della Libia erano l' emporio delle terre europee adiacenti al mare mediterraneo. -

The Eastern Shore in Robert De Gast's Wake Kristen L. Greenaway

The Eastern Shore in Robert de Gast’s Wake Kristen L. Greenaway Faculty Advisor: Kent Wicker Graduate Liberal Studies February 28, 2017 This project was submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Liberal Studies Program in the Graduate School of Duke University. Copyright by Kristen L. Greenaway 2017 Abstract When any space becomes familiar, it becomes a place. Thus, place is a uniquely personal concept. This project began with a passion to explore this place I now call home—the Eastern Shore—and find a way to best define that sense of place. Evoked by one specific text, Western Wind Eastern Shore: A Sailing Cruise around the Eastern Shore of Maryland, Delaware, and Virginia (1975), written and photographed by Robert de Gast, I discovered the means to achieve both goals: follow in his wake, by circumnavigating the Eastern Shore by boat; and to capture that experience via writing a personal essay, including photographs, of the places we visited—just as de Gast did. Through this process, I discover that sense of place cannot be easily defined except through being conscious of one’s experiences as one inhabits or moves through a range of natural, built and social environments. Putting myself on a boat, with particular companions, on a planned route, provided me with a range of such experiences, a narrative for making sense of them, and the focus necessary for that consciousness. In performing my own engagement with place, I found I was able to create my own personal definition of place in relation to the Eastern Shore. -

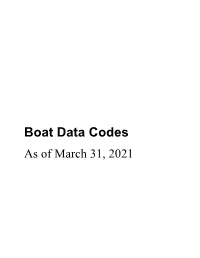

Boat Data Codes As of March 31, 2021 Boat Data Codes Table of Contents

Boat Data Codes As of March 31, 2021 Boat Data Codes Table of Contents 1 Outer Boat Hull Material (HUL) Field Codes 2 Propulsion (PRO) Field Codes 3 Canadian Vehicle Index Propulsion (PRO) Field Codes 4 Boat Make Field Codes 4.1 Boat Make and Boat Brand (BMA) Introduction 4.2 Boat Make (BMA) Field Codes 4.3 Boat Parts Brand Name (BRA) Field Codes 5 Boat Type (BTY) Field Codes 6 Canadian Boat Type (TYP) Field Codes 7 Boat Color (BCO) Field Codes 8 Boat Hull Shape (HSP) Field Codes 9 Boat Category Part (CAT) Field Codes 10 Boat Engine Power or Displacement (EPD) Field Codes 1 - Outer Boat Hull Material (HUL) Field Codes The code from the list below that best describes the material of which the boat's outer hull is made should be entered in the HUL Field. Code Material 0T OTHER ML METAL (ALUMINUM,STEEL,ETC) PL PLASTIC (FIBERGLASS UNIGLAS,ETC.) WD WOOD (CEDAR,PLYWOOD,FIR,ETC.) March 31, 2021 2 2 - Propulsion (PRO) Field Codes INBOARD: Any boat with mechanical propulsion (engine or motor) mounted inside the boat as a permanent installation. OUTBOARD: Any boat with mechanical propulsion (engine or motor) NOT located within the hull as a permanent installation. Generally the engine or motor is mounted on the transom at the rear of the boat and is considered portable. Code Type of Propulsion 0B OUTBOARD IN INBOARD MP MANUAL (OARS PADDLES) S0 SAIL W/AUXILIARY OUTBOARD POWER SA SAIL ONLY SI SAIL W/AUXILIARY INBOARD POWER March 31, 2021 3 3 - Canadian Vehicle Index Propulsion (PRO) Field Codes The following list contains Canadian PRO Field codes that are for reference only. -

Tahoe Boat Inspections the Boat Book

Tahoe Boat Inspections Watercraft Reference Book The Boat Book Wednesday, April 19, 2017 Table of Contents Chapter 1: What is a Boat Page 1 Chapter 2: Types of Watercraft Page 3 Ski Boats Page 3 Wakeboard Boats Page 5 Off-Shore Racers Page 7 Pleasure Boats Page 9 Fishing Boats Page 13 Sail Boats Page 16 Wooden Boats Page 18 Personal Watercraft (PWC) Page 20 Chapter 3: Types of Marine Engines Page 23 Carbureted Two-Stroke Page 23 Electronic Fuel Injected 2 Strokes Page 24 Two-Stroke Direct Fuel Injected (DFI) Page 25 Carbureted Four-Stroke Page 26 Electronic Fuel Injected (EFI) Four Stroke Page 27 Chapter 4: Cooling Systems Page 28 Open Loop Page 28 Decontaminating Open Loop Cooling Systems Page 29 Closed Loop Page 30 Decontaminating Closed Loop Cooling Systems Page 30/31 Air Cooling Page 32 Sea Pumps and Impellers Page 33 Chapter 5: Drives and Propulsion Page 34 Stern Drives Page 34 Decontaminating a Stern Drive Page 35 V Drives Page 37 Direct Drives Page 38 Decontaminating a V Drive or Direct Drive Page 38 Outboards Page 41 Electric Page 42 Jet Page 42 Decontaminating an Outboard Page 42 Jet Drives Page 45 Decontaminating a Jet Drive (PWC’s) Page 46 Decontaminating a Jet Drive (Boats) Page 52 Wednesday, April 19, 2017 Chapter 6: Optional Raw Water Systems Page 55 Ballast Systems Page 56 Single Intake Page 56 Multiple Intakes Page 56 Gravity Fill Page 56 Removable Systems Page 57 Sea Cock Page 58 Sea Strainer Page 58 Check Valve Page 58 Vented Loop Page 58 Manifold Page 58 Solenoid Valves Page 59 Aerator Pump Page 59 Reversible Pump Page -

Record Unit 207 Whaling and the Vineyard, 1793-1925 by Nancy Young

- 1 - Finding Aid to the Martha’s Vineyard Museum Record Unit 207 Whaling and the Vineyard, 1793-1925 By Nancy Young Descriptive Summary: Repository: Martha‟s Vineyard Museum Call No. Title: Whaling and the Vineyard, 1793-1925 Quantity: 5.25 cubic feet of material. Abstract: This collection documents the social and economic importance of the whaling industry to Martha‟s Vineyard. The collection spans the Atlantic whaling of the pre-Revolution era to the Pacific whaling of the 19th century to the later Arctic whaling. Administrative Information Acquisition Information: The Whaling and the Vineyard Collection was acquired by the Martha‟s Vineyard Museum during the 20th century; many donors contributed to the growth of this compilation. Processing Information: Nancy Young Access Restrictions: none Use Restrictions: none Preferred citation for publication: Martha‟s Vineyard Museum, Whaling and the Vineyard, 1793-1925, Record Unit 207. Index Terms Series and Subseries Arrangement Series I. Personal Correspondence Subseries A: Letters from Crew, 1794-1870 Subseries B: Letters to Crew, 1875-1897 Subseries C: Captain‟s Correspondence, 1823-1888 Series II: Business Correspondence Subseries A. Letters from Captain, 1817-1865 Subseries B. Letters to Captain, 1793- 1888 Subseries C. Owner/ Shareholder Correspondence, 1832- 1877 Series III: Business Records Subseries A: Accounts Subseries B: Receipts Subseries C: Official Papers Series IV: Logbooks Whaling and the Vineyard Series V: Memoirs Series VI: Social World of a Whaling Vessel Subseries A: