Hebrews Cambridge University Press C, F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa was consecrated as the Roman Catholic Diocesan Bishop of Botucatu in Brazil on December !" #$%&" until certain views he expressed about the treatment of the Brazil’s poor, by both the civil (overnment and the Roman Catholic Church in Brazil caused his removal from the Diocese of Botucatu. His Excellency was subsequently named as punishment as *itular bishop of Maurensi by the late Pope Pius +, of the Roman Catholic Church in #$-.. His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord Carlos Duarte Costa had been a strong advocate in the #$-0s for the reform of the Roman Catholic Church" he challenged many of the 1ey issues such as • Divorce" • challenged mandatory celibacy for the clergy, and publicly stated his contempt re(arding. 2*his is not a theological point" but a disciplinary one 3 Even at this moment in time in an interview with 4ermany's Die 6eit magazine the current Bishop of Rome" Pope Francis is considering allowing married priests as was in the old time including lets not forget married bishops and we could quote many Bishops" Cardinals and Popes over the centurys prior to 8atican ,, who was married. • abuses of papal power, including the concept of Papal ,nfallibility, which the bishop considered a mis(uided and false dogma. His Excellency President 4et9lio Dornelles 8argas as1ed the Holy :ee of Rome for the removal of His Excellency Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa from the Diocese of Botucatu. *he 8atican could not do this directly. 1 | P a g e *herefore the Apostolic Nuncio to Brazil entered into an agreement with the :ecretary of the Diocese of Botucatu to obtain the resi(nation of His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord. -

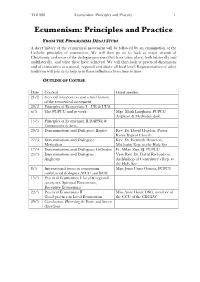

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC JOURNEY OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI TO BRAZIL ON THE OCCASION OF THE FIFTH GENERAL CONFERENCE OF THE BISHOPS OF LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN MEETING AND CELEBRATION OF VESPERS WITH THE BISHOPS OF BRAZIL ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI Catedral da Sé, São Paulo Friday, 11 May 2007 Dear Brother Bishops! "Although he was the Son of God, he learned obedience through what he suffered; and being made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation to all who obey him." (cf. Heb 5:8-9). 1. The text we have just heard in the Lesson for Vespers contains a profound teaching. Once again we realize that God’s word is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword; it penetrates to the depths of the soul and it grants solace and inspiration to his faithful servants (cf. Heb 4:12). I thank God for the opportunity to be with this distinguished Episcopate, which presides over one of the largest Catholic populations in the world. I greet you with a sense of deep communion and sincere affection, well aware of your devotion to the communities entrusted to your care. The warm reception given to me by the Rector of the Catedral da Sé and by all present has made me feel at home in this great common House which is our Holy Mother, the Catholic Church. 2 I extend a special greeting to the new Officers of the National Conference of Brazilian Bishops and, with gratitude for the kind words of its President, Archbishop Geraldo Lyrio Rocha, I offer prayerful good wishes for his work in deepening communion among the Bishops and in promoting common pastoral activity in a territory of continental dimensions. -

Solidarity and Mediation in the French Stream Of

SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Timothy R. Gabrielli Dayton, Ohio December 2014 SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. APPROVED BY: _________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Anthony J. Godzieba, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Timothy R. Gabrielli All rights reserved 2014 iii ABSTRACT SOLIDARITY MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. In its analysis of mystical body of Christ theology in the twentieth century, this dissertation identifies three major streams of mystical body theology operative in the early part of the century: the Roman, the German-Romantic, and the French-Social- Liturgical. Delineating these three streams of mystical body theology sheds light on the diversity of scholarly positions concerning the heritage of mystical body theology, on its mid twentieth-century recession, as well as on Pope Pius XII’s 1943 encyclical, Mystici Corporis Christi, which enshrined “mystical body of Christ” in Catholic magisterial teaching. Further, it links the work of Virgil Michel and Louis-Marie Chauvet, two scholars remote from each other on several fronts, in the long, winding French stream. -

The 18Th International Congress of Jesuit Ecumenists”

“The 18th International Congress of Jesuit Ecumenists” ................................................................. 2 “Conversion to Interreligious Dialogue.....”, James T. Bretzke, S.J. ................................................. 2 “The Practice of Daoist (Taoist) Compassion”, Michael Saso, S.J. .................................................. 3 “Kehilla, Church and Jewish people”, David Neuhaus, S.J. ............................................................. 6 “Let us Cross Over the Other Shore”, Christophe Ravanel, S.J. ………………………………….….10 “Six Theses on Islam in Europe”, Groupe des Deux Rives……………………………………….11 “Meeting of Jesuits in Islamic Studies, September 2006” .............................................................. 13 “Encounter and the Risk of Change”, Wilfried Dettling, S.J. ......................................................... 14 Secretariat for Interreligious Dialogue; Curia S.J., C.P. 6139, 00195 Roma Prati, Italy; N.11 tel. (39) 06.689.77.567/8; fax: 06.689.77.580; e-mail: [email protected] 2006 4 Vatican II, through the conceptual revolution THE 18TH INTERNATIONAL in ecumenical appreciation produced by CONGRESS OF Unitatis Redintegratio, and into the more JESUIT ECUMENISTS recent involvement of Jesuits in the ecumenical movement since the time of the Second Vatican Council. Edward Farrugia The Jesuit Ecumenists are an informal group looks at a specific issue that lies at the heart of Jesuit scholars active in the movement for of Catholic-Orthodox relations, that of the Christian unity who have -

The Concept of “Sister Churches” in Catholic-Orthodox Relations Since

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA The Concept of “Sister Churches” In Catholic-Orthodox Relations since Vatican II A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Will T. Cohen Washington, D.C. 2010 The Concept of “Sister Churches” In Catholic-Orthodox Relations since Vatican II Will T. Cohen, Ph.D. Director: Paul McPartlan, D.Phil. Closely associated with Catholic-Orthodox rapprochement in the latter half of the 20 th century was the emergence of the expression “sister churches” used in various ways across the confessional division. Patriarch Athenagoras first employed it in this context in a letter in 1962 to Cardinal Bea of the Vatican Secretariat for the Promotion of Christian Unity, and soon it had become standard currency in the bilateral dialogue. Yet today the expression is rarely invoked by Catholic or Orthodox officials in their ecclesial communications. As the Polish Catholic theologian Waclaw Hryniewicz was led to say in 2002, “This term…has now fallen into disgrace.” This dissertation traces the rise and fall of the expression “sister churches” in modern Catholic-Orthodox relations and argues for its rehabilitation as a means by which both Catholic West and Orthodox East may avoid certain ecclesiological imbalances toward which each respectively tends in its separation from the other. Catholics who oppose saying that the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church are sisters, or that the church of Rome is one among several patriarchal sister churches, generally fear that if either of those things were true, the unicity of the Church would be compromised and the Roman primacy rendered ineffective. -

Joseph Ratzinger, Student of Thomas

Berkeley Journal of Religion and Theology Volume 5, Issue 1 ISSN 2380-7458 Joseph Ratzinger, Student of Thomas Author(s): Jose Isidro Belleza Source: Berkeley Journal of Religion and Theology 5, no. 1 (2019): 94-120. Published by: Graduate Theological Union © 2019 Online article published on: August 20, 2019 Copyright Notice: This file and its contents is copyright of the Graduate Theological Union © 2019. All rights reserved. Your use of the Archives of the Berkeley Journal of Religion and Theology (BJRT) indicates your acceptance of the BJRT’s policy regarding the use of its resources, as discussed below: Any redistribution or reproduction of part or all of the contents in any form is prohibited with the following exceptions: Ø You may download and print to a local hard disk this entire article for your personal and non- commercial use only. Ø You may quote short sections of this article in other publications with the proper citations and attributions. Ø Permission has been obtained from the Journal’s management for exceptions to redistribution or reproduction. A written and signed letter from the Journal must be secured expressing this permission. To obtain permissions for exceptions, or to contact the Journal regarding any questions regarding any further use of this article, please e-mail the managing editor at [email protected] The Berkeley Journal of Religion and Theology aims to offer its scholarly contributions free to the community in furtherance of the Graduate Theological Union’s mission. Joseph Ratzinger, Student of Thomas Jose Isidro Belleza Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology Berkeley, California, U.S.A. -

Recent Roman Catholic Theology with Special Reference to Vatican II

Durham E-Theses The church and the unbeliever: recent Roman Catholic theology with special reference to Vatican II Greenwood, Robin P. How to cite: Greenwood, Robin P. (1971) The church and the unbeliever: recent Roman Catholic theology with special reference to Vatican II, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10103/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 THE CHURCH AND THE UNBELIEVER THE CHURCH AND THE UNBELIEVER Recent Roman Catholic Theology vdth special reference to Vatican II. A Thesis in canditature for the Degree of Master of Arts in the University of Durham presented by The Reverend Robin P. Greenwood, B.A. Dip.Th., (Dunelm) Ascension Day, S. Chad's College, Durham. 1971. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

Catholic Church’ Subsists in the ‘Catholic Church’

Theological Trends THE ‘CATHOLIC CHURCH’ SUBSISTS IN THE ‘CATHOLIC CHURCH’ Peter Knauer HE EIGHTH PARAGRAPH OF Vatican II’s Constitution on the T Church, Lumen gentium, speaks of the Church founded by Christ: This is the one Church of Christ which in the Creed is professed as one, holy, catholic and apostolic, which our Saviour, after His Resurrection, commissioned Peter to shepherd (John 21:17), and him and the other apostles to extend and direct with authority (see Matthew 28:18-19), which He erected for all ages as ‘the pillar and mainstay of the truth’ (1 Timothy 3:15). This Church, constituted and organized in the world as a society, subsists in the Catholic Church, which is governed by the successor of Peter and by the Bishops in communion with him, although many elements of sanctification and of truth are found outside of its visible structure. These elements, as gifts belonging to the Church of Christ, are forces impelling toward catholic unity. If you read this text as a whole, putting together the beginning of the first sentence with the beginning of the second, it seems to be saying something very odd indeed: the ‘Catholic Church’ referred to in the Creed subsists in the ‘Catholic Church’.1 It can only be making sense if ‘Catholic Church’ is being used in two different senses. What, then, does ‘Catholic Church’ mean in each case? And which version is intended when Unitatis redintegratio, the Council’s decree on ecumenism, speaks about people other than Catholics, and says that ‘it is only through Christ’s Catholic Church, which is “the all-embracing 1 It is worth noting that this formulation was taken over verbatim into the Code of Canon Law (204.2). -

Nature and Purpose of Ecumenical Dialogue

Cardinal Walter Kasper 1DWXUHDQG3XUSRVHRI(FXPHQLFDO'LDORJXH E\&DUGLQDO:DOWHU.DVSHU ,$%XUQLQJ4XHVWLRQ The 20th century, which started with a strong impulse of faith in human progress, rather difficult to imagine nowadays, came to a conclusion as one of the darkest and bloodiest centuries in the history of humankind. No other century has known as many violent deaths. But, at least, there is one glimmer of light in this dark period: the birth of the ecumenical movement and ecumenical dialogues. After centuries of growing fragmentation of the XQDVDQFWDHFFOHVLD, the one, holy Church that we profess in our common apostolic creed, into many divided churches, a new movement developed in the opposite direction. In deep sorrow and repentance, all churches realised that their situation of division, so contrary to the will of Christ, was sinful and shameful. It is significant that this new ecumenical awareness developed in the context of the missionary movement, insofar as division was recognised as a major obstacle to world mission, darkening it as a sign and instrument of unity and peace for the world. This is why, in the 20th century, all churches engaged in ecumenical dialogues set out to re-establish the visible unity of all Christians. The foundation of the World Council of Churches in Amsterdam in 1948 represented an important milestone on this ecumenical journey. The Catholic Church abstained at the beginning. The encyclical letters 6DWLVFRJQLWXPof Leo XIII (1896) and 0RUWDOLXPDQLPRV of Pius XI (1928) even condemned the ecumenical dialogue perceived to relativise the claim of the Catholic Church to be the true Church of Jesus Christ. -

“Sacraments Have Theological, Spiritual, Practical, and Societal Premises and Implications. Timothy R. Gabrielli Provides a Me

“Sacraments have theological, spiritual, practical, and societal premises and implications. Timothy R. Gabrielli provides a meticulous investigation of late nineteenth- and twentieth-century ‘streams’ of mystical body theology that illuminate these dimensions. Rather than the oft-used ‘model,’ his more flexible term ‘streams’ readily incorporates his rich analytical foundations and appropriations of mystical body theology, thereby observing similarities and differences among theologians. Gabrielli’s analysis of Virgil Michel’s mystical body theology with nuances from Louis-Marie Chauvet provides a platform to revisit the social and theological implications of sacraments given new realities of a ‘global body.’ Gabrielli’s work also might be used in continued dialogue with the historical practice of that theology in the United States.” —Angelyn Dries, OSF Professor Emerita Saint Louis University “Contributing significantly to our understanding of twentieth-century theology, Gabrielli identifies three streams of mystical body theology: German, Roman, and French. Locating both Virgil Michel and Louis-Marie Chauvet in the French socio-liturgical stream, he brings together pre– and post–Vatican II theologies in a trans-Atlantic perspective that opens out beyond ecclesiology to include Christology, liturgy, social ethics, and fundamental theology, and he offers promise for a renewed mystical body theology. A stunning piece of historical theology and a fruitful frame for future developments!” —William L. Portier Mary Ann Spearin Chair of Catholic -

The Salvation of the Cosmos: Benedict XVI's Eschatology and Its

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 1-1-2017 The alS vation of the Cosmos: Benedict XVI's Eschatology and its Relevance for the Current Ecological Crisis Jeremiah Vallery Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Vallery, J. (2017). The alvS ation of the Cosmos: Benedict XVI's Eschatology and its Relevance for the Current Ecological Crisis (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/205 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SALVATION OF THE COSMOS: BENEDICT XVI’S ESCHATOLOGY AND ITS RELEVANCE FOR THE CURRENT ECOLOGICAL CRISIS A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Jeremiah Vallery December 2017 Copyright by Jeremiah Vallery 2017 THE SALVATION OF THE COSMOS: BENEDICT XVI’S ESCHATOLOGY AND ITS RELEVANCE FOR THE CURRENT ECOLOGICAL CRISIS By Jeremiah Vallery Approved October 30, 2017 ________________________________ Radu Bordeianu, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Theology (Committee Chair) ________________________________ ________________________________ Daniel Scheid, Ph.D. William Wright, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Theology Associate Professor of Theology (Committee Member) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ James Swindal, Ph.D. Marinus Iwuchukwu, Ph.D.