Nature and Purpose of Ecumenical Dialogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa was consecrated as the Roman Catholic Diocesan Bishop of Botucatu in Brazil on December !" #$%&" until certain views he expressed about the treatment of the Brazil’s poor, by both the civil (overnment and the Roman Catholic Church in Brazil caused his removal from the Diocese of Botucatu. His Excellency was subsequently named as punishment as *itular bishop of Maurensi by the late Pope Pius +, of the Roman Catholic Church in #$-.. His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord Carlos Duarte Costa had been a strong advocate in the #$-0s for the reform of the Roman Catholic Church" he challenged many of the 1ey issues such as • Divorce" • challenged mandatory celibacy for the clergy, and publicly stated his contempt re(arding. 2*his is not a theological point" but a disciplinary one 3 Even at this moment in time in an interview with 4ermany's Die 6eit magazine the current Bishop of Rome" Pope Francis is considering allowing married priests as was in the old time including lets not forget married bishops and we could quote many Bishops" Cardinals and Popes over the centurys prior to 8atican ,, who was married. • abuses of papal power, including the concept of Papal ,nfallibility, which the bishop considered a mis(uided and false dogma. His Excellency President 4et9lio Dornelles 8argas as1ed the Holy :ee of Rome for the removal of His Excellency Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa from the Diocese of Botucatu. *he 8atican could not do this directly. 1 | P a g e *herefore the Apostolic Nuncio to Brazil entered into an agreement with the :ecretary of the Diocese of Botucatu to obtain the resi(nation of His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord. -

The Holy See

The Holy See JOHN PAUL II ANGELUS Sunday, 13 October 2002 Dear Brothers and Sisters, 1. I have had the joy these days to welcome His Beatitude Teoctist, the Patriarch of the Orthodox Church of Romania. To him and to all those who accompanied him my heartfelt thanks once again for his deeply appreciated visit. It has brought back the memory of what God allowed me to experience in Bucharest in May 1999. From those meetings there arose a sincere desire for unity. "Unitate" I heard the young people of Bucharest proclaim. Last Monday I heard "Unity" proclaimed again in St Peter's Square, in my first meeting with His Beatitude, the Patriarch. 2. This thirst for full communion among Christians has received remarkable impetus since the Second Vatican Council, which dedicated to ecumenism one of its more important documents, the Decree Unitatis redintegratio. Two days ago we observed the fortieth anniversary of the opening of that historical assembly, called for 11 October 1962, by Pope John XXIII, whom we now revere as Blessed. I had the grace of participating in that event and in my heart I hold valuable and unforgettable memories. In his opening address, Pope John, full of hope and faith, exhorted the Council Fathers to remain faithful to Catholic tradition and to present it again in a way suitable for the new times. In a certain sense, the 11th of October forty years ago marked the solemn and universal beginning of what is called the "new evangelization". 3. The Council represented the "holy door" of that new springtime of the Church that was manifested in the Great Jubilee of the year 2000. -

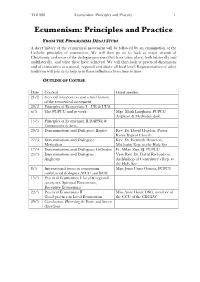

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

Branson-Shaffer-Vatican-II.Pdf

Vatican II: The Radical Shift to Ecumenism Branson Shaffer History Faculty advisor: Kimberly Little The Catholic Church is the world’s oldest, most continuous organization in the world. But it has not lasted so long without changing and adapting to the times. One of the greatest examples of the Catholic Church’s adaptation to the modernization of society is through the Second Vatican Council, held from 11 October 1962 to 8 December 1965. In this gathering of church leaders, the Catholic Church attempted to shift into a new paradigm while still remaining orthodox in faith. It sought to bring the Church, along with the faithful, fully into the twentieth century while looking forward into the twenty-first. Out of the two billion Christians in the world, nearly half of those are Catholic.1 But, Vatican II affected not only the Catholic Church, but Christianity as a whole through the principles of ecumenism and unity. There are many reasons the council was called, both in terms of internal, Catholic needs and also in aiming to promote ecumenism among non-Catholics. There was also an unprecedented event that occurred in the vein of ecumenical beginnings: the invitation of preeminent non-Catholic theologians and leaders to observe the council proceedings. This event, giving outsiders an inside look at 1 World Religions (2005). The Association of Religious Data Archives, accessed 13 April 2014, http://www.thearda.com/QuickLists/QuickList_125.asp. CLA Journal 2 (2014) pp. 62-83 Vatican II 63 _____________________________________________________________ the Catholic Church’s way of meeting modern needs, allowed for more of a reaction from non-Catholics. -

The Holy See

The Holy See LETTER OF HIS HOLINESS POPE FRANCIS TO PARTICIPANTS IN THE PLENARY ASSEMBLY OF THE PONTIFICAL COUNCIL FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN UNITY FOR THE 50th ANNIVERSARY OF THE DECREE "UNITATIS REDINTEGRATIO" [Multimedia] Your Eminences, Dear Brother Bishops and Priests, Dear Brothers and Sisters, I cordially greet you all and thank you for this meeting, which coincides with the 50th anniversary of the promulgation of the Decree of the Second Vatican Council on Ecumenism Unitatis Redintegratio. On that 21st of November 1964 the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen Gentium and the Decree on Catholic Churches of the Eastern Rite Orientalium Ecclesiarum were also promulgated. These three documents taken together, and profoundly linked to one another, offer the vision of Catholic ecclesiology as it was proposed by the Second Vatican Council. That is why you chose to dedicate your sessions to reflecting on how Unitatis Redintegratio can continue to inspire the ecumenical commitment of the Church in today’s changed setting. First of all, we can rejoice in the fact that the Council’s teaching has been broadly received. In these years, on the basis of theological purposes rooted in Scripture and in the Tradition of the Church, the attitude of we Catholics toward Christians of other Churches and ecclesial communities has changed. The hostility and indifference that dug seemingly unbridgeable chasms and caused such deep wounds are now a thing of the past, while a process of healing has begun that permits acceptance of the other as a brother or sister in the profound unity that comes from Baptism. -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC JOURNEY OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI TO BRAZIL ON THE OCCASION OF THE FIFTH GENERAL CONFERENCE OF THE BISHOPS OF LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN MEETING AND CELEBRATION OF VESPERS WITH THE BISHOPS OF BRAZIL ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI Catedral da Sé, São Paulo Friday, 11 May 2007 Dear Brother Bishops! "Although he was the Son of God, he learned obedience through what he suffered; and being made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation to all who obey him." (cf. Heb 5:8-9). 1. The text we have just heard in the Lesson for Vespers contains a profound teaching. Once again we realize that God’s word is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword; it penetrates to the depths of the soul and it grants solace and inspiration to his faithful servants (cf. Heb 4:12). I thank God for the opportunity to be with this distinguished Episcopate, which presides over one of the largest Catholic populations in the world. I greet you with a sense of deep communion and sincere affection, well aware of your devotion to the communities entrusted to your care. The warm reception given to me by the Rector of the Catedral da Sé and by all present has made me feel at home in this great common House which is our Holy Mother, the Catholic Church. 2 I extend a special greeting to the new Officers of the National Conference of Brazilian Bishops and, with gratitude for the kind words of its President, Archbishop Geraldo Lyrio Rocha, I offer prayerful good wishes for his work in deepening communion among the Bishops and in promoting common pastoral activity in a territory of continental dimensions. -

Solidarity and Mediation in the French Stream Of

SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Timothy R. Gabrielli Dayton, Ohio December 2014 SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. APPROVED BY: _________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Anthony J. Godzieba, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Timothy R. Gabrielli All rights reserved 2014 iii ABSTRACT SOLIDARITY MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. In its analysis of mystical body of Christ theology in the twentieth century, this dissertation identifies three major streams of mystical body theology operative in the early part of the century: the Roman, the German-Romantic, and the French-Social- Liturgical. Delineating these three streams of mystical body theology sheds light on the diversity of scholarly positions concerning the heritage of mystical body theology, on its mid twentieth-century recession, as well as on Pope Pius XII’s 1943 encyclical, Mystici Corporis Christi, which enshrined “mystical body of Christ” in Catholic magisterial teaching. Further, it links the work of Virgil Michel and Louis-Marie Chauvet, two scholars remote from each other on several fronts, in the long, winding French stream. -

I MARY for TODAY: RENEWING CATHOLIC MARIAN DEVOTION

MARY FOR TODAY: RENEWING CATHOLIC MARIAN DEVOTION AFTER THE SECOND VATICAN COUNCIL THROUGH ST. LOUIS-MARIE DE MONTFORT’S TRUE DEVOTION TO MARY Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in Theological Studies By Mary Olivia Seeger, B.A. UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio August 2019 i MARY FOR TODAY: RENEWING CATHOLIC MARIAN DEVOTION AFTER THE SECOND VATICAN COUNCIL THROUGH ST. LOUIS-MARIE DE MONTFORT’S TRUE DEVOTION TO MARY Name: Seeger, Mary Olivia APPROVED BY: Elizabeth Groppe, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor Dennis Doyle, Ph.D. Reader Naomi D. DeAnda, Ph.D. Reader Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Department Chair ii © Copyright by Mary Olivia Seeger All rights reserved 2019 iii ABSTRACT MARY FOR TODAY: RENEWING CATHOLIC MARIAN DEVOTION AFTER THE SECOND VATICAN COUNCIL THROUGH ST. LOUIS-MARIE DE MONTFORT’S TRUE DEVOTION TO MARY Name: Seeger, Mary Olivia University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Elizabeth Groppe The purpose and content of my thesis is to investigate and assess how St. Louis- Marie de Montfort’s True Devotion to Mary contributes to a renewal of Marian devotion in the Catholic Church after the Second Vatican Council. My thesis focuses on a close reading of the primary texts of St. Louis-Marie de Montfort (True Devotion to Mary), the Second Vatican Council (Lumen Gentium, the Constitution on the Church), and St. John Paul II (Redemptoris Mater). As part of my theological method, I renewed my Marian consecration and interviewed four other people who currently practice Marian devotion. -

The 18Th International Congress of Jesuit Ecumenists”

“The 18th International Congress of Jesuit Ecumenists” ................................................................. 2 “Conversion to Interreligious Dialogue.....”, James T. Bretzke, S.J. ................................................. 2 “The Practice of Daoist (Taoist) Compassion”, Michael Saso, S.J. .................................................. 3 “Kehilla, Church and Jewish people”, David Neuhaus, S.J. ............................................................. 6 “Let us Cross Over the Other Shore”, Christophe Ravanel, S.J. ………………………………….….10 “Six Theses on Islam in Europe”, Groupe des Deux Rives……………………………………….11 “Meeting of Jesuits in Islamic Studies, September 2006” .............................................................. 13 “Encounter and the Risk of Change”, Wilfried Dettling, S.J. ......................................................... 14 Secretariat for Interreligious Dialogue; Curia S.J., C.P. 6139, 00195 Roma Prati, Italy; N.11 tel. (39) 06.689.77.567/8; fax: 06.689.77.580; e-mail: [email protected] 2006 4 Vatican II, through the conceptual revolution THE 18TH INTERNATIONAL in ecumenical appreciation produced by CONGRESS OF Unitatis Redintegratio, and into the more JESUIT ECUMENISTS recent involvement of Jesuits in the ecumenical movement since the time of the Second Vatican Council. Edward Farrugia The Jesuit Ecumenists are an informal group looks at a specific issue that lies at the heart of Jesuit scholars active in the movement for of Catholic-Orthodox relations, that of the Christian unity who have -

Re-Imagining and Updating Catholicity: Building Church Unity in a Globalized and Scattered World*

Re-imagining and Updating Catholicity: Building Church Unity in a Globalized and Scattered World* SANDRA ARENAS PÉREZ** ABSTRACT ontemporary Catholic theological debate on catholicity claims to recover a qualitative conception of catholicity, in order to correct C the classical emphasis on geographical breadth. The tendencies to iden tify catholicity with universality, to confuse universality with uniformity and to equate continuity with immutability, prevented the Church from developing a holistic approach to catholicity. In facing the challenge of globalization, Christianity can offer an alter native way of togetherness in diversity, which seems to be the current translation of the theological category of the catholicity of the Church. This article’s focus will be therefore on the role and significance of community building and the Church’s unity in regard to sustaining creation and addressing globalization. Key Words: Catholicity, Church Unity, Globalization, Commu nity building, Ecumenism. * This article results of fruitful theological discussions held with some colleagues at the Theology Faculty of the Catholic University of Leuven-Belgium, on the occasion of the International Conference “To Discern Creation in a Scattered World”. A preliminar version, with a stronger emphasis on globalization, was published as part of the memoirs of the above mentioned event: Lernen für das Leben. Perspektiven ökumenischen Lernens und ökumenischer Bildung. Leuven: Lembeck, 2010., p. 187-201 ** Doctor in Systematic Theology, Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium. Adjunct Assis- tant Professor of Systematic Theology, Faculty of Theology, Pontifical Catholic University in Santiago, Chile. E-mail: [email protected] THEOLOGICA XAVERIANA – VOL. 64 NO. 178 (331-351). JULIO-DICIEMBRE 2014. BOGOTÁ, COLOMBIA. -

The Catholic Church and the Ecumenical Movement: Present Experience and Future Prospects Archbishop Mario J Conti

T The Catholic Church and the Ecumenical Movement: Present Experience and Future Prospects Archbishop Mario J Conti It was another place, another continent, in a sense another world. I mean Porto Alegre in southern Brazil where the 9th Assembly of the World Council of Churches was meeting on the campus of the Catholic University. It had been a long journey – in a sense for all of us, not just in reaching the physical venue, but in arriving at this stage in our ecumenical journey. Each one there could tell his or her own personal story of where they had come from and how they had got there, but we were not only there as individuals, we were there as delegates and representatives of Christian Churches, some old and some new, some large and some small, all of them now engaged, whether through the World Council or in partnership with it, in the one ecumenical journey. But since none of us has journeyed alone our experiences can be regarded as in some sense, to a greater or lesser degree, that of the communities to which we belong. My own reflects that of the ecumenical journey of the Catholic Church. When I was ordained, at the Church of San Marcello on the Via del Corso in Rome in the autumn of 1958, it was during a period of sede vacante in the Papacy. Pius XII had just died and John XXIII had yet to be elected. My priesthood, one might say, was born on a cusp. None of us who were ordained that October day could have imagined the roller-coaster ride we were about to experience, propelled by the Holy Spirit and under the steering hand of Angelo Roncalli, who confounded the pundits who had cast him in the role of caretaker Pope, by becoming one of the great reforming pontiffs of the twentieth century. -

A Catholic Response

Theological Studies Faculty Works Theological Studies 3-27-1982 The Image of Mary: A Catholic Response Thomas P. Rausch Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/theo_fac Part of the Catholic Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rausch, Thomas P. “The Image of Mary: A Catholic Response,” America 146 (March 27, 1982): 231-34. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theological Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THOMAS P. RAUSCH to pro •logical The Image of Mary: of the , while .in one A Catholic Response )atical ·arious ecent biblical scholarship has raised scholars involved in the Lutheran-Catholic theological constructions based on Old the question of the gap between the study on Mary offer the following argu Testament models and used to illustrate R Jesus of history and the Christ of ments. particular theological points. To support faith. The Jesus of history is a technical ex The New Testament does not provide a their view they point out, first, that none of pression for Jesus of Nazareth as He was great deal of information about Mary. The the information peculiar to the infancy nar known and experienced by His contempo earliest New Testament writings, the letters ratives (such as Luke's report that John the raries; the Christ of faith refers to the Christ of Paul, mention only that God sent his Baptist was of priestly descent and related of the New Testament recognized and pro Son, "born of a woman, born under the to Jesus) can be clearly verified elsewhere in claimed in faith by the early Christian com law." Many scholars judge the portrayal of the New Testament and, second, that the munities as Lord, Messiah and Son of God.