Presidential Address ECUMENICAL DIALOGUE: the NEXT GENERATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecclesia De Eucharistia on Its Ecumenical Import

Ecumenical & Interfaith Commission: www.melbourne.catholic.org.au/eic Ecclesia de Eucharistia On Its Ecumenical Import By Clint Le Bruyns (Clint Le Bruyns, is an Anglican ecumenist who is currently completing a research project on contemporary Anglican and Protestant perspectives on the Petrine ministry at the University of Stellenbosch in South Africa, where he also serves in the faculty of theology as Assistant Lecturer and Research Development Coordinator of the Beyers Naude Centre for Public Theology.) The pope’s latest encyclical Ecclesia de Eucharistia (On the Eucharist in its Relationship to the Church) – the fourteenth in his 25-year pontificate - was released in Rome on Maundy or Holy Thursday, April 17, 2003.1 Flanked by an introduction (1-10) and conclusion (59-62), the papal letter comprises six critical sections in which the Eucharist is discussed: The Mystery of Faith (11-20); The Eucharist Builds the Church (21-25); The Apostolicity of the Eucharist and of the Church (26-33); The Eucharist and Ecclesial Communion (34-46); The Dignity of the Eucharistic Celebration (47-52); and At the School of Mary, “Woman of the Eucharist” (53-58). Published in English, French, Italian, Spanish, German, Portuguese and Latin, it is a personal, warm, and passionate letter by the current pope on a longstanding theological treasure and dilemma (cf. 8). Like all papal encyclicals it is an internal theological document, bearing the full authority of the Vatican and addressing a matter of grave importance and concern for Roman Catholic faith, life and ministry. But papal texts are no longer merely Roman Catholic in orientation and scope. -

The Holy See

The Holy See VESPERS LITURGY ON THE OCCASION OF THE 40th ANNIVERSARY OF THE PROMULGATION OF THE CONCILIAR DECREE "UNITATIS REDINTEGRATIO" HOMILY OF JOHN PAUL II Saturday, 13 November 2004 "But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near in the blood of Christ. For he is our peace" (Eph 2: 13ff.).1. With these words from his Letter to the Ephesians the Apostle proclaims that Christ is our peace. We are reconciled in him; we are no longer strangers but fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God, built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus himself being the cornerstone (cf. Eph 2: 19ff.).We have listened to Paul's words on the occasion of this celebration that sees us gathered in the venerable Basilica built over the Apostle Peter's tomb. I cordially greet those taking part in the ecumenical conference organized for the 40th anniversary of the promulgation of the Decree Unitatis Redintegratio of the Second Vatican Council. I extend my greeting to the Cardinals, Patriarchs and Bishops taking part, to the Fraternal Delegates of the other Churches and Ecclesial Communities, and to the Consultors, guests and collaborators of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. I thank you for having carefully examined the meaning of this important Decree and the actual and future prospects of the ecumenical movement. This evening we are gathered here to praise God from whom come every good endowment and every perfect gift (cf. Jas 1: 17), and to thank him for the rich fruit the Decree has yielded with the help of the Holy Spirit during these past 40 years.2. -

The Holy See

The Holy See JOHN PAUL II ANGELUS Sunday, 13 October 2002 Dear Brothers and Sisters, 1. I have had the joy these days to welcome His Beatitude Teoctist, the Patriarch of the Orthodox Church of Romania. To him and to all those who accompanied him my heartfelt thanks once again for his deeply appreciated visit. It has brought back the memory of what God allowed me to experience in Bucharest in May 1999. From those meetings there arose a sincere desire for unity. "Unitate" I heard the young people of Bucharest proclaim. Last Monday I heard "Unity" proclaimed again in St Peter's Square, in my first meeting with His Beatitude, the Patriarch. 2. This thirst for full communion among Christians has received remarkable impetus since the Second Vatican Council, which dedicated to ecumenism one of its more important documents, the Decree Unitatis redintegratio. Two days ago we observed the fortieth anniversary of the opening of that historical assembly, called for 11 October 1962, by Pope John XXIII, whom we now revere as Blessed. I had the grace of participating in that event and in my heart I hold valuable and unforgettable memories. In his opening address, Pope John, full of hope and faith, exhorted the Council Fathers to remain faithful to Catholic tradition and to present it again in a way suitable for the new times. In a certain sense, the 11th of October forty years ago marked the solemn and universal beginning of what is called the "new evangelization". 3. The Council represented the "holy door" of that new springtime of the Church that was manifested in the Great Jubilee of the year 2000. -

Branson-Shaffer-Vatican-II.Pdf

Vatican II: The Radical Shift to Ecumenism Branson Shaffer History Faculty advisor: Kimberly Little The Catholic Church is the world’s oldest, most continuous organization in the world. But it has not lasted so long without changing and adapting to the times. One of the greatest examples of the Catholic Church’s adaptation to the modernization of society is through the Second Vatican Council, held from 11 October 1962 to 8 December 1965. In this gathering of church leaders, the Catholic Church attempted to shift into a new paradigm while still remaining orthodox in faith. It sought to bring the Church, along with the faithful, fully into the twentieth century while looking forward into the twenty-first. Out of the two billion Christians in the world, nearly half of those are Catholic.1 But, Vatican II affected not only the Catholic Church, but Christianity as a whole through the principles of ecumenism and unity. There are many reasons the council was called, both in terms of internal, Catholic needs and also in aiming to promote ecumenism among non-Catholics. There was also an unprecedented event that occurred in the vein of ecumenical beginnings: the invitation of preeminent non-Catholic theologians and leaders to observe the council proceedings. This event, giving outsiders an inside look at 1 World Religions (2005). The Association of Religious Data Archives, accessed 13 April 2014, http://www.thearda.com/QuickLists/QuickList_125.asp. CLA Journal 2 (2014) pp. 62-83 Vatican II 63 _____________________________________________________________ the Catholic Church’s way of meeting modern needs, allowed for more of a reaction from non-Catholics. -

The Holy See

The Holy See LETTER OF HIS HOLINESS POPE FRANCIS TO PARTICIPANTS IN THE PLENARY ASSEMBLY OF THE PONTIFICAL COUNCIL FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN UNITY FOR THE 50th ANNIVERSARY OF THE DECREE "UNITATIS REDINTEGRATIO" [Multimedia] Your Eminences, Dear Brother Bishops and Priests, Dear Brothers and Sisters, I cordially greet you all and thank you for this meeting, which coincides with the 50th anniversary of the promulgation of the Decree of the Second Vatican Council on Ecumenism Unitatis Redintegratio. On that 21st of November 1964 the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen Gentium and the Decree on Catholic Churches of the Eastern Rite Orientalium Ecclesiarum were also promulgated. These three documents taken together, and profoundly linked to one another, offer the vision of Catholic ecclesiology as it was proposed by the Second Vatican Council. That is why you chose to dedicate your sessions to reflecting on how Unitatis Redintegratio can continue to inspire the ecumenical commitment of the Church in today’s changed setting. First of all, we can rejoice in the fact that the Council’s teaching has been broadly received. In these years, on the basis of theological purposes rooted in Scripture and in the Tradition of the Church, the attitude of we Catholics toward Christians of other Churches and ecclesial communities has changed. The hostility and indifference that dug seemingly unbridgeable chasms and caused such deep wounds are now a thing of the past, while a process of healing has begun that permits acceptance of the other as a brother or sister in the profound unity that comes from Baptism. -

Ut Unum Sint

ENCYCLICAL LETTER UT UNUM SINT OF THE SUPREME PONTIFF JOHN PAUL II ON COMMITMENT TO ECUMENISM 25 May 1995 INTRODUCTION 1. Ut unum sint! The call for Christian unity made by the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council with such impassioned commitment is finding an ever greater echo in the hearts of believers, especially as the Year 2000 approaches, a year which Christians will celebrate as a sacred Jubilee, the commemoration of the Incarnation of the Son of God, who became man in order to save humanity. The courageous witness of so many martyrs of our century, including members of Churches and Ecclesial Communities not in full communion with the Catholic Church, gives new vigor to the Council’s call and reminds us of our duty to listen to and put into practice its exhortation. These brothers and sisters of ours, united in the selfless offering of their lives for the Kingdom of God, are the most powerful proof that every factor of division can be transcended and overcome in the total gift of self for the sake of the Gospel. Christ calls all his disciples to unity. My earnest desire is to renew this call today, to propose it once more with determination, repeating what I said at the Roman Coliseum on Good Friday 1994, at the end of the meditation on the Via Crucis prepared by my Venerable Brother Bartholomew, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. There I stated that believers in Christ, united in following in the footsteps of the martyrs, cannot remain divided. If they wish truly and effectively to oppose the world’s tendency to reduce to powerlessness the Mystery of Redemption, they must profess together the same truth about the Cross.1 The Cross! An anti-Christian outlook seeks to minimize the Cross, to empty it of its meaning, and to deny that in it man has the source of his new life. -

Gerard Mannion Is to Be Congratulated for This Splendid Collection on the Papacy of John Paul II

“Gerard Mannion is to be congratulated for this splendid collection on the papacy of John Paul II. Well-focused and insightful essays help us to understand his thoughts on philosophy, the papacy, women, the church, religious life, morality, collegiality, interreligious dialogue, and liberation theology. With authors representing a wide variety of perspectives, Mannion avoids the predictable ideological battles over the legacy of Pope John Paul; rather he captures the depth and complexity of this extraordinary figure by the balance, intelligence, and comprehensiveness of the volume. A well-planned and beautifully executed project!” —James F. Keenan, SJ Founders Professor in Theology Boston College Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts “Scenes of the charismatic John Paul II kissing the tarmac, praying with global religious leaders, addressing throngs of adoring young people, and finally dying linger in the world’s imagination. This book turns to another side of this outsized religious leader and examines his vision of the church and his theological positions. Each of these finely tuned essays show the greatness of this man by replacing the mythological account with the historical record. The straightforward, honest, expert, and yet accessible analyses situate John Paul II in his context and show both the triumphs and the ambiguities of his intellectual legacy. This masterful collection is absolutely basic reading for critically appreciating the papacy of John Paul II.” —Roger Haight, SJ Union Theological Seminary New York “The length of John Paul II’s tenure of the papacy, the complexity of his personality, and the ambivalence of his legacy make him not only a compelling subject of study, but also a challenging one. -

A Long-Simmering Tension Over 'Creeping Infallibility' Published on National Catholic Reporter (

A long-simmering tension over 'creeping infallibility' Published on National Catholic Reporter (http://ncronline.org) A long-simmering tension over 'creeping infallibility' May. 09, 2011 Vatican [1] ordinati.jpg [2] Priests lie prostrate before Pope Benedict XVI during their ordination Mass in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican May 7, 2006. (CNS/Chris Helgren) Rome -- When Pope Benedict XVI used the word "infallible" in reference to the ban on women's ordination in a recent letter informing an Australian bishop he'd been sacked, it marked the latest chapter of a long-simmering debate in Catholicism: Exactly where should the boundaries of infallible teaching be drawn? On one side are critics of "creeping infallibility," meaning a steady expansion of the set of church teachings that lie beyond debate. On the other are those, including Benedict, worried about "theological positivism," meaning that there is such a sharp emphasis on formal declarations of infallibility that all other teachings, no matter how constantly or emphatically they've been defined, seem up for grabs. That tension defines the fault lines in many areas of Catholic life, and it also forms part of the background to the recent Australian drama centering on Bishop William Morris of the Toowoomba diocese. Morris was removed from office May 2, apparently on the basis of a 2006 pastoral letter in which he suggested that, in the face of the priest shortage, the church may have to be open to the ordination of women, among other options. Morris has revealed portions of a letter from Benedict informing him of the action, in which the pope says Pope John Paul II defined the teaching on women priests "irrevocably and infallibly." In comments to the Australian media, Morris said that turn of phrase has him concerned about "creeping infallibility." Speaking on background, a Vatican official said this week that the Vatican never comments on the pope's correspondence but has "no reason to doubt" the authenticity of the letter. -

The Obligation of the Christian Faithful to Maintain

THE OBLIGATION OF THE CHRISTIAN FAITHFUL TO MAINTAIN ECCLESIAL COMMUNION WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO ORDINATIO SACERDOTALIS by Cecilia BRENNAN Master’s Seminar – DCA 6395 Prof. John HUELS Faculty of Canon Law Saint Paul University Ottawa 2016 ©Cecilia Brennan, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………3 1 – THE OBLIGATION TO MAINTAIN ECCLESIAL COMMUNION ………5 1.1 – The Development and Revision of canon 209 §1 …………………………...6 1.1.1 The text of the Canon ………………………………..……………… 7 1.1.2 The Terminology in the Canon …………………………….……..….. 7 1.2 – Canonical Analysis of c. 209 §1 ………………………………………..… 9 1.3 –Communio and Related Canonical Issues ………………………………..... 10 1.3.1 Communio and c. 205 …………..…………………………………… 10 1.3.2 Full Communion and Incorporation into the Church ………….…… 11 1.3.3 The Nature of the Obligation in c. 209 §1 ………………………….. 13 2 –THE AUTHENTIC MAGISTERIUM ………………………………………… 16 2.1 – Magisterium ………………………..………………………………….….… 18 2.1.1 Authentic Magisterium …………….…………………………..……. 18 2.1.2 Source of Teaching Authority….…………….………………………. 19 2.2 – Levels of Authentic Magisterial Teachings ………………………..………. 20 2.2.1. Divinely Revealed Dogmas (cc. 749, 750 §1) …………………..… 22 2.2.2 Teachings Closely Related to Divine Revelation (c. 750 §2) ……..... 25 2.2.3. Other Authentic Teachings (cc. 752-753) ………………………….. 26 2.3 – Ordinary and Universal Magisterium ……………………………………….. 27 2.3.1 Sources of Infallibility ………………………………………………. 29 2.3.2 The Object of Infallibility …………………………..…….….……… 30 3 – ORDINATIO SACERDOTALIS ……………………………………………….. 32 3.1 – Authoritative Status of the Teaching in Ordinatio sacerdotalis ……….…. 33 3.1.1 Reactions of the Bishops ……………………………………………..33 3.1.2 Responsum ad propositum dubium ……………..……………………35 3.2 – Authority of the CDF ………………………………………………………37 3.3 – Exercise of the Ordinary and Universal Magisterium …………………..… 39 3.3.1 An Infallible Teaching ………………….……………..……………. -

Re-Imagining and Updating Catholicity: Building Church Unity in a Globalized and Scattered World*

Re-imagining and Updating Catholicity: Building Church Unity in a Globalized and Scattered World* SANDRA ARENAS PÉREZ** ABSTRACT ontemporary Catholic theological debate on catholicity claims to recover a qualitative conception of catholicity, in order to correct C the classical emphasis on geographical breadth. The tendencies to iden tify catholicity with universality, to confuse universality with uniformity and to equate continuity with immutability, prevented the Church from developing a holistic approach to catholicity. In facing the challenge of globalization, Christianity can offer an alter native way of togetherness in diversity, which seems to be the current translation of the theological category of the catholicity of the Church. This article’s focus will be therefore on the role and significance of community building and the Church’s unity in regard to sustaining creation and addressing globalization. Key Words: Catholicity, Church Unity, Globalization, Commu nity building, Ecumenism. * This article results of fruitful theological discussions held with some colleagues at the Theology Faculty of the Catholic University of Leuven-Belgium, on the occasion of the International Conference “To Discern Creation in a Scattered World”. A preliminar version, with a stronger emphasis on globalization, was published as part of the memoirs of the above mentioned event: Lernen für das Leben. Perspektiven ökumenischen Lernens und ökumenischer Bildung. Leuven: Lembeck, 2010., p. 187-201 ** Doctor in Systematic Theology, Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium. Adjunct Assis- tant Professor of Systematic Theology, Faculty of Theology, Pontifical Catholic University in Santiago, Chile. E-mail: [email protected] THEOLOGICA XAVERIANA – VOL. 64 NO. 178 (331-351). JULIO-DICIEMBRE 2014. BOGOTÁ, COLOMBIA. -

The Catholic Church and the Ecumenical Movement: Present Experience and Future Prospects Archbishop Mario J Conti

T The Catholic Church and the Ecumenical Movement: Present Experience and Future Prospects Archbishop Mario J Conti It was another place, another continent, in a sense another world. I mean Porto Alegre in southern Brazil where the 9th Assembly of the World Council of Churches was meeting on the campus of the Catholic University. It had been a long journey – in a sense for all of us, not just in reaching the physical venue, but in arriving at this stage in our ecumenical journey. Each one there could tell his or her own personal story of where they had come from and how they had got there, but we were not only there as individuals, we were there as delegates and representatives of Christian Churches, some old and some new, some large and some small, all of them now engaged, whether through the World Council or in partnership with it, in the one ecumenical journey. But since none of us has journeyed alone our experiences can be regarded as in some sense, to a greater or lesser degree, that of the communities to which we belong. My own reflects that of the ecumenical journey of the Catholic Church. When I was ordained, at the Church of San Marcello on the Via del Corso in Rome in the autumn of 1958, it was during a period of sede vacante in the Papacy. Pius XII had just died and John XXIII had yet to be elected. My priesthood, one might say, was born on a cusp. None of us who were ordained that October day could have imagined the roller-coaster ride we were about to experience, propelled by the Holy Spirit and under the steering hand of Angelo Roncalli, who confounded the pundits who had cast him in the role of caretaker Pope, by becoming one of the great reforming pontiffs of the twentieth century. -

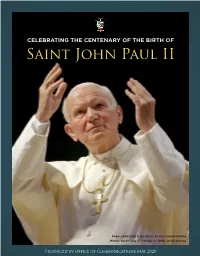

Saint John Paul II

CELEBRATING THE CENTENARY OF THE BIRTH OF Saint John Paul II Pope John Paul II gestures to the crowd during World Youth Day in Denver in 1993. (CNS photo) Produced by Office of Communications May 2020 On April 2, 2020 we commemorated the 15th Anniversary of St. John Paul II’s death and on May 18, 2020, we celebrate the Centenary of his birth. Many of us have special personal We remember his social justice memories of the impact of St. John encyclicals Laborem exercens (1981), Paul II’s ecclesial missionary mysticism Sollicitudo rei socialis (1987) and which was forged in the constant Centesimus annus (1991) that explored crises he faced throughout his life. the rich history and contemporary He planted the Cross of Jesus Christ relevance of Catholic social justice at the heart of every personal and teaching. world crisis he faced. During these We remember his emphasis on the days of COVID-19, we call on his relationship between objective truth powerful intercession. and history. He saw first hand in Nazism We vividly recall his visits to Poland, and Stalinism the bitter and tragic BISHOP visits during which millions of Poles JOHN O. BARRES consequences in history of warped joined in chants of “we want God,” is the fifth bishop of the culture of death philosophies. visits that set in motion the 1989 Catholic Diocese of Rockville In contrast, he asked us to be collapse of the Berlin Wall and a Centre. Follow him on witnesses to the Splendor of Truth, fundamental change in the world. Twitter, @BishopBarres a Truth that, if followed and lived We remember too, his canonization courageously, could lead the world of Saint Faustina, the spreading of global devotion to bright new horizons of charity, holiness and to the Divine Mercy and the establishment of mission.