Ecclesia De Eucharistia – on the Criteria for Intercommunion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecclesia De Eucharistia on Its Ecumenical Import

Ecumenical & Interfaith Commission: www.melbourne.catholic.org.au/eic Ecclesia de Eucharistia On Its Ecumenical Import By Clint Le Bruyns (Clint Le Bruyns, is an Anglican ecumenist who is currently completing a research project on contemporary Anglican and Protestant perspectives on the Petrine ministry at the University of Stellenbosch in South Africa, where he also serves in the faculty of theology as Assistant Lecturer and Research Development Coordinator of the Beyers Naude Centre for Public Theology.) The pope’s latest encyclical Ecclesia de Eucharistia (On the Eucharist in its Relationship to the Church) – the fourteenth in his 25-year pontificate - was released in Rome on Maundy or Holy Thursday, April 17, 2003.1 Flanked by an introduction (1-10) and conclusion (59-62), the papal letter comprises six critical sections in which the Eucharist is discussed: The Mystery of Faith (11-20); The Eucharist Builds the Church (21-25); The Apostolicity of the Eucharist and of the Church (26-33); The Eucharist and Ecclesial Communion (34-46); The Dignity of the Eucharistic Celebration (47-52); and At the School of Mary, “Woman of the Eucharist” (53-58). Published in English, French, Italian, Spanish, German, Portuguese and Latin, it is a personal, warm, and passionate letter by the current pope on a longstanding theological treasure and dilemma (cf. 8). Like all papal encyclicals it is an internal theological document, bearing the full authority of the Vatican and addressing a matter of grave importance and concern for Roman Catholic faith, life and ministry. But papal texts are no longer merely Roman Catholic in orientation and scope. -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC LETTER MANE NOBISCUM DOMINE OF THE HOLY FATHER JOHN PAUL II TO THE BISHOPS, CLERGY AND FAITHFUL FOR THE YEAR OF THE EUCHARIST OCTOBER 2004–OCTOBER 2005 INTRODUCTION 1. “Stay with us, Lord, for it is almost evening” (cf. Lk 24:29). This was the insistent invitation that the two disciples journeying to Emmaus on the evening of the day of the resurrection addressed to the Wayfarer who had accompanied them on their journey. Weighed down with sadness, they never imagined that this stranger was none other than their Master, risen from the dead. Yet they felt their hearts burning within them (cf. v. 32) as he spoke to them and “explained” the Scriptures. The light of the Word unlocked the hardness of their hearts and “opened their eyes” (cf. v. 31). Amid the shadows of the passing day and the darkness that clouded their spirit, the Wayfarer brought a ray of light which rekindled their hope and led their hearts to yearn for the fullness of light. “Stay with us”, they pleaded. And he agreed. Soon afterwards, Jesus' face would disappear, yet the Master would “stay” with them, hidden in the “breaking of the bread” which had opened their eyes to recognize him. 2. The image of the disciples on the way to Emmaus can serve as a fitting guide for a Year when the Church will be particularly engaged in living out the mystery of the Holy Eucharist. Amid our questions and difficulties, and even our bitter disappointments, the divine Wayfarer continues to walk at our side, opening to us the Scriptures and leading us to a deeper understanding of the 2 mysteries of God. -

The Holy See

The Holy See VESPERS LITURGY ON THE OCCASION OF THE 40th ANNIVERSARY OF THE PROMULGATION OF THE CONCILIAR DECREE "UNITATIS REDINTEGRATIO" HOMILY OF JOHN PAUL II Saturday, 13 November 2004 "But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near in the blood of Christ. For he is our peace" (Eph 2: 13ff.).1. With these words from his Letter to the Ephesians the Apostle proclaims that Christ is our peace. We are reconciled in him; we are no longer strangers but fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God, built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus himself being the cornerstone (cf. Eph 2: 19ff.).We have listened to Paul's words on the occasion of this celebration that sees us gathered in the venerable Basilica built over the Apostle Peter's tomb. I cordially greet those taking part in the ecumenical conference organized for the 40th anniversary of the promulgation of the Decree Unitatis Redintegratio of the Second Vatican Council. I extend my greeting to the Cardinals, Patriarchs and Bishops taking part, to the Fraternal Delegates of the other Churches and Ecclesial Communities, and to the Consultors, guests and collaborators of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. I thank you for having carefully examined the meaning of this important Decree and the actual and future prospects of the ecumenical movement. This evening we are gathered here to praise God from whom come every good endowment and every perfect gift (cf. Jas 1: 17), and to thank him for the rich fruit the Decree has yielded with the help of the Holy Spirit during these past 40 years.2. -

The Holy See

The Holy See ADDRESS OF JOHN PAUL II TO THE BISHOPS OF INDIA ON THEIR AD LIMINA VISIT Friday, 23 May 2003 Dear Brother Bishops, 1. As this series of Ad Limina visits of the Latin Rite Bishops of India begins, I warmly welcome you, the Pastors of the Ecclesiastical Provinces of Calcutta, Guwahati, Imphal and Shillong. Together we give thanks to God for the graces bestowed on the Church in your country, and recall the words of our Lord to his disciples as he ascended into heaven: "Lo, I am with you always, to the close of the age" (Mt 28:20). During this Easter Season, you are here at the tombs of Saints Peter and Paul to express again your particular relationship with the universal Church and with the Vicar of Christ. I thank Archbishop Sirkar for the warm sentiments and good wishes he has conveyed on behalf of the Episcopate, clergy, Religious and faithful of the Ecclesiastical Provinces here represented. By God’s grace I have been able to visit your homeland on two occasions and have had first-hand experience of warm Indian hospitality, so much a part of the rich cultural heritage which marks your nation. Since the earliest days of Christianity, India has celebrated the mystery of salvation contained in the Eucharist which mystically joins you with other faith communities in the "oneness of time" of the Paschal Sacrifice (Ecclesia de Eucharistia, 5). I pray that the faithful of India will continue to grow in unity as their participation in the celebration of the Mass confirms them in strength and purpose. -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC JOURNEY OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI TO BRAZIL ON THE OCCASION OF THE FIFTH GENERAL CONFERENCE OF THE BISHOPS OF LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN MEETING AND CELEBRATION OF VESPERS WITH THE BISHOPS OF BRAZIL ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI Catedral da Sé, São Paulo Friday, 11 May 2007 Dear Brother Bishops! "Although he was the Son of God, he learned obedience through what he suffered; and being made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation to all who obey him." (cf. Heb 5:8-9). 1. The text we have just heard in the Lesson for Vespers contains a profound teaching. Once again we realize that God’s word is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword; it penetrates to the depths of the soul and it grants solace and inspiration to his faithful servants (cf. Heb 4:12). I thank God for the opportunity to be with this distinguished Episcopate, which presides over one of the largest Catholic populations in the world. I greet you with a sense of deep communion and sincere affection, well aware of your devotion to the communities entrusted to your care. The warm reception given to me by the Rector of the Catedral da Sé and by all present has made me feel at home in this great common House which is our Holy Mother, the Catholic Church. 2 I extend a special greeting to the new Officers of the National Conference of Brazilian Bishops and, with gratitude for the kind words of its President, Archbishop Geraldo Lyrio Rocha, I offer prayerful good wishes for his work in deepening communion among the Bishops and in promoting common pastoral activity in a territory of continental dimensions. -

Ut Unum Sint

ENCYCLICAL LETTER UT UNUM SINT OF THE SUPREME PONTIFF JOHN PAUL II ON COMMITMENT TO ECUMENISM 25 May 1995 INTRODUCTION 1. Ut unum sint! The call for Christian unity made by the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council with such impassioned commitment is finding an ever greater echo in the hearts of believers, especially as the Year 2000 approaches, a year which Christians will celebrate as a sacred Jubilee, the commemoration of the Incarnation of the Son of God, who became man in order to save humanity. The courageous witness of so many martyrs of our century, including members of Churches and Ecclesial Communities not in full communion with the Catholic Church, gives new vigor to the Council’s call and reminds us of our duty to listen to and put into practice its exhortation. These brothers and sisters of ours, united in the selfless offering of their lives for the Kingdom of God, are the most powerful proof that every factor of division can be transcended and overcome in the total gift of self for the sake of the Gospel. Christ calls all his disciples to unity. My earnest desire is to renew this call today, to propose it once more with determination, repeating what I said at the Roman Coliseum on Good Friday 1994, at the end of the meditation on the Via Crucis prepared by my Venerable Brother Bartholomew, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. There I stated that believers in Christ, united in following in the footsteps of the martyrs, cannot remain divided. If they wish truly and effectively to oppose the world’s tendency to reduce to powerlessness the Mystery of Redemption, they must profess together the same truth about the Cross.1 The Cross! An anti-Christian outlook seeks to minimize the Cross, to empty it of its meaning, and to deny that in it man has the source of his new life. -

Ad Orientem” at St

Liturgical Catechesis on “Ad Orientem” at St. John the Beloved “In Testimonium” Parish Bulletin Articles from October 2015 to May 2016 CITATIONS OF LITURGICAL DOCUMENTS IN ST. JOHN THE BELOVED PARISH BULLETIN Cardinal Sarah Speech at Sacra Liturgia USA 2015 (2015-10-18) SC 2.4 (2015-10-27) SC 7.8 (2015-11-01) SC 9 (2015-11-08) SC 11.12 (2015-11-15) Ecclesia de Eucharistia (2015-11-29) Ecclesia de Eucharistia (2015-12-06) Ecclesia de Eucharistia (2015-12-13) Sacramentum Caritatis, 20 (2016-01-31) Sacramentum Caritatis, 21 (2016-02-07) Sacramentum Caritatis, 55 (2016-02-14) Sacramentum Caritatis, 52 & 53a (2016-02-21) Sacramentum Caritatis, 53b & 38 (2016-02-28) “Silenziosa azione del cuore”, Cardinal Sarah, (2016-03-06) “Silenziosa azione del cuore”, Cardinal Sarah, (2016-03-13) “Silenziosa azione del cuore”, Cardinal Sarah, (2016-03-20) Spirit of the Liturgy, Cardinal Ratzinger, (2016-04-10) Roman Missal (2016-04-17) IN TESTIMONIUM… 18 OCTOBER 2015 Among my more memorable experiences of the visit of the Holy Father to the United States were the rehearsals for the Mass of Canonization. At the beginning of the second rehearsal I attended one of the Assistant Papal Masters of Ceremony, Monsignor John Cihak, addressed all the servers and other volunteers. He is a priest of the Archdiocese of Portland in Oregon and also a seminary classmate of mine. Monsignor reminded all present that the primary protagonist in the Sacred Liturgy is the Holy Trinity. From that he expounded on the nature of reverence, both as a matter of interior activity and exterior stillness. -

(Mk 1:22). on the Role of Wonderment in the Theological Method

Teologia w Polsce 14,2 (2020), s. 49–62 10.31743/twp.2020.14.2.03 Fr. Cezary Smuniewski* Akademia Sztuki Wojennej, Warszawa “ET STUPEBANT SUPER DOCTRINA EJUS” (MK 1:22). ON THE ROLE OF WONDERMENT IN THE THEOLOGICAL METHOD The study is a contribution to research on the theological method and shows the motif of wonderment in the teaching and poetry of John Paul II as an experience inviting man to get to know God and His works ever more deeply. The human experience of being amazed with God has been presented as a theological event – a grace of the ability to stand in awe of God, to get closer to Him and to speak about Him. The author of the article comes to the conclusion that the mission of a theologian is inseparably connected with cultivating the ability to be amazed with God and His works. The experience of wonderment is one of the elements leading to communion with Christ the Theologian, who reveals the Father. INTRODUCTION The aim of this study is to show the motif of wonderment and at the same time to try to recognize in this motif the content that can be useful in research on the theological method and thus indirectly on the mission of the theologian. The choice of sources which became the basis for the analysis was determined by the main idea – striving to show wonderment as one of the elements influencing the theological thinking and the experience of faith. The quoted documents and studies were selected with regard to their relation to the theological and semantic problem space, defined by the main goal. -

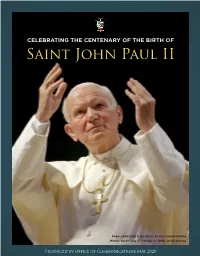

Saint John Paul II

CELEBRATING THE CENTENARY OF THE BIRTH OF Saint John Paul II Pope John Paul II gestures to the crowd during World Youth Day in Denver in 1993. (CNS photo) Produced by Office of Communications May 2020 On April 2, 2020 we commemorated the 15th Anniversary of St. John Paul II’s death and on May 18, 2020, we celebrate the Centenary of his birth. Many of us have special personal We remember his social justice memories of the impact of St. John encyclicals Laborem exercens (1981), Paul II’s ecclesial missionary mysticism Sollicitudo rei socialis (1987) and which was forged in the constant Centesimus annus (1991) that explored crises he faced throughout his life. the rich history and contemporary He planted the Cross of Jesus Christ relevance of Catholic social justice at the heart of every personal and teaching. world crisis he faced. During these We remember his emphasis on the days of COVID-19, we call on his relationship between objective truth powerful intercession. and history. He saw first hand in Nazism We vividly recall his visits to Poland, and Stalinism the bitter and tragic BISHOP visits during which millions of Poles JOHN O. BARRES consequences in history of warped joined in chants of “we want God,” is the fifth bishop of the culture of death philosophies. visits that set in motion the 1989 Catholic Diocese of Rockville In contrast, he asked us to be collapse of the Berlin Wall and a Centre. Follow him on witnesses to the Splendor of Truth, fundamental change in the world. Twitter, @BishopBarres a Truth that, if followed and lived We remember too, his canonization courageously, could lead the world of Saint Faustina, the spreading of global devotion to bright new horizons of charity, holiness and to the Divine Mercy and the establishment of mission. -

Ecclesia De Eucharistia: Encyclical Letter Free Ebook

ON THE EUCHARIST: ECCLESIA DE EUCHARISTIA: ENCYCLICAL LETTER DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK John Paul II | 68 pages | 01 Jun 2003 | USCCB | 9781574555592 | English | Washington, DC, United States Reflections on Ecclesia de Eucharistia - 1 Their content was later to converge in the documents of the Second Vatican Council, especially Lumen Gentium and Sacrosanctum Concilium. If, in the presence of this mystery, reason experiences its limits, the heart, enlightened by the grace of the Holy Spirit, clearly sees the response that is demanded, and bows low in adoration and unbounded love. Here is the Church's treasure, the heart of the world, the pledge of the fulfilment for which each man and woman, even unconsciously, yearns. So it was his Passover meal. The introduction opens with the words "The Church draws her life from the Eucharist. The same Decree, in No. In Communion, Christ offers himself as nourishment, which "spurs us on our journey through history and plants a seed of living hope in our daily commitment to the work before us". The worship of the Eucharist outside of the Mass is of inestimable value for the life of the Church. All these things express Christ's wish that his last supper would be enlivened by sincere love, by an intimate union of hearts. In this Encyclical, he takes On the Eucharist: Ecclesia de Eucharistia: Encyclical Letter the thread of that discourse to clarify certain points and dispel certain doubts that have arisen here and there concerning the Eucharistic Mystery. This practice, repeatedly praised and recommended by the Magisterium, 49 is supported by the example of many saints. -

The Ecumenical Legacy of Saint John Paul II: a Providential Vision of Christian Division, a Prophetic Vision of Christian Unity

The Ecumenical Legacy of Saint John Paul II: A Providential Vision of Christian Division, a Prophetic Vision of Christian Unity Hyacinthe Destivelle, O.P. Talk for the 2020 Father Val Ambrose McInnes Chair Angelicum Donor Homecoming Twenty–five years ago, on 25 May 1995, on the Feast of the Ascension, Saint John Paul II published his milestone encyclical Ut unum sint on the ecumenical commitment. Thirty years after the end of the Second Vatican Council, he reiterated that the Catholic Church is committed “irrevocably” to following the path of the ecumenical venture (UUS 3) and “embraces with hope the commitment to ecumenism as a duty of the Christian conscience enlightened by faith and guided by love” (UUS 8). The jubilee of the encyclical, which coincides with the centenary of the birth of John Paul II, is an opportunity to enquire into the contribution to ecumenism of the first Slavic 1 pope. Readily recalling that he came from a country with a deep ecumenical tradition, John Paul II liked to repeat that the restoration of Christian unity was “one of the first and major 2 tasks of [his] pontificate”. Not only did John Paul II write the first papal encyclical on ecumenism, in which for the first time a pope invited pastors and theologians of the various churches to seek the forms in which his ministry of unity “may accomplish a service of love recognized by all concerned” (UUS 95), but he accomplished many prophetic gestures: for example, he was the first pope to preach at the Lutheran church in Rome (1983) and to visit countries of Orthodox tradition (Romania and Georgia in 1999, Greece and Ukraine in 2001, Bulgaria in 2002). -

Bibliography on the Mass

Bibliography on The Mass Magisterial Documents: Catechism of the Catholic Church, #s 1322-1419. United States Catholic Catechism for Adults, esp. Chapter 17 on the Eucharist Sacred Scripture Documents of Vatican II: The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy (Sacrosanctum Concilium). Specifically #s 1-11, 47-58. Instruction on the Worship of the Eucharistic Mystery (Eucharisticum Mysterium). Writings of Venerable John Paul II: John Paul II: Apostolic Letter Dies Domini, (1998). John Paul II. Apostolic Letter Dominicae Cenae , (1980). John Paul II: Encyclical Letter Ecclesia de Eucharistia, (2003). John Paul II: Apostolic Letter Mane Nobiscum Domine (2004). Writings of Pope Benedict XVI: Joseph Ratzinger. Feast of Faith: Approaches to a Theology of the Liturgy (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1986). Joseph Ratzinger. God is Near Us: The Eucharist, the Heart of Faith (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2003). Joseph Ratzinger. Pilgrim Fellowship of Faith: The Church as Communion (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2005). Joseph Ratzinger: The Spirit of the Liturgy (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2000). Pope Benedict XVI. Apostolic Exhortation Sacramentum Caritatis, (2007). Additional Works of Interest: Fr. Walter Burghardt’s homily, “No Love, No Eucharist.” Cardinal John O’Connor, “Homily on the Eucharist from Palm Sunday Mass, 1998.” Books: Raniero Cantalamessa. The Eucharist: Our Sanctification (Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, 1995). Jeremy Driscoll. Theology at the Eucharistic Table: Master Themes in the Eucharistic Tradition (Leominster: Gracewing, 2003). Michael Gaudoin-Parker. The Real Presence through the Ages (New York: Alba House, 1993). Thomas Howard. Evangelical is Not Enough: Worship of God in Liturgy and Sacrament (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1984). Raymond Moloney. Our Splendid Eucharist: Reflections on Mass and Sacrament (Dublin: Veritas, 2003).