Ii. Teologia W Perspektywie Ekumenii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecclesia De Eucharistia on Its Ecumenical Import

Ecumenical & Interfaith Commission: www.melbourne.catholic.org.au/eic Ecclesia de Eucharistia On Its Ecumenical Import By Clint Le Bruyns (Clint Le Bruyns, is an Anglican ecumenist who is currently completing a research project on contemporary Anglican and Protestant perspectives on the Petrine ministry at the University of Stellenbosch in South Africa, where he also serves in the faculty of theology as Assistant Lecturer and Research Development Coordinator of the Beyers Naude Centre for Public Theology.) The pope’s latest encyclical Ecclesia de Eucharistia (On the Eucharist in its Relationship to the Church) – the fourteenth in his 25-year pontificate - was released in Rome on Maundy or Holy Thursday, April 17, 2003.1 Flanked by an introduction (1-10) and conclusion (59-62), the papal letter comprises six critical sections in which the Eucharist is discussed: The Mystery of Faith (11-20); The Eucharist Builds the Church (21-25); The Apostolicity of the Eucharist and of the Church (26-33); The Eucharist and Ecclesial Communion (34-46); The Dignity of the Eucharistic Celebration (47-52); and At the School of Mary, “Woman of the Eucharist” (53-58). Published in English, French, Italian, Spanish, German, Portuguese and Latin, it is a personal, warm, and passionate letter by the current pope on a longstanding theological treasure and dilemma (cf. 8). Like all papal encyclicals it is an internal theological document, bearing the full authority of the Vatican and addressing a matter of grave importance and concern for Roman Catholic faith, life and ministry. But papal texts are no longer merely Roman Catholic in orientation and scope. -

The Holy See

The Holy See VESPERS LITURGY ON THE OCCASION OF THE 40th ANNIVERSARY OF THE PROMULGATION OF THE CONCILIAR DECREE "UNITATIS REDINTEGRATIO" HOMILY OF JOHN PAUL II Saturday, 13 November 2004 "But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near in the blood of Christ. For he is our peace" (Eph 2: 13ff.).1. With these words from his Letter to the Ephesians the Apostle proclaims that Christ is our peace. We are reconciled in him; we are no longer strangers but fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God, built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus himself being the cornerstone (cf. Eph 2: 19ff.).We have listened to Paul's words on the occasion of this celebration that sees us gathered in the venerable Basilica built over the Apostle Peter's tomb. I cordially greet those taking part in the ecumenical conference organized for the 40th anniversary of the promulgation of the Decree Unitatis Redintegratio of the Second Vatican Council. I extend my greeting to the Cardinals, Patriarchs and Bishops taking part, to the Fraternal Delegates of the other Churches and Ecclesial Communities, and to the Consultors, guests and collaborators of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. I thank you for having carefully examined the meaning of this important Decree and the actual and future prospects of the ecumenical movement. This evening we are gathered here to praise God from whom come every good endowment and every perfect gift (cf. Jas 1: 17), and to thank him for the rich fruit the Decree has yielded with the help of the Holy Spirit during these past 40 years.2. -

Ut Unum Sint

ENCYCLICAL LETTER UT UNUM SINT OF THE SUPREME PONTIFF JOHN PAUL II ON COMMITMENT TO ECUMENISM 25 May 1995 INTRODUCTION 1. Ut unum sint! The call for Christian unity made by the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council with such impassioned commitment is finding an ever greater echo in the hearts of believers, especially as the Year 2000 approaches, a year which Christians will celebrate as a sacred Jubilee, the commemoration of the Incarnation of the Son of God, who became man in order to save humanity. The courageous witness of so many martyrs of our century, including members of Churches and Ecclesial Communities not in full communion with the Catholic Church, gives new vigor to the Council’s call and reminds us of our duty to listen to and put into practice its exhortation. These brothers and sisters of ours, united in the selfless offering of their lives for the Kingdom of God, are the most powerful proof that every factor of division can be transcended and overcome in the total gift of self for the sake of the Gospel. Christ calls all his disciples to unity. My earnest desire is to renew this call today, to propose it once more with determination, repeating what I said at the Roman Coliseum on Good Friday 1994, at the end of the meditation on the Via Crucis prepared by my Venerable Brother Bartholomew, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. There I stated that believers in Christ, united in following in the footsteps of the martyrs, cannot remain divided. If they wish truly and effectively to oppose the world’s tendency to reduce to powerlessness the Mystery of Redemption, they must profess together the same truth about the Cross.1 The Cross! An anti-Christian outlook seeks to minimize the Cross, to empty it of its meaning, and to deny that in it man has the source of his new life. -

Method in American Catholic Moral Eology a Er Veritatis Splendor

Journal of Moral eology, Vol. 1, No. 1 (2012): 170-192 REVIEW ESSAY Method in American Catholic Moral eology Aer Veritatis Splendor DAVID CLOUTIER and WILLIAM C. MATTISON III UR PURPOSE in this inaugural issue of the Journal of Moral eology is to reflect on the state of“ method” in Catholic moral theology today. But rather than present a set of essays, each representing a different method or “Oschool,” we chose to invite authors at institutions training American Catholic moral theologians to write essays reflecting on the influence of a diverse set of thinkers, thinkers who both immediately preceded and particularly influenced American Catholic moral theology today. We hope that presenting a set of essays by these current shapers of American Catholic moral theologians, about recent influential fig- ures, will provide a lens into what characterizes Catholic moral the- ology today. So, does this decision about how to reflect on methodology reveal that American Catholic moral theology today in fact has no “meth- od”? Certainly as compared with pre-Vatican II Catholic theology of all subdisciplines, which Gerard McCool describes as marked by a “search for a unitary method,”1 moral theology today does not pre- sent a straightforward unified methodology. Yet to say “there is no method” says too little. Such a claim could wrongly suggest that there 1 Gerard McCool, Nineteenth Century Scholasticism: e Search for a Unitary Meth- od (New York: Fordham University Press, 1989). Method in American Catholic Moral eology 171 are no identifiable parameters in the discipline of Catholic moral theology today. It could also fan the flames of a reactionary trend seeking refuge in the perceived order of pre-Vatican II moral theolo- gy, a move that, moreover, has no real support in the work of Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI. -

The Holy See

The Holy See IOANNES PAULUS PP. II EVANGELIUM VITAE To the Bishops Priests and Deacons Men and Women religious lay Faithful and all People of Good Will on the Value and Inviolability of Human Life INTRODUCTION 1. The Gospel of life is at the heart of Jesus' message. Lovingly received day after day by the Church, it is to be preached with dauntless fidelity as "good news" to the people of every age and culture. At the dawn of salvation, it is the Birth of a Child which is proclaimed as joyful news: "I bring you good news of a great joy which will come to all the people; for to you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, who is Christ the Lord" (Lk 2:10-11). The source of this "great joy" is the Birth of the Saviour; but Christmas also reveals the full meaning of every human birth, and the joy which accompanies the Birth of the Messiah is thus seen to be the foundation and fulfilment of joy at every child born into the world (cf. Jn 16:21). When he presents the heart of his redemptive mission, Jesus says: "I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly" (Jn 10:10). In truth, he is referring to that "new" and "eternal" life 2 which consists in communion with the Father, to which every person is freely called in the Son by the power of the Sanctifying Spirit. It is precisely in this "life" that all the aspects and stages of human life achieve their full significance. -

The Holy See

The Holy See MESSAGE OF THE HOLY FATHER ON THE OCCASION OF THE 14TH WORLD YOUTH DAY “The Father loves you” (cf. Jn 16:27) Dear young friends! 1. In the perspective of the Jubilee which is now drawing near, 1999 is aimed at “broadening the horizons of believers so that they will see things in the perspective of Christ: in the perspective of the 'Father who is in heaven' from whom the Lord was sent and to whom he has returned” (Tertio Millennio Adveniente, 49). It is, indeed, not possible to celebrate Christ and his jubilee without turning, with him, towards God, his Father and our Father (cf. Jn 20:17). The Holy Spirit also takes us back to the Father and to Jesus. If the Spirit teaches us to say: “Jesus is Lord” (cf. 1Cor 12:3), it is to make us capable of speaking with God, calling him “Abba! Father!” (cf. Gal 4:6). I invite you also, together with the whole Church, to turn towards God the Father and to listen with gratitude and wonder to the amazing revelation of Jesus: “The Father loves you!” (cf. Jn 16:27). These are the words I entrust to you as theme for the XIV World Youth Day. Dear young people, receive the love that God first gives you (cf. 1Jn 4:19). Hold fast to this certainty, the only one that can give meaning, strength and joy to life: his love will never leave you, his covenant of peace will never be removed from you (cf. Is 54:10). -

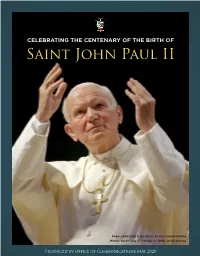

Saint John Paul II

CELEBRATING THE CENTENARY OF THE BIRTH OF Saint John Paul II Pope John Paul II gestures to the crowd during World Youth Day in Denver in 1993. (CNS photo) Produced by Office of Communications May 2020 On April 2, 2020 we commemorated the 15th Anniversary of St. John Paul II’s death and on May 18, 2020, we celebrate the Centenary of his birth. Many of us have special personal We remember his social justice memories of the impact of St. John encyclicals Laborem exercens (1981), Paul II’s ecclesial missionary mysticism Sollicitudo rei socialis (1987) and which was forged in the constant Centesimus annus (1991) that explored crises he faced throughout his life. the rich history and contemporary He planted the Cross of Jesus Christ relevance of Catholic social justice at the heart of every personal and teaching. world crisis he faced. During these We remember his emphasis on the days of COVID-19, we call on his relationship between objective truth powerful intercession. and history. He saw first hand in Nazism We vividly recall his visits to Poland, and Stalinism the bitter and tragic BISHOP visits during which millions of Poles JOHN O. BARRES consequences in history of warped joined in chants of “we want God,” is the fifth bishop of the culture of death philosophies. visits that set in motion the 1989 Catholic Diocese of Rockville In contrast, he asked us to be collapse of the Berlin Wall and a Centre. Follow him on witnesses to the Splendor of Truth, fundamental change in the world. Twitter, @BishopBarres a Truth that, if followed and lived We remember too, his canonization courageously, could lead the world of Saint Faustina, the spreading of global devotion to bright new horizons of charity, holiness and to the Divine Mercy and the establishment of mission. -

Topical Index

298 The Moral Life in Christ Index Page numbers in color indicate illustrations. Titles of paintings will be found under the name of the artist, unless they are anonymous. References to specific citations from Scripture and the Catechism will be found in the separate INDEX OF CITATIONS. A art and music in Church, 130 sanctifying grace in, 33, 34, atheism, 119, 124 235, 250–252, 287, 288 attractiveness. See sexuality Barzotti, Biagio, Pope abortion and abortion laws, Leo XIII with Cardinals St. Augustine of Hippo 50, 82, 88, 90–91, 103 Rampolla, Parochi, on Baptism, 43 Abraham, 103 Bonaparte, and Sacconi (ca. Benedict XVI on, 14 absolution, 148, 286 1890), 114 Champaigne, Philippe de, abstinence, 99, 175, 286 Baudricourt, Robert, 239 Saint Augustine (ca. 1650), Baumgartner, Johan acedia, 66, 286 212 Wolfgang, The Prodigal Son actual grace, 235, 286 Confessions, 12 Wasting his Inheritance (1724- Adam and Eve on Eternal Law, 58–59 1761), 6 marriage and, 108 on freedom, 9 beatitude, 34, 120, 193. See Original Justice and, 19 on grace, 246 also holiness Original Sin and, 17–22, 24, on happiness, 47 Beatitudes, 145, 147–150, 26, 33, 206, 293 152–154, 161, 165, 286 life of, 7 adoration, 275, 277, 286 Benedict XVI (pope) on love, 89 adulation, 129, 130, 286 Caritas in Veritate (papal passions and, 212 adultery, 93, 94, 102, 286 encyclical, 2009), 117–118 on prayer, 283 alcohol and drugs, 84, 141 Deus Caritas Est (papal Retractationes, 28 encyclical, 2005), 13–14 almsgiving, 123, 257, 286 On the Sermon on the general audience, Nov. -

The Ecumenical Legacy of Saint John Paul II: a Providential Vision of Christian Division, a Prophetic Vision of Christian Unity

The Ecumenical Legacy of Saint John Paul II: A Providential Vision of Christian Division, a Prophetic Vision of Christian Unity Hyacinthe Destivelle, O.P. Talk for the 2020 Father Val Ambrose McInnes Chair Angelicum Donor Homecoming Twenty–five years ago, on 25 May 1995, on the Feast of the Ascension, Saint John Paul II published his milestone encyclical Ut unum sint on the ecumenical commitment. Thirty years after the end of the Second Vatican Council, he reiterated that the Catholic Church is committed “irrevocably” to following the path of the ecumenical venture (UUS 3) and “embraces with hope the commitment to ecumenism as a duty of the Christian conscience enlightened by faith and guided by love” (UUS 8). The jubilee of the encyclical, which coincides with the centenary of the birth of John Paul II, is an opportunity to enquire into the contribution to ecumenism of the first Slavic 1 pope. Readily recalling that he came from a country with a deep ecumenical tradition, John Paul II liked to repeat that the restoration of Christian unity was “one of the first and major 2 tasks of [his] pontificate”. Not only did John Paul II write the first papal encyclical on ecumenism, in which for the first time a pope invited pastors and theologians of the various churches to seek the forms in which his ministry of unity “may accomplish a service of love recognized by all concerned” (UUS 95), but he accomplished many prophetic gestures: for example, he was the first pope to preach at the Lutheran church in Rome (1983) and to visit countries of Orthodox tradition (Romania and Georgia in 1999, Greece and Ukraine in 2001, Bulgaria in 2002). -

The Use of Philosophical Principles in Catholic Social Thought: the Case of Gaudium Et Spes

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 45 Number 2 Volume 45, 2006, Number 2 Article 6 The Use of Philosophical Principles in Catholic Social Thought: The Case of Gaudium et Spes Rev. Joseph W. Koterski, S.J. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls Part of the Catholic Studies Commons This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE USE OF PHILOSOPHICAL PRINCIPLES IN CATHOLIC SOCIAL THOUGHT: THE CASE OF GAUDIUM ET SPES REVEREND JOSEPH W. KOTERSKI, S.J.t It is common to find individuals who are very attracted to questions of social justice and others quite uninterested, or even suspicious.1 At both extremes there are dangers to avoid. On the one hand, Catholicism may never be reduced to the concerns of "the social gospel" apart from the rest of the faith.2 On the other hand, the Church's social teachings, especially in the clear articulation given by recent popes and the Second Vatican Council, are not peripheral to the faith, not something purely optional, as if the essence of Catholicism were a matter of spirituality to the exclusion of morality.3 Like the rest of Catholic moral theology, Catholic Social Teaching (CST) has roots both in revelation and reason,4 and anyone interested in t Rev. Joseph W. -

Ecclesia De Eucharistia – on the Criteria for Intercommunion

Le Bruyns, C University of Stellenbosch Ecclesia de Eucharistia – on the criteria for intercommunion ABSTRACT In contemporary ecumenism, papal encyclicals are read and assessed as ecumenical theological statements on matters of grave importance. Ecclesia de Eucharistia, released in April 2003, is penned by John Paul II and concerns itself with the Eucharist and its relationship to the Church. Since the day it was released, various initial reactions from different Christian churches have begun pouring in. Virtually all of these statements highlight what the respective denominations identify as the most critical as well as lamentable section: the pope’s remarks on the longstanding ecumenical discourse on Eucharistic hospitality (or sharing). This article focuses on Ecclesia de Eucharistia for an ecumenical critique of the relevant statements around intercommunion as well as its impact on future ecumenical relations. 1. INTRODUCTION During the afternoon celebration of the Mass of the Lord’s Supper on Maundy (or Holy) Thursday in Rome, April 17, 2003, the current pope signed his latest encyclical letter Ecclesia de Eucharistia (On the Eucharist in its relationship to the Church). This internal papal document is addressed to “the Bishops, Priests and Deacons, Men and Women in the Consecrated Life and All the Lay Faithful on the Eucharist and Its Relationship to the Church” and has been published to this point in English, German, Italian, Latin, Spanish, French and Portuguese. It is clearly a warm but firm theological statement on the meaning and role of the Eucharist, comprising an introduction (§ 1- 1 10), six chapters (§ 11-58), and a conclusion (§ 59-62). -

Pastoral Letter on the Reading of Amoris Laetitia In

PASTORAL LETTER ON THE READING OF AMORIS LAETITIA IN LIGHT OF CHURCH TEACHING “A TRUE AND LIVING ICON” OF THE ARCHBISHOP OF PORTLAND, OREGON MOST REVEREND ALEXANDER K. SAMPLE TO THE PRIESTS, DEACONS, RELIGIOUS AND FAITHFUL OF THE ARCHDIOCESE “The couple that loves and begets life is a true, living icon … capable of revealing God the Creator and Savior.”1 With these words our Holy Father, Pope Francis, reminds us that married love is “a symbol of God’s inner life,” for the “triune God is a communion of love, and the family is its living reflection.”2 Of its very nature, marriage exists for the communion of life and love between spouses, ordered to the procreation and care of children, in an exclusive and permanent bond between one man and one woman. In this natural bond, existing even between unbaptized spouses, we are given “an image for understanding and describing the mystery of God himself.…”3 Christ our Lord elevated the natural bond of marriage to the dignity of a sacrament whereby the union of man and woman signifies the “union of Christ and the Church.”4 God, who is eternal and unchanging, gives marriage as a natural icon of himself; Christ elevates marriage into a sacrament signifying the permanent, indissoluble covenant with his people. Because the family is essential to the well-being of the world, the Church, and the spread of the Gospel, the world’s bishops gathered in the Synods of 2014 and 2015 to identify the real situation of marriages and families in the world today and to seek pastoral solutions for these challenges.