Method in American Catholic Moral Eology a Er Veritatis Splendor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Holy See

The Holy See IOANNES PAULUS PP. II EVANGELIUM VITAE To the Bishops Priests and Deacons Men and Women religious lay Faithful and all People of Good Will on the Value and Inviolability of Human Life INTRODUCTION 1. The Gospel of life is at the heart of Jesus' message. Lovingly received day after day by the Church, it is to be preached with dauntless fidelity as "good news" to the people of every age and culture. At the dawn of salvation, it is the Birth of a Child which is proclaimed as joyful news: "I bring you good news of a great joy which will come to all the people; for to you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, who is Christ the Lord" (Lk 2:10-11). The source of this "great joy" is the Birth of the Saviour; but Christmas also reveals the full meaning of every human birth, and the joy which accompanies the Birth of the Messiah is thus seen to be the foundation and fulfilment of joy at every child born into the world (cf. Jn 16:21). When he presents the heart of his redemptive mission, Jesus says: "I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly" (Jn 10:10). In truth, he is referring to that "new" and "eternal" life 2 which consists in communion with the Father, to which every person is freely called in the Son by the power of the Sanctifying Spirit. It is precisely in this "life" that all the aspects and stages of human life achieve their full significance. -

The Holy See

The Holy See MESSAGE OF THE HOLY FATHER ON THE OCCASION OF THE 14TH WORLD YOUTH DAY “The Father loves you” (cf. Jn 16:27) Dear young friends! 1. In the perspective of the Jubilee which is now drawing near, 1999 is aimed at “broadening the horizons of believers so that they will see things in the perspective of Christ: in the perspective of the 'Father who is in heaven' from whom the Lord was sent and to whom he has returned” (Tertio Millennio Adveniente, 49). It is, indeed, not possible to celebrate Christ and his jubilee without turning, with him, towards God, his Father and our Father (cf. Jn 20:17). The Holy Spirit also takes us back to the Father and to Jesus. If the Spirit teaches us to say: “Jesus is Lord” (cf. 1Cor 12:3), it is to make us capable of speaking with God, calling him “Abba! Father!” (cf. Gal 4:6). I invite you also, together with the whole Church, to turn towards God the Father and to listen with gratitude and wonder to the amazing revelation of Jesus: “The Father loves you!” (cf. Jn 16:27). These are the words I entrust to you as theme for the XIV World Youth Day. Dear young people, receive the love that God first gives you (cf. 1Jn 4:19). Hold fast to this certainty, the only one that can give meaning, strength and joy to life: his love will never leave you, his covenant of peace will never be removed from you (cf. Is 54:10). -

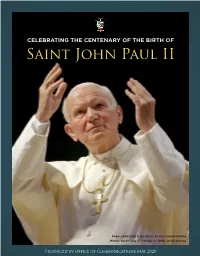

Saint John Paul II

CELEBRATING THE CENTENARY OF THE BIRTH OF Saint John Paul II Pope John Paul II gestures to the crowd during World Youth Day in Denver in 1993. (CNS photo) Produced by Office of Communications May 2020 On April 2, 2020 we commemorated the 15th Anniversary of St. John Paul II’s death and on May 18, 2020, we celebrate the Centenary of his birth. Many of us have special personal We remember his social justice memories of the impact of St. John encyclicals Laborem exercens (1981), Paul II’s ecclesial missionary mysticism Sollicitudo rei socialis (1987) and which was forged in the constant Centesimus annus (1991) that explored crises he faced throughout his life. the rich history and contemporary He planted the Cross of Jesus Christ relevance of Catholic social justice at the heart of every personal and teaching. world crisis he faced. During these We remember his emphasis on the days of COVID-19, we call on his relationship between objective truth powerful intercession. and history. He saw first hand in Nazism We vividly recall his visits to Poland, and Stalinism the bitter and tragic BISHOP visits during which millions of Poles JOHN O. BARRES consequences in history of warped joined in chants of “we want God,” is the fifth bishop of the culture of death philosophies. visits that set in motion the 1989 Catholic Diocese of Rockville In contrast, he asked us to be collapse of the Berlin Wall and a Centre. Follow him on witnesses to the Splendor of Truth, fundamental change in the world. Twitter, @BishopBarres a Truth that, if followed and lived We remember too, his canonization courageously, could lead the world of Saint Faustina, the spreading of global devotion to bright new horizons of charity, holiness and to the Divine Mercy and the establishment of mission. -

Topical Index

298 The Moral Life in Christ Index Page numbers in color indicate illustrations. Titles of paintings will be found under the name of the artist, unless they are anonymous. References to specific citations from Scripture and the Catechism will be found in the separate INDEX OF CITATIONS. A art and music in Church, 130 sanctifying grace in, 33, 34, atheism, 119, 124 235, 250–252, 287, 288 attractiveness. See sexuality Barzotti, Biagio, Pope abortion and abortion laws, Leo XIII with Cardinals St. Augustine of Hippo 50, 82, 88, 90–91, 103 Rampolla, Parochi, on Baptism, 43 Abraham, 103 Bonaparte, and Sacconi (ca. Benedict XVI on, 14 absolution, 148, 286 1890), 114 Champaigne, Philippe de, abstinence, 99, 175, 286 Baudricourt, Robert, 239 Saint Augustine (ca. 1650), Baumgartner, Johan acedia, 66, 286 212 Wolfgang, The Prodigal Son actual grace, 235, 286 Confessions, 12 Wasting his Inheritance (1724- Adam and Eve on Eternal Law, 58–59 1761), 6 marriage and, 108 on freedom, 9 beatitude, 34, 120, 193. See Original Justice and, 19 on grace, 246 also holiness Original Sin and, 17–22, 24, on happiness, 47 Beatitudes, 145, 147–150, 26, 33, 206, 293 152–154, 161, 165, 286 life of, 7 adoration, 275, 277, 286 Benedict XVI (pope) on love, 89 adulation, 129, 130, 286 Caritas in Veritate (papal passions and, 212 adultery, 93, 94, 102, 286 encyclical, 2009), 117–118 on prayer, 283 alcohol and drugs, 84, 141 Deus Caritas Est (papal Retractationes, 28 encyclical, 2005), 13–14 almsgiving, 123, 257, 286 On the Sermon on the general audience, Nov. -

The Use of Philosophical Principles in Catholic Social Thought: the Case of Gaudium Et Spes

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 45 Number 2 Volume 45, 2006, Number 2 Article 6 The Use of Philosophical Principles in Catholic Social Thought: The Case of Gaudium et Spes Rev. Joseph W. Koterski, S.J. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls Part of the Catholic Studies Commons This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE USE OF PHILOSOPHICAL PRINCIPLES IN CATHOLIC SOCIAL THOUGHT: THE CASE OF GAUDIUM ET SPES REVEREND JOSEPH W. KOTERSKI, S.J.t It is common to find individuals who are very attracted to questions of social justice and others quite uninterested, or even suspicious.1 At both extremes there are dangers to avoid. On the one hand, Catholicism may never be reduced to the concerns of "the social gospel" apart from the rest of the faith.2 On the other hand, the Church's social teachings, especially in the clear articulation given by recent popes and the Second Vatican Council, are not peripheral to the faith, not something purely optional, as if the essence of Catholicism were a matter of spirituality to the exclusion of morality.3 Like the rest of Catholic moral theology, Catholic Social Teaching (CST) has roots both in revelation and reason,4 and anyone interested in t Rev. Joseph W. -

Pastoral Letter on the Reading of Amoris Laetitia In

PASTORAL LETTER ON THE READING OF AMORIS LAETITIA IN LIGHT OF CHURCH TEACHING “A TRUE AND LIVING ICON” OF THE ARCHBISHOP OF PORTLAND, OREGON MOST REVEREND ALEXANDER K. SAMPLE TO THE PRIESTS, DEACONS, RELIGIOUS AND FAITHFUL OF THE ARCHDIOCESE “The couple that loves and begets life is a true, living icon … capable of revealing God the Creator and Savior.”1 With these words our Holy Father, Pope Francis, reminds us that married love is “a symbol of God’s inner life,” for the “triune God is a communion of love, and the family is its living reflection.”2 Of its very nature, marriage exists for the communion of life and love between spouses, ordered to the procreation and care of children, in an exclusive and permanent bond between one man and one woman. In this natural bond, existing even between unbaptized spouses, we are given “an image for understanding and describing the mystery of God himself.…”3 Christ our Lord elevated the natural bond of marriage to the dignity of a sacrament whereby the union of man and woman signifies the “union of Christ and the Church.”4 God, who is eternal and unchanging, gives marriage as a natural icon of himself; Christ elevates marriage into a sacrament signifying the permanent, indissoluble covenant with his people. Because the family is essential to the well-being of the world, the Church, and the spread of the Gospel, the world’s bishops gathered in the Synods of 2014 and 2015 to identify the real situation of marriages and families in the world today and to seek pastoral solutions for these challenges. -

John Paul II and the Law

Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy Volume 21 Article 7 Issue 1 Symposium on Pope John Paul II and the Law 1-1-2012 John Paul II: Migrant Pope Teaches on Unwritten Laws of Migration Nicholas DiMarzio Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp Recommended Citation Nicholas DiMarzio, John Paul II: Migrant Pope Teaches on Unwritten Laws of Migration, 21 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol'y 191 (2007). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol21/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN PAUL II: MIGRANT POPE TEACHES ON UNWRITTEN LAWS OF MIGRATION MOST REVEREND NICHOLAS DiMARzio, PH.D., D.D.* INTRODUCTION His Holiness, John Paul II, of happy memory, was one of the greatest teaching popes in the Church's history. He has given the Church a body of teaching that will take generations to fathom. This issue of the Notre DameJournal of Law, Ethics & Pub- lic Policy is an attempt to collate his teaching regarding law and public policy. This article will attempt to bring together John Paul II's thought and teaching on migration, which is implicit in many of his teachings, and also explicit in many of his discourses. Underlying his teaching is an understanding of human dignity which became the departure point forJohn Paul II's understand- ing of natural law. -

Humanae Vitae and Veritatis Splendor As Expositions of 'Natural Law'

Aemaet Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift für Philosophie und Theologie http://aemaet.de, ISSN 2195-173X Humanae Vitae and Veritatis Splendor as Expositions of ‘Natural Law’∗ Contrasted with Their Irrational Rejection Carlos A. Casanova∗∗ 2018 ∗This paper was written to be presented at the first meeting of the John Paul II Academy for Life and the Family, held in Rome on May 21st, the title of which was “Human Life, the Family and the Splendour of Truth: Gifts of God, Humanae vitae 50 years – Veritatis splendor 25 years.” The Text is available under the Creative Commons License Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) Publication date: 15.06.2018. ∗∗Carlos A. Casanova is a Catholic philosopher from Venezuela, who now lives in Chile. PhD in Philosophy by Universidad de Navarra (1995), he is currently Full Professor at Universidad Santo Tomás. Epost: carlosacasanovag@XYZ (replace ‘XYZ’ by ‘Gmail.com’) Mail: Ejército 146, Universidad Santo Tomás. Torre C, piso 7, Centro de Estudios Tomistas. Comuna de Santiago. Santiago Chile Aemaet Bd. 7, Nr. 1 (2018) 56-101, http://aemaet.de urn:nbn:de:0288-20130928720 Humanae Vitae and Veritatis Splendor 57 as Expositions of ‘Natural Law’ Abstract The paper holds that the encyclicals Humanae Vi- atae and Veritatis Splendor presuppose the West- ern and Christian view of morality as a science (natural or supernatural) which is able to uncover the real order of which human beings and their actions are a part. It shows how the theological dissidents who reject the main tenets of these en- cyclicals are unable to explain the moral order and, therefore, are less rational than the encyclicals and in lesser agreement with Revelation. -

Ii. Teologia W Perspektywie Ekumenii

II. TEOLOGIA W PERSPEKTYWIE EKUMENII Studia Oecumenica 15 (2015) s. 97–122 Sławomir NowoSad Wydział Teologii KUL Non-Catholic Reactions to Veritatis Splendor Abstract A growing ecumenical awareness among Christian theologians and ethicists has found in John Paul II’s moral encyclical Veritatis Splendor a fresh impetus for a development of common studies of moral issues. Not few mainly Protestant ethicists expressed their com- ments on the way the Pope discusses and defines fundamental problems of Christian moral teaching. Some of those comments were apparently positive, at times even enthusiastic (e.g. R. Benne, S. Hauerwas, O. O’Donovan, J.B. Elshtain), while others displayed a mixed reaction to the papal teaching (e.g. L.S. Mudge. G. Meilaender, M. Banner). There were also some authors who approached Veritatis Splendor critically, some even rejected it alto- gether (e.g. N.P. Harvey, R. Preston, H. Oppenheimer). Keywords: Veritatis splendor, moral theology/Christian ethics, ecumenical dialogue, Christian moral life. Niekatolickie reakcje na Veritatis Splendor Streszczenie Wraz z coraz głębszym zrozumieniem prawdy o tym, że „kto podziela jedną wiarę w Chrystusa, winien dzielić także jedno życie w Chrystusie” (ARCIC II, Life in Christ), tematyka moralna znajduje dla siebie coraz więcej miejsca w dialogu ekumenicznym. Zarazem chrześcijanie różnych tradycji mają coraz większą świadomość konieczności dawania wspólnego świadectwa wobec świata, także co do życia moralnego uczniów Chrystusa. Szczególnym źródłem dla ekumenicznych debat nad fundamentalnymi prob- lemami chrześcijańskiego nauczania moralnego stała się encyklika Jana Pawła II Veri- tatis splendor. Liczne grono etyków i teologów, głównie protestanckich (luterańskich, anglikańskich, metodystycznych i innych), dało wyraz swoim przekonaniom, odnosząc się do podstawowych bądź bardziej szczegółowych zagadnień, przedstawionych w tym doku- mencie. -

The Holy See

The Holy See ADDRESS OF JOHN PAUL II TO THE MEMBERS OF THE BISHOPS' CONFERENCE OF COLOMBIA ON THEIR "AD LIMINA" VISIT Thursday, 30 September 2004 Dear Brothers in the Episcopate, 1. I am pleased to receive you at this meeting which, at the end of your ad limina visit, enables me to greet you and to encourage you in hope, so necessary for the ministry that you generously carry out in your respective Archdioceses and Dioceses in the Ecclesiastical Provinces of Bogotá, Bucaramanga, Ibagué, Nueva Pamplona, Tunja and the recently erected Province of Villavicencio. With the pilgrimage to the tombs of the Apostles Peter and Paul, you have had the opportunity to strengthen the bonds that unite your tasks today with the mission that Christ entrusted to the Twelve and to find inspiration in his example of self-denial and constant devotion to the evangelization of all peoples. At this meeting and at others with the various offices of the Roman Curia, communion with the See of Peter and the concern that all Bishops must have for the universal Church becomes obvious and effective (cf. Lumen Gentium, n. 23). I am grateful to Cardinal Pedro Rubiano Sáenz for his words on behalf of all of you, expressing your attachment and sincere affection. In this way you also reflect on the profound religious spirit of the Colombian People and the great appreciation of your communities for the Pope. Take them my greeting and remind them that I keep them very present in my prayers, especially at this difficult time for the Nation. -

Pope Francis' Apostolic Constitution “Veritatis Gaudium”

N. 180129c Monday 29.01.2018 Pope Francis’ Apostolic Constitution “Veritatis gaudium” on ecclesiastical Universities and Faculties FRANCIS APOSTOLIC CONSTITUTION VERITATIS GAUDIUM ON ECCLESIASTICAL UNIVERSITIES AND FACULTIES FOREWORD 1.The joy of truth (Veritatis Gaudium) expresses the restlessness of the human heart until it encounters and dwells within God’s Light, and shares that Light with all people.[1] For truth is not an abstract idea, but is Jesus himself, the Word of God in whom is the Life that is the Light of man (cf. Jn 1:4), the Son of God who is also the Son of Man. He alone, “in revealing the mystery of the Father and of his love, fully reveals humanity to itself and brings to light its very high calling”.[2] When we encounter the Living One (cf. Rev 1:18) and the firstborn among many brothers (cf. Rom 8:29), our hearts experience, even now, amid the vicissitudes of history, the unfading light and joy born of our union with God and our unity with our brothers and sisters in the common home of creation. One day we will experience that endless joy in full communion with God. In Jesus’ prayer to the Father – “that they may all be one; even as you, Father, are in me, and I in you, that they also may be in us” (Jn 17:21) – we find the secret of the joy that Jesus wishes to share in its fullness (cf. Jn 15:11). It is the joy that comes from the Father through the gift of the Holy Spirit, who is the Spirit of truth and of love, freedom, justice and unity. -

Foundational Catechetical Documents

Foundational Catechetical Documents Religion curriculum and instruction are governed by and conform to the principles, declarations, and norms presented in official Church documents. Opportunities ought to be provided for religion teachers, campus ministers, and school administrators to read, understand and discuss these documents and their essential content. Lumen Gentium, Vatican II (1964) General Catechetical Directory, Congregation for the Clergy (1971) To Teach as Jesus Did: A Pastoral Message on Catholic Education, USCCB (1972) Sharing the Light of Faith: National Catechetical Directory, USCCB (1979) Catechesi Tradendae (On Catechesis in Our Time), John Paul II (1979) Lay Catholics in Schools: Witnesses to Faith, Congregation for Catholic Education (1982) The Religious Dimension of Education in a Catholic School, Congregation for Catholic Education (1988) Guidelines for Doctrinally Sound Catechetical Materials, USCCB (1990) The Catechism of the Catholic Church, Holy See (1992) General Directory for Catechesis, Congregation for the Clergy (1997) Fides et Ratio (On the Relationship between Faith and Reason), John Paul II (1998) Ecclesia in America, John Paul II (1999) Our Hearts Were Burning Within Us, USCCB (1999) Gathered and Sent: Synod Initiatives, Archdiocese of Los Angeles (2003) National Directory for Catechesis, USCCB (2005) Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace (2005) Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Holy See (2006) United States Catholic Catechism for Adults, USCCB (2006) Doctrinal Elements of a Curriculum Framework, USCCB (2008) Guidelines for Obtaining The California Catechist Certificate and The California Master Catechist Certificate, CCC (2009) Christian morality consists, in the simplicity of the Gospel, in following Jesus Christ, in abandoning oneself to him, in letting oneself be transformed by his grace and renewed by his mercy, gifts which come to us in the living communion of his Church.