Pope John Paul Ii, Freedom, and Constitutional Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Idea of the Common Good in the Light of Encyclicals Laborem Exercens and Centesimus Annus

Teka Komisji Prawniczej PAN Oddział w Lublinie, t. XIII, 2020, nr 1, s. 479-491 https://doi.org/10.32084/tekapr.2020.13.1-36 THE IDEA OF THE COMMON GOOD IN THE LIGHT OF ENCYCLICALS LABOREM EXERCENS AND CENTESIMUS ANNUS Rev. Wojciech Wojtyła, Ph.D. Department of Legal Theory and History, Faculty of Law and Administration at the Kazimierz Pułaski University of Technology and Humanities in Radom e-mail: [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5482-705X Summary. John Paul II placed man at the centre of his reflection in the encyclicals Laborem exer- cens and Centesimus annus and it was in man, his intelligence and competences, his capacity for creative initiative and entrepreneurship, that the pope saw the mainspring of social wealth and good. The deliberations in both the papal documents are founded on the idea it is not material capital but science, technology, and skills, referred to as new types of property, that are the greatest asset of industrial countries at present. In John Paul II’s belief, a correctly interpreted relationship between economy, anthropology, and ethics is the key to overcoming social problems, with various forms of alienation being the gravest. A vision of man as a creative subject whose ability of personal parti- cipation is the basic common good of every society plays a special role in giving the right shape to organized social life. The pope argued a personalistic understanding of common good both relieves tensions between private property and the right to the universal destination of goods as defined by the Catholic social philosophy and paves the way for economic success of nations and states. -

Method in American Catholic Moral Eology a Er Veritatis Splendor

Journal of Moral eology, Vol. 1, No. 1 (2012): 170-192 REVIEW ESSAY Method in American Catholic Moral eology Aer Veritatis Splendor DAVID CLOUTIER and WILLIAM C. MATTISON III UR PURPOSE in this inaugural issue of the Journal of Moral eology is to reflect on the state of“ method” in Catholic moral theology today. But rather than present a set of essays, each representing a different method or “Oschool,” we chose to invite authors at institutions training American Catholic moral theologians to write essays reflecting on the influence of a diverse set of thinkers, thinkers who both immediately preceded and particularly influenced American Catholic moral theology today. We hope that presenting a set of essays by these current shapers of American Catholic moral theologians, about recent influential fig- ures, will provide a lens into what characterizes Catholic moral the- ology today. So, does this decision about how to reflect on methodology reveal that American Catholic moral theology today in fact has no “meth- od”? Certainly as compared with pre-Vatican II Catholic theology of all subdisciplines, which Gerard McCool describes as marked by a “search for a unitary method,”1 moral theology today does not pre- sent a straightforward unified methodology. Yet to say “there is no method” says too little. Such a claim could wrongly suggest that there 1 Gerard McCool, Nineteenth Century Scholasticism: e Search for a Unitary Meth- od (New York: Fordham University Press, 1989). Method in American Catholic Moral eology 171 are no identifiable parameters in the discipline of Catholic moral theology today. It could also fan the flames of a reactionary trend seeking refuge in the perceived order of pre-Vatican II moral theolo- gy, a move that, moreover, has no real support in the work of Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI. -

John Paul II and Children's Education Christopher Tollefsen

Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy Volume 21 Article 6 Issue 1 Symposium on Pope John Paul II and the Law 1-1-2012 John Paul II and Children's Education Christopher Tollefsen Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp Recommended Citation Christopher Tollefsen, John Paul II and Children's Education, 21 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol'y 159 (2007). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol21/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN PAUL H AND CHILDREN'S EDUCATION CHRISTOPHER TOLLEFSEN* Like many other moral and social issues, children's educa- tion can serve as a prism through which to understand the impli- cations of moral, political, and legal theory. Education, like the family, abortion, and embryonic research, capital punishment, euthanasia, and other issues, raises a number of questions, the answers to which are illustrative of a variety of moral, political, religious, and legal standpoints. So, for example, a libertarian, a political liberal, and a per- fectionist natural lawyer will all have something to say about the question of who should provide a child's education, what the content of that education should be, and what mechanisms for the provision of education, such as school vouchers, will or will not be morally and politically permissible. -

The Holy See

The Holy See IOANNES PAULUS PP. II EVANGELIUM VITAE To the Bishops Priests and Deacons Men and Women religious lay Faithful and all People of Good Will on the Value and Inviolability of Human Life INTRODUCTION 1. The Gospel of life is at the heart of Jesus' message. Lovingly received day after day by the Church, it is to be preached with dauntless fidelity as "good news" to the people of every age and culture. At the dawn of salvation, it is the Birth of a Child which is proclaimed as joyful news: "I bring you good news of a great joy which will come to all the people; for to you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, who is Christ the Lord" (Lk 2:10-11). The source of this "great joy" is the Birth of the Saviour; but Christmas also reveals the full meaning of every human birth, and the joy which accompanies the Birth of the Messiah is thus seen to be the foundation and fulfilment of joy at every child born into the world (cf. Jn 16:21). When he presents the heart of his redemptive mission, Jesus says: "I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly" (Jn 10:10). In truth, he is referring to that "new" and "eternal" life 2 which consists in communion with the Father, to which every person is freely called in the Son by the power of the Sanctifying Spirit. It is precisely in this "life" that all the aspects and stages of human life achieve their full significance. -

Spring 2020 Booklist Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family

Spring 2020 Booklist Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family JPI 510/729 Theological Anthropology McCarthy • Compendium of readings (available through Cognella) • Burns, J., Ed. Theological Anthropology. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1981. • Balthasar, Hans Urs. The Christian State of Life. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1983. • ______. Theo-Drama II, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1990. ISBN 0898702879 • ______. Theo-Drama III. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 11992. ISBN 089870295X. • De Lubac, H. The Drama of Atheist Humanism. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1995. ISBN: 089870443X • De Lubac, H. A Brief Catechesis on Nature and Grace. Ignatius Press, 1984. ISBN: 0898700353 • John Paul II. Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body. Pauline, 1997. • Schmitz, K. The Gift: Creation. Marquette University Press, Milwaukee, 1982. • Scola. The Nuptial Mystery. Trans. M. Borras. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans, 2005. • Spaemann, R. Essays in Anthropology – Variations on a Theme. Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books, 2010. JPI 532/707 Biblical Theology of Marriage and Family (OT) Atkinson • Holy Scriptures [The most recent edition of Ignatius Press’ RSV is particularly good.] • Biblical and Theological Foundation of the Family, Joseph Atkinson (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2014). • Jean-Baptiste Edart (with Himbaza and Schenker). The Bible on the Question of Homosexuality. (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2012). JPI 550/850 Gender and the Sexual Difference D.L. Schindler • Compendium of readings (available through Cognella) • Simon Baron-Cohen, The Essential Difference. (New York: Basic Books, 2003). • John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them: Theology of the Body. • Eve Tushnet, Gay and Catholic (Ave Maria Press, 2014). -

The Holy See

The Holy See MESSAGE OF THE HOLY FATHER ON THE OCCASION OF THE 14TH WORLD YOUTH DAY “The Father loves you” (cf. Jn 16:27) Dear young friends! 1. In the perspective of the Jubilee which is now drawing near, 1999 is aimed at “broadening the horizons of believers so that they will see things in the perspective of Christ: in the perspective of the 'Father who is in heaven' from whom the Lord was sent and to whom he has returned” (Tertio Millennio Adveniente, 49). It is, indeed, not possible to celebrate Christ and his jubilee without turning, with him, towards God, his Father and our Father (cf. Jn 20:17). The Holy Spirit also takes us back to the Father and to Jesus. If the Spirit teaches us to say: “Jesus is Lord” (cf. 1Cor 12:3), it is to make us capable of speaking with God, calling him “Abba! Father!” (cf. Gal 4:6). I invite you also, together with the whole Church, to turn towards God the Father and to listen with gratitude and wonder to the amazing revelation of Jesus: “The Father loves you!” (cf. Jn 16:27). These are the words I entrust to you as theme for the XIV World Youth Day. Dear young people, receive the love that God first gives you (cf. 1Jn 4:19). Hold fast to this certainty, the only one that can give meaning, strength and joy to life: his love will never leave you, his covenant of peace will never be removed from you (cf. Is 54:10). -

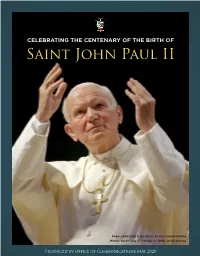

Saint John Paul II

CELEBRATING THE CENTENARY OF THE BIRTH OF Saint John Paul II Pope John Paul II gestures to the crowd during World Youth Day in Denver in 1993. (CNS photo) Produced by Office of Communications May 2020 On April 2, 2020 we commemorated the 15th Anniversary of St. John Paul II’s death and on May 18, 2020, we celebrate the Centenary of his birth. Many of us have special personal We remember his social justice memories of the impact of St. John encyclicals Laborem exercens (1981), Paul II’s ecclesial missionary mysticism Sollicitudo rei socialis (1987) and which was forged in the constant Centesimus annus (1991) that explored crises he faced throughout his life. the rich history and contemporary He planted the Cross of Jesus Christ relevance of Catholic social justice at the heart of every personal and teaching. world crisis he faced. During these We remember his emphasis on the days of COVID-19, we call on his relationship between objective truth powerful intercession. and history. He saw first hand in Nazism We vividly recall his visits to Poland, and Stalinism the bitter and tragic BISHOP visits during which millions of Poles JOHN O. BARRES consequences in history of warped joined in chants of “we want God,” is the fifth bishop of the culture of death philosophies. visits that set in motion the 1989 Catholic Diocese of Rockville In contrast, he asked us to be collapse of the Berlin Wall and a Centre. Follow him on witnesses to the Splendor of Truth, fundamental change in the world. Twitter, @BishopBarres a Truth that, if followed and lived We remember too, his canonization courageously, could lead the world of Saint Faustina, the spreading of global devotion to bright new horizons of charity, holiness and to the Divine Mercy and the establishment of mission. -

Download Download

Implementing the Principles of the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Catholic Church in Catholic Higher Education1 His Eminence Renato Raffaele Cardinal Martino The purpose of this discussion is to share a refl ection on the imple- mentation of Catholic Social Teaching (CST) in the ministry of Catholic higher education. In particular, I wish to highlight the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church2 that was completed by the Pontifi cal Council for Justice and Peace at the request of the Servant of God, Pope John Paul II. Designed to be a user-friendly synthesis of the principles of CST, the Compendium has proven to be an extremely practical and substantial resource. It has now been translated into 40 different lan- guages and is widely available throughout the world. In a certain sense, the Social Doctrine of the Catholic Church has been called “the Church’s best kept secret.” Why is this the case? Before the publication of the Compendium, perhaps because the social teach- ings of the popes were responding to specifi c situations (such as the cir- cumstances of the workers at the end of nineteenth century examined by Pope Leo XIII in his Encyclical Rerum novarum3), a well-structured exposition of the social doctrine of the Church did not exist. It was not until 1999 that Pope John Paul II, in his exhortation Ecclesia in America4, promised a document that would synthesize the social doc- trine of the Church. He then asked the Pontifi cal Council for Justice and Peace to prepare such a document—the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church—which was fi rst released on October 25, 2004. -

The Church in the Modern World: Papal Leadership, Lay Response

The Church in the Modern World: Papal Leadership, Lay Response How are we to live our Christianity in today’s world? Vatican Council II named us, the laity, as the ones whose task it is to change the world. How do we do that? From the 1800s our Popes have been showing us how. Join in our Singing Praise study of what our Holy Fathers (and Vatican Council II) have said to guide us. After an initial review of Catholic teaching on Divine Revelation, the call of the laity, and the Vatican Council II document, “The Church in the Modern World,” we will see what popes have said about how to change the world we live in. This study may challenge our thinking, but the reading will be simple. Each week there will be a one page summary of Church teaching and three pages of quotations from popes and church documents. This is a discussion study of main ideas and their application, though there will be links to original documents for those who may want to read more. September 10: How Do We Know Something Is of God? A Look at Catholic teaching on Divine Revelation and the Hierarchy of Truths—from Vatican Council II and the Catholic Catechism. September 17: Patriotic Rosary, no class. September 24: What is the Role of Church in our Modern World? A look at how the Church’s Role is defined in the Vatican Council II document, Gaudium et Spes. October 1: In the Big Picture, What am I, Ordinary Lay Catholic, to Do? A look at Vatican II documents and words of Popes St. -

Topical Index

298 The Moral Life in Christ Index Page numbers in color indicate illustrations. Titles of paintings will be found under the name of the artist, unless they are anonymous. References to specific citations from Scripture and the Catechism will be found in the separate INDEX OF CITATIONS. A art and music in Church, 130 sanctifying grace in, 33, 34, atheism, 119, 124 235, 250–252, 287, 288 attractiveness. See sexuality Barzotti, Biagio, Pope abortion and abortion laws, Leo XIII with Cardinals St. Augustine of Hippo 50, 82, 88, 90–91, 103 Rampolla, Parochi, on Baptism, 43 Abraham, 103 Bonaparte, and Sacconi (ca. Benedict XVI on, 14 absolution, 148, 286 1890), 114 Champaigne, Philippe de, abstinence, 99, 175, 286 Baudricourt, Robert, 239 Saint Augustine (ca. 1650), Baumgartner, Johan acedia, 66, 286 212 Wolfgang, The Prodigal Son actual grace, 235, 286 Confessions, 12 Wasting his Inheritance (1724- Adam and Eve on Eternal Law, 58–59 1761), 6 marriage and, 108 on freedom, 9 beatitude, 34, 120, 193. See Original Justice and, 19 on grace, 246 also holiness Original Sin and, 17–22, 24, on happiness, 47 Beatitudes, 145, 147–150, 26, 33, 206, 293 152–154, 161, 165, 286 life of, 7 adoration, 275, 277, 286 Benedict XVI (pope) on love, 89 adulation, 129, 130, 286 Caritas in Veritate (papal passions and, 212 adultery, 93, 94, 102, 286 encyclical, 2009), 117–118 on prayer, 283 alcohol and drugs, 84, 141 Deus Caritas Est (papal Retractationes, 28 encyclical, 2005), 13–14 almsgiving, 123, 257, 286 On the Sermon on the general audience, Nov. -

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas Thomas Aquinas: Teacher of Humanity Edited by John P. Hittinger and Daniel C. Wagner Proceedings from the First Conference of the Pontifical Academy of St. Thomas Aquinas held in the United States of America Thomas Aquinas: Teacher of Humanity Edited by John P. Hittinger and Daniel C. Wagner This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by John P. Hittinger, Daniel C. Wagner and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7554-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7554-7 DEDICATION TO THE MEMORY OF REV. VICTOR BREZIK, C.S.B. 1913-2009 TEXAN—BASILIAN—THOMIST Father Victor Brezik, who joined the University of St. Thomas faculty in 1954, adopted as his personal motto, “Dare to do whatever you can,” from his favorite philosopher, St. Thomas Aquinas. Fr. Brezik’s philosophical attitude and vision inspired generations of students and colleagues. In addition to his many contributions to the University, Fr. Brezik co-founded with Hugh Roy Marshall the University of St. Thomas’ Center for Thomistic Studies in 1975. The Center for Thomistic Studies, where the wisdom of Thomas Aquinas could be brought to bear on the problems of the contemporary world, was Fr. -

Centesimus Annus and the Renewal of Culture* Rev. Avery Dulles, S.J

Journal of Markets & Morality 2, no. 1(Spring 1999), 1-7 Copyright © 1999 Center for Economic Personalism Centesimus Annus and the Renewal of Culture* Rev. Avery Dulles, S.J. Professor of Theology Fordham University “The individual today is often suffocated between the two poles represented by the state and the marketplace. At times it seems that he exists only as a producer and consumer of goods or as an object of state administration.”1 In these words from Centesimus Annus, Pope John Paul II presents the fundamen- tal problem of which I propose to speak in this brief essay. Western society in the present century has been fluctuating between the two extremes mentioned by the Holy Father. In the United States we seem to be caught between the seductions of the welfare state and libertarian capital- ism. The one, consistently pursued, leads to the “animal farm” of state social- ism; the other, to the anarchic jungle of social Darwinism. To transcend the dilemma, it is necessary to recognize that politicization and commercialization are not the only alternatives. In a recent speech, Mary Ann Glendon pointed to the necessity of getting beyond the market/state di- chotomy. “There’s a growing recognition,” she said, “that human beings do not flourish if the conditions under which we work and raise our families are entirely subject either to the play of market forces or to the will of distant bureaucrats. The search is on for practical alternatives to hardhearted laissez- faire on the one hand and ham-fisted top-down regulation on the other.”2 The first step in this search, I suggest, is to acknowledge that in addition to the political and the economic orders there is a third, more fundamental than either.