John Paul II and Children's Education Christopher Tollefsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscapes of Korean and Korean American Biblical Interpretation

BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION AMERICAN AND KOREAN LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN International Voices in Biblical Studies In this first of its kind collection of Korean and Korean American Landscapes of Korean biblical interpretation, essays by established and emerging scholars reflect a range of historical, textual, feminist, sociological, theological, and postcolonial readings. Contributors draw upon ancient contexts and Korean American and even recent events in South Korea to shed light on familiar passages such as King Manasseh read through the Sewol Ferry Tragedy, David and Bathsheba’s narrative as the backdrop to the prohibition against Biblical Interpretation adultery, rereading the virtuous women in Proverbs 31:10–31 through a Korean woman’s experience, visualizing the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and demarcations in Galatians, and introducing the extrabiblical story of Eve and Norea, her daughter, through story (re)telling. This volume of essays introduces Korean and Korean American biblical interpretation to scholars and students interested in both traditional and contemporary contextual interpretations. Exile as Forced Migration JOHN AHN is AssociateThe Prophets Professor Speak of Hebrew on Forced Bible Migration at Howard University ThusSchool Says of Divinity.the LORD: He Essays is the on author the Former of and Latter Prophets in (2010) Honor ofand Robert coeditor R. Wilson of (2015) and (2009). Ahn Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-379-6) available at http://ivbs.sbl-site.org/home.aspx Edited by John Ahn LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION INTERNATIONAL VOICES IN BIBLICAL STUDIES Jione Havea Jin Young Choi Musa W. Dube David Joy Nasili Vaka’uta Gerald O. West Number 10 LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION Edited by John Ahn Atlanta Copyright © 2019 by SBL Press All rights reserved. -

The Idea of the Common Good in the Light of Encyclicals Laborem Exercens and Centesimus Annus

Teka Komisji Prawniczej PAN Oddział w Lublinie, t. XIII, 2020, nr 1, s. 479-491 https://doi.org/10.32084/tekapr.2020.13.1-36 THE IDEA OF THE COMMON GOOD IN THE LIGHT OF ENCYCLICALS LABOREM EXERCENS AND CENTESIMUS ANNUS Rev. Wojciech Wojtyła, Ph.D. Department of Legal Theory and History, Faculty of Law and Administration at the Kazimierz Pułaski University of Technology and Humanities in Radom e-mail: [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5482-705X Summary. John Paul II placed man at the centre of his reflection in the encyclicals Laborem exer- cens and Centesimus annus and it was in man, his intelligence and competences, his capacity for creative initiative and entrepreneurship, that the pope saw the mainspring of social wealth and good. The deliberations in both the papal documents are founded on the idea it is not material capital but science, technology, and skills, referred to as new types of property, that are the greatest asset of industrial countries at present. In John Paul II’s belief, a correctly interpreted relationship between economy, anthropology, and ethics is the key to overcoming social problems, with various forms of alienation being the gravest. A vision of man as a creative subject whose ability of personal parti- cipation is the basic common good of every society plays a special role in giving the right shape to organized social life. The pope argued a personalistic understanding of common good both relieves tensions between private property and the right to the universal destination of goods as defined by the Catholic social philosophy and paves the way for economic success of nations and states. -

The Holy See

The Holy See IOANNES PAULUS PP. II EVANGELIUM VITAE To the Bishops Priests and Deacons Men and Women religious lay Faithful and all People of Good Will on the Value and Inviolability of Human Life INTRODUCTION 1. The Gospel of life is at the heart of Jesus' message. Lovingly received day after day by the Church, it is to be preached with dauntless fidelity as "good news" to the people of every age and culture. At the dawn of salvation, it is the Birth of a Child which is proclaimed as joyful news: "I bring you good news of a great joy which will come to all the people; for to you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, who is Christ the Lord" (Lk 2:10-11). The source of this "great joy" is the Birth of the Saviour; but Christmas also reveals the full meaning of every human birth, and the joy which accompanies the Birth of the Messiah is thus seen to be the foundation and fulfilment of joy at every child born into the world (cf. Jn 16:21). When he presents the heart of his redemptive mission, Jesus says: "I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly" (Jn 10:10). In truth, he is referring to that "new" and "eternal" life 2 which consists in communion with the Father, to which every person is freely called in the Son by the power of the Sanctifying Spirit. It is precisely in this "life" that all the aspects and stages of human life achieve their full significance. -

Gerard Mannion Is to Be Congratulated for This Splendid Collection on the Papacy of John Paul II

“Gerard Mannion is to be congratulated for this splendid collection on the papacy of John Paul II. Well-focused and insightful essays help us to understand his thoughts on philosophy, the papacy, women, the church, religious life, morality, collegiality, interreligious dialogue, and liberation theology. With authors representing a wide variety of perspectives, Mannion avoids the predictable ideological battles over the legacy of Pope John Paul; rather he captures the depth and complexity of this extraordinary figure by the balance, intelligence, and comprehensiveness of the volume. A well-planned and beautifully executed project!” —James F. Keenan, SJ Founders Professor in Theology Boston College Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts “Scenes of the charismatic John Paul II kissing the tarmac, praying with global religious leaders, addressing throngs of adoring young people, and finally dying linger in the world’s imagination. This book turns to another side of this outsized religious leader and examines his vision of the church and his theological positions. Each of these finely tuned essays show the greatness of this man by replacing the mythological account with the historical record. The straightforward, honest, expert, and yet accessible analyses situate John Paul II in his context and show both the triumphs and the ambiguities of his intellectual legacy. This masterful collection is absolutely basic reading for critically appreciating the papacy of John Paul II.” —Roger Haight, SJ Union Theological Seminary New York “The length of John Paul II’s tenure of the papacy, the complexity of his personality, and the ambivalence of his legacy make him not only a compelling subject of study, but also a challenging one. -

![Vincentiana Vol. 49, No. 2 [Full Issue]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8427/vincentiana-vol-49-no-2-full-issue-778427.webp)

Vincentiana Vol. 49, No. 2 [Full Issue]

Vincentiana Volume 49 Number 2 Vol. 49, No. 2 Article 1 2005 Vincentiana Vol. 49, No. 2 [Full Issue] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation (2005) "Vincentiana Vol. 49, No. 2 [Full Issue]," Vincentiana: Vol. 49 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol49/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Via Sapientiae: The Institutional Repository at DePaul University Vincentiana (English) Vincentiana 4-30-2005 Volume 49, no. 2: March-April 2005 Congregation of the Mission Recommended Citation Congregation of the Mission. Vincentiana, 49, no. 2 (March-April 2005) This Journal Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentiana at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana (English) by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VINCENTIANA 49" YEAR-N.2 MARCH-APRII. 2005 Vincentian Ongoing Formation CONGREGATION OF TIIF. MISSION GFNERAI CURIA VINCENTIANA Magazine of the Congregation of the Mission published every two months Holy See 1 1 i holy Father in the Father's (louse 49' Year - N. 2 11.4 Appointment March-April 2005 11-1 Ilabenius Papam! Editor Alfredo Becerro Vazquez, C.M. -

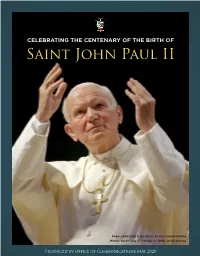

Saint John Paul II

CELEBRATING THE CENTENARY OF THE BIRTH OF Saint John Paul II Pope John Paul II gestures to the crowd during World Youth Day in Denver in 1993. (CNS photo) Produced by Office of Communications May 2020 On April 2, 2020 we commemorated the 15th Anniversary of St. John Paul II’s death and on May 18, 2020, we celebrate the Centenary of his birth. Many of us have special personal We remember his social justice memories of the impact of St. John encyclicals Laborem exercens (1981), Paul II’s ecclesial missionary mysticism Sollicitudo rei socialis (1987) and which was forged in the constant Centesimus annus (1991) that explored crises he faced throughout his life. the rich history and contemporary He planted the Cross of Jesus Christ relevance of Catholic social justice at the heart of every personal and teaching. world crisis he faced. During these We remember his emphasis on the days of COVID-19, we call on his relationship between objective truth powerful intercession. and history. He saw first hand in Nazism We vividly recall his visits to Poland, and Stalinism the bitter and tragic BISHOP visits during which millions of Poles JOHN O. BARRES consequences in history of warped joined in chants of “we want God,” is the fifth bishop of the culture of death philosophies. visits that set in motion the 1989 Catholic Diocese of Rockville In contrast, he asked us to be collapse of the Berlin Wall and a Centre. Follow him on witnesses to the Splendor of Truth, fundamental change in the world. Twitter, @BishopBarres a Truth that, if followed and lived We remember too, his canonization courageously, could lead the world of Saint Faustina, the spreading of global devotion to bright new horizons of charity, holiness and to the Divine Mercy and the establishment of mission. -

The Church in the Modern World: Papal Leadership, Lay Response

The Church in the Modern World: Papal Leadership, Lay Response How are we to live our Christianity in today’s world? Vatican Council II named us, the laity, as the ones whose task it is to change the world. How do we do that? From the 1800s our Popes have been showing us how. Join in our Singing Praise study of what our Holy Fathers (and Vatican Council II) have said to guide us. After an initial review of Catholic teaching on Divine Revelation, the call of the laity, and the Vatican Council II document, “The Church in the Modern World,” we will see what popes have said about how to change the world we live in. This study may challenge our thinking, but the reading will be simple. Each week there will be a one page summary of Church teaching and three pages of quotations from popes and church documents. This is a discussion study of main ideas and their application, though there will be links to original documents for those who may want to read more. September 10: How Do We Know Something Is of God? A Look at Catholic teaching on Divine Revelation and the Hierarchy of Truths—from Vatican Council II and the Catholic Catechism. September 17: Patriotic Rosary, no class. September 24: What is the Role of Church in our Modern World? A look at how the Church’s Role is defined in the Vatican Council II document, Gaudium et Spes. October 1: In the Big Picture, What am I, Ordinary Lay Catholic, to Do? A look at Vatican II documents and words of Popes St. -

Topical Index

298 The Moral Life in Christ Index Page numbers in color indicate illustrations. Titles of paintings will be found under the name of the artist, unless they are anonymous. References to specific citations from Scripture and the Catechism will be found in the separate INDEX OF CITATIONS. A art and music in Church, 130 sanctifying grace in, 33, 34, atheism, 119, 124 235, 250–252, 287, 288 attractiveness. See sexuality Barzotti, Biagio, Pope abortion and abortion laws, Leo XIII with Cardinals St. Augustine of Hippo 50, 82, 88, 90–91, 103 Rampolla, Parochi, on Baptism, 43 Abraham, 103 Bonaparte, and Sacconi (ca. Benedict XVI on, 14 absolution, 148, 286 1890), 114 Champaigne, Philippe de, abstinence, 99, 175, 286 Baudricourt, Robert, 239 Saint Augustine (ca. 1650), Baumgartner, Johan acedia, 66, 286 212 Wolfgang, The Prodigal Son actual grace, 235, 286 Confessions, 12 Wasting his Inheritance (1724- Adam and Eve on Eternal Law, 58–59 1761), 6 marriage and, 108 on freedom, 9 beatitude, 34, 120, 193. See Original Justice and, 19 on grace, 246 also holiness Original Sin and, 17–22, 24, on happiness, 47 Beatitudes, 145, 147–150, 26, 33, 206, 293 152–154, 161, 165, 286 life of, 7 adoration, 275, 277, 286 Benedict XVI (pope) on love, 89 adulation, 129, 130, 286 Caritas in Veritate (papal passions and, 212 adultery, 93, 94, 102, 286 encyclical, 2009), 117–118 on prayer, 283 alcohol and drugs, 84, 141 Deus Caritas Est (papal Retractationes, 28 encyclical, 2005), 13–14 almsgiving, 123, 257, 286 On the Sermon on the general audience, Nov. -

From Memory to Freedom Research on Polish Thinking About National Security and Political Community

Cezary Smuniewski From Memory to Freedom Research on Polish Thinking about National Security and Political Community Publication Series: Monographs of the Institute of Political Science Scientific Reviewers: Waldemar Kitler, War Studies Academy, Poland Agostino Massa, University of Genoa, Italy The study was performed under the 2017 Research and Financial Plan of War Studies Academy. Title of the project: “Bilateral implications of security sciences and reflection resulting from religious presumptions” (project no. II.1.1.0 grant no. 800). Translation: Małgorzata Mazurek Aidan Hoyle Editor: Tadeusz Borucki, University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland Typeseting: Manuscript Konrad Jajecznik © Copyright by Cezary Smuniewski, Warszawa 2018 © Copyright by Instytut Nauki o Polityce, Warszawa 2018 All rights reserved. Any reproduction or adaptation of this publication, in whole or any part thereof, in whatever form and by whatever media (typographic, photographic, electronic, etc.), is prohibited without the prior written consent of the Author and the Publisher. Size: 12,1 publisher’s sheets Publisher: Institute of Political Science Publishers www.inop.edu.pl ISBN: 978-83-950685-7-7 Printing and binding: Fabryka Druku Contents Introduction 9 1. Memory - the “beginning” of thinking about national security of Poland 15 1.1. Memory builds our political community 15 1.2. We learn about memory from the ancient Greeks and we experience it in a Christian way 21 1.3. Thanks to memory, we know who a human being is 25 1.4. From memory to wisdom 33 1.5. Conclusions 37 2. Identity – the “condition” for thinking about national security of Poland 39 2.1. Contemporary need for identity 40 2.2. -

Centesimus Annus and the Renewal of Culture* Rev. Avery Dulles, S.J

Journal of Markets & Morality 2, no. 1(Spring 1999), 1-7 Copyright © 1999 Center for Economic Personalism Centesimus Annus and the Renewal of Culture* Rev. Avery Dulles, S.J. Professor of Theology Fordham University “The individual today is often suffocated between the two poles represented by the state and the marketplace. At times it seems that he exists only as a producer and consumer of goods or as an object of state administration.”1 In these words from Centesimus Annus, Pope John Paul II presents the fundamen- tal problem of which I propose to speak in this brief essay. Western society in the present century has been fluctuating between the two extremes mentioned by the Holy Father. In the United States we seem to be caught between the seductions of the welfare state and libertarian capital- ism. The one, consistently pursued, leads to the “animal farm” of state social- ism; the other, to the anarchic jungle of social Darwinism. To transcend the dilemma, it is necessary to recognize that politicization and commercialization are not the only alternatives. In a recent speech, Mary Ann Glendon pointed to the necessity of getting beyond the market/state di- chotomy. “There’s a growing recognition,” she said, “that human beings do not flourish if the conditions under which we work and raise our families are entirely subject either to the play of market forces or to the will of distant bureaucrats. The search is on for practical alternatives to hardhearted laissez- faire on the one hand and ham-fisted top-down regulation on the other.”2 The first step in this search, I suggest, is to acknowledge that in addition to the political and the economic orders there is a third, more fundamental than either. -

The Use of Philosophical Principles in Catholic Social Thought: the Case of Gaudium Et Spes

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 45 Number 2 Volume 45, 2006, Number 2 Article 6 The Use of Philosophical Principles in Catholic Social Thought: The Case of Gaudium et Spes Rev. Joseph W. Koterski, S.J. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls Part of the Catholic Studies Commons This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE USE OF PHILOSOPHICAL PRINCIPLES IN CATHOLIC SOCIAL THOUGHT: THE CASE OF GAUDIUM ET SPES REVEREND JOSEPH W. KOTERSKI, S.J.t It is common to find individuals who are very attracted to questions of social justice and others quite uninterested, or even suspicious.1 At both extremes there are dangers to avoid. On the one hand, Catholicism may never be reduced to the concerns of "the social gospel" apart from the rest of the faith.2 On the other hand, the Church's social teachings, especially in the clear articulation given by recent popes and the Second Vatican Council, are not peripheral to the faith, not something purely optional, as if the essence of Catholicism were a matter of spirituality to the exclusion of morality.3 Like the rest of Catholic moral theology, Catholic Social Teaching (CST) has roots both in revelation and reason,4 and anyone interested in t Rev. Joseph W. -

177618331.Pdf

Christian Identity Studies in Reformed Theology Editor-in-chief Eduardus Van der Borght, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Editorial Board Abraham van de Beek, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Martien Brinkman, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Alasdair Heron, University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, emeritus Dirk van Keulen, Leiden University Daniel Migliore, Princeton Theological Seminary Richard Mouw, Fuller Theological Seminary, Pasadena Gerrit Singgih, Duta Wacana Christian University, Yogjakarta Conrad Wethmar, University of Pretoria VOLUME 16 Christian Identity Edited by Eduardus Van der Borght LEIDEN • BOSTON 2008 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data International Reformed Theological Institute. International Conference (6th : 2005 : Seoul, Korea) Christian identity / edited by Eduardus van der Borght. p. cm. -- (Studies in reformed theology ; v. 16) Includes index. ISBN 978-90-04-15806-1 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Identification (Religion)--Congresses. 2. Reformed Church–Doctrines--Congresses. I. Borght, Ed. A. J. G. van der, 1956- II. Title. III. Series. BV4509.5.I58 2005 261.2--dc22 2008018712 ISSN 1571-4799 ISBN 978 90 04 15806 1 Copyright 2008 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA.