From Memory to Freedom Research on Polish Thinking About National Security and Political Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Making Popular and Solidarity Economies in Dollarized Ecuador: Money, Law, and the Social After Neoliberalism Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3xx5n43g Author Nelms, Taylor Campbell Nahikian Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Making Popular and Solidarity Economies in Dollarized Ecuador: Money, Law, and the Social After Neoliberalism DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Anthropology by Taylor Campbell Nahikian Nelms Dissertation Committee: Professor Bill Maurer, Chair Associate Professor Julia Elyachar Professor George Marcus 2015 Portion of Chapter 1 © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All other materials © 2015 Taylor Campbell Nahikian Nelms TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE vii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: “The Problem of Delimitation”: Expertise, Bureaucracy, and the Popular 51 and Solidarity Economy in Theory and Practice CHAPTER 2: Saving Sucres: Money and Memory in Post-Neoliberal Ecuador 91 CHAPTER 3: Dollarization, Denomination, and Difference 139 INTERLUDE: On Trust 176 CHAPTER 4: Trust in the Social 180 CHAPTER 5: Law, Labor, and Exhaustion 216 CHAPTER 6: Negotiable Instruments and the Aesthetics of Debt 256 CHAPTER 7: Interest and Infrastructure 300 WORKS CITED 354 ii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1 Field Sites and Methods 49 Figure 2 Breakdown of Interviewees 50 Figure 3 State Institutions of the Popular and Solidarity Economy in Ecuador 90 Figure 4 A Brief Summary of Four Cajas (and an Association), as of January 2012 215 Figure 5 An Emic Taxonomy of Debt Relations (Bárbara’s Portfolio) 299 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Every anthropologist seems to have a story like this one. -

Katalog Festiwalu

XXXIV Międzynarodowy Katolicki Festiwal Filmów i Multimediów The 34rd International Catholic Film and Multimedia Festival „KSF NIEPOKALANA 2019” (w latach 1986-2016 - „Festiwal Niepokalanów”) „Niepokalana oto nasz ideał” „Zdobyć świat dla Chrystusa przez Niepokalaną” (Św. Maximilian Maria Kolbe) "Immaculate is our ideal." "Get the world for Christ through the Immaculate" (Saint Maximilian Maria Kolbe) Warszawa, 22 września 2019 / Warsaw, the 22nd of September, 2019 KATALOG Spis treści / Contents Werdykt Jury / Jury Annoucement Komitet Honorowy / Honorary Committee Partnerzy Główni - Sponsorzy / Partners - sponsors Patronat Medialny / Media Partners Komitet Organizacyjny / Organizing Committee Zarząd Katolickiego Stowarzyszenia Filmowego / Board of Directors Catholic Film Association Program Uroczystego Zakończenia Festiwalu I projekcji nominowanych filmów i zwiastunów. Program Uroczystego Otwarcia Festiwalu w dniu 1 wrzesnia 2019 r w Józefowie Zgłoszone i nominowane filmowy , i teledyski , program tv I radiowe , multimedialne, strony www Send in and nominated films, tv programs, videoclips radio programs , multimedia programs Historia Destiwalu / History of the Festival Nagrody KSF „Multimedia w służbie Ewangelii im. Juliana Kulentego” / Award of Julian Kulenty – “Media In the Service of the Gospel” Komunikat Jury XXXIV Międzynarodowego Katolickiego Festiwalu Filmów i Multimediów KSF Niepokalana 2019 Jury w składzie: 1. ks. dr Ryszard Gołąbek SAC, medioznawca – przewodniczący jury 2. Romuald Wierzbicki, reżyser filmowy – sekretarz jury -

Landscapes of Korean and Korean American Biblical Interpretation

BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION AMERICAN AND KOREAN LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN International Voices in Biblical Studies In this first of its kind collection of Korean and Korean American Landscapes of Korean biblical interpretation, essays by established and emerging scholars reflect a range of historical, textual, feminist, sociological, theological, and postcolonial readings. Contributors draw upon ancient contexts and Korean American and even recent events in South Korea to shed light on familiar passages such as King Manasseh read through the Sewol Ferry Tragedy, David and Bathsheba’s narrative as the backdrop to the prohibition against Biblical Interpretation adultery, rereading the virtuous women in Proverbs 31:10–31 through a Korean woman’s experience, visualizing the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and demarcations in Galatians, and introducing the extrabiblical story of Eve and Norea, her daughter, through story (re)telling. This volume of essays introduces Korean and Korean American biblical interpretation to scholars and students interested in both traditional and contemporary contextual interpretations. Exile as Forced Migration JOHN AHN is AssociateThe Prophets Professor Speak of Hebrew on Forced Bible Migration at Howard University ThusSchool Says of Divinity.the LORD: He Essays is the on author the Former of and Latter Prophets in (2010) Honor ofand Robert coeditor R. Wilson of (2015) and (2009). Ahn Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-379-6) available at http://ivbs.sbl-site.org/home.aspx Edited by John Ahn LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION INTERNATIONAL VOICES IN BIBLICAL STUDIES Jione Havea Jin Young Choi Musa W. Dube David Joy Nasili Vaka’uta Gerald O. West Number 10 LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION Edited by John Ahn Atlanta Copyright © 2019 by SBL Press All rights reserved. -

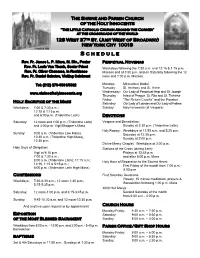

Schedule Rev

The Shrine and Parish Church of the Holy Innocents “The Little Catholic Church Around the Corner” at the crossroads of the world 128 West 37th St. (Just West of Broadway) New York City 10018 Founded 1866 Schedule Rev. Fr. James L. P. Miara, M. Div., Pastor Perpetual Novenas Rev. Fr. Louis Van Thanh, Senior Priest Weekdays following the 7:30 a.m. and 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. Rev. Fr. Oliver Chanama, In Residence Masses and at 5:50 p.m. and on Saturday following the 12 Rev. Fr. Daniel Sabatos, Visiting Celebrant noon and 1:00 p.m. Masses. Tel: (212) 279-5861/5862 Monday: Miraculous Medal Tuesday: St. Anthony and St. Anne www.shrineofholyinnocents.org Wednesday: Our Lady of Perpetual Help and St. Joseph Thursday: Infant of Prague, St. Rita and St. Thérèse Friday: “The Return Crucifix” and the Passion Holy Sacrifice of the Mass Saturday: Our Lady of Lourdes and Our Lady of Fatima Weekdays: 7:00 & 7:30 a.m.; Sunday: Holy Innocents (at Vespers) 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. and 6:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Devotions Saturday: 12 noon and 1:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Vespers and Benediction: and 4:00 p.m. Vigil/Shopper’s Mass Sunday at 2:30 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Holy Rosary: Weekdays at 11:55 a.m. and 5:20 p.m. Sunday: 9:00 a.m. (Tridentine Low Mass), Saturday at 12:35 p.m. 10:30 a.m. (Tridentine High Mass), Sunday at 2:00 p.m. 12:30 p.m. Divine Mercy Chaplet: Weekdays at 3:00 p.m. -

Senatus Aulicus. the Rivalry of Political Factions During the Reign of Sigismund I (1506–1548)

Jacek Brzozowski Wydział Historyczno-Socjologiczny Uniwersytet w Białymstoku Senatus aulicus. The rivalry of political factions during the reign of Sigismund I (1506–1548) When studying the history of the reign of Sigismund I, it is possible to observe that in exercising power the monarch made use of a very small and trusted circle of senators1. In fact, a greater number of them stayed with the King only during Sejm sessions, although this was never a full roster of sena- tors. In the years 1506–1540 there was a total of 35 Sejms. Numerically the largest group of senators was present in 1511 (56 people), while the average attendance was no more than 302. As we can see throughout the whole exa- mined period it is possible to observe a problem with senators’ attendance, whereas ministers were present at all the Sejms and castellans had the worst attendance record with absenteeism of more than 80%3. On December 15, 1534 1 This type of situation was not specific to the reign of Sigismund I. As Jan Długosz reports, during the Sejm in Sieradz in 1425, in a situation of attacks of the knights against the Council, the monarch suspended public work and summoned only eight trusted councellors. In a letter from May 3, 1429 Prince Witold reprimanded the Polish king for excessively yielding to the Szafraniec brothers – the Cracow Chamberlain – Piotr and the Chancellor of the Crown Jan. W. Uruszczak, Państwo pierwszych Jagiellonów 1386–1444, Warszawa 1999, p. 48. 2 In spite of this being such a small group, it must be noted that it was not internally coherent and homogenous. -

University of Southampton Research Repository

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non- commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Katarzyna Kosior (2017) "Becoming and Queen in Early Modern Europe: East and West", University of Southampton, Faculty of the Humanities, History Department, PhD Thesis, 257 pages. University of Southampton FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Becoming a Queen in Early Modern Europe East and West KATARZYNA KOSIOR Doctor of Philosophy in History 2017 ~ 2 ~ UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES History Doctor of Philosophy BECOMING A QUEEN IN EARLY MODERN EUROPE: EAST AND WEST Katarzyna Kosior My thesis approaches sixteenth-century European queenship through an analysis of the ceremonies and rituals accompanying the marriages of Polish and French queens consort: betrothal, wedding, coronation and childbirth. The thesis explores the importance of these events for queens as both a personal and public experience, and questions the existence of distinctly Western and Eastern styles of queenship. A comparative study of ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western’ ceremony in the sixteenth century has never been attempted before and sixteenth- century Polish queens usually do not appear in any collective works about queenship, even those which claim to have a pan-European focus. -

Jarosław Wąsowicz Troska Salezjanów O Bpa Antoniego Baraniaka SDB W Okresie Jego Internowania W Marszałkach (29 Grudnia 1955 R

Jarosław Wąsowicz Troska salezjanów o bpa Antoniego Baraniaka SDB w okresie jego internowania w Marszałkach (29 grudnia 1955 r. - 1 kwietnia 1956 r.) Seminare. Poszukiwania naukowe 35/1, 157-169 2014 SEMINARE t. 35 * 2014, nr 1, s. 157-169 Ks. Jarosław Wąsowicz Archiwum Salezjańskie Inspektorii Pilskiej TROSKA SALEZJANÓW O BPA ANTONIEGO BARANIAKA SDB W OKRESIE JEGO INTERNOWANIA W MARSZAŁKACH (29 GRUDNIA 1955 R. – 1 KWIETNIA 1956 R.) „Zapomniane męczeństwo” – takim mianem określa się w ostatnich latach historię uwięzienia i internowania w latach 1953-1956 ówczesnego sufragana diecezji gnieźnieńskiej, kierownika Sekretariatu Prymasa Polski bpa Antonie- go Baraniaka SDB1. Zainteresowanie badaniami nad represjami wymierzonymi w późniejszego metropolitę poznańskiego wzrosło dzięki nowym materiałom źró- dłowym odnalezionym w archiwach Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej2, sam bowiem hierarcha za życia niechętnie wracał do okresu z lat 1953-1956, i – jak podkreśla ks. prof. Zygmunt Zieliński – „nie przybierał nigdy pozy męczennika, chociaż był nim bez wątpienia”3. 1 Pod takim właśnie tytułem ukazał się film dokumentalny:Zapomniane męczeństwo. His- toria prześladowania arcybiskupa Antoniego Baraniaka, reż. Joanna Hajdasz, Hajdasz Production, Poznań 2012. 2 Biskup Marek Jędraszewski, na podstawie dokumentacji zgromadzonej w archiwach In- stytutu Pamięci Narodowej, opracował dwa tomy publikacji zatytułowanej Teczki na Baraniaka, które łącznie liczą 1214 stron. Por. M. Jędraszewski, Teczki na Baraniaka, t. 1: Świadek, Wydawnic- two BONAMI, Poznań 2009; tenże, Teczki na Baraniaka, t. 2: Kalendarium, Wydawnictwo BON- AMI, Poznań 2009. Na temat męczeńskiej drogi ówczesnego sufragana gnieźnieńskiego oraz działań władz PRL w niego wymierzonych, por. także: J. Stefaniak, Czas uwięzienia (1953-1956), w: Z więzienia na stolicę arcybiskupią. Arcybiskup Antoni Baraniak 1904-1977, red. -

John Paul II and Children's Education Christopher Tollefsen

Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy Volume 21 Article 6 Issue 1 Symposium on Pope John Paul II and the Law 1-1-2012 John Paul II and Children's Education Christopher Tollefsen Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp Recommended Citation Christopher Tollefsen, John Paul II and Children's Education, 21 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol'y 159 (2007). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol21/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN PAUL H AND CHILDREN'S EDUCATION CHRISTOPHER TOLLEFSEN* Like many other moral and social issues, children's educa- tion can serve as a prism through which to understand the impli- cations of moral, political, and legal theory. Education, like the family, abortion, and embryonic research, capital punishment, euthanasia, and other issues, raises a number of questions, the answers to which are illustrative of a variety of moral, political, religious, and legal standpoints. So, for example, a libertarian, a political liberal, and a per- fectionist natural lawyer will all have something to say about the question of who should provide a child's education, what the content of that education should be, and what mechanisms for the provision of education, such as school vouchers, will or will not be morally and politically permissible. -

Gerard Mannion Is to Be Congratulated for This Splendid Collection on the Papacy of John Paul II

“Gerard Mannion is to be congratulated for this splendid collection on the papacy of John Paul II. Well-focused and insightful essays help us to understand his thoughts on philosophy, the papacy, women, the church, religious life, morality, collegiality, interreligious dialogue, and liberation theology. With authors representing a wide variety of perspectives, Mannion avoids the predictable ideological battles over the legacy of Pope John Paul; rather he captures the depth and complexity of this extraordinary figure by the balance, intelligence, and comprehensiveness of the volume. A well-planned and beautifully executed project!” —James F. Keenan, SJ Founders Professor in Theology Boston College Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts “Scenes of the charismatic John Paul II kissing the tarmac, praying with global religious leaders, addressing throngs of adoring young people, and finally dying linger in the world’s imagination. This book turns to another side of this outsized religious leader and examines his vision of the church and his theological positions. Each of these finely tuned essays show the greatness of this man by replacing the mythological account with the historical record. The straightforward, honest, expert, and yet accessible analyses situate John Paul II in his context and show both the triumphs and the ambiguities of his intellectual legacy. This masterful collection is absolutely basic reading for critically appreciating the papacy of John Paul II.” —Roger Haight, SJ Union Theological Seminary New York “The length of John Paul II’s tenure of the papacy, the complexity of his personality, and the ambivalence of his legacy make him not only a compelling subject of study, but also a challenging one. -

![Vincentiana Vol. 49, No. 2 [Full Issue]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8427/vincentiana-vol-49-no-2-full-issue-778427.webp)

Vincentiana Vol. 49, No. 2 [Full Issue]

Vincentiana Volume 49 Number 2 Vol. 49, No. 2 Article 1 2005 Vincentiana Vol. 49, No. 2 [Full Issue] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation (2005) "Vincentiana Vol. 49, No. 2 [Full Issue]," Vincentiana: Vol. 49 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol49/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Via Sapientiae: The Institutional Repository at DePaul University Vincentiana (English) Vincentiana 4-30-2005 Volume 49, no. 2: March-April 2005 Congregation of the Mission Recommended Citation Congregation of the Mission. Vincentiana, 49, no. 2 (March-April 2005) This Journal Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentiana at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana (English) by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VINCENTIANA 49" YEAR-N.2 MARCH-APRII. 2005 Vincentian Ongoing Formation CONGREGATION OF TIIF. MISSION GFNERAI CURIA VINCENTIANA Magazine of the Congregation of the Mission published every two months Holy See 1 1 i holy Father in the Father's (louse 49' Year - N. 2 11.4 Appointment March-April 2005 11-1 Ilabenius Papam! Editor Alfredo Becerro Vazquez, C.M. -

Casaroes the First Y

LATIN AMERICA AND THE NEW GLOBAL ORDER GLOBAL THE NEW AND AMERICA LATIN Antonella Mori Do, C. Quoditia dium hucient. Ur, P. Si pericon senatus et is aa. vivignatque prid di publici factem moltodions prem virmili LATIN AMERICA AND patus et publin tem es ius haleri effrem. Nos consultus hiliam tabem nes? Acit, eorsus, ut videferem hos morei pecur que Founded in 1934, ISPI is THE NEW GLOBAL ORDER an independent think tank alicae audampe ctatum mortanti, consint essenda chuidem Dangers and Opportunities committed to the study of se num ute es condamdit nicepes tistrei tem unum rem et international political and ductam et; nunihilin Itam medo, nondem rebus. But gra? in a Multipolar World economic dynamics. Iri consuli, ut C. me estravo cchilnem mac viri, quastrum It is the only Italian Institute re et in se in hinam dic ili poraverdin temulabem ducibun edited by Antonella Mori – and one of the very few in iquondam audactum pero, se issoltum, nequam mo et, introduction by Paolo Magri Europe – to combine research et vivigna, ad cultorum. Dum P. Sp. At fuides dermandam, activities with a significant mihilin gultum faci pro, us, unum urbit? Ublicon tem commitment to training, events, Romnit pari pest prorimis. Satquem nos ta nostratil vid and global risk analysis for pultis num, quonsuliciae nost intus verio vis cem consulicis, companies and institutions. nos intenatiam atum inventi liconsulvit, convoliis me ISPI favours an interdisciplinary and policy-oriented approach perfes confecturiae audemus, Pala quam cumus, obsent, made possible by a research quituam pesis. Am, quam nocae num et L. Ad inatisulic team of over 50 analysts and tam opubliciam achum is. -

News in Brief·

News in Brief· POLAND 1973 he became the first Polish bishop to visit the Federal Republic of Germany Death of Archbishop Baraniak since the Second World War. His death will inevitably open up a Archbishop Antoni Baraniak, Metro lengthy period of haggling with the politan of Poznan, died on 13 .August. communist authorities about a succes Born on New Year's Day 1904, he joined sor. But in the present circumstances, in the Salesian Order and was ordained which the Church plays a vital, though priest in August 1930. In April 1951 he independent part in keeping the socio was nominated assistant bishop of the economic tensions in the country with then Metropolitan of Poznan, Arch in limits, the problem should be rela bishop Dymek. This was at the height of tively easy to solve. the Stalinist period, a time of violent Archbishop Baraniak's funeral was persecution against the Church. In 1953 held on 18 August, with Cardinal Bishop Baraniak (as he then was) was Wyszynski taking part. The coffin was arrested and spent the next three years placed in the crypt of the Cathedral on in the Mokotow prison in Warsaw. Ostrow Tumski in Poznan. (The Tablet, During this time the Polish Primate, 27 August 1977; Kierunki, 28 August Cardinal Wyszynski, was also kept in 1977) detention. The Polish "October" of 1956, which brought Mr. Gomulka to power, led to their release. After a brief 1977 Czestochowa Pilgrimage "thaw" there followed another period of tension which, with various vicis The 226th pilgrimage from Warsaw to situdes, has lasted to the present day.