Polonia Restituta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Threshold of the Holocaust: Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms In

Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. of the Holocaust carried out by the local population. Who took part in these excesses, and what was their attitude towards the Germans? The Author Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms Were they guided or spontaneous? What Tomasz Szarota is Professor at the Insti- part did the Germans play in these events tute of History of the Polish Academy in Occupied Europe and how did they manipulate them for of Sciences and serves on the Advisory their own benefit? Delving into the source Board of the Museum of the Second Warsaw – Paris – The Hague – material for Warsaw, Paris, The Hague, World War in Gda´nsk. His special interest Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Kaunas, this comprises WWII, Nazi-occupied Poland, Amsterdam – Antwerp – Kaunas study is the first to take a comparative the resistance movement, and life in look at these questions. Looking closely Warsaw and other European cities under at events many would like to forget, the the German occupation. On the the Threshold of Holocaust ISBN 978-3-631-64048-7 GEP 11_264048_Szarota_AK_A5HC PLE edition new.indd 1 31.08.15 10:52 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. -

Poglądy Społeczno-Polityczne Kardynała Prymasa Augusta Hlonda (1926-1948)

Tomasz Serwatka Poglądy społeczno-polityczne kardynała Prymasa Augusta Hlonda (1926-1948) Wrocławski Przegląd Teologiczny 13/1, 125-167 2005 WROCŁAWSKI PRZEGLĄD TEOLOGICZNY 13 (2005) nr 1 TOMASZ SERWATKA (WROCŁAW) POGLĄDY SPOŁECZNO-POLITYCZNE KARDYNAŁA PRYMASA AUGUSTA HLONDA (1926-1948) Pozycja polityczno-prestiżowa prymasów Polski - którymi wedle tradycji, a od 1418 r. formalnie, byli arcybiskupi gnieźnieńscy1-byłazawsze stosunkowo wyso ka. W okresie I Rzeczypospolitej szlacheckiej występowali w roli interreksów, każdorazowo po śmierci króla zwołując wolną elekcję (przykładowo 1572-1573, 1574-1575, 1587 r. i następne)2. Degrengolada, a potem całkowity upadek Polski (XVIK-XIX w.) spłyciły i podważyły również i rolę prymasów3. Pod zaborem pru skim arcybiskupi gnieźnieńscy byli paraliżowani w swych poczynaniach natury społecznej i politycznej przez rząd w Berlinie, a okresowo nawet represjonowani (abp Mieczysław Ledóchowski)4. Wzrosła za to rola arcypasterzy warszawskich, jako - od roku 1818 - „prymasów Królestwa Polskiego” (Kongresówka pod zabo rem rosyjskim). Najwybitniejsi spośród nich to Zygmunt Szczęsny Feliński i Alek sander Kakowski. W momencie odrodzenia się państwa polskiego, w 1918 r., powstała tedy swe go rodzaju dwuwładza prymasowska. O ile metropolita gnieźnieński (rezydujący w Poznaniu), kardynał Edmund Dalbor, wedle dawnej tradycji został uznany za 1 Por. przykładowo Poczet Prymasów Polski, oprać. H.J. Kaczmarski, Warszawa 1988, s. 65, 202. 2P. Jasienica, Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów, cz. I, Warszawa 1982, s. 37, 86,92,158. 3 Ostatni prymas I Rzeczypospolitej, wybitny poeta i publicysta, abp Ignacy Krasicki, musiał podporządkować się protestanckiemu królowi pruskiemu (1795), w którego zaborze znajdowały się polskie stolice prymasowskie oraz rezydencja w Łowiczu; por. Z. Goliński, Ignacy Krasicki, War szawa 1979, s. 394-395. 4Poczet..., s. -

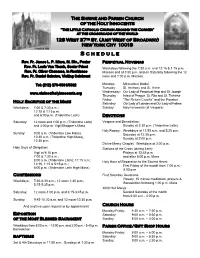

Schedule Rev

The Shrine and Parish Church of the Holy Innocents “The Little Catholic Church Around the Corner” at the crossroads of the world 128 West 37th St. (Just West of Broadway) New York City 10018 Founded 1866 Schedule Rev. Fr. James L. P. Miara, M. Div., Pastor Perpetual Novenas Rev. Fr. Louis Van Thanh, Senior Priest Weekdays following the 7:30 a.m. and 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. Rev. Fr. Oliver Chanama, In Residence Masses and at 5:50 p.m. and on Saturday following the 12 Rev. Fr. Daniel Sabatos, Visiting Celebrant noon and 1:00 p.m. Masses. Tel: (212) 279-5861/5862 Monday: Miraculous Medal Tuesday: St. Anthony and St. Anne www.shrineofholyinnocents.org Wednesday: Our Lady of Perpetual Help and St. Joseph Thursday: Infant of Prague, St. Rita and St. Thérèse Friday: “The Return Crucifix” and the Passion Holy Sacrifice of the Mass Saturday: Our Lady of Lourdes and Our Lady of Fatima Weekdays: 7:00 & 7:30 a.m.; Sunday: Holy Innocents (at Vespers) 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. and 6:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Devotions Saturday: 12 noon and 1:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Vespers and Benediction: and 4:00 p.m. Vigil/Shopper’s Mass Sunday at 2:30 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Holy Rosary: Weekdays at 11:55 a.m. and 5:20 p.m. Sunday: 9:00 a.m. (Tridentine Low Mass), Saturday at 12:35 p.m. 10:30 a.m. (Tridentine High Mass), Sunday at 2:00 p.m. 12:30 p.m. Divine Mercy Chaplet: Weekdays at 3:00 p.m. -

Gerard Mannion Is to Be Congratulated for This Splendid Collection on the Papacy of John Paul II

“Gerard Mannion is to be congratulated for this splendid collection on the papacy of John Paul II. Well-focused and insightful essays help us to understand his thoughts on philosophy, the papacy, women, the church, religious life, morality, collegiality, interreligious dialogue, and liberation theology. With authors representing a wide variety of perspectives, Mannion avoids the predictable ideological battles over the legacy of Pope John Paul; rather he captures the depth and complexity of this extraordinary figure by the balance, intelligence, and comprehensiveness of the volume. A well-planned and beautifully executed project!” —James F. Keenan, SJ Founders Professor in Theology Boston College Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts “Scenes of the charismatic John Paul II kissing the tarmac, praying with global religious leaders, addressing throngs of adoring young people, and finally dying linger in the world’s imagination. This book turns to another side of this outsized religious leader and examines his vision of the church and his theological positions. Each of these finely tuned essays show the greatness of this man by replacing the mythological account with the historical record. The straightforward, honest, expert, and yet accessible analyses situate John Paul II in his context and show both the triumphs and the ambiguities of his intellectual legacy. This masterful collection is absolutely basic reading for critically appreciating the papacy of John Paul II.” —Roger Haight, SJ Union Theological Seminary New York “The length of John Paul II’s tenure of the papacy, the complexity of his personality, and the ambivalence of his legacy make him not only a compelling subject of study, but also a challenging one. -

Część I: Artykuły

Rozprawy Społeczne 2011, Tom V, Nr 2 Relacje państwo – Kościół Katolicki.... CZĘŚĆ I: ARTYKUŁY RELACJE PAŃSTWO – KOŚCIÓŁ KATOLICKI W ŚWIETLE DYPLOMATYCZNYCH STOSUNKÓW Z WATYKANEM W LATACH 1918-1939 RozprawySławomir Społeczne Bylina Nr 2 (V) 2011 Instytut Teologiczny w Siedlcach Streszczenie - : Relacje pomiędzy stroną państwową i kościelną, to istotny aspekt życia ludzkiego, jaki istnieje od początku naszej ery. Celem artykułu jest ukazanie zasadniczych elementów, które miały wpływ na budowanie więzi państwo – Koś ciół katolicki w wymiarze powszechnym. Poprzez kwerendę archiwalną i przy pomocy zebranej literatury przedmiotu zbadano drogę, która prowadziła do odnowienia i kontynuacji oficjalnych stosunków dyplomatycznych pomiędzy Polską a Stolicą Apostolską w okresie międzywojennym. Należy zauważyć, że stanowisko Watykanu wobec sprawy polskiej było- istotnym elementem zabiegów dyplomatycznych kolejnych papieży okresu pomiędzy wojnami światowymi. Wymienione zależności jakie miały miejsce w latach 1918-1939 ukazują również aktualne postawy ludzi wierzących, którzy w zdecydo Słowawanej większościkluczowe: stanowią obywatele, gdzie dominuje wyznanie rzymsko-katolickie w tym szczególnie Polski. państwo, Kościół katolicki, Stolica Apostolska, konkordat, nuncjusz apostolski Wstęp - - w postaci deklaracji politycznych, które z ramienia - dyplomacji watykańskiej były moralnym wspar- Wspólne więzi jakie panowały pomiędzy Rzeczy ciem w zagrożeniu przez trzech zaborców narodu- pospolitą a Stolicą Apostolską rozpoczęły się w mo polskiego. Papież rozwinął krucjatę modlitwy o po mencie Chrztu Polski w 966 r., który był początkiem- kój oraz ogłaszał liczne apele pokojowe. Z począt- pierwszych deklaracji i dokumentów, zawieranych kiem sierpnia 1917 r. przedstawił krajom, oraz ich na szczeblu międzynarodowym. Dokument „ Dago rządom, które brały udział w wojnie jasny i sprecy- me iudex”, wizyty legatów, ustanowienie nuncjatury- zowany plan tzw. Punktację Pacellego składającą się w Polsce w 1515 r. -

August Hlond Biskupem. Vir Ecclesiasticus Według Pastores Gregis

Nauczyciel i Szkoła 2019/2, nr 70 ISSN 1426-9899, e-ISSN 2544-6223 DOI: 10.14632/NiS.2019.70.37 Maria Włosek ORCID: 0000-0001-8356-866X Wyższa Szkoła im. B. Jańskiego w Warszawie Wydział Zamiejscowy w Krakowie August Hlond biskupem. Vir Ecclesiasticus według Pastores gregis August Hlond as a Bishop. Vir Ecclesiaticus According to Pastores Gregis STRESZCZENIE Papież Jan Paweł II w adhortacji apostolskiej Pastores gregis określił zada- nia biskupa w naszych czasach. Jedną z zasadniczych cech posługi bisku- piej jest dawanie nadziei swojemu ludowi. Kardynał August Hlond jako biskup i Prymas Polski, tworząc nowe instytucje i nową strukturę Kościoła w Polsce, a także nauczając, dawał nadzieję i był prawdziwie mężem Koś- cioła. Owocem jego działalności pasterskiej była poniekąd duchowość papieża Jana Pawła II. SUMMARY Pope John Paul II, in the apostolic exhortation Pastores Gregis, gave us the image of a bishop of our times. According this document, one of the main tasks of a bishop is to give hope to the people. The article is demonstra- ting that August Hlond, as a bishop and Primate of Poland, through the creation of new institutions and a new ecclesiastical structure in Poland, and through his teaching, truly gave hope, being a real vir ecclesiaticus. In a way, one of the fruits of his pastoral activity was Pope John Paul II. SŁOWA KLUCZE kardynał Hlond, biskup nadziei, człowiek Kościoła KEYWORDS Cardinal August Hlond, bishop of hope, man of the Church 38 MARIA Włosek Działania Augusta Hlonda, kardynała i prymasa Polski, postrzegamy jako dzieła dobrego pasterza, głoszącego nadzieję eschatologiczną i doczesną. -

The Roman Catholic Clergy, the Byzantine Slavonic Rite and Polish National Identity: the Case of Grabowiec, 1931-341

Religion, State & Society, Vo!. 28, No. 2, 2000 The Roman Catholic Clergy, the Byzantine Slavonic Rite and Polish National Identity: The Case of Grabowiec, 1931-341 KONRAD SADKOWSKI In November 1918 Poland returned to the map of Europe as an independent state. After its borders were finalised in 1921-22 Poland was a distinctly multinational state, with approximately one-third of its population being ethnic Poles. Two of the largest minority groups were the Ukrainians and Belarusians, who resided in Poland's eastern and south-eastern kresy (borderlands).2 Until the First World War, however, the territory these groups lived on was part of the Russian and Austro Hungarian Empires. Indeed, the Ukrainians lived divided between the two empires. At the chaotic conclusion of the First World War both the Ukrainians and Bela rusians made unsuccessful bids for independence. For the former this included a bloody war with the Poles in 1918-19. Prior to the partitioning of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by Russia, Prussia and Austria in the late eighteenth century, the majority of the Ukrainians and Belarusians of this state adhered to the Greek Catholic (Uniate) rite in the Roman Church. The Uniate Church was created through the Union of Brest of 1596, engineered to bring the Commonwealth's Christian Orthodox believers under Rome's jurisdiction. In Russia the Uniate Church did not survive the partition years; it was abolished in the Western Provinces in 1839 and in the Kingdom of Poland in 1875. The Uniates were forced to adopt Russian Orthodoxy, though some resisted. In Galicia (the territory acquired by Austria in the partitions), however, the Uniate Church continued to thrive. -

From Memory to Freedom Research on Polish Thinking About National Security and Political Community

Cezary Smuniewski From Memory to Freedom Research on Polish Thinking about National Security and Political Community Publication Series: Monographs of the Institute of Political Science Scientific Reviewers: Waldemar Kitler, War Studies Academy, Poland Agostino Massa, University of Genoa, Italy The study was performed under the 2017 Research and Financial Plan of War Studies Academy. Title of the project: “Bilateral implications of security sciences and reflection resulting from religious presumptions” (project no. II.1.1.0 grant no. 800). Translation: Małgorzata Mazurek Aidan Hoyle Editor: Tadeusz Borucki, University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland Typeseting: Manuscript Konrad Jajecznik © Copyright by Cezary Smuniewski, Warszawa 2018 © Copyright by Instytut Nauki o Polityce, Warszawa 2018 All rights reserved. Any reproduction or adaptation of this publication, in whole or any part thereof, in whatever form and by whatever media (typographic, photographic, electronic, etc.), is prohibited without the prior written consent of the Author and the Publisher. Size: 12,1 publisher’s sheets Publisher: Institute of Political Science Publishers www.inop.edu.pl ISBN: 978-83-950685-7-7 Printing and binding: Fabryka Druku Contents Introduction 9 1. Memory - the “beginning” of thinking about national security of Poland 15 1.1. Memory builds our political community 15 1.2. We learn about memory from the ancient Greeks and we experience it in a Christian way 21 1.3. Thanks to memory, we know who a human being is 25 1.4. From memory to wisdom 33 1.5. Conclusions 37 2. Identity – the “condition” for thinking about national security of Poland 39 2.1. Contemporary need for identity 40 2.2. -

Łysoń 1 Korekta.Indd

Rafał Łysoń Polskie ugrupowania ugodowe w Wielkim Księstwie Poznańskim w latach 1894–1918 Rafał Łysoń Rafał Łysoń, absolwent Wydziału Historycznego Uniwersytetu Adama Mickie- wicza, adiunkt w Pracowni Historii Niemiec i Stosunków Polsko-Niemieckich Instytutu Historii PAN. Swoje zainteresowania badawcze koncentruje na histo- rii Prus/Niemiec i stosunkach polsko-niemieckich w XIX i XX wieku. Autor kilku artykułów naukowych poświęconych problematyce ugodowości w zaborze pruskim, członek zespołu autorskiego powstającej w IH PAN czterotomowej historii Prus: Prusy. Narodziny – mocarstwo – obumieranie 1500–1947. Wiecznie proszący, nigdy nie wysłuchani Problem działalności polskich organizacji ugodowych w zaborze pruskim zawsze pozostawał w cieniu badań na ten temat w zaborach austriackim i rosyj- skim. Tymczasem działający w specyficznych warunkach ugodowcy Wielkiego Księstwa Poznańskiego są częścią historii polskiej działalności i myśli politycz- nej okresu, kiedy nie istniało państwo polskie. Praca niniejsza przedstawia strukturę, działalność, program polityczny oraz miejsce na scenie politycznej Poznańskiego organizacji ugodowych w ostatnim ćwierćwieczu rządów pruskich w tej prowincji. W obliczu nasilonej polityki germanizacyjnej i konfliktów narodowościowych trwanie na pozycjach ugodo- wych było szczególnie trudne. Praca jest analizą powodów, dlaczego w tych skrajnie niekorzystnych warunkach polscy zwolennicy tej opcji w Poznańskiem przetrwali prawie do końca rządów pruskich. Osobne miejsce poświęcił autor roli i działalności poznańskich -

LIC CHURCH in POLAND the History of Evolution of Catholic Church's

2. CHANGES OF TERRITORIAL STRUCTURE OF THE CATHO- LIC CHURCH IN POLAND1 The history of evolution of Catholic Church’s administrative-territorial structure in Poland can be divided into seven periods (cf. Kumor 1969) determined by historic turning points and administrative reforms of the Church itself: − Independent Poland (968 – 1772/95), − Partition period (1772/95 – 1918), − Interwar period (1918 – 1939), − Nazi occupation years (1939-1945) − First period of the People’s Republic of Poland – the biggest persecu- tions of the Catholic Church (1945 – 1972), − Second period of the People’s Republic of Poland (1972 – 1992), − Period after the great administrative reform of the Church in Poland, time of Polish transformation (after 1992). During the first, and at the same time the longest period, there have been two metropolises2 in Poland – in Gniezno (since 1000) and in Lvov (since 1375). However, the first bishopric and diocese – in Poznań was founded soon after the baptism of Poland (966/967). During the congress of Gniezno in the year 1000 the papal bulls were announced and introduced the first church province in Poland. The borders of the new metropolis3 and Diocese of Poznań were the same as the borders of Poland during this period (Jaku- bowski, Solarczyk 2007; Kumor 2003a) – cf. Map 1. As E. Wiśniowski (2004) underlines, the parish network, or more specifically – the church network was developing on the basis of the existing network of fortresses, especially those of major economic significance. Such locations enabled Christianization of neighbouring lands, and when needed, defense of clergy and churches from potential threats. In the ages to come, administrative structure of the Church was very dynamic. -

Marian Renewal-Final41600

THE RENEWAL OF THE MARIAN ORDER IN 1909 - 1910 The Renewal of The Marian Order In 1909 - 1910 Edited by Rev. Jan Bukowicz MIC Tadeusz Gorski MIC MARIAN PRESS Marians of the Immaculate Conception Stockbridge, Massachusetts 01263 2000 Copyright © 2000 Marians of the Immaculate Conception All rights reserved. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 00-102599 ISBN 0-944203-31-0 Project coordinator and art selection for cover: Andrew R. Maczynski, MIC Translation and editing from Polish into English: Piotr Graff Copy Editing: Sarah Novak Proofreading: David Came Stephen LaChance Mary Ellen McDonald Typesetting: Mary Ellen McDonald Cover Design: Bill Sosa Printed in the United States of America Stockbridge, Massachusetts 01263 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ......................................................................................................1 List of Abbreviations ...............................................................................5 Introduction ..............................................................................................7 Abolition and an attempt to renew the Order legally.........................8 Beginnings of the reform of the Congregation of Marian Fathers ........................................................................................13 Approval of the constitutions and of the reformed Congregation..............................................................................21 The growth of the Congregation under the leadership of Rev. Jerzy Matulewicz ..........................................................29 -

Rev. Dr. Edmund Nowicki – Apostolic Administrator in Gorzów Wielkopolski

Studia Theologica Varsaviensia UKSW 2/2019 rev. GrzeGorz wejMan ReV. DR. EDMUND NOWICKi – APostolIC ADMINIstRatoR IN GoRZÓW WIelKOPolsKI IntroDUction Protonotary Apostolic Rev. dr. Edmund Nowicki of the archdiocese of Gniezno and Poznań was deeply attached to the city of Gorzów Wielkopolski through his priestly ministry, and to the city of Gdańsk through his episcopal ministry. Work in the Apostolic Administration in Gorzów Wielkopolski was particularly difficult for him. A huge area – 1/7 of the territory of Poland, lack of basic pastoral tools and obstructions created by the then state authorities caused extremely big problems with building the foundations of pastoral life in the church newly-created in this land. Still, his fortitude, solid theological and legal background, as well as personal sensitivity bore the expected fruit of the well-functioning apostolic administration. Three major publications were published on the life and activity of Edmund Nowicki. In 1998 Rev. Stanisław Bogdanowicz pub- lished a book entitled “Edmund Nowicki, the bishop of Gdańsk”. Collective work edited by Rev. Henryk Jankowski entitled “Bishop Edmund Nowicki 1956-1971” was published in 1996 to commemorate the 25th anniversary of death of the bishop of Gdańsk. The main item is the doctoral thesis of Rev. Edward Napierała entitled “Historia Administracji Apostolskiej w Gorzowie Wlkp. za rządów ks. dr. 72 Stanisław MŁYNARSKI [2] Edmunda Nowickiego (1945-1951)”, gives an account of the birth and development of the administration in Gorzów1. This paper presents the most important pastoral achievements of Rev. Edmund Nowicki in the perspective of his appointment as the apostolic administrator and his organizational, pastoral and personal ministry in Gorzów Wielkopolski summed up with the most important events in his life of a priest and a bishop.