Casaroes the First Y

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Realignment in Brazil: Jair Bolsonaro and the Right Turn

Revista de Estudios Sociales 69 | 01 julio 2019 Temas varios Political Realignment in Brazil: Jair Bolsonaro and the Right Turn Realineamiento político en Brasil: Jair Bolsonaro y el giro a la derecha Realinhamento político no Brasil: Jair Bolsonaro e o giro à direita Fabrício H. Chagas Bastos Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/revestudsoc/46149 ISSN: 1900-5180 Publisher Universidad de los Andes Printed version Date of publication: 1 July 2019 Number of pages: 92-100 ISSN: 0123-885X Electronic reference Fabrício H. Chagas Bastos, “Political Realignment in Brazil: Jair Bolsonaro and the Right Turn”, Revista de Estudios Sociales [Online], 69 | 01 julio 2019, Online since 09 July 2019, connection on 04 May 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/revestudsoc/46149 Los contenidos de la Revista de Estudios Sociales están editados bajo la licencia Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. 92 Political Realignment in Brazil: Jair Bolsonaro and the Right Turn * Fabrício H. Chagas-Bastos ** Received date: April 10, 2019· Acceptance date: April 29, 2019 · Modification date: May 10, 2019 https://doi.org/10.7440/res69.2019.08 How to cite: Chagas-Bastos, Fabrício H. 2019. “Political Realignment in Brazil: Jair Bolsonaro and the Right Turn”. Revista de Estudios Sociales 69: 92-100. https://doi.org/10.7440/res69.2019.08 ABSTRACT | One hundred days have passed since Bolsonaro took office, and there are two salient aspects of his presidency: first, it is clear that he was not tailored for the position he holds; second, the lack of preparation of his entourage and the absence of parliamentary support has led the country to a permanent state of crisis. -

55 130516 Informe Especial El Congreso Argentino.Indd

SPECIAL REPORT The Argentinian Congress: political outlook in an election year Buenos Aires, May 2013 BARCELONA BOGOTÁ BUENOS AIRES LIMA LISBOA MADRID MÉXICO PANAMÁ QUITO RIO J SÃO PAULO SANTIAGO STO DOMINGO THE ARGENTINIAN CONGRESS: POLITICAL OUTLOOK IN AN ELECTION YEAR 1. INTRODUCTION 1. INTRODUCTION 2. WHAT HAPPENED IN 2012? 3. 2013 OUTLOOK On 1st March 2013, the president of Argentina, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, opened a new regular sessions’ period in the Argentinian 4. JUSTICE REFORM AND ITS Congress. POLITICAL CONSEQUENCES 5. 2013 LEGISLATIVE ELECTIONS In her message, broadcasted on national radio and television, the 6. CONCLUSIONS head of state summarized the main economic indicators of Argentina AUTHORS and how they had developed over the last 10 years of Kirchner’s LLORENTE & CUENCA administration, a timeframe she called “a won decade”. National deputies and senators, in Legislative Assembly, attended the Presidential speech after having taken part in 23 sessions in each House, which strongly contrasts with the fi gure registered in 2011, when approximately a dozen sessions were held. The central point of her speech was the announcement of the outlines of what she called “the democratization of justice”. The modifi cation of the Judicial Council, the creation of three new Courts of Cassation and the regulation of the use of precautionary measures in lawsuits against the state were, among others, the initiatives that the president promised to send to Congress for discussion. Therefore, the judicial system reform became the main political issue in the 2013 public agenda and had a noteworthy impact on all areas of Argentinian society. -

'Civil Society Works for a Democracy That Is Not Only More Representative

‘Civil society works for a democracy that is not only more representative but also more participatory’ CIVICUS speaks to Ramiro Orias, a Bolivian lawyer and human rights defender. Orias is a program officer with the Due Process of Law Foundation and a member and former director of Fundación Construir, a Bolivian CSO aimed at promoting citizen participation process for the strengthening of democracy and equal access to plural, equitable, transparent and independent judicial institutions. Q: A few days ago a national protest against the possibility of a new presidential re-election took place in Bolivia. Do you see President Evo Morales’ new re-election attempt as an example of democratic degradation? The president’s attempt to seek another re-election is part of a broader process of erosion of democratic civic space that has resulted from the concentration of power. The quest for a new presidential re-election requires a reform of the 2009 Constitution (which was promulgated by President Evo Morales himself). Some of the provisions introduced into the new constitutional text were very progressive; they indeed implied significant advances in terms of rights and guarantees. On the other hand, political reforms aimed at consolidating the newly acquired power were also introduced. For instance, there was a change in the composition and political balances within the Legislative Assembly that was aimed at over-representing the majority; the main authorities of the judiciary were dismissed before the end of their terms (the justices of the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Tribunal were put to trial and forced to resign) and an election system for magistrates was established. -

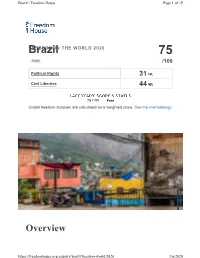

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Brazil | Freedom House Page 1 of 19 BrazilFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 75 FREE /100 Political Rights 31 Civil Liberties 44 75 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Brazil | Freedom House Page 2 of 19 Brazil is a democracy that holds competitive elections, and the political arena is characterized by vibrant public debate. However, independent journalists and civil society activists risk harassment and violent attack, and the government has struggled to address high rates of violent crime and disproportionate violence against and economic exclusion of minorities. Corruption is endemic at top levels, contributing to widespread disillusionment with traditional political parties. Societal discrimination and violence against LGBT+ people remains a serious problem. Key Developments in 2019 • In June, revelations emerged that Justice Minister Sérgio Moro, when he had served as a judge, colluded with federal prosecutors by offered advice on how to handle the corruption case against former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who was convicted of those charges in 2017. The Supreme Court later ruled that defendants could only be imprisoned after all appeals to higher courts had been exhausted, paving the way for Lula’s release from detention in November. • The legislature’s approval of a major pension reform in the fall marked a victory for Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was inaugurated in January after winning the 2018 election. It also signaled a return to the business of governing, following a period in which the executive and legislative branches were preoccupied with major corruption scandals and an impeachment process. -

Maria Da Penha

Global Feminisms Comparative Case Studies of Women’s Activism and Scholarship BRAZIL Maria da Penha Interviewer: Sueann Caulfield Fortaleza, Brazil February 2015 University of Michigan Institute for Research on Women and Gender 1136 Lane Hall Ann Arbor, MI 48109‐1290 Tel: (734) 764‐9537 E‐mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.umich.edu/~glblfem © Regents of the University of Michigan, 2015 Maria da Penha, born in 1945 in Fortaleza, Ceará, is a leader in the struggle against domestic violence in Brazil. Victimized by her husband in 1983, who twice tried to murder her and left her a paraplegic, she was the first to successfully bring a case of domestic violence to the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. It took years to bring the case to public attention. In 2001, the case resulted in the international condemnation of Brazil for neglect and for the systematic delays in the Brazilian justice system in cases of violence against women. Brazil was obliged to comply with certain recommendations, including a change to Brazilian law that would ensure the prevention and protection of women in situations of domestic violence and the punishment of the offender. The federal government, under President Lula da Silva, and in partnership with five NGOs and a number of important jurists, proposed a bill that was unanimously passed by both the House and the Senate. In 2006, Federal Law 11340 was ratified, known as the “Maria da Penha Law on Domestic and Family Violence.” Maria da Penha’s contribution to this important achievement for Brazilian women led her to receive significant honors, including "The Woman of Courage Award” from the United States in 2010.1 She also received the Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic from the Spanish Embassy, and in 2013, the Human Rights Award, which is considered the highest award of the Brazilian Government in the field of human rights. -

“Bringing Militancy to Management”: an Approach to the Relationship

“Bringing Militancy to Management”: An Approach to the Relationship between Activism 67 “Bringing Militancy to Management”: An Approach to the Relationship between Activism and Government Employment during the Cristina Fernández de Kirchner Administration in Argentina Melina Vázquez* Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET); Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani; Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina Abstract This article explores the relationship between employment in public administration and militant commitment, which is understood as that which the actors themselves define as “militant management.” To this end, an analysis is presented of three groups created within three Argentine ministries that adopted “Kirchnerist” ideology: La graN maKro (The Great Makro), the Juventud de Obras Públicas, and the Corriente de Libertación Nacional. The article explores the conditions of possibility and principal characteristics of this activism as well as the guidelines for admission, continuing membership, and promotion – both within the groups and within government entities – and the way that this type of militancy is articulated with expert, professional and academic capital as well as the capital constituted by the militants themselves. Keywords: Activism, expert knowledge, militant careers, state. * Article received on November 22, 2013; final version approved on March 26, 2014. This article is part of a series of studies that the author is working on as a researcher at CONICET and is part of the project “Activism and the Political Commitment of Youth: A Socio-Historical Study of their Political and Activist Experiences (1969-2011)” sponsored by the National Agency for Scientific and Technological Promotion, Argentine Ministry of Science, Technology and Productive Innovation (2012-2015), of which the author is the director. -

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations Updated July 6, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46236 SUMMARY R46236 Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations July 6, 2020 Occupying almost half of South America, Brazil is the fifth-largest and fifth-most-populous country in the world. Given its size and tremendous natural resources, Brazil has long had the Peter J. Meyer potential to become a world power and periodically has been the focal point of U.S. policy in Specialist in Latin Latin America. Brazil’s rise to prominence has been hindered, however, by uneven economic American Affairs performance and political instability. After a period of strong economic growth and increased international influence during the first decade of the 21st century, Brazil has struggled with a series of domestic crises in recent years. Since 2014, the country has experienced a deep recession, record-high homicide rate, and massive corruption scandal. Those combined crises contributed to the controversial impeachment and removal from office of President Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016). They also discredited much of Brazil’s political class, paving the way for right-wing populist Jair Bolsonaro to win the presidency in October 2018. Since taking office in January 2019, President Jair Bolsonaro has begun to implement economic and regulatory reforms favored by international investors and Brazilian businesses and has proposed hard-line security policies intended to reduce crime and violence. Rather than building a broad-based coalition to advance his agenda, however, Bolsonaro has sought to keep the electorate polarized and his political base mobilized by taking socially conservative stands on cultural issues and verbally attacking perceived enemies, such as the press, nongovernmental organizations, and other branches of government. -

The XXI Century Socialism in the Context of the New Latin American Left Civilizar

Civilizar. Ciencias Sociales y Humanas ISSN: 1657-8953 [email protected] Universidad Sergio Arboleda Colombia Ramírez Montañez, Julio The XXI century socialism in the context of the new Latin American left Civilizar. Ciencias Sociales y Humanas, vol. 17, núm. 33, julio-diciembre, 2017, pp. 97- 112 Universidad Sergio Arboleda Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=100254730006 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Civilizar Ciencias Sociales y Humanas 17 (33): 97-112, Julio-Diciembre de 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22518/16578953.902 The XXI century socialism in the context of the new Latin American left1 El socialismo del siglo XXI en el contexto de la nueva izquierda latinoamericana Recibido: 27 de juniol de 2016 - Revisado: 10 de febrero de 2017 – Aceptado: 10 de marzo de 2017. Julio Ramírez Montañez2 Abstract The main purpose of this paper is to present an analytical approach of the self- proclaimed “new socialism of the XXI Century” in the context of the transformations undertaken by the so-called “Bolivarian revolution”.The reforms undertaken by referring to the ideology of XXI century socialism in these countries were characterized by an intensification of the process of transformation of the state structure and the relations between the state and society, continuing with the nationalization of sectors of the economy, the centralizing of the political apparatus of State administration. -

Excelentíssimo Senhor Presidente Da Câmara Dos Deputados, Deputado Rodrigo Maia. Denúncia Por Crime De Responsabilidade

Página 1 de 39 EXCELENTÍSSIMO SENHOR PRESIDENTE DA CÂMARA DOS DEPUTADOS, DEPUTADO RODRIGO MAIA. Compromisso Constitucional do Presidente da República do Brasil Ao chegar no Congresso Nacional, eles são recebidos pelos Presidentes do Senado e da Câmara dos Deputados. Na presença dos 513 deputados, 81 senadores e de convidados, como chefes de estado ou seus representantes, o novo mandatário faz um juramento à nação, prestando o compromisso de: “Manter, defender e cumprir a Constituição, observar as leis, promover o bem geral do povo brasileiro, sustentar a união, a integridade e a independência do Brasil.” MARIA RODRIGUES DE SOUSA, viúva, das prendas domésticas, inscrita no CPF 120.917.231-34, portadora da CI 363.468 – SSP-DF, Título de Eleitor 62.207.820/97, Zona 009, Seção 0006, fones (61) 3568-1787 e 9 8131-4698 e, endereço eletrônico: [email protected]. LUIZ FERNANDO RABELO DE SOUSA, solteiro, servidor público, inscrita no CPF 238.927.651-20, portador da CI 515.476 – SSP-DF, Título de Eleitor 64.515.420/38, Zona 009, Seção 0086, fones (61) 3568 0976 e, endereço eletrônico: [email protected]. NEIDE LIAMAR RABELO DE SOUZA, solteira, economista, inscrita no CPF 182.225.791- 34, portadora da CI 521.457 DF, Título de Eleitor 62.248.220/20, Zona 009, Seção 0008, fones 0083 e, endereço eletrônico: [email protected]. ANDRÉ RABELO DE SOUSA, solteiro, professor, inscrita no CPF 329.687.441-00, portador da CI DF, Título de Eleitor 75.958.720/54, Zona 009, Seção 0019, fones (61) 3568 14 e, endereço eletrônico: [email protected]. -

Brazilian Foreign Policy on Twitter: Digital Expression of Attitudes in the Early Months of Bolsonaro’S Administration

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO INSTITUTO DE RELAÇÕES INTERNACIONAIS ANNA CAROLINA RAPOSO DE MELLO Brazilian Foreign Policy on Twitter: Digital Expression of Attitudes in the early months of Bolsonaro’s administration SÃO PAULO 2019 ANNA CAROLINA RAPOSO DE MELLO Brazilian Foreign Policy on Twitter: Digital Expression of Attitudes in the early months of Bolsonaro’s administration Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Relações Internacionais do Instituto de Relações Internacionais da Universidade de São Paulo, para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Feliciano de Sá Guimarães Versão corrigida A versão original se encontra disponível na Biblioteca do Instituto de Relações Internacionais SÃO PAULO 2019 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. Nome: Anna Carolina Raposo de Mello Título: Brazilian Foreign Policy on Twitter: Digital Expression of Attitudes in the early months of Bolsonaro’s administration Aprovada em 11 de dezembro de 2019 Banca Examinadora: Prof. Dr. Feliciano de Sá Guimarães (IRI-USP) Julgamento: Aprovada Prof.ª Drªa Denilde Oliveira Holzhacker (ESPM) Julgamnto: Aprovada Prof. Dr. Ivam Filipe de Almeida Lopes Fernandes (UFABC) Julgamento: Aprovada ABSTRACT MELLO, A. C. R., Brazilian Foreign Policy on Twitter: Digital Expression of Attitudes in the early months of Bolsonaro’s administration, 2019. 118p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Relações Internacionais) – Instituro de Relações Internacionais, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2019. This work addresses the impact of social media interactions in Brazilian foreign policy attitudes, as these digital platforms appear to be not only open floors for spontaneous manifestations of opinion, but also important sources of information. -

— — the Way We Will Work

No. 03 ASPEN.REVIEW 2017 CENTRAL EUROPE COVER STORIES Edwin Bendyk, Paul Mason, Drahomíra Zajíčková, Jiří Kůs, Pavel Kysilka, Martin Ehl POLITICS Krzysztof Nawratek ECONOMY Jacques Sapir CULTURE Olena Jennings INTERVIEW Alain Délétroz Macron— Is Not 9 771805 679005 No. 03/2017 No. 03/2017 Going to Leave Eastern Europe Behind — e-Estonia:— The Way We Will Work We Way The Between Russia and the Cloud The Way We Will Work About Aspen Aspen Review Central Europe quarterly presents current issues to the general public in the Aspenian way by adopting unusual approaches and unique viewpoints, by publishing analyses, interviews, and commentaries by world-renowned professionals as well as Central European journalists and scholars. The Aspen Review is published by the Aspen Institute Central Europe. Aspen Institute Central Europe is a partner of the global Aspen network and serves as an independent platform where political, business, and non-prof-it leaders, as well as personalities from art, media, sports and science, can interact. The Institute facilitates interdisciplinary, regional cooperation, and supports young leaders in their development. The core of the Institute’s activities focuses on leadership seminars, expert meetings, and public conferences, all of which are held in a neutral manner to encourage open debate. The Institute’s Programs are divided into three areas: — Leadership Program offers educational and networking projects for outstanding young Central European professionals. Aspen Young Leaders Program brings together emerging and experienced leaders for four days of workshops, debates, and networking activities. — Policy Program enables expert discussions that support strategic think- ing and interdisciplinary approach in topics as digital agenda, cities’ de- velopment and creative placemaking, art & business, education, as well as transatlantic and Visegrad cooperation. -

November 14, 2019, Vol. 61, No. 46

El juicio político 12 Golpe en Bolivia 12 Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! workers.org Vol. 61 No. 46 Nov. 14, 2019 $1 U.S.-backed coup in Bolivia Indigenous, workers resist By John Catalinotto “opened the doors to absolute impu- Nov. 11—In a message from his base east of the country. Since Oct. 20, when nity for those who are able to exercise in the Chapare region in central Bolivia, Morales won re-election, these gangs have Nov. 12— From La Paz, journalist power.” But, Teruggi adds, “[The] half President Evo Morales said on the eve- attacked and beaten pro-Morales elected Marco Teruggi writes that 24 hours after of the country that voted for [President] ning of Nov. 10: “I want to tell you, broth- political leaders, burning their homes and the U.S.-backed coup in Bolivia, “There Evo Morales exists and will not stand ers and sisters, that the fight does not end offices across the country. is no formal government, but there is idly by.” Formal and informal organi- here. We will continue this fight for equal- Immediately, the imperialist-con- the power of arms.” (pagina12.org) zations of Indigenous peoples, campesi- ity, for peace.” (Al Jazeera, Nov. 11) trolled media worldwide tried to give Police and soldiers patrol at the behest nos and workers are blockading roads, Earlier that day, a fascist-led coup their unanimous spin to the event, slan- of the coup leaders, while fascistic gangs setting up self-defense units, and call- backed by the Bolivian police and mil- dering the Morales government and roam, beat and burn, the coup having ing for “general resistance to the coup itary, and receiving the full support of its Movement toward Socialism (MAS) d’état throughout the coun- U.S.