Political Realignment in Brazil: Jair Bolsonaro and the Right Turn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brazil: from a Global Example of Food Security to Back on the Hunger Map

Brazil: from a global example of food security to back on the Hunger Map Ariel Sepúlveda Sciences Po / PSIA Leaving the Hunger Map was a historical milestone in Brazilian politics, one that is currently under threat due to major cutbacks on social-economic policies in past years. The political instability, along with an economic crisis that the country faces has built the path to where it is now: with 10,3 mi people in food insecurity. This reveals a great contradiction, as Brazil allocates a large part of its food production for export, being the third-largest food producer in the world. In 2014, Brazil was commended internationally, for its great efforts in combating hunger and poverty. For the first time, the country was not featured on the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation’s (UN/FAO) Hunger Map, reducing food insecurity by 84% in 24 years. These promising numbers were a result of several food security policies, which improved food access, provided income generation, and supported food production by small farmers. Lula’s pink tide government Former President Lula in 2003, in the speech in which he launched Fome Zero. Photo: Ricardo Stuckert / Given the context of redemocratisation and decentralised social policies (Angell 1998), Luís Inácio Lula da Silva (Lula) of the Partido dos Trabalhadores – PT (Workers’ Party) chose the 1 politics around poverty and hunger as the central narrative of his candidature. When elected, he transformed the fight against hunger into a state obligation. The first and most famous policy was the Fome Zero (Zero Hunger), which was composed of cash grants, nutritional policies, and development projects that mobilised governmental and nongovernmental actors. -

CEPIK (2019) Brazilian Politics APR 17

BRAZILIAN POLITICS MARCO CEPIK - 2019 A. BACKGROUND 1822 - Independence from Portugal (September 07th) 1888 – Abolition of Slavery 1889 – Military Coup establishes the Old Republic 1930 – Vargas’ Revolution and Estado Novo 1945 – Military Coup establishes the Second Republic 1960 – New capital city Brasilia inaugurated 1964 – Military Coup and Authoritarian Regime 1985 – Indirect election establishes the New Republic 1988 – Current Federal Constitution (7th, 99 EC, 3/5 votes, twice, two houses) 1994 – Fernando Henrique Cardoso (PSDB) elected 1998 – Fernando Henrique Cardoso (PSDB) reelected 2002 – Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT) elected, his 4th time running 2006 – Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT) reelected (60.8% in the runoff) 2010 – Dilma Rousseff (PT) elected (56.05% in the runoff) 2014 – Dilma Rousseff (PT) reelected (51.64% in the runoff) 2015 – Second Wave of Protests (160 cities, 26 states, 3.6 m people) 2016 – 36th President Rousseff ousted in controversial Impeachment 2017 – Michel Temer (PMDB) as president: 76% in favor of resignation 2018 – Lula da Silva (PT) jailed / barred from running (April-August) 2018 – Jair Bolsonaro (PSL) elected in November (55.13% runoff) https://www.bbc.com/reel/playlist/what-happened-to-brazil ▸Area: 8,515,767 km2 (5th largest in the world, 47.3% of South America) ▸Population: 210.68 million (2019) ▸Brasilia: 04.29 million (2017), São Paulo is 21.09 million (metro area) ▸Whites 47.7 % Pardos 43.13 Blacks 7,6 Asians 1.09 Indigenous 0.4 ▸Religion 2010: 64.6% Catholic, 24% Protestant, 8% No religion ▸GDP -

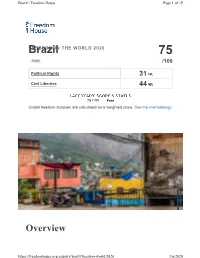

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Brazil | Freedom House Page 1 of 19 BrazilFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 75 FREE /100 Political Rights 31 Civil Liberties 44 75 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Brazil | Freedom House Page 2 of 19 Brazil is a democracy that holds competitive elections, and the political arena is characterized by vibrant public debate. However, independent journalists and civil society activists risk harassment and violent attack, and the government has struggled to address high rates of violent crime and disproportionate violence against and economic exclusion of minorities. Corruption is endemic at top levels, contributing to widespread disillusionment with traditional political parties. Societal discrimination and violence against LGBT+ people remains a serious problem. Key Developments in 2019 • In June, revelations emerged that Justice Minister Sérgio Moro, when he had served as a judge, colluded with federal prosecutors by offered advice on how to handle the corruption case against former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who was convicted of those charges in 2017. The Supreme Court later ruled that defendants could only be imprisoned after all appeals to higher courts had been exhausted, paving the way for Lula’s release from detention in November. • The legislature’s approval of a major pension reform in the fall marked a victory for Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was inaugurated in January after winning the 2018 election. It also signaled a return to the business of governing, following a period in which the executive and legislative branches were preoccupied with major corruption scandals and an impeachment process. -

Maria Da Penha

Global Feminisms Comparative Case Studies of Women’s Activism and Scholarship BRAZIL Maria da Penha Interviewer: Sueann Caulfield Fortaleza, Brazil February 2015 University of Michigan Institute for Research on Women and Gender 1136 Lane Hall Ann Arbor, MI 48109‐1290 Tel: (734) 764‐9537 E‐mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.umich.edu/~glblfem © Regents of the University of Michigan, 2015 Maria da Penha, born in 1945 in Fortaleza, Ceará, is a leader in the struggle against domestic violence in Brazil. Victimized by her husband in 1983, who twice tried to murder her and left her a paraplegic, she was the first to successfully bring a case of domestic violence to the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. It took years to bring the case to public attention. In 2001, the case resulted in the international condemnation of Brazil for neglect and for the systematic delays in the Brazilian justice system in cases of violence against women. Brazil was obliged to comply with certain recommendations, including a change to Brazilian law that would ensure the prevention and protection of women in situations of domestic violence and the punishment of the offender. The federal government, under President Lula da Silva, and in partnership with five NGOs and a number of important jurists, proposed a bill that was unanimously passed by both the House and the Senate. In 2006, Federal Law 11340 was ratified, known as the “Maria da Penha Law on Domestic and Family Violence.” Maria da Penha’s contribution to this important achievement for Brazilian women led her to receive significant honors, including "The Woman of Courage Award” from the United States in 2010.1 She also received the Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic from the Spanish Embassy, and in 2013, the Human Rights Award, which is considered the highest award of the Brazilian Government in the field of human rights. -

Tesis Doctoral: Salsa Y Década De Los Ochenta

PROGRAMA DE DOCTORADO EN MUSICOLOGÍA TESIS DOCTORAL: SALSA Y DÉCADA DE LOS OCHENTA. APROPIACIÓN, SUBJETIVIDAD E IDENTIDAD EN LOS PARTICIPANTES DE LA ESCENA SALSERA DE BOGOTÁ. Presentada por Bibiana Delgado Ordóñez para optar al grado de Doctora por la Universidad de Valladolid Dirigida por: Enrique Cámara de Landa Rubén López-Cano Secretaría Administrativa. Escuela de Doctorado. Casa del Estudiante. C/ Real de Burgos s/n. 47011-Valladolid. ESPAÑA Tfno.: + 34 983 184343; + 34 983 423908; + 34 983 186471 - Fax 983 186397 - E-mail: [email protected] Con respeto y admiración, a mi madre Aura Marina TABLA DE CONTENIDO Introducción .............................................................................................................................. 8 Capítulo I. Experiencia Estética en las Músicas Populares Urbanas ................................ 19 1.1. El artefacto cultural en el ejercicio de la estética .......................................................................................... 22 1.2. Subjetividades postmodernas y apropiación musical .................................................................................... 27 1.3. Identificaciones colectivas e individuales ..................................................................................................... 34 1.4. La construcción narrativa de la experiencia .................................................................................................. 38 1.5. El cuerpo en las músicas populares urbanas ................................................................................................ -

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations Updated July 6, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46236 SUMMARY R46236 Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations July 6, 2020 Occupying almost half of South America, Brazil is the fifth-largest and fifth-most-populous country in the world. Given its size and tremendous natural resources, Brazil has long had the Peter J. Meyer potential to become a world power and periodically has been the focal point of U.S. policy in Specialist in Latin Latin America. Brazil’s rise to prominence has been hindered, however, by uneven economic American Affairs performance and political instability. After a period of strong economic growth and increased international influence during the first decade of the 21st century, Brazil has struggled with a series of domestic crises in recent years. Since 2014, the country has experienced a deep recession, record-high homicide rate, and massive corruption scandal. Those combined crises contributed to the controversial impeachment and removal from office of President Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016). They also discredited much of Brazil’s political class, paving the way for right-wing populist Jair Bolsonaro to win the presidency in October 2018. Since taking office in January 2019, President Jair Bolsonaro has begun to implement economic and regulatory reforms favored by international investors and Brazilian businesses and has proposed hard-line security policies intended to reduce crime and violence. Rather than building a broad-based coalition to advance his agenda, however, Bolsonaro has sought to keep the electorate polarized and his political base mobilized by taking socially conservative stands on cultural issues and verbally attacking perceived enemies, such as the press, nongovernmental organizations, and other branches of government. -

Venezuela: Un Equilibrio Inestable

REVISTA DE CIENCIA POLÍTICA / VOLUMEN 39 / N° 2 / 2019 / 391-408 VENEZUELA: AN UNSTABLE EQUILIBRIUM Venezuela: un equilibrio inestable DIMITRIS PANTOULAS IESA Business School, Venezuela JENNIFER MCCOY Georgia State University, USA ABSTRACT Venezuela’s descent into the abyss deepened in 2018. Half of the country’s GDP has been lost in the last five years; poverty and income inequality have deepened, erasing the previous gains from the earlier years of the Bolivarian Revolution. Sig- nificant economic reforms failed to contain the hyperinflation, and emigration ac- celerated to reach three million people between 2014 and 2018, ten percent of the population. Politically, the government of Nicolás Maduro completed its authorita- rian turn following the failed Santo Domingo dialogue in February, and called for an early election in May 2018. Maduro’s victory amidst a partial opposition boycott and international condemnation set the stage for a major constitutional clash in January 2019, when the world was divided between acknowledging Maduro’s se- cond term or an opposition-declared interim president, Juan Guaido. Key words: Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro, economic crisis, hyperinflation, elections, electoral legitimacy, authoritarianism, polarization RESUMEN El descenso de Venezuela en el abismo se profundizó en 2018. La mitad del PIB se perdió en los últimos cinco años; la pobreza y la desigualdad de ingresos se profundizaron, anulando los avances de los primeros años de la Revolución Bolivariana. Las importantes reformas económicas no lograron contener la hiperinflación y la emigración se aceleró para llegar a tres millones de personas entre 2014 y 2018, el diez por ciento de la población. Políticamen- te, el gobierno de Nicolás Maduro completó su giro autoritario luego del fracasado proceso de diálogo de Santo Domingo en febrero, y Maduro pidió una elección adelantada en mayo de 2018. -

Casaroes the First Y

LATIN AMERICA AND THE NEW GLOBAL ORDER GLOBAL THE NEW AND AMERICA LATIN Antonella Mori Do, C. Quoditia dium hucient. Ur, P. Si pericon senatus et is aa. vivignatque prid di publici factem moltodions prem virmili LATIN AMERICA AND patus et publin tem es ius haleri effrem. Nos consultus hiliam tabem nes? Acit, eorsus, ut videferem hos morei pecur que Founded in 1934, ISPI is THE NEW GLOBAL ORDER an independent think tank alicae audampe ctatum mortanti, consint essenda chuidem Dangers and Opportunities committed to the study of se num ute es condamdit nicepes tistrei tem unum rem et international political and ductam et; nunihilin Itam medo, nondem rebus. But gra? in a Multipolar World economic dynamics. Iri consuli, ut C. me estravo cchilnem mac viri, quastrum It is the only Italian Institute re et in se in hinam dic ili poraverdin temulabem ducibun edited by Antonella Mori – and one of the very few in iquondam audactum pero, se issoltum, nequam mo et, introduction by Paolo Magri Europe – to combine research et vivigna, ad cultorum. Dum P. Sp. At fuides dermandam, activities with a significant mihilin gultum faci pro, us, unum urbit? Ublicon tem commitment to training, events, Romnit pari pest prorimis. Satquem nos ta nostratil vid and global risk analysis for pultis num, quonsuliciae nost intus verio vis cem consulicis, companies and institutions. nos intenatiam atum inventi liconsulvit, convoliis me ISPI favours an interdisciplinary and policy-oriented approach perfes confecturiae audemus, Pala quam cumus, obsent, made possible by a research quituam pesis. Am, quam nocae num et L. Ad inatisulic team of over 50 analysts and tam opubliciam achum is. -

Redalyc.Participation in Democratic Brazil: from Popular Hegemony And

Opinião Pública E-ISSN: 1807-0191 [email protected] Universidade Estadual de Campinas Brasil Avritzer, Leonardo Participation in democratic Brazil: from popular hegemony and innovation to middle-class protest Opinião Pública, vol. 23, núm. 1, abril, 2017, pp. 43-59 Universidade Estadual de Campinas São Paulo, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=32950439002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Participation in democratic Brazil: from popular hegemony and innovation to middle-class protest Leonardo Avritzer Introduction Democracy has had historically different patterns of collective action (Tilly, 1986, 2007; Tarrow, 1996). Repertoires of collective action are a routine of processes of negotiation and struggle between the state and social actors (Tilly, 1986, p. 4). Each political era has a repertoire of collective action or protest that is related to many variables, among them the form of organization of the state; the form of organization of production; and the technological means available to social actors. Early eighteenth- century France experienced roadblocks as a major form of collective action (Tilly, 1986). Late nineteenth-century France had already seen the development of other repertoires, such as the city mobilization that became famous in Paris and led to the re-organization of the city’s urban spaces (Tarrow, 1996, p. 138-139). At the same time that the French blocked roads and occupied cities, the Americans used associations and large demonstrations (Skocpol, 2001; Verba et al., 1994) to voice claims concerning the state. -

Constitutional Change in Brazil: Political and Financial Decentralisation, 1981-1991

CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE IN BRAZIL: POLITICAL AND FINANCIAL DECENTRALISATION, 1981-1991 Celina Maria de Souza Motta The London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Government Thesis submitted for a Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1995 UMI Number: U615788 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615788 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I S F 72SS ^V om \C ^ x'cS )07&zzs% Abstract The aim of the present study is to investigate how and why a country facing issues that needed to be tackled nationwide chose to decentralise political power and financial resources when it moved from military rule to redemocratisation. Furthermore, the study examines whether the decision to decentralise taken in Brazil in the period 1981-1991 has changed the allocation of public expenditure at sub-national level, especially to education. By analysing the decision to decentralise and its results at the sub-national level, the study embodies both an upstream and a downstream approach. The upstream approach encompasses the topics related to decentralisation in the Brazilian Constituent National Assembly that sat from 1987 to 1988. -

China News Digest March 30, 2019 Contents

China News Digest March 30, 2019 Contents Latest news .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 01 China Says It’s Willing to Seek Trade, Investment Deals With Brazil ..................................................................................... 01 China’s Belt and Road Gets a Win in Italy ............................................................................................................................................ 02 US-China soy trade war could destroy 13 million hectares of rainforest ............................................................................ 03 China Takes on U.S. Over Venezuela After Russia Sends Troops: It’s Not Your ‘Backyard’ ......................................... 04 Finance Meeting in China Canceled Over Venezuela Dispute, Sources Say ......................................................................... 05 Bolsonaro gets Trump’s praise but few concessions, riling Brazilians ................................................................................... 06 Brazil’s Guedes Says Country will Trade with Both U.S. and China ..........................................................................................07 Recent background ............................................................................................................................................................................ 08 China acknowledges Latin American human -

Cuba Rebecca Bodenheimer

Cuba Rebecca Bodenheimer LAST MODIFIED: 26 MAY 2016 DOI: 10.1093/OBO/97801997578240184 Introduction This article treats folkloric and popular musics in Cuba; literature on classical music will be included in the article entitled “Classical Music in Cuba.” Music has long been a primary signifier of Cuban identity, both on and off the island. Among small nations, Cuba is almost unparalleled in its global musical reach, an influence that dates back to the international dissemination of the contradanza and habanera in the 19th century. The 1930s constituted a crucial decade of Cuban musical influence, as the world was introduced to the genre son (mislabeled internationally as “rumba”/”rhumba”) with the hit song “El Manicero.” In the 1990s Cuban music underwent yet another international renaissance, due to both the emergence of a neotraditional style of son related to the success of the Buena Vista Social Club project, and the crystallization of a new style of Cuban dance music called timba. Moreover, Afro Cuban folkloric music has enjoyed increased visibility and attention, and has become a focal point of the tourism industry that the Castro regime began to expand as a response to the devastating economic crisis precipitated by the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Research on Cuban music has a long and distinguished history that began in earnest in the late 1920s and 1930s with the publications of Cuba’s most celebrated scholar, Fernando Ortiz. Many of Ortiz’s students, such as musicologist Argeliers León and folklorist Miguel Barnet, went on to form the backbone of Cuban folklore research after the Revolution in 1959.