Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Ecumenism*?

What is Ecumenism*? From the Greek meaning “inhabited house.” A worldwide movement among Christians who accept Jesus as Lord and savior and, inspired by the Holy Spirit, seek through prayer, dialogue, and other initiatives to eliminate barriers and move toward the unity Christ willed for his church (Jn 17:21; see also Eph 4:4-5, UR 1-4). Christian communities separated over the Council of Ephesus (431), over the Council of Chalcedon (451), through the East-West schism conventionally dated 1054, at the Reformation in the sixteenth century, and later. Vatican II taught that the true church “subsists in” but is not simply identified with the Catholic Church (LG 8). Belief in Christ and baptism establish a real, if imperfect, union among all Christians (LG 15). In particular, the Orthodox share with Catholics very many elements of faith and sacramental life, including the Eucharist and apostolic succession (see OE 27-30). The Church Unity Octave, eight days of prayer for religious unity of all Christians, which is celebrated each year from January 17 to 25, was stared in 1908 by the founder of the Society of Atonement, Fr. Paul Wattson (1863-1940) when still a member of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States. The following year, with other friars, sisters, and laymen of his Graymoor community, he was received into the Catholic Church * From A Concise Dictionary of Theology. Eds. Gerald O’Collins, S.J. and Edward Farrugia, S.J. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2000. What is Interreligious Dialogue? First, interreligious dialogue can be described as a kind of “formal conversation” with persons of non- Christian faiths. -

An Ecumenical Journey

An Ecumenical Journey A timeline of the World Council of Churches The Netherlands 1948 Zimbabwe 1998 USA 1954 Canada 1983 Sweden 1968 Australia 1991 India 1961 Kenya 1975 Brazil 2006 General Secretaries of WCC W. A. Visser ’t Hooft (1900-1985) Philip Potter (1921-) Konrad Raiser (1938-) Olav Fykse Tveit (1960-) Term: 1938-1966 Term: 1972-1985 Term: 1993-2003 Term: 2010- A brilliant and visionary Christian leader from the A Methodist pastor, missionary and youth leader from A German theologian who served on the WCC staff under A pastor from the Lutheran communion, Tveit began his Netherlands, Willem Visser ’t Hooft was named WCC general Dominica in the West Indies, Potter was called to several Philip Potter, Raiser once described his ecumenical calling as term of office in January 2010 following seven years as secretary at the 1938 meeting in which the WCC’s process of positions in the WCC. During his mandate as general “a second conversion.” During a sometimes turbulent period leader of the Church of Norway’s council on ecumenical formation began. A Reformed minister, he emphasized the secretary, he insisted on the fundamental unity of Christian for the ecumenical movement, he led the Council as general and international relations. Bringing wide experience in importance of linking the ecumenical movement to enduring witness and Christian service and the correlation of faith secretary in a redefinition of its “Common Understanding inter-religious dialogue, Tveit had also served as co-chair manifestations of the church through the ages. In 1968 he and action. and Vision” and in a fundamental review of the participation of the Palestine Israel Ecumenical Forum core group was elected honorary president of the WCC by the fourth of Orthodox member churches. -

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa was consecrated as the Roman Catholic Diocesan Bishop of Botucatu in Brazil on December !" #$%&" until certain views he expressed about the treatment of the Brazil’s poor, by both the civil (overnment and the Roman Catholic Church in Brazil caused his removal from the Diocese of Botucatu. His Excellency was subsequently named as punishment as *itular bishop of Maurensi by the late Pope Pius +, of the Roman Catholic Church in #$-.. His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord Carlos Duarte Costa had been a strong advocate in the #$-0s for the reform of the Roman Catholic Church" he challenged many of the 1ey issues such as • Divorce" • challenged mandatory celibacy for the clergy, and publicly stated his contempt re(arding. 2*his is not a theological point" but a disciplinary one 3 Even at this moment in time in an interview with 4ermany's Die 6eit magazine the current Bishop of Rome" Pope Francis is considering allowing married priests as was in the old time including lets not forget married bishops and we could quote many Bishops" Cardinals and Popes over the centurys prior to 8atican ,, who was married. • abuses of papal power, including the concept of Papal ,nfallibility, which the bishop considered a mis(uided and false dogma. His Excellency President 4et9lio Dornelles 8argas as1ed the Holy :ee of Rome for the removal of His Excellency Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa from the Diocese of Botucatu. *he 8atican could not do this directly. 1 | P a g e *herefore the Apostolic Nuncio to Brazil entered into an agreement with the :ecretary of the Diocese of Botucatu to obtain the resi(nation of His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord. -

A Pope of Their Own

Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church UPPSALA STUDIES IN CHURCH HISTORY 1 About the series Uppsala Studies in Church History is a series that is published in the Department of Theology, Uppsala University. The series includes works in both English and Swedish. The volumes are available open-access and only published in digital form. For a list of available titles, see end of the book. About the author Magnus Lundberg is Professor of Church and Mission Studies and Acting Professor of Church History at Uppsala University. He specializes in early modern and modern church and mission history with focus on colonial Latin America. Among his monographs are Mission and Ecstasy: Contemplative Women and Salvation in Colonial Spanish America and the Philippines (2015) and Church Life between the Metropolitan and the Local: Parishes, Parishioners and Parish Priests in Seventeenth-Century Mexico (2011). Personal web site: www.magnuslundberg.net Uppsala Studies in Church History 1 Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church Lundberg, Magnus. A Pope of Their Own: Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church. Uppsala Studies in Church History 1.Uppsala: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, 2017. ISBN 978-91-984129-0-1 Editor’s address: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, Church History, Box 511, SE-751 20 UPPSALA, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]. Contents Preface 1 1. Introduction 11 The Religio-Political Context 12 Early Apparitions at El Palmar de Troya 15 Clemente Domínguez and Manuel Alonso 19 2. -

40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4T

VERBUM ic Biblical Federation I I I I I } i V \ 40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4t BULLETIN DEI VERBUM is a quarterly publica tion in English, French, German and Spanish. Editors Alexander M. Schweitzer Glaudio EttI Assistant to the editors Dorothea Knabe Production and layout bm-projekte, 70771 Leinf.-Echterdingen A subscription for one year consists of four issues beginning the quarter payment is Dei Verbum Congress 2005 received. Please indicate in which language you wish to receive the BULLETIN DEI VERBUM. Summary Subscription rates ■ Ordinary subscription: US$ 201 €20 ■ Supporting subscription: US$ 34 / € 34 Audience Granted by Pope Benedict XVI « Third World countries: US$ 14 / € 14 ■ Students: US$ 14/€ 14 Message of the Holy Father Air mail delivery: US$ 7 / € 7 extra In order to cover production costs we recom mend a supporting subscription. For mem Solemn Opening bers of the Catholic Biblical Federation the The Word of God In the Life of the Church subscription fee is included in the annual membership fee. Greeting Address by the CBF President Msgr. Vincenzo Paglia 6 Banking details General Secretariat "Ut Dei Verbum currat" (Address as indicated below) LIGA Bank, Stuttgart Opening Address of the Exhibition by the CBF General Secretary A l e x a n d e r M . S c h w e i t z e r 1 1 Account No. 64 59 820 IBAN-No. DE 28 7509 0300 0006 4598 20 BIO Code GENODEF1M05 Or per check to the General Secretariat. -

The Holy See (Including Vatican City State)

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE EVALUATION OF ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING MEASURES AND THE FINANCING OF TERRORISM (MONEYVAL) MONEYVAL(2012)17 Mutual Evaluation Report Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism THE HOLY SEE (INCLUDING VATICAN CITY STATE) 4 July 2012 The Holy See (including Vatican City State) is evaluated by MONEYVAL pursuant to Resolution CM/Res(2011)5 of the Committee of Ministers of 6 April 2011. This evaluation was conducted by MONEYVAL and the report was adopted as a third round mutual evaluation report at its 39 th Plenary (Strasbourg, 2-6 July 2012). © [2012] Committee of experts on the evaluation of anti-money laundering measures and the financing of terrorism (MONEYVAL). All rights reserved. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. For any use for commercial purposes, no part of this publication may be translated, reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic (CD-Rom, Internet, etc) or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the MONEYVAL Secretariat, Directorate General of Human Rights and Rule of Law, Council of Europe (F-67075 Strasbourg or [email protected] ). 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PREFACE AND SCOPE OF EVALUATION............................................................................................ 5 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................................... -

The Promise of the New Ecumenical Directory

Theological Studies Faculty Works Theological Studies 1994 The Promise of the New Ecumenical Directory Thomas P. Rausch Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/theo_fac Part of the Catholic Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rausch, Thomas P. “The Promise of the New Ecumenical Directory,” Mid-Stream 33 (1994): 275-288. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theological Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas P. Rausch The Promise of the ew Ecumenical Directory Thomas P. Rausch, S. J., is Professor of Theological Studies and Rector of the Jesuit Community at Loyola Marym01.1nt University, Los Angeles, California, and chair of the department. A specialist in the areas of ecclesiology, ecumenism, and the theology of the priesthood, he is the author of five books and numerous articles. he new Roman Catholic Ecumenical Directory (ED), officially titled the Directory for the Application ofPrinciples and Norms on Ecumenism, was released on June 8, 1993 by the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. 1 In announcing it, Pope John Paul II said that its preparation was motivated by "the desire to hasten the journey towards unity, an indispensable condition for a truly re newed evangelization. "2 The pope's linking of Christian unity with a renewal of the Church's work of evangelization is important, for the very witness of the Church as a community of humankind reconciled in Christ is weakened by the obvious lack of unity among Christians. -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC JOURNEY OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI TO BRAZIL ON THE OCCASION OF THE FIFTH GENERAL CONFERENCE OF THE BISHOPS OF LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN MEETING AND CELEBRATION OF VESPERS WITH THE BISHOPS OF BRAZIL ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI Catedral da Sé, São Paulo Friday, 11 May 2007 Dear Brother Bishops! "Although he was the Son of God, he learned obedience through what he suffered; and being made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation to all who obey him." (cf. Heb 5:8-9). 1. The text we have just heard in the Lesson for Vespers contains a profound teaching. Once again we realize that God’s word is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword; it penetrates to the depths of the soul and it grants solace and inspiration to his faithful servants (cf. Heb 4:12). I thank God for the opportunity to be with this distinguished Episcopate, which presides over one of the largest Catholic populations in the world. I greet you with a sense of deep communion and sincere affection, well aware of your devotion to the communities entrusted to your care. The warm reception given to me by the Rector of the Catedral da Sé and by all present has made me feel at home in this great common House which is our Holy Mother, the Catholic Church. 2 I extend a special greeting to the new Officers of the National Conference of Brazilian Bishops and, with gratitude for the kind words of its President, Archbishop Geraldo Lyrio Rocha, I offer prayerful good wishes for his work in deepening communion among the Bishops and in promoting common pastoral activity in a territory of continental dimensions. -

Solidarity and Mediation in the French Stream Of

SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Timothy R. Gabrielli Dayton, Ohio December 2014 SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. APPROVED BY: _________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Anthony J. Godzieba, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Timothy R. Gabrielli All rights reserved 2014 iii ABSTRACT SOLIDARITY MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. In its analysis of mystical body of Christ theology in the twentieth century, this dissertation identifies three major streams of mystical body theology operative in the early part of the century: the Roman, the German-Romantic, and the French-Social- Liturgical. Delineating these three streams of mystical body theology sheds light on the diversity of scholarly positions concerning the heritage of mystical body theology, on its mid twentieth-century recession, as well as on Pope Pius XII’s 1943 encyclical, Mystici Corporis Christi, which enshrined “mystical body of Christ” in Catholic magisterial teaching. Further, it links the work of Virgil Michel and Louis-Marie Chauvet, two scholars remote from each other on several fronts, in the long, winding French stream. -

The 18Th International Congress of Jesuit Ecumenists”

“The 18th International Congress of Jesuit Ecumenists” ................................................................. 2 “Conversion to Interreligious Dialogue.....”, James T. Bretzke, S.J. ................................................. 2 “The Practice of Daoist (Taoist) Compassion”, Michael Saso, S.J. .................................................. 3 “Kehilla, Church and Jewish people”, David Neuhaus, S.J. ............................................................. 6 “Let us Cross Over the Other Shore”, Christophe Ravanel, S.J. ………………………………….….10 “Six Theses on Islam in Europe”, Groupe des Deux Rives……………………………………….11 “Meeting of Jesuits in Islamic Studies, September 2006” .............................................................. 13 “Encounter and the Risk of Change”, Wilfried Dettling, S.J. ......................................................... 14 Secretariat for Interreligious Dialogue; Curia S.J., C.P. 6139, 00195 Roma Prati, Italy; N.11 tel. (39) 06.689.77.567/8; fax: 06.689.77.580; e-mail: [email protected] 2006 4 Vatican II, through the conceptual revolution THE 18TH INTERNATIONAL in ecumenical appreciation produced by CONGRESS OF Unitatis Redintegratio, and into the more JESUIT ECUMENISTS recent involvement of Jesuits in the ecumenical movement since the time of the Second Vatican Council. Edward Farrugia The Jesuit Ecumenists are an informal group looks at a specific issue that lies at the heart of Jesuit scholars active in the movement for of Catholic-Orthodox relations, that of the Christian unity who have -

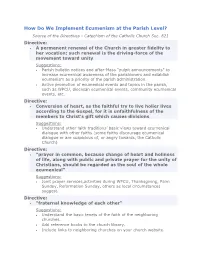

How Do We Implement Ecumenism at the Parish Level? Source of the Directives - Catechism of the Catholic Church Sec

How Do We Implement Ecumenism at the Parish Level? Source of the Directives - Catechism of the Catholic Church Sec. 821 Directive: A permanent renewal of the Church in greater fidelity to her vocation; such renewal is the driving-force of the movement toward unity Suggestions: Parish bulletin notices and after-Mass "pulpit announcements" to increase ecumenical awareness of the parishioners and establish ecumenism as a priority of the parish administration. Active promotion of ecumenical events and topics in the parish, such as WPCU, diocesan ecumenical events, community ecumenical events, etc. Directive: Conversion of heart, as the faithful try to live holier lives according to the Gospel, for it is unfaithfulness of the members to Christ's gift which causes divisions Suggestions: Understand other faith traditions’ basic views toward ecumenical dialogue with other faiths (some faiths discourage ecumenical dialogue or are suspicious of, or angry towards, the Catholic Church) Directive: "prayer in common, because change of heart and holiness of life, along with public and private prayer for the unity of Christians, should be regarded as the soul of the whole ecumenical" Suggestions: Joint prayer services,activities during WPCU, Thanksgiving, Palm Sunday, Reformation Sunday, others as local circumstances suggest. Directive: "fraternal knowledge of each other" Suggestions: Understand the basic tenets of the faith of the neighboring churches. Add reference books to the church library. Include links to neighboring churches on your church website. Directive: "ecumenical formation, of the faithful and especially of priests" Suggestions: For larger parishes, form an ecumenical and interreligious commission. For smaller parishes, appoint an appropriate person as the ecumenical & interfaith liaison. -

The Concept of “Sister Churches” in Catholic-Orthodox Relations Since

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA The Concept of “Sister Churches” In Catholic-Orthodox Relations since Vatican II A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Will T. Cohen Washington, D.C. 2010 The Concept of “Sister Churches” In Catholic-Orthodox Relations since Vatican II Will T. Cohen, Ph.D. Director: Paul McPartlan, D.Phil. Closely associated with Catholic-Orthodox rapprochement in the latter half of the 20 th century was the emergence of the expression “sister churches” used in various ways across the confessional division. Patriarch Athenagoras first employed it in this context in a letter in 1962 to Cardinal Bea of the Vatican Secretariat for the Promotion of Christian Unity, and soon it had become standard currency in the bilateral dialogue. Yet today the expression is rarely invoked by Catholic or Orthodox officials in their ecclesial communications. As the Polish Catholic theologian Waclaw Hryniewicz was led to say in 2002, “This term…has now fallen into disgrace.” This dissertation traces the rise and fall of the expression “sister churches” in modern Catholic-Orthodox relations and argues for its rehabilitation as a means by which both Catholic West and Orthodox East may avoid certain ecclesiological imbalances toward which each respectively tends in its separation from the other. Catholics who oppose saying that the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church are sisters, or that the church of Rome is one among several patriarchal sister churches, generally fear that if either of those things were true, the unicity of the Church would be compromised and the Roman primacy rendered ineffective.