Article Reviews Walter Kasper on the Catholic Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4T

VERBUM ic Biblical Federation I I I I I } i V \ 40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4t BULLETIN DEI VERBUM is a quarterly publica tion in English, French, German and Spanish. Editors Alexander M. Schweitzer Glaudio EttI Assistant to the editors Dorothea Knabe Production and layout bm-projekte, 70771 Leinf.-Echterdingen A subscription for one year consists of four issues beginning the quarter payment is Dei Verbum Congress 2005 received. Please indicate in which language you wish to receive the BULLETIN DEI VERBUM. Summary Subscription rates ■ Ordinary subscription: US$ 201 €20 ■ Supporting subscription: US$ 34 / € 34 Audience Granted by Pope Benedict XVI « Third World countries: US$ 14 / € 14 ■ Students: US$ 14/€ 14 Message of the Holy Father Air mail delivery: US$ 7 / € 7 extra In order to cover production costs we recom mend a supporting subscription. For mem Solemn Opening bers of the Catholic Biblical Federation the The Word of God In the Life of the Church subscription fee is included in the annual membership fee. Greeting Address by the CBF President Msgr. Vincenzo Paglia 6 Banking details General Secretariat "Ut Dei Verbum currat" (Address as indicated below) LIGA Bank, Stuttgart Opening Address of the Exhibition by the CBF General Secretary A l e x a n d e r M . S c h w e i t z e r 1 1 Account No. 64 59 820 IBAN-No. DE 28 7509 0300 0006 4598 20 BIO Code GENODEF1M05 Or per check to the General Secretariat. -

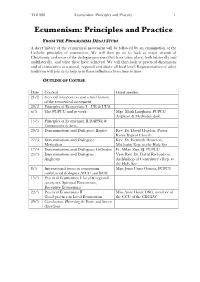

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

This Article First Presents the Status Questionis of the Issue of Communion for the Remarried Divorcees

EUCHARISTIC COMMUNION FOR THE REMARRIED D IVORCEES: IS AMORIS LAETITIA THE FINAL ANSWER? RAMON D. ECHICA This article first presents the status questionis of the issue of communion for the remarried divorcees. There is an interlocution between the affirmative answer represented by Walter Kasper and the negative answer represented by Carlo Caffara and Gerhard Mueller. The article then offers two theological concepts not explicitly mentioned in Amoris Laetitia to buttress the affirmative answer. INTRODUCTION THE CONTEXT OF THE ISSUE rom the Synod of the Family of 2014, then followed by a bigger Fsynod on the same subject a year after, up to the issuance of the Apostolic Exhortation Amoris Laetitia (AL), what got the most media attention was the issue of the reception of Eucharistic communion by divorcees, whose marriages have never been declared null by the Church and who have entered a second (this time purely civil or state) marriage. The issue became the subject matter of some reasoned theological discourse but also of numerous acrimonious debates. Three German bishops, namely Walter Kasper, Karl Lehman and Oskar Saier were the first prominent hierarchical members who openly raised the issue through a pastoral letter in 1993.1Nothing much came out of it until Pope Francis signaled his 1 Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger thumbed down the proposal in 1994. For a brief history of the earlier attempts to allow divorcees to receive communion, see Lisa Duffy, “Pope Benedict Already Settled the Question of Communion for the Hapág 13, No. 1-2 (2016) 49-69 EUCHARISTIC COMMUNION FOR THE REMARRIED DIVORCESS openness to rethink the issue. -

Oblates to Celebrate Life of Mother Mary Lange,Special Care Collection

Oblates to celebrate life of Mother Mary Lange More than 30 years before the Emancipation Proclamation, Mother Mary Lange fought to establish the first religious order for black women and the first black Catholic school in the United States. To honor the 126th anniversary of their founder’s death, the Oblate Sisters of Providence have planned a Feb. 3 Mass of Thanksgiving at 1 p.m., which will be celebrated by Cardinal William H. Keeler in the Our Lady of Mount Providence Convent Chapel in Catonsville. The Mass will be followed by a reception, offering guests the opportunity to view Mother Mary Lange memorabilia. A novena will also be held Jan. 25-Feb. 2 in the chapel. Sister M. Virginie Fish, O.S.P., and several of her colleagues in the Archdiocese of Baltimore have devoted nearly 20 years to working on the cause of canonization for Mother Mary Lange, who, along with Father James Hector Joubert, S.S., founded the Oblate Sisters in 1829. With the help of two other black women, Mother Mary Lange also founded St. Frances Academy, Baltimore, in 1828, which is the first black Catholic school in the country and still in existence. Sister Virginie said the sisters see honoring Mother Mary Lange as a fitting way to kick-start National Black History Month. Father John Bowen, S.S., postulator for Mother Mary Lange’s cause, completed the canonization application three years ago and sent it to Rome, where it is currently under review. There is no timetable for the Vatican to complete or reject sainthood for Mother Mary Lange, Father Bowen said. -

Bishop Celebrates 50Th Anniversary Mass at Marian High School

September 21, 2014 Think Green 50¢ Recycle Volume 88, No. 30 Go Green todayscatholicnews.org Serving the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend Go Digital ’’ RED MASS OPEN TO TTODAYODAYSS CCATHOLICATHOLIC ALL THE FAITHFUL A Red Mass will be held Wednesday, Sept. 24, at 5:30 p.m. Bishop celebrates 50th anniversary at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Fort Wayne. The South Bend area Mass at Marian High School Red Mass will be Monday, Oct. 6, at 5:15 p.m. at the BY CHRISTOPHER LUSHIS Basilica of the Sacred Heart MISHAWAKA — “Put out into the See pages 13-14 deep!” announced Bishop Kevin C. Rhoades to the Marian High School community during their golden anni- versary Mass on Sept. 4. This joyous occasion commemorated the com- Tribute pletion of the endeavor undertaken by the sixth bishop of the Diocese Father Chrobot dies of Fort Wayne-South Bend, Bishop Leo A. Pursley, to construct a sec- Page 3 ond Catholic high school to serve the needs of the South Bend and Mishawaka area in 1964. Present for this special Mass Congregation were Benedictine Father Jonathan Fassero, a member of the first gradu- of Holy Cross ating class of 1968 from Marian, and Msgr. Michael Heintz, rector of Six make final vows, St. Matthew Cathedral and a 1985 graduate. Also in attendance were ordained deacons priests from St. Jude, St. Anthony de KEVIN HAGGENJOS Page 5 Padua, St. Bavo, St. Matthew and St. th Thomas Parishes, as well as priests Bishop Kevin C. Rhoades celebrates Mass on Thursday, Sept. -

Philadelphia Meeting, Synods Will Be Part of Debate on Families

The CatholicWitness The Newspaper of the Diocese of Harrisburg September 26, 2014 Vol. 48 No. 18 CHRIS HEISEY, THE CATHOLIC WITNESS The colors of Hispanic heritage filled St. Patrick Cathedral and the steps of the state Capitol in Harrisburg Sept. 14 for the Diocesan Hispanic Heritage Mass. The celebration displayed the culture and gifts of Hispanic Catholics, and marked the 70th anniversary of ministry to Spanish-speaking Catholics in the diocese. See cover- age of the Mass and the Hispanic Apostolate on pages 8 and 9. Philadelphia Meeting, Synods Will be Part of Debate on Families By Francis X. Rocca Pope Francis has said both synods will con- Catholic News Service sider, among other topics, the eligibility of divorced and civilly remarried Catholics to The World Meeting of Families in Phila- receive Communion, whose predicament he delphia in September 2015 will serve as a has said exemplifies a general need for mercy forum for debating issues on the agenda for in the church today. the world Synod of Bishops at the Vatican the “We’re bringing up all the issues that would following month, said the two archbishops re- have appeared in the preparation documents sponsible for planning the Philadelphia event. for the synod as part of our reflection,” said At a Sept. 16 briefing, Archbishop Vincen- Archbishop Charles J. Chaput of Philadel- zo Paglia, president of the Pontifical Council phia, regarding plans for the world meeting. for the Family, described the world meeting “I can’t imagine that any of the presenters as one of several related events to follow the won’t pay close attention to what’s happen- October 2014 extraordinary Synod of Bishops ing” in Rome. -

Mercy Is a Person: Pope Francis and the Christological Turn in Moral Theology

Journal of Moral Theology, Vol. 6, No. 2 (2017): 48-69 Mercy Is a Person: Pope Francis and the Christological Turn in Moral Theology Alessandro Rovati Before all else, the Gospel invites us to respond to the God of love who saves us, to see God in others and to go forth from ourselves to seek the good of others. […] If this invitation does not radiate forcefully and attractively, the edifice of the Church’s moral teaching risks becoming a house of cards, and this is our greatest risk. It would mean that it is not the Gospel which is being preached, but certain doctrinal or moral points based on specific ideological options. The message will run the risk of losing its freshness and will cease to have ‘the fragrance of the Gospel’ (Evangelii Gaudium, no. 39). HESE WORDS FROM THE APOSTOLIC Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium represent one of the main concerns of Francis’s pontificate, namely, the desire to call the Church back to the heart of the Gospel message so that her preaching may not T 1 be distorted or reduced to some of its secondary aspects. Francis put it strongly in the famous interview he released to his Jesuit brother Antonio Spadaro, “The Church’s pastoral ministry cannot be obsessed with the transmission of a disjointed multitude of doctrines to be imposed insistently. Proclamation in a missionary style focuses on the essentials, on the necessary things: this is also what fascinates and attracts more, what makes the heart burn. … The proposal of the gospel must be more simple, profound, radiant. -

Association of Catholic Publishers • News Release

Association of Catholic Publishers • News Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Therese Brown, [email protected] May 18, 2016 Mercy Dominates as Theme of 2016 ACP Excellence in Publishing Awards Binz Wins Two Awards in Two Different Categories Liturgical Press Is Publisher of the 2016 “Book of the Year” BALTIMORE, MD — The Association of Catholic Publishers (ACP) is pleased to announce the winners of the new Excellence in Publishing Awards, which will be given out at the 20th Annual Catholic Marketing Network International Trade Show in Schaumburg, Illinois. The goal of these awards is to recognize the best in Catholic publishing. “In the midst of this Year of Mercy, it is not surprising to see winners that focus on mercy and kindness explicitly,” stated Therese Brown, executive director of the Association of Catholic Publishers. “What is truly interesting are the number of award-winning titles that illustrate those traits in the lives of “saints,” some canonized and others not.” The 2016 “Book of the Year” is To Be One in Christ by Edward P. Hahnenberg from Liturgical Press. “This book will be very helpful for a Church called to embrace multicultural, multiethnic and multilingual issues that face pastoral ministers,” commented one of the judges. “With an in-depth examination of theological, cultural, sociological, and ecumenical perspectives, this book will be a useful companion for pastors, parish life, and all in pastoral formation. This book should be required reading for all pastors and those in seminary formation.” The “Book of the Year” is selected from among the first-place finishers. Liturgical Press walks away with 6 awards including 3 first place finishers and the Book of the Year. -

May 19, 2008 T H E N a T I O N a L C a T H O L I C W E E K L Y $2.75

May 19, 2008AmericaTHE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WEEKLY $2.75 OW QUICKLY the Information into a mass of factoids and infomercials Age has been eclipsed by on the latest must-have products. instantaneous infotainment. I What stimulated this frustrated rant of America have been a newshound all my mine is the loss of hard news, especially Published by Jesuits of the United States Hlife; but despite the multiplicity of outlets, on the cable networks. Cable news cover- hard news is becoming increasingly diffi- age of the presidential campaign is Editor in Chief cult for me to find. The dearth of real enough to make me long for C-Span on- Drew Christiansen, S.J. news on the ever-transforming media the-road videos of Senator Joe Biden giv- platforms is painful to endure. Years ago, ing a long-winded speech to Iowa farm- Acting Publisher as a new subscriber to AOL, I tracked the ers at a county fair. Given the looming James Martin, S.J. collapse of the Soviet Union, the breakup problems the country faces, this year’s of the former Yugoslavia and the election is the most important in at least Managing Editor Oklahoma City bombing. But today what a generation. But instead of serious Robert C. Collins, S.J. passes for a news home page at that Web reporting—and I realize how boring it portal is cluttered with celebrity teasers can be riding in the back of a campaign Business Manager and consumer advice. bus, as the Baltimore Sun’s Jack Lisa Pope To find the news, even when there is Germond used to do—what the viewer Editorial Director an item listed on the home page that I gets is talking heads revisiting the same would like to pull up, requires digging tired, manufactured issues night after Karen Sue Smith several layers deep. -

"There Is a Threeness About You": Trinitarian Images of God, Self, and Community Among Medieval Women Visionaries Donna E

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-31-2011 "There is a Threeness About You": Trinitarian Images of God, Self, and Community Among Medieval Women Visionaries Donna E. Ray Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation Ray, Donna E.. ""There is a Threeness About You": Trinitarian Images of God, Self, and Community Among Medieval Women Visionaries." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/65 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THERE IS A THREENESS ABOUT YOU”: TRINITARIAN IMAGES OF GOD, SELF, AND COMMUNITY AMONG MEDIEVAL WOMEN VISIONARIES BY DONNA E. RAY B.A., English and Biblical Studies, Wheaton College (Ill.), 1988 M.A., English, Northwestern University, 1992 M.Div., Princeton Theological Seminary, 1995 S.T.M., Yale University, 1999 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2011 ©2011, Donna E. Ray iii DEDICATION For Harry iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Timothy Graham, Dr. Nancy McLoughlin, Dr. Anita Obermeier, and Dr. Jane Slaughter, for their valuable recommendations pertaining to this study and assistance in my professional development. I am also grateful to fellow members of the Medieval Latin Reading Group at the UNM Institute for Medieval Studies (Yulia Mikhailova, Kate Meyers, and James Dory-Garduño, under the direction of Dr. -

Pope Benedict XVI - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 13

Pope Benedict XVI - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 13 Pope Benedict XVI From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI (in Latin Benedictus XVI) Benedict XVI was born Joseph Alois Ratzinger on April 16, 1927. He is the 265th and current Pope, the bishop of Rome and head of the Roman Catholic Church. He was elected on April 19, 2005, in the 2005 papal conclave, over which he presided. He was formally inaugurated during the papal inauguration Mass on April 24, 2005. Contents 1 Overview 2 Early life (1927–1951) 2.1 Background and childhood (1927–1943) 2.2 Military service (1943–1945) 2.3 Education (1946–1951) 3 Early church career (1951–1981) 4 Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (1981 - 2005) 4.1 Health 4.2 Sex abuse scandal Name Joseph Alois Ratzinger 4.3 Dialogue with other faiths Papacy began April 19, 2005 5 Papacy 5.1 Election to the Papacy Papacy ended Incumbent 5.1.1 Prediction Predecessor Pope John Paul II 5.1.2 Election Successor Incumbent 5.2 Choice of name Born April 16, 1927 5.3 Early days of Papacy Place of birth Marktl am Inn, Bavaria, 6 See also Germany 7 Notes 8 Literature 9 Works 10 See also 11 External links and references 11.1 Official 11.2 Biographical 11.3 General Overview Pope Benedict was elected at the age of 78, the oldest pope since Clement XII (elected 1730) at the start of his papacy. He served longer as a cardinal before being elected pope than any pope since Benedict XIII (elected 1724). -

How Does the Holy Spirit Assist the Church in Its Teaching?

THE DUQUESNE UNIVERSITY EIGHTH ANNUAL HOLY SPIRIT LECTURE How Does the Holy Spirit Assist the Church in Its Teaching? January 31, 2014 Duquesne Union Ballroom Pittsburgh, PA Featuring Special Guest Dr. Richard R. Gaillardetz The Joseph Professor of Catholic Systematic Theology, Boston College President of the Catholic Theological Society of America 2 The Spirit in the New Millennium: “The Spirit in the New Millennium: The Duquesne University Annual Holy Spirit Lecture and Colloquium” was initiated in 2005 by Duquesne University President Charles J. Dougherty as an expression of Duquesne’s mission and charism as a university both founded by the Congregation of the Holy Spirit and dedicated to the Holy Spirit. It is hoped that this ongoing series of lectures and accompanying colloquia will encourage the exploration of ideas pertaining to the theology of the Holy Spirit. Besides fostering scholarship on the Holy Spirit within an ecumenical context, this event is intended to heighten awareness of how pneumatology (the study of the Spirit) might be relevantly integrated into the various academic disciplines in general. A video recording of the lecture, as well as the present text may be accessed online at www.duq.edu/holyspirit. You can contact us at [email protected]. Radu Bordeianu, Ph.D., serves as the director. 2 1 2013 Colloquists • Dr. Radu Bordeianu Associate Professor of Theology, Duquesne University • Dr. Peter C. Bouteneff Associate Professor in Systematic Theology and Director of Institutional Assessment, St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary • Dr. Lynn H. Cohick Professor of New Testament, Wheaton College • Dr. Brian P. Flanagan Assistant Professor of Theology, Marymount University • Dr.