Christian Witness in Interreligious Context. I Am Deeply Grateful to Prof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sedevacantists and Una Cum Masses

Dedicated to Patrick Henry Omlor The Grain of Incense: Sedevacantists and Una Cum Masses — Rev. Anthony Cekada — www.traditionalmass.org Should we assist at traditional Masses offered “together with Thy servant Benedict, our Pope”? articulate any theological reasons or arguments for “Do not allow your tongue to give utterance to what your heart knows is not true.… To say Amen is to what he does. subscribe to the truth.” He has read or heard the stories of countless early — St. Augustine, on the Canon martyrs who chose horrible deaths, rather than offer even one grain of incense in tribute to the false, ecu- “Our charity is untruthful because it is not severe; menical religion of the Roman emperor. So better to and it is unpersuasive, because it is not truthful… Where there is no hatred of heresy, there is no holi- avoid altogether the Masses of priests who, through ness.” the una cum, offer a grain of incense to the heresiarch — Father Faber, The Precious Blood Ratzinger and his false ecumenical religion… In many parts of the world, however, the only tra- IN OUR LIVES as traditional Catholics, we make many ditional Latin Mass available may be one offered by a judgments that must inevitably produce logical conse- priest (Motu, SSPX or independent) who puts the false quences in our actual religious practice. The earliest pope’s name in the Canon. Faced with choosing this or that I remember making occurred at about age 14. Gui- nothing, a sedevacantist is then sometimes tempted to tar songs at Mass, I concluded, were irreverent. -

Spiritan Missionaries: Precursors of Inculturation Theology

Spiritan Horizons Volume 14 Issue 14 Article 13 Fall 2019 Spiritan Missionaries: Precursors of Inculturation Theology Bede Uche Ukwuije Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/spiritan-horizons Part of the Catholic Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ukwuije, B. U. (2019). Spiritan Missionaries: Precursors of Inculturation Theology. Spiritan Horizons, 14 (14). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/spiritan-horizons/vol14/iss14/13 This Soundings is brought to you for free and open access by the Spiritan Collection at Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spiritan Horizons by an authorized editor of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. Bede Uche Ukwuije, C.S.Sp. Spiritan Missionaries as Precursors of Inculturation Theology in West Africa: With Particular Reference to the Translation of Church Documents into Vernacular Languages 1 Bede Uche Ukwuije, C.S.Sp. Introduction Bede Uche Ukwuije, C.S.Sp., is Recent studies based on documents available in the First Assistant to the Superior archives of missionary congregations have helped to arrive General and member of the at a positive appreciation of the contribution of the early Theological Commission of the missionaries to the development of African cultures.2 This Union of Superiors General, Rome. He holds a Doctorate presentation will center on the work done by Spiritans in in Theology (Th.D.) from some West African countries, especially in the production the Institut Catholique de of dictionaries and grammar books and the translation of Paris and a Ph.D. in Theology the Bible and church documents into vernacular languages. and Religious Studies from Contrary to the widespread idea that the early missionaries the Catholic University of destroyed African cultures (the tabula rasa theory), this Leuven, Belgium. -

4. Inculturation in Moral Theology-JULIAN SALDANHA

Julian Saldanha, SJ Inculturation in moral theology Fr. Julian Saldanha, SJ ([email protected]) other branches of theology, moral theology holds a Doctorate in Missiology. He lectures has been very tardy in undertaking at St. Pius College, Mumbai and in several inculturation. Furthermore, even twenty years theological Institutes in India. He serves on after Vatican II, moral theology in India had the editorial board of "Mission Today" and remained tied to canonical and philosophical- "Mission Documentation". He was President ethical ways of thinking.1 It was found "to be of the ecumenical "Fellowship of Indian weighed down, among other things, by Missiologists" and continues to be active in paternalism, legalism and individualism". 2 the field of inter-religious dialogue. He wrote One reason for the general tardiness may be the Basic Text for the First Asian Mission that inculturation in this field is very Congress (2006) held in Thailand and helped challenging and difficult; it can also prove as a resource person there. In this article he quite controversial. All the same, it is argues forcefully for inculturation in moral incumbent on moral theologians to render this theology. service to the local church. It is much easier to purvey/impose on the young churches a 1. A Necessary Task readymade moral theology elaborated in a The task of inculturation in moral theology Western context. Questions and problems is part of the inculturation of theology in arising from the 'Third Church' of the general. It is a task which was laid on the Southern hemisphere hardly figured in the 'young churches' by Vatican II. -

40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4T

VERBUM ic Biblical Federation I I I I I } i V \ 40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4t BULLETIN DEI VERBUM is a quarterly publica tion in English, French, German and Spanish. Editors Alexander M. Schweitzer Glaudio EttI Assistant to the editors Dorothea Knabe Production and layout bm-projekte, 70771 Leinf.-Echterdingen A subscription for one year consists of four issues beginning the quarter payment is Dei Verbum Congress 2005 received. Please indicate in which language you wish to receive the BULLETIN DEI VERBUM. Summary Subscription rates ■ Ordinary subscription: US$ 201 €20 ■ Supporting subscription: US$ 34 / € 34 Audience Granted by Pope Benedict XVI « Third World countries: US$ 14 / € 14 ■ Students: US$ 14/€ 14 Message of the Holy Father Air mail delivery: US$ 7 / € 7 extra In order to cover production costs we recom mend a supporting subscription. For mem Solemn Opening bers of the Catholic Biblical Federation the The Word of God In the Life of the Church subscription fee is included in the annual membership fee. Greeting Address by the CBF President Msgr. Vincenzo Paglia 6 Banking details General Secretariat "Ut Dei Verbum currat" (Address as indicated below) LIGA Bank, Stuttgart Opening Address of the Exhibition by the CBF General Secretary A l e x a n d e r M . S c h w e i t z e r 1 1 Account No. 64 59 820 IBAN-No. DE 28 7509 0300 0006 4598 20 BIO Code GENODEF1M05 Or per check to the General Secretariat. -

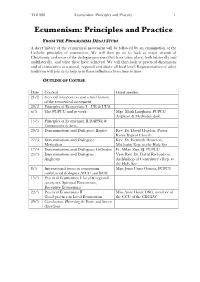

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

Is Feeneyism Catholic? / François Laisney

I S F That there is only one true Church, the one, Holy, Catholic, EENEYISM Apostolic, and Roman Church, outside of which no one can be saved, has always been taught by the Catholic Church. This dogma, however, has been under attack in recent times. Already last century, the Popes had to repeatedly rebuke the liberal Catholics for their tendency to dilute this The Catholic dogma, “reducing it to a meaningless formula.” But in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s, the same dogma was C Meaning of misrepresented on the opposite side by Fr. Feeney ATHOLIC and his followers, changing “outside the Church there is The Dogma, no salvation” into “without water baptism there is absolutely no salvation,” thereby denying doctrines which had been “Outside the positively and unanimously taught by the Church, that is, Baptism of Blood and Baptism of Desire. ? Catholic Church IS FEENEYISM REV. FR. FRANÇOIS LAISNEY There Is No CATHOLIC? Salvation” What is at stake?—Fidelity to the unchangeable Catholic Faith, to the Tradition of the Church. We must neither deviate on the left nor on the right. The teaching Church must “religiously guard and faithfully explain the deposit of Faith that was handed down through the Apostles,…this apostolic doctrine that all the Fathers held, and the holy orthodox Doctors reverenced and followed” (Vatican I); all members of the Church must receive that same doctrine, without picking and choosing what they will believe. We may not deny a point of doctrine that belongs to the IS deposit of Faith—though not yet defined—under the pretext that it has been distorted by the Liberals. -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC LETTER ORIENTALE LUMEN OF THE SUPREME PONTIFF JOHN PAUL II TO THE BISHOPS, CLERGY AND FAITHFUL TO MARK THE CENTENARY OF ORIENTALIUM DIGNITAS OF POPE LEO XIII Venerable Brothers, Dear Sons and Daughters of the Church 1. The light of the East has illumined the universal Church, from the moment when "a rising sun" appeared above us (Lk 1:78): Jesus Christ, our Lord, whom all Christians invoke as the Redeemer of man and the hope of the world. That light inspired my predecessor Pope Leo XIII to write the Apostolic Letter Orientalium Dignitas in which he sought to safeguard the significance of the Eastern traditions for the whole Church.(1) On the centenary of that event and of the initiatives the Pontiff intended at that time as an aid to restoring unity with all the Christians of the East, I wish to send to the Catholic Church a similar appeal, which has been enriched by the knowledge and interchange which has taken place over the past century. Since, in fact, we believe that the venerable and ancient tradition of the Eastern Churches is an integral part of the heritage of Christ's Church, the first need for Catholics is to be familiar with that tradition, so as to be nourished by it and to encourage the process of unity in the best way possible for each. Our Eastern Catholic brothers and sisters are very conscious of being the living bearers of this 2 tradition, together with our Orthodox brothers and sisters. The members of the Catholic Church of the Latin tradition must also be fully acquainted with this treasure and thus feel, with the Pope, a passionate longing that the full manifestation of the Church's catholicity be restored to the Church and to the world, expressed not by a single tradition, and still less by one community in opposition to the other; and that we too may be granted a full taste of the divinely revealed and undivided heritage of the universal Church(2) which is preserved and grows in the life of the Churches of the East as in those of the West. -

Inculturation of the Liturgy in Local Churches: Case of the Diocese of Saint Thomas, U.S

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online School of Divinity Master’s Theses and Projects Saint Paul Seminary School of Divinity Winter 12-2014 Inculturation of the Liturgy in Local Churches: Case of the Diocese of Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands Touchard Tignoua Goula University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/sod_mat Part of the History Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Tignoua Goula, Touchard, "Inculturation of the Liturgy in Local Churches: Case of the Diocese of Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands" (2014). School of Divinity Master’s Theses and Projects. 8. https://ir.stthomas.edu/sod_mat/8 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Saint Paul Seminary School of Divinity at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Divinity Master’s Theses and Projects by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SAINT PAUL SEMINARY SCHOOL OF DIVINITY UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS Inculturation of the Liturgy in Local Churches: Case of the Diocese of Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands A THESIS Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Divinity Of the University of St. Thomas In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Master of Arts in Theology © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Touchard Tignoua Goula St. Paul, MN 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS General Introduction..……………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter one: The Jewish Roots of Christian Liturgy……………….……………………..2 A. -

The Challenge of the Roman Catholic Church in South America During The

The Mission Wesley Khristopher Teixeira Alves Spring, 2007 DESCRIPTION OF THE MOVIE- THE MISSION The challenge facing the Roman Catholic Church in South America during the Spanish and Portuguese colonization showed in the movie The Mission was not an easy one: the priests had to have strong faith and dedicate time, work, knowledge and their own lives so that the indigenous pagans could reach God. These ministers were sent to the South American colonies in midst of the chaos that was happening in Europe in consequence of the Protestant Reformation of Calvin, Henry VIII, and Luther. The Roman Catholic Church reacted against the Protestant Reformation with the work of leaders like Saint Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the order of Jesuits. Many of these Jesuits were sent to the New World to convert American gentiles (the Indians of South America) to the doctrines and traditions of the Catholic Church. (Klaiber, 2004) The Mission is set in the eighteenth century, in South America. The film has as one of its main characters a violent native-slave merchant named Rodrigo Mendoza (played by Robert DeNiro), who regrets the murder of his brother. After that, this mercenary carries out a self-penitence and ends up converting himself as a missioner Jesuit in Sete Povos das Missões (a region of South America claimed by both Portuguese and Spanish nations). This was the stage of the Guerras Guaraníticas, which was the war between indigenous people supported by the Jesuits against Empire Colonizers and slave mercenaries. The Mission won the Golden palm award in Cannes and the Oscar for cinematography. -

Mortally Sinful Media!

Spiritual information you must know to be saved Mortally sinful media! “Know also this, that, in the last days, shall come dangerous times. Men shall be lovers of themselves, covetous, haughty, proud, blasphemers, disobedient to parents, ungrateful, wicked, without affection, without peace, slanderers, incontinent, unmerciful, without kindness, Traitors, stubborn, puffed up, and lovers of pleasures more than of God: Having an appearance indeed of godliness, but denying the power thereof. Now these avoid.” (2 Timothy 3:1-5) Most people of this generation, even those who profess themselves Christian, are so fallen away in morals that even the debauched people who lived a hundred years ago would be ashamed of the many things people today enjoy. And this is exactly what the devil had planned from the start, to step by step lowering the standard of morality in the world through the media until, in fact, one cannot escape to sin mortally by watching it with the intention of enjoying oneself. Yes to watch ungodly media only for enjoyment or pleasure or for to waste time (which could be used for God), as most people do, is mortally sinful. 54 years ago (1956), Elvis Presley had to be filmed above the waist up on a tv-show because of a hip-swiveling movement. Not that it was an acceptable performance, everything tending to sexuality is an abomination, but still it serves to prove how much the decline has come since then, when even the secular press deemed inappropriate what today would be looked upon as nothing. But even at that time, in major Hollywood films like The Ten Commandments, could be seen both women and men that are incredibly immodestly dressed. -

Article Reviews Walter Kasper on the Catholic Church

ecclesiology 14 (2018) 203-211 ECCLESIOLOGY brill.com/ecso Article Reviews ∵ Walter Kasper on the Catholic Church Susan K. Wood Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, usa [email protected] Walter Kasper The Catholic Church: Nature, Reality and Mission, trans. Thomas Hoebel (London and New York: Bloomsbury, T&T Clark, 2015), xviii + 463 pp. isbn 978-1-4411-8709-3 (pbk). $54.95. The Catholic Church: Nature – Reality – Mission, following more than twenty years after Jesus the Christ and The God of Jesus Christ, is the third volume of a trilogy, their Christological unity indicated by their German titles: Jesus Der Christus (1974), Der Gott Jesu Christi (1982) and Die Kirche Jesu Christi (2008). Life had intervened in the interim, first by Kasper’s service as bishop of Rottenburg- Stuttgart (1989–1999), followed by eleven years with the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity (1999–2010) where he was its cardinal prefect from 2001. This interim period also included his work as theological secretary of the Extraordinary Synod (1985) which had identified communio as a central theme and guiding principle of the Second Vatican Council. His life in and for the church had interrupted his theological work on a systematic treatise on the church, fortuitous for an ecclesiology that not only reflects develop- ment since the Second Vatican Council, but also aims to be an existential ec- clesiology relevant for both the individual and society. He comments that an ecclesiology for today must perceive the crisis of the Church manifested by decreasing church attendance, decline in participation in the sacraments, and priest shortages in connection with the crises of today’s world in a post- Constantinian time (p. -

This Article First Presents the Status Questionis of the Issue of Communion for the Remarried Divorcees

EUCHARISTIC COMMUNION FOR THE REMARRIED D IVORCEES: IS AMORIS LAETITIA THE FINAL ANSWER? RAMON D. ECHICA This article first presents the status questionis of the issue of communion for the remarried divorcees. There is an interlocution between the affirmative answer represented by Walter Kasper and the negative answer represented by Carlo Caffara and Gerhard Mueller. The article then offers two theological concepts not explicitly mentioned in Amoris Laetitia to buttress the affirmative answer. INTRODUCTION THE CONTEXT OF THE ISSUE rom the Synod of the Family of 2014, then followed by a bigger Fsynod on the same subject a year after, up to the issuance of the Apostolic Exhortation Amoris Laetitia (AL), what got the most media attention was the issue of the reception of Eucharistic communion by divorcees, whose marriages have never been declared null by the Church and who have entered a second (this time purely civil or state) marriage. The issue became the subject matter of some reasoned theological discourse but also of numerous acrimonious debates. Three German bishops, namely Walter Kasper, Karl Lehman and Oskar Saier were the first prominent hierarchical members who openly raised the issue through a pastoral letter in 1993.1Nothing much came out of it until Pope Francis signaled his 1 Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger thumbed down the proposal in 1994. For a brief history of the earlier attempts to allow divorcees to receive communion, see Lisa Duffy, “Pope Benedict Already Settled the Question of Communion for the Hapág 13, No. 1-2 (2016) 49-69 EUCHARISTIC COMMUNION FOR THE REMARRIED DIVORCESS openness to rethink the issue.