Toward a Renewed Theology and Practice of Confirmation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constantia, St

THE AGES DIGITAL LIBRARY REFERENCE CYCLOPEDIA of BIBLICAL, THEOLOGICAL and ECCLESIASTICAL LITERATURE Constantia, St. - Czechowitzky, Martin by James Strong & John McClintock To the Students of the Words, Works and Ways of God: Welcome to the AGES Digital Library. We trust your experience with this and other volumes in the Library fulfills our motto and vision which is our commitment to you: MAKING THE WORDS OF THE WISE AVAILABLE TO ALL — INEXPENSIVELY. AGES Software Rio, WI USA Version 1.0 © 2000 2 Constantia, Saint a martyr at Nuceria, under Nero, is commemorated September 19 in Usuard's Martyrology. Constantianus, Saint abbot and recluse, was born in Auvergne in the beginning of the 6th century, and died A.D. 570. He is commemorated December 1 (Le Cointe, Ann. Eccl. Fran. 1:398, 863). Constantin, Boniface a French theologian, belonging to the Jesuit order, was born at Magni (near Geneva) in 1590, was professor of rhetoric and philosophy at Lyons, and died at Vienne, Dauphine, November 8, 1651. He wrote, Vie de Cl. de Granger Eveque et Prince dae Geneve (Lyons, 1640): — Historiae Sanctorum Angelorum Epitome (ibid. 1652), a singular work upon the history of angels. He also-wrote some other works on theology. See Hoefer, Nouv. Biog. Generale, s.v.; Jocher, Allgemeines Gelehrten- Lexikon, s.v. Constantine (or Constantius), Saint is represented as a bishop, whose deposition occurred at Gap, in France. He is commemorated April 12 (Gallia Christiana 1:454). SEE CONSTANTINIUS. Constantine Of Constantinople deacon and chartophylax of the metropolitan Church of Constantinople, lived before the 8th century. There is a MS. -

Stages of Papal Law

Journal of the British Academy, 5, 37–59. DOI https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/005.037 Posted 00 March 2017. © The British Academy 2017 Stages of papal law Raleigh Lecture on History read 1 November 2016 DAVID L. D’AVRAY Fellow of the British Academy Abstract: Papal law is known from the late 4th century (Siricius). There was demand for decretals and they were collected in private collections from the 5th century on. Charlemagne’s Admonitio generalis made papal legislation even better known and the Pseudo-Isidorian collections brought genuine decretals also to the wide audience that these partly forged collections reached. The papal reforms from the 11th century on gave rise to a new burst of papal decretals, and collections of them, culminating in the Liber Extra of 1234. The Council of Trent opened a new phase. The ‘Congregation of the Council’, set up to apply Trent’s non-dogmatic decrees, became a new source of papal law. Finally, in 1917, nearly a millennium and a half of papal law was codified by Cardinal Gasparri within two covers. Papal law was to a great extent ‘demand- driven’, which requires explanation. The theory proposed here is that Catholic Christianity was composed of a multitude of subsystems, not planned centrally and each with an evolving life of its own. Subsystems frequently interfered with the life of other subsystems, creating new entanglements. This constantly renewed complexity had the function (though not the purpose) of creating and recreating demand for papal law to sort out the entanglements between subsystems. For various reasons other religious systems have not generated the same demand: because the state plays a ‘papal’ role, or because the units are small, discrete and simple, or thanks to a clear simple blueprint, or because of conservatism combined with a tolerance of some inconsistency. -

Faith Statement Outline

Sample/Draft Faith Statement Outline God’s “Yes” and My “Yes” - Confirming My Faith Pray about what God wants you to say your Faith Statement Your talk should be 5 - 7 minutes in length. Prayerfully consider ways to incorporate your chosen Confirmation Bible verse into your Faith Statement. 1. Introduction a. Introduce yourself by sharing your name and school, and anything else about you that you think would be helpful. b. Begin with a short prayer thanking God for this opportunity to share your faith and asking God for the ability to speak from your heart. 2. What do you believe about our Triune God – Father, Son and Holy Spirit? a. Share what it is that you believe about God the Father, Jesus and the Holy Spirit. b. Share your understanding that God first said “yes” to you - claiming you in baptism and connecting you to Jesus’ death and resurrection. c. Share why you choose to say “yes” to our Triune God. 3. How has faith in Jesus Christ impacted your daily life? a. Explain how/why a living and active faith in Jesus Christ has been, and is, important to you. b. How has your relationship with Jesus impacted your relationships with friends and family? c. How has the presence of God made a difference in your life at school, church, work or family? 4. How has faith in Jesus carried you through the hard times in your life? a. Share how your faith in Christ has helped to keep you strong when the storms and temptations have confronted you? b. -

Western Illuminated Manuscripts: a Catalogue of the Collection in Cambridge University Library Paul Binski and Patrick Zutshi Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-84892-3 - Western Illuminated Manuscripts: A Catalogue of the Collection in Cambridge University Library Paul Binski and Patrick Zutshi Frontmatter More information WESTERN ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS Cambridge University Library’s collection of illuminated manuscripts is of international signifi cance. It originates in the medieval university and stands alongside the holdings of the Colleges and the Fitzwilliam Museum. Th e University Library contains major European examples of medieval illumination from the ninth to the sixteenth centuries, with acknowledged masterpieces of Romanesque, Gothic and Renaissance book art, as well as illuminated literary texts, including the fi rst complete Chaucer manuscript. Th is catalogue provides scholars and researchers easy access to the University Library’s illuminated manuscripts, evaluating the importance of many of them for the very fi rst time. It contains descriptions of famous manuscripts – for example, the Life of Edward the Confessor attributed to Matthew Paris – as well as hundreds of lesser-known items. Beautifully illustrated throughout, the catalogue contains descriptions of individual manuscripts with up-to-date assessments of their style, origins and importance, together with bibliographical references. PAUL BINSKI is Professor of the History of Medieval Art at Cambridge University. He specializes in the art and architecture of medieval Western Europe. His previous publications include Th e Painted Chamber at Westminster (1986), Westminster Abbey and the Plantagenets (1995), which won the Longman History Today Book of the Year award, and Becket’s Crown: Art and Imagination in Gothic England, 1170–1300 (2004), winner of the 2006 Historians of British Art Prize and the Ace-Mercers 2005 International Book Prize. -

40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4T

VERBUM ic Biblical Federation I I I I I } i V \ 40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4t BULLETIN DEI VERBUM is a quarterly publica tion in English, French, German and Spanish. Editors Alexander M. Schweitzer Glaudio EttI Assistant to the editors Dorothea Knabe Production and layout bm-projekte, 70771 Leinf.-Echterdingen A subscription for one year consists of four issues beginning the quarter payment is Dei Verbum Congress 2005 received. Please indicate in which language you wish to receive the BULLETIN DEI VERBUM. Summary Subscription rates ■ Ordinary subscription: US$ 201 €20 ■ Supporting subscription: US$ 34 / € 34 Audience Granted by Pope Benedict XVI « Third World countries: US$ 14 / € 14 ■ Students: US$ 14/€ 14 Message of the Holy Father Air mail delivery: US$ 7 / € 7 extra In order to cover production costs we recom mend a supporting subscription. For mem Solemn Opening bers of the Catholic Biblical Federation the The Word of God In the Life of the Church subscription fee is included in the annual membership fee. Greeting Address by the CBF President Msgr. Vincenzo Paglia 6 Banking details General Secretariat "Ut Dei Verbum currat" (Address as indicated below) LIGA Bank, Stuttgart Opening Address of the Exhibition by the CBF General Secretary A l e x a n d e r M . S c h w e i t z e r 1 1 Account No. 64 59 820 IBAN-No. DE 28 7509 0300 0006 4598 20 BIO Code GENODEF1M05 Or per check to the General Secretariat. -

The Sacrament of Confirmation

St. Anthony 1 St. Cecilia 1 St. Margaret-St. John EASTSIDE PASTORAL REGION THE SACRAMENT OF CONFIRMATION SPONSOR GUIDE CONTENTS PART 1 An Introduction to Becoming a Confirmation Sponsor 1 Chapter 1: What is Confirmation? 1 Chapter 2: What is a Sponsor? 3 Chapter 3: How Can I Help My Candidate Prepare for the Sacrament? 6 PART 2 Four Important Conversations to Have with Your Candidate 11 Phase 1: “The Way” — On the Road to Discovering Christ 12 Phase 2: “The Truth” — Encountering the Light of Christ 14 Phase 3: “The Life” — Choosing Ultimate Happiness 16 Phase 4: Mystagogy — Life After Confirmation 18 PART 3 Top Ten Catholic Questions 21 PART 4 Tools and Tidbits to Aid Sponsors 29 “Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of God belongs to such as these.” – Mark 10:14 WELCOME! You have been invited to sponsor a candidate for Confirmation, an invitation of great honor and responsibility. A “sponsor” is not just an honorary title; it is a calling. Your candidate has identified you as a living witness of faith in Jesus Christ and His Church. With this honor comes the responsibility to guide and support your candidate as he or she prepares for the Sacrament of Confirmation and beyond. You are called to be a Christian witness, friend, prayer warrior, and ally to your candidate for the rest of your life. You may have questions and perhaps even some hesitations about your role as sponsor. This guide will help you become an effective sponsor by renewing and encouraging your personal growth in Catholic faith and life. -

DOV Confirmation Study Guide Seven Sacraments: Beatitudes

DOV Confirmation Study Guide Seven Sacraments: Beatitudes: Sacraments of Initiation Blessed are the poor in spirit, the kingdom of Baptism heaven is theirs. Confirmation Blessed are they who mourn, they will be Eucharist comforted. Sacraments of Healing Blessed are the meek, they will inherit the earth. Reconciliation Blessed are they who hunger and thirst for Anointing of the Sick righteousness, they will be satisfied. Sacraments of Vocations Blessed are the merciful, they will be shown Matrimony mercy. Holy Orders Blessed are the clean of heart, they will see God. Blessed are the peacemakers, they will be called Two Great Commandments: children of God. 1. You shall love the Lord your God with all your Blessed are they who are persecuted for the sake heart, with all your soul, with all your mind, of righteousness, the kingdom of heaven is theirs. and with all your strength. 2. You shall love your neighbor as yourself. Four Marks of the Catholic Church: ● One ● Holy ● Catholic ● Apostolic Twelve Apostles: 1. Peter 7. John Holy Days of Obligation: 2. Bartholomew 8. Jude 3. Andrew 9. Philip Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God (Jan. 1 4. Matthew 10. Simon Ascension (40 days after Easter) 5. James 11. Thomas Assumption of Mary (August 15) 6. James the Less 12. Judas All Saints Day (November 1) Ten Commandments: Immaculate Conception (December 8) Christmas (December 25) 1. I am the Lord your God: you shall not have strange gods before me. 2. You shall not take the name of the Lord, your God, Cardinal Virtues: in vain. 3. Remember to keep holy the Lord's day. -

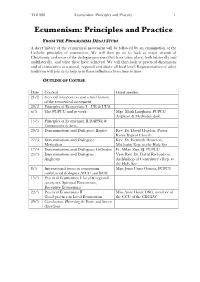

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

Globalization and Orthodox Christianity: a Glocal Perspective

religions Article Globalization and Orthodox Christianity: A Glocal Perspective Marco Guglielmi Human Rights Centre, University of Padua, Via Martiri della Libertà, 2, 35137 Padova, Italy; [email protected] Received: 14 June 2018; Accepted: 10 July 2018; Published: 12 July 2018 Abstract: This article analyses the topic of Globalization and Orthodox Christianity. Starting with Victor Roudometof’s work (2014b) dedicated to this subject, the author’s views are compared with some of the main research of social scientists on the subject of sociological theory and Eastern Orthodoxy. The article essentially has a twofold aim. Our intention will be to explore this new area of research and to examine its value in the study of this religion and, secondly, to further investigate the theory of religious glocalization and to advocate the fertility of Roudometof’s model of four glocalizations in current social scientific debate on Orthodox Christianity. Keywords: Orthodox Christianity; Globalization; Glocal Religions; Eastern Orthodoxy and Modernity Starting in the second half of the nineteen-nineties, the principal social scientific studies that have investigated the relationship between Orthodox Christianity and democracy have adopted the well-known paradigm of the ‘clash of civilizations’ (Huntington 1996). Other sociological research projects concerning religion, on the other hand, have focused on changes occurring in this religious tradition in modernity, mainly adopting the paradigm of secularization (in this regard see Fokas 2012). Finally, another path of research, which has attempted to develop a non-Eurocentric vision, has used the paradigm of multiple modernities (Eisenstadt 2000). In his work Globalization and Orthodox Christianity (2014b), Victor Roudometof moves away from these perspectives. -

Balthasar Hubmaier and the Authority of the Church Fathers

Balthasar Hubmaier and the Authority of the Church Fathers ANDREW P. KLAGER In Anabaptist historical scholarship, the reluctance to investigate the authority of the church fathers for individual sixteenth-century Anabaptist leaders does not appear to be intentional. Indeed, more pressing issues of a historiographical and even apologetical nature have been a justifiable priority, 1 and soon this provisional Anabaptist vision was augmented by studies assessing the possibility of various medieval chronological antecedents. 2 However, in response to Kenneth Davis’ important study, Anabaptism and Asceticism , Peter Erb rightly observed back in 1976 that “. one must not fail to review the abiding influence of the Fathers . [whose] monitions were much more familiar to our sixteenth-century ancestors than they are to us.” 3 Over thirty years later, the Anabaptist community still awaits its first published comprehensive study of the reception of the church fathers among Anabaptist leaders in the sixteenth century. 4 A natural place to start, however, is the only doctor of theology in the Anabaptist movement, Balthasar Hubmaier. In the final analysis, it becomes evident that Hubmaier does view the church fathers as authoritative, contextually understood, for some theological issues that were important to him, notably his anthropology and understanding of the freedom of the will, while he acknowledged the value of the church fathers for the corollary of free will, that is, believers’ baptism, and this for apologetico-historical purposes. This authority, however, cannot be confused with an untested, blind conformity to prescribed precepts because such a definition of authority did not exist in the sixteenth-century, even among the strongest Historical Papers 2008: Canadian Society of Church History 134 Balthasar Hubmaier admirers of the fathers. -

“Here I Stand” — the Reformation in Germany And

Here I Stand The Reformation in Germany and Switzerland Donald E. Knebel January 22, 2017 Slide 1 1. Later this year will be the 500th anniversary of the activities of Martin Luther that gave rise to what became the Protestant Reformation. 2. Today, we will look at those activities and what followed in Germany and Switzerland until about 1555. 3. We will pay particular attention to Luther, but will also talk about other leaders of the Reformation, including Zwingli and Calvin. Slide 2 1. By 1500, the Renaissance was well underway in Italy and the Church was taking advantage of the extraordinary artistic talent coming out of Florence. 2. In 1499, a 24-year old Michelangelo had completed his famous Pietà, commissioned by a French cardinal for his burial chapel. Slide 3 1. In 1506, the Church began rebuilding St. Peter’s Basilica into the magnificent structure it is today. 2. To help pay for such masterpieces, the Church had become a huge commercial enterprise, needing a lot of money. 3. In 1476, Pope Sixtus IV had created a new market for indulgences by “permit[ing] the living to buy and apply indulgences to deceased loved ones assumed to be suffering in purgatory for unrepented sins.” Ozment, The Age of Reform: 1250-1550 at 217. 4. By the time Leo X became Pope in 1513, “it is estimated that there were some two thousand marketable Church jobs, which were literally sold over the counter at the Vatican; even a cardinal’s hat might go to the highest bidder.” Bokenkotter, A Concise History of the Catholic Church at 198. -

Anglican-Lutheran Cycle of Prayer

An Anglican – Lutheran Cycle of Prayer 29 Nov 2009 to 28 Nov 2010 29 Nov 2009 ACC The Members of the Anglican Church of Canada ELCIC The Members of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada 6 Dec 2009 ACC Archbishop Fred Hiltz, Primate, Archdeacon Paul Feheley and the staff of the Primate’s Office ELCIC National Bishop Susan Johnson and the staff of the National Office 13 Dec 2009 ACC Archdeacon Michael Pollesel, General Secretary of the Anglican Church of Canada, and his staff ELCIC Trina Gallop, Director of Communications and Stewardship, and her staff 20 Dec 2009 ACC Dr. Eileen Scully, Interim Director of Faith, Worship and Ministry, and staff ELCIC Pastor Paul Johnson, Assistant to the National Bishop 27 Dec 2009 ACC Mr Vianney (Sam) Carriere, Director of Communications and Information Resources, and his staff, and also Michele George, Treasurer, and Director of Financial Management, and her staff ELCIC Pastor Paul Gehrs, Assistant to the National Bishop 3 Jan 2010 ACC Bishop Mark MacDonald, National Indigenous Anglican Bishop, and the Anglican Council of Indigenous People ELCIC Bishop Michael Pryse and the people and rostered ministers of the Eastern Synod 10 Jan 2010 ACC Henriette Thompson, Director of Partnerships, and her staff ELCIC The Assistants to the Bishop, Mark Harris and Guenter Dahle, and the Staff of the Eastern Synod 17 Jan 2010 ACC Ms Cheryl Curtis , Executive Director of the Primate’s World Relief and Development Fund, and the staff of the Primate’s Fund ELCIC Mr. Robert Granke, Executive Director, Canadian Lutheran