Documents, Part VIII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texas Nepotism Laws Made Easy

Texas Nepotism Laws Made Easy 2016 Editor Zindia Thomas Assistant General Counsel Texas Municipal League www.tml.org Updated July 2016 Table of Contents 1. What is nepotism? .................................................................................................................... 1 2. What types of local government officials are subject to the nepotism laws? .......................... 1 3. What types of actions are generally prohibited under the nepotism law? ............................... 1 4. What relatives of a public official are covered by the statutory limitations on relationships by consanguinity (blood)? .................................................................................. 1 5. What relationships by affinity (marriage) are covered by the statutory limitations? .............. 2 6. What happens if it takes two marriages to establish the relationship with the public official? ......................................................................................................................... 3 7. What actions must a public official take if he or she has a nepotism conflict? ....................... 3 8. Do the nepotism laws apply to cities with a population of less than 200? .............................. 3 9. May a close relative be appointed to an unpaid position? ....................................................... 3 10. May other members of a governing body vote to hire a person who is a close relative of a public official if the official with the nepotism conflict abstains from deliberating and/or -

Stages of Papal Law

Journal of the British Academy, 5, 37–59. DOI https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/005.037 Posted 00 March 2017. © The British Academy 2017 Stages of papal law Raleigh Lecture on History read 1 November 2016 DAVID L. D’AVRAY Fellow of the British Academy Abstract: Papal law is known from the late 4th century (Siricius). There was demand for decretals and they were collected in private collections from the 5th century on. Charlemagne’s Admonitio generalis made papal legislation even better known and the Pseudo-Isidorian collections brought genuine decretals also to the wide audience that these partly forged collections reached. The papal reforms from the 11th century on gave rise to a new burst of papal decretals, and collections of them, culminating in the Liber Extra of 1234. The Council of Trent opened a new phase. The ‘Congregation of the Council’, set up to apply Trent’s non-dogmatic decrees, became a new source of papal law. Finally, in 1917, nearly a millennium and a half of papal law was codified by Cardinal Gasparri within two covers. Papal law was to a great extent ‘demand- driven’, which requires explanation. The theory proposed here is that Catholic Christianity was composed of a multitude of subsystems, not planned centrally and each with an evolving life of its own. Subsystems frequently interfered with the life of other subsystems, creating new entanglements. This constantly renewed complexity had the function (though not the purpose) of creating and recreating demand for papal law to sort out the entanglements between subsystems. For various reasons other religious systems have not generated the same demand: because the state plays a ‘papal’ role, or because the units are small, discrete and simple, or thanks to a clear simple blueprint, or because of conservatism combined with a tolerance of some inconsistency. -

Legislating First Cousin Marriage in the Progressive Era

KISSING COUSINS: LEGISLATING FIRST COUSIN MARRIAGE IN THE PROGRESSIVE ERA Lori Jean Wilson Consanguineous or close-kin marriages are older than history itself. They appear in the religious texts and civil records of the earliest known societies, both nomadic and sedentary. Examples of historical cousin-marriages abound. However, one should not assume that consanguineous partnerships are archaic or products of a bygone era. In fact, Dr. Alan H. Bittles, a geneticist who has studied the history of cousin-marriage legislation, reported to the New York Times in 2009 that first-cousin marriages alone account for 10 percent of global marriages.1 As of 2010, twenty-six states in the United States permit first cousin marriage. Despite this legal acceptance, the stigma attached to first-cousin marriage persists. Prior to the mid- nineteenth century, however, the American public showed little distaste toward the practice of first cousin marriage. A shift in scientific opinion emerged in the mid-nineteenth century and had anthropologists questioning whether the custom had a place in western civilization or if it represented a throwback to barbarism. The significant shift in public opinion however, occurred during the Progressive Era as the discussion centered on genetics and eugenics. The American public vigorously debated whether such unions were harmful or beneficial to the children produced by first cousin unions. The public also debated what role individual states, through legislation, should take in restricting the practice of consanguineous marriages. While divergent opinions emerged regarding the effects of first cousin marriage, the creation of healthy children and a better, stronger future generation of Americans remained the primary goal of Americans on both sides of the debate. -

MANUAL of POLICY Title Nepotism: Public Officials 1512 Legal

MANUAL OF POLICY Title Nepotism: Public Officials 1512 Legal Authority Approval of the Board of Trustees Page 1 of 2 Date Approved by Board Board Minute Order dated November 26, 2019 I. Purpose The purpose of this policy is to provide provisions regarding nepotism prohibition of public officials as defined by the consanguinity and affinity relationship. II. Policy A. Nepotism Prohibitions Applicable to Public Officials As public officials, the members of the Board of Trustees and the College President are subject to the nepotism prohibitions of Chapter 573 of the Texas Government Code. South Texas College shall not employ any person related within the second degree by affinity (marriage) or within the third degree by consanguinity (blood) to any member of the Board or the College President when the salary, fees, or compensation of the employee is paid from public funds or fees of office. A nepotism prohibition is not applicable to the employment of an individual with the College if: 1) the individual is employed in the position immediately before the election or appointment of the public official to whom the individual is related in a prohibited degree; and 2) that prior employment of the individual is continuous for at least: a. 30 days, if the public official is appointed; b. six months, if the public official is elected at an election other than the general election for state and county officers; or c. one year, if the public official is elected at the general election for state and county officers. If an individual whose employment is not subject to the nepotism prohibition continues in a position, the College President or the member of the Board of Trustees to whom the individual is related in a prohibited degree may not participate in any deliberation or voting on the employment, reemployment, change in status, compensation, or dismissal of the individual if that action applies only to the individual and is not taken regarding a bona fide class or category of employees. -

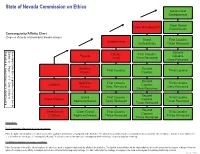

Third Degree of Consanguinity

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

The Falsification of History, Especially in Reference to the Reformation and the Characters of the Reformers, As Pertinacious

“THE FALSIFICATION OF HISTORY, ESPECIALLY IN REFERENCE TO THE REFORMATION AND THE CHARACTERS OF THE REFORMERS, AS PERTINACIOUSLY REPEATED BY THE ADVOCATES OF RITUALISM.” Church Association Tract 12 BY THE REV. T. P. BOULTBEE, M.A., LL.D., PRINCIPAL OF ST JOHN’S HALL, THEOLOGICAL COLLEGE, HIGHBURY, MIDDLESEX. “WOE unto them that call evil good, and good evil; that put darkness for light, and light for darkness; that put bitter for sweet, and sweet for bitter. Woe unto them . which justify the wicked for reward, and take away the righteousness of the righteous from him.” What darkness is like the darkness of bewildering falsehood, and what light is like the truth? Once One walked this earth who called Himself “The Truth.’’ Brightly beamed the full-orbed face of that Eternal Truth on the world’s darkness. But around Him surged the legions of that opposite who is called “the father of lies;” the traitor practised his treason; and “false witness was sought to put Him to death.” Calm and silent the august face of the Truth gleamed through the falsehood. But the gathering lies prevailed. Affixed to the accursed cross, the Truth Himself expired, and all was dark. “The sun was darkened,” and “there was darkness over all the earth.” And so He who was the Truth was laid in the tomb, and the power of falsehood prevailed in its final triumph. Nay! this was the very victory of the Truth of God! The blood did but seal the covenant. “Every promise of God was now yea and amen in Christ Jesus.” “A testament is of force after men are dead,” and now no power of Satan’s utmost lie can break the bond. -

University Microfilms 300 North Z U B Road Ann Arbor

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

The French Recension of Compilatio Tertia

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 1975 The French Recension of Compilatio Tertia Kenneth Pennington The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Kenneth Pennington, The French Recension of Compilatio Tertia, 5 BULL. MEDIEVAL CANON L. 53 (1975). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The French recension of Compilatio tertia* Petrus Beneventanus compiled a collection of Pope Innocent III's decretal letters in 1209 which covered the first twelve years of Innocent's pontificate. In 1209/10, Innocent authenticated the collection and sent it to the masters and students in Bologna. His bull (Devotioni vestrae), said Innocent, was to remove any scruples that the lawyers might have about using the collection in the schools and courts. The lawyers called the collection Compilatio tertia; it was the first officially sanctioned collection of papal decretals and has become a benchmark for the growing sophistication of European jurisprudence in the early thirteenth century.1 The modern investigation of the Compilationes antiquae began in the sixteenth century when Antonius Augustinus edited the first four compilations and publish- ed them in 1576. His edition was later republished in Paris (1609 and 1621) and as part of an Opera omnia in Lucca (1769). -

Dido: Power and Indulgence in Le Roman D'eneas

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects Honors Program 12-2009 Dido: Power and Indulgence in Le Roman d’Eneas Muriel McGregor Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation McGregor, Muriel, "Dido: Power and Indulgence in Le Roman d’Eneas" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects. 54. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors/54 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dido: Power and Indulgence in Le Roman d’Eneas By Muriel McGregor Dr. Jones HIST 4990 8 December 2009 Figure 1: Dido and Aeneas1 Section I: Classical Revival and Le Roman d’Eneas During the twelfth century, medieval Western Europe experienced a revival of interest in classical literature. Key Greek and Latin texts had been preserved in Rome’s public and private libraries during the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West. In the sixth and seventh centuries, monastic Christian scholars such as Cassiodorus (born ca. 485 AD) and Benedict of Nursia (480 – 547 AD) established scriptoria, places for copying manuscripts, in their monasteries. There they transcribed and stored classical collections.2 In the late eighth and ninth centuries, the Frankish King and Emperor of the Romans, Charlemagne (742-814 AD) renewed the preservation and dissemination of ancient literature as part of his intellectual and cultural revival, known today as the Carolingian Renaissance. -

Annulment in Church and State

DePaul Law Review Volume 5 Issue 2 Spring-Summer 1956 Article 2 Annulment in Church and State Albert A. Vail Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Albert A. Vail, Annulment in Church and State, 5 DePaul L. Rev. 216 (1956) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol5/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANNULMENT IN CHURCH1 AND STATE2 ALBERT A. VAIL SA RESULT of the position which a lawyer occupies in his com- munity and of the very nature of the practice of law, nearly every legal practitioner from time to time is consulted about marriage problems. Perhaps in no other type of problem, upon which we attorneys are consulted, do we have such a good opportunity to act as social physicians as in the case of marital problems which are presented to us. Many of the persons who present their marriage difficulties to the lawyer are Catholics. Regardless of the religious tenets of the attorney, he will recognize the fact that his Catholic client is bound by two systems of law, the civil and the ecclesiastical. Knowing this he will be conscious of the fact that if he is to reach a solution to the problem, a solution which will be truly beneficial to his client, it must needs be a solution which is in conformity with both systems of law to which his client is subject. -

Louisiana Appellate Practice Contents

Louisiana Appellate Practice Contents Supervisory writs — courts of appeal ............................................................................ 2 Civil appeals ................................................................................................................... 9 Louisiana Supreme Court writ practice ...................................................................... 16 Rule for citing Louisiana cases .................................................................................... 22 Introduction In this presentation, I hope to give you some of the information you will need to handle your first application for a supervisory writ, your first appeal, and your first application to the Louisiana Supreme Court for a writ of review. To download a copy of these materials, the accompanying PowerPoint presentation, or other appellate-practice materials, please visit Louisiana Civil Appeals at http://raymondpward.typepad.com/. Look for the entry dated May 10, 2017, or type “Bridging the Gap” in the Google search box. These materials were prepared for a one-hour presentation to lawyers as an introduction to Louisiana appellate procedure. They are not intended to be a comprehensive review of Louisiana appellate law; nor are they a substitute for an experienced appellate attorney or for your own legal research. Any authority cited in these materials may be outdated by the time you read this. Remember that laws and court rules may change. Copyright © 2017 by Raymond P. Ward 1 Supervisory writs – courts of appeal Can this interlocutory judgment be reviewed by supervisory writ? Theoretically, any interlocutory judgment can be subject of writ application. But in reality, writ application will be seriously considered only for certain classes of judgments. Irreparable injury. If a judgment causes irreparable injury, it is a good candidate for review by supervisory writ. “Irreparable injury” is a term of art, meaning that any error in the judgment cannot, as a practical matter, be corrected on appeal following final judgment. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of a History of the Reformation (Vol. 1 of 2) by Thomas M

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A History of the Reformation (Vol. 1 of 2) by Thomas M. Lindsay This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: A History of the Reformation (Vol. 1 of 2) Author: Thomas M. Lindsay Release Date: August 29, 2012 [Ebook 40615] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A HISTORY OF THE REFORMATION (VOL. 1 OF 2)*** International Theological Library A History of The Reformation By Thomas M. Lindsay, M.A., D.D. Principal, The United Free Church College, Glasgow In Two Volumes Volume I The Reformation in Germany From Its Beginning to the Religious Peace of Augsburg Edinburgh T. & T. Clark 1906 Contents Series Advertisement. 2 Dedication. 6 Preface. 7 Book I. On The Eve Of The Reformation. 11 Chapter I. The Papacy. 11 § 1. Claim to Universal Supremacy. 11 § 2. The Temporal Supremacy. 16 § 3. The Spiritual Supremacy. 18 Chapter II. The Political Situation. 29 § 1. The small extent of Christendom. 29 § 2. Consolidation. 30 § 3. England. 31 § 4. France. 33 § 5. Spain. 37 § 6. Germany and Italy. 41 § 7. Italy. 43 § 8. Germany. 46 Chapter III. The Renaissance. 53 § 1. The Transition from the Mediæval to the Modern World. 53 § 2. The Revival of Literature and Art. 56 § 3. Its earlier relation to Christianity. 59 § 4. The Brethren of the Common Lot.