Roman Law Influences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texas Nepotism Laws Made Easy

Texas Nepotism Laws Made Easy 2016 Editor Zindia Thomas Assistant General Counsel Texas Municipal League www.tml.org Updated July 2016 Table of Contents 1. What is nepotism? .................................................................................................................... 1 2. What types of local government officials are subject to the nepotism laws? .......................... 1 3. What types of actions are generally prohibited under the nepotism law? ............................... 1 4. What relatives of a public official are covered by the statutory limitations on relationships by consanguinity (blood)? .................................................................................. 1 5. What relationships by affinity (marriage) are covered by the statutory limitations? .............. 2 6. What happens if it takes two marriages to establish the relationship with the public official? ......................................................................................................................... 3 7. What actions must a public official take if he or she has a nepotism conflict? ....................... 3 8. Do the nepotism laws apply to cities with a population of less than 200? .............................. 3 9. May a close relative be appointed to an unpaid position? ....................................................... 3 10. May other members of a governing body vote to hire a person who is a close relative of a public official if the official with the nepotism conflict abstains from deliberating and/or -

Stages of Papal Law

Journal of the British Academy, 5, 37–59. DOI https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/005.037 Posted 00 March 2017. © The British Academy 2017 Stages of papal law Raleigh Lecture on History read 1 November 2016 DAVID L. D’AVRAY Fellow of the British Academy Abstract: Papal law is known from the late 4th century (Siricius). There was demand for decretals and they were collected in private collections from the 5th century on. Charlemagne’s Admonitio generalis made papal legislation even better known and the Pseudo-Isidorian collections brought genuine decretals also to the wide audience that these partly forged collections reached. The papal reforms from the 11th century on gave rise to a new burst of papal decretals, and collections of them, culminating in the Liber Extra of 1234. The Council of Trent opened a new phase. The ‘Congregation of the Council’, set up to apply Trent’s non-dogmatic decrees, became a new source of papal law. Finally, in 1917, nearly a millennium and a half of papal law was codified by Cardinal Gasparri within two covers. Papal law was to a great extent ‘demand- driven’, which requires explanation. The theory proposed here is that Catholic Christianity was composed of a multitude of subsystems, not planned centrally and each with an evolving life of its own. Subsystems frequently interfered with the life of other subsystems, creating new entanglements. This constantly renewed complexity had the function (though not the purpose) of creating and recreating demand for papal law to sort out the entanglements between subsystems. For various reasons other religious systems have not generated the same demand: because the state plays a ‘papal’ role, or because the units are small, discrete and simple, or thanks to a clear simple blueprint, or because of conservatism combined with a tolerance of some inconsistency. -

Legislating First Cousin Marriage in the Progressive Era

KISSING COUSINS: LEGISLATING FIRST COUSIN MARRIAGE IN THE PROGRESSIVE ERA Lori Jean Wilson Consanguineous or close-kin marriages are older than history itself. They appear in the religious texts and civil records of the earliest known societies, both nomadic and sedentary. Examples of historical cousin-marriages abound. However, one should not assume that consanguineous partnerships are archaic or products of a bygone era. In fact, Dr. Alan H. Bittles, a geneticist who has studied the history of cousin-marriage legislation, reported to the New York Times in 2009 that first-cousin marriages alone account for 10 percent of global marriages.1 As of 2010, twenty-six states in the United States permit first cousin marriage. Despite this legal acceptance, the stigma attached to first-cousin marriage persists. Prior to the mid- nineteenth century, however, the American public showed little distaste toward the practice of first cousin marriage. A shift in scientific opinion emerged in the mid-nineteenth century and had anthropologists questioning whether the custom had a place in western civilization or if it represented a throwback to barbarism. The significant shift in public opinion however, occurred during the Progressive Era as the discussion centered on genetics and eugenics. The American public vigorously debated whether such unions were harmful or beneficial to the children produced by first cousin unions. The public also debated what role individual states, through legislation, should take in restricting the practice of consanguineous marriages. While divergent opinions emerged regarding the effects of first cousin marriage, the creation of healthy children and a better, stronger future generation of Americans remained the primary goal of Americans on both sides of the debate. -

Historical Notes on the Canon Law on Solemnized Marriage

The Catholic Lawyer Volume 2 Number 2 Volume 2, April 1956, Number 2 Article 3 Historical Notes on the Canon Law on Solemnized Marriage William F. Cahill, B.A., J.C.D. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/tcl Part of the Catholic Studies Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Catholic Lawyer by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The nature and importance of the Catholic marriage ceremony is best understood in the light of historicalantecedents. With such a perspective, the canon law is not likely to seem arbitrary. HISTORICAL NOTES ON THE CANON LAW ON SOLEMNIZED MARRIAGE WILLIAM F. CAHILL, B.A., J.C.D.* T HE law of the Catholic Church requires, under pain of nullity, that the marriages of Catholics shall be celebrated in the presence of the parties, of an authorized priest and of two witnesses.1 That law is the product of an historical development. The present legislation con- sidered apart from its historical antecedents can be made to seem arbitrary. Indeed, if the historical background is misconceived, the 2 present law may be seen as tyrannical. This essay briefly states the correlation between the present canons and their antecedents in history. For clarity, historical notes are not put in one place, but follow each of the four headings under which the present Church discipline is described. -

![Medical Miscellany [Manuscript]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1888/medical-miscellany-manuscript-341888.webp)

Medical Miscellany [Manuscript]

These crowdsourced transcriptions were made by EMROC classes and transcribathons (emroc.hypotheses.org), Shakespeare’s World volunteers, Folger docents, and paleography students. Original line endings, spelling, and punctuation are maintained and abbreviations are expanded, but the overall layout is not reproduced. Please contact [email protected] with transcription errors. Digitized images are available on LUNA and XML versions are available upon request. All transcriptions can be freely used and shared without restrictions, but please acknowledge “Folger Shakespeare Library” and the source manuscript’s call number. Last Updated: 8 April 2021 E.a.5: Medical miscellany [manuscript]. front outside cover front inside cover || front endleaf 1 recto Salomon dicitur Pacificus Iohannes dicitur Amor Dej./ Cicero:/ Cum biduum cibo se abstinuisset, Fæbris discessit./ J Harvey 181 front endleaf 1 verso || insertion 1 recto Ickwell = Bury Biggleswade Old M.S.S. 8 1 Gradations of the Callender glass. (weather glass) M.S. 2 Treatise on Medecine 1634 by Dan Worrall & Tho Burton M.S. 3. Receipts for cooking also Medecine MS M.S. insertion 1 verso || insertion 2 recto insertion 2 verso || folio 1 recto Gradations upon the Callendar Glasse 1. The propertie of the Water is to Asscend with Cold,and descend with heate upon the Least & euery change of the Weather Certainely./ 2. By the suddaine falling of the Water is a certaine signe of Rayne; for Example, If the Water fall a degree or two in 7 or 8 howers, it will surely rayne presently, or within 10 or 12 howers after./ 3. If the Water fall in the night season it will surely Rayne, for Example, If the water be fallen any Lower in the morning att Sunn riseing, then it was overnight att Sunn setting it will surely raine the day following before midnight./ 4. -

Humanum Genus Encyclical of Pope Leo Xiii on Freemasonry

The Holy See HUMANUM GENUS ENCYCLICAL OF POPE LEO XIII ON FREEMASONRY To the Patriarchs, Primates, Archbishops, and Bishops of the Catholic World in Grace and Communion with the Apostolic See. The race of man, after its miserable fall from God, the Creator and the Giver of heavenly gifts, "through the envy of the devil," separated into two diverse and opposite parts, of which the one steadfastly contends for truth and virtue, the other of those things which are contrary to virtue and to truth. The one is the kingdom of God on earth, namely, the true Church of Jesus Christ; and those who desire from their heart to be united with it, so as to gain salvation, must of necessity serve God and His only-begotten Son with their whole mind and with an entire will. The other is the kingdom of Satan, in whose possession and control are all whosoever follow the fatal example of their leader and of our first parents, those who refuse to obey the divine and eternal law, and who have many aims of their own in contempt of God, and many aims also against God. 2. This twofold kingdom St. Augustine keenly discerned and described after the manner of two cities, contrary in their laws because striving for contrary objects; and with a subtle brevity he expressed the efficient cause of each in these words: "Two loves formed two cities: the love of self, reaching even to contempt of God, an earthly city; and the love of God, reaching to contempt of self, a heavenly one."(1) At every period of time each has been in conflict with the other, with a variety and multiplicity of weapons and of warfare, although not always with equal ardour and assault. -

MANUAL of POLICY Title Nepotism: Public Officials 1512 Legal

MANUAL OF POLICY Title Nepotism: Public Officials 1512 Legal Authority Approval of the Board of Trustees Page 1 of 2 Date Approved by Board Board Minute Order dated November 26, 2019 I. Purpose The purpose of this policy is to provide provisions regarding nepotism prohibition of public officials as defined by the consanguinity and affinity relationship. II. Policy A. Nepotism Prohibitions Applicable to Public Officials As public officials, the members of the Board of Trustees and the College President are subject to the nepotism prohibitions of Chapter 573 of the Texas Government Code. South Texas College shall not employ any person related within the second degree by affinity (marriage) or within the third degree by consanguinity (blood) to any member of the Board or the College President when the salary, fees, or compensation of the employee is paid from public funds or fees of office. A nepotism prohibition is not applicable to the employment of an individual with the College if: 1) the individual is employed in the position immediately before the election or appointment of the public official to whom the individual is related in a prohibited degree; and 2) that prior employment of the individual is continuous for at least: a. 30 days, if the public official is appointed; b. six months, if the public official is elected at an election other than the general election for state and county officers; or c. one year, if the public official is elected at the general election for state and county officers. If an individual whose employment is not subject to the nepotism prohibition continues in a position, the College President or the member of the Board of Trustees to whom the individual is related in a prohibited degree may not participate in any deliberation or voting on the employment, reemployment, change in status, compensation, or dismissal of the individual if that action applies only to the individual and is not taken regarding a bona fide class or category of employees. -

Third Degree of Consanguinity

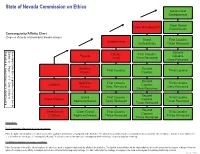

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

Documents, Part VIII

Sec. viIi CONTENTS vIiI–1 PART VIII. GLOSSATORS: MARRIAGE CONTENTS A. GRATIAN OF BOLOGNA, CONCORDANCE OF DISCORDANT CANONS, C.27 q.2 .............VIII–2 B. PETER LOMBARD, FOUR BOOKS OF SENTENCES, 4.26–7 ...................................................VIII–12 C. DECRETALS OF ALEXANDER III (1159–1181) AND INNOCENT III (1198–1216) 1B. Veniens ... (before 1170), ItPont 3:404 .....................................................................................VIII–16 2. Sicut romana (1173 or 1174), 1 Comp. 4.4.5(7) ..........................................................................VIII–16 3. Ex litteris (1175 X 1181), X 4.16.2..............................................................................................VIII–16 4. Licet praeter solitum (1169 X 1179, probably 1176 or1177), X 4.4.3.........................................VIII–17 5. Significasti (1159 X 1181), 1 Comp. 4.4.6(8)..............................................................................VIII–18 6 . Sollicitudini (1166 X 1181), 1 Comp. 4.5.4(6) ............................................................................VIII–19 7 . Veniens ad nos (1176 X 1181), X 4.1.15 .....................................................................................VIII–19 8m. Tuas dutu (1200) .......................................................................................................................VIII–19 9 . Quod nobis (1170 or 1171), X 4.3.1 ............................................................................................VIII–19 10 . Tuae nobis -

University Microfilms 300 North Z U B Road Ann Arbor

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

'How the Corpse of a Most Mighty King…' the Use of the Death and Burial of the English Monarch

1 Doctoral Dissertation ‘How the Corpse of a Most Mighty King…’ The Use of the Death and Burial of the English Monarch (From Edward to Henry I) by James Plumtree Supervisors: Gábor Klaniczay, Gerhard Jaritz Submitted to the Medieval Studies Department and the Doctoral School of History Central European University, Budapest in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy CEU eTD Collection Budapest 2014 2 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................... 2 TABLE OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................ 3 ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 6 1. ‘JOYFULLY TAKEN UP TO LIVE WITH GOD’ THE ALTERED PASSING OF EDWARD .......................................................................... 13 1. 1. The King’s Two Deaths in MS C and the Vita Ædwardi Regis .......................... 14 1. 2. Dead Ends: Sulcard’s Prologus and the Bayeux Tapestry .................................. 24 1. 3. The Smell of Sanctity, A Whiff of Fraud: Osbert and the 1102 Translation ....... 31 1. 4. The Death in Histories: Orderic, Malmesbury, and Huntingdon ......................... 36 1. 5. ‘We Have Him’: The King’s Cadaver at Westminster ....................................... -

Dido: Power and Indulgence in Le Roman D'eneas

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects Honors Program 12-2009 Dido: Power and Indulgence in Le Roman d’Eneas Muriel McGregor Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation McGregor, Muriel, "Dido: Power and Indulgence in Le Roman d’Eneas" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects. 54. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors/54 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dido: Power and Indulgence in Le Roman d’Eneas By Muriel McGregor Dr. Jones HIST 4990 8 December 2009 Figure 1: Dido and Aeneas1 Section I: Classical Revival and Le Roman d’Eneas During the twelfth century, medieval Western Europe experienced a revival of interest in classical literature. Key Greek and Latin texts had been preserved in Rome’s public and private libraries during the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West. In the sixth and seventh centuries, monastic Christian scholars such as Cassiodorus (born ca. 485 AD) and Benedict of Nursia (480 – 547 AD) established scriptoria, places for copying manuscripts, in their monasteries. There they transcribed and stored classical collections.2 In the late eighth and ninth centuries, the Frankish King and Emperor of the Romans, Charlemagne (742-814 AD) renewed the preservation and dissemination of ancient literature as part of his intellectual and cultural revival, known today as the Carolingian Renaissance.