Legislating First Cousin Marriage in the Progressive Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins and Consequences of Kin Networks and Marriage Practices

The origins and consequences of kin networks and marriage practices by Duman Bahramirad M.Sc., University of Tehran, 2007 B.Sc., University of Tehran, 2005 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Economics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences c Duman Bahramirad 2018 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2018 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Duman Bahramirad Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Economics) Title: The origins and consequences of kin networks and marriage practices Examining Committee: Chair: Nicolas Schmitt Professor Gregory K. Dow Senior Supervisor Professor Alexander K. Karaivanov Supervisor Professor Erik O. Kimbrough Supervisor Associate Professor Argyros School of Business and Economics Chapman University Simon D. Woodcock Supervisor Associate Professor Chris Bidner Internal Examiner Associate Professor Siwan Anderson External Examiner Professor Vancouver School of Economics University of British Columbia Date Defended: July 31, 2018 ii Ethics Statement iii iii Abstract In the first chapter, I investigate a potential channel to explain the heterogeneity of kin networks across societies. I argue and test the hypothesis that female inheritance has historically had a posi- tive effect on in-marriage and a negative effect on female premarital relations and economic partic- ipation. In the second chapter, my co-authors and I provide evidence on the positive association of in-marriage and corruption. We also test the effect of family ties on nepotism in a bribery experi- ment. The third chapter presents my second joint paper on the consequences of kin networks. -

Change in the Prevalence and Determinants of Consanguineous Marriages in India Between National Family and Health Surveys (NFHS) 1 (1992–1993) and 4 (2015–2016)

Wayne State University Human Biology Open Access Pre-Prints WSU Press 11-10-2020 Change in the Prevalence and Determinants of Consanguineous Marriages in India between National Family and Health Surveys (NFHS) 1 (1992–1993) and 4 (2015–2016) Mir Azad Kalam Narasinha Dutt College, Howrah, India Santosh Kumar Sharma International Institute of Population Sciences Saswata Ghosh Institute of Development Studies Kolkata (IDSK) Subho Roy University of Calcutta Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol_preprints Recommended Citation Kalam, Mir Azad; Sharma, Santosh Kumar; Ghosh, Saswata; and Roy, Subho, "Change in the Prevalence and Determinants of Consanguineous Marriages in India between National Family and Health Surveys (NFHS) 1 (1992–1993) and 4 (2015–2016)" (2020). Human Biology Open Access Pre-Prints. 178. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol_preprints/178 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the WSU Press at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Human Biology Open Access Pre-Prints by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. Change in the Prevalence and Determinants of Consanguineous Marriages in India between National Family and Health Surveys (NFHS) 1 (1992–1993) and 4 (2015–2016) Mir Azad Kalam,1* Santosh Kumar Sharma,2 Saswata Ghosh,3 and Subho Roy4 1Narasinha Dutt College, Howrah, India. 2International Institute of Population Sciences, Mumbai, India. 3Institute of Development Studies Kolkata (IDSK), Kolkata, India. 4Department of Anthropology, University of Calcutta, Kolkata, India. *Correspondence to: Mir Azad Kalam, Narasinha Dutt College, 129 Belilious Road, West Bengal, Howrah 711101, India. E-mail: [email protected]. Short Title: Change in Prevalence and Determinants of Consanguineous Marriages in India KEY WORDS: NATIONAL FAMILY AND HEALTH SURVEY, CONSANGUINEOUS MARRIAGE, DETERMINANTS, RELIGION, INDIA. -

Texas Nepotism Laws Made Easy

Texas Nepotism Laws Made Easy 2016 Editor Zindia Thomas Assistant General Counsel Texas Municipal League www.tml.org Updated July 2016 Table of Contents 1. What is nepotism? .................................................................................................................... 1 2. What types of local government officials are subject to the nepotism laws? .......................... 1 3. What types of actions are generally prohibited under the nepotism law? ............................... 1 4. What relatives of a public official are covered by the statutory limitations on relationships by consanguinity (blood)? .................................................................................. 1 5. What relationships by affinity (marriage) are covered by the statutory limitations? .............. 2 6. What happens if it takes two marriages to establish the relationship with the public official? ......................................................................................................................... 3 7. What actions must a public official take if he or she has a nepotism conflict? ....................... 3 8. Do the nepotism laws apply to cities with a population of less than 200? .............................. 3 9. May a close relative be appointed to an unpaid position? ....................................................... 3 10. May other members of a governing body vote to hire a person who is a close relative of a public official if the official with the nepotism conflict abstains from deliberating and/or -

Stages of Papal Law

Journal of the British Academy, 5, 37–59. DOI https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/005.037 Posted 00 March 2017. © The British Academy 2017 Stages of papal law Raleigh Lecture on History read 1 November 2016 DAVID L. D’AVRAY Fellow of the British Academy Abstract: Papal law is known from the late 4th century (Siricius). There was demand for decretals and they were collected in private collections from the 5th century on. Charlemagne’s Admonitio generalis made papal legislation even better known and the Pseudo-Isidorian collections brought genuine decretals also to the wide audience that these partly forged collections reached. The papal reforms from the 11th century on gave rise to a new burst of papal decretals, and collections of them, culminating in the Liber Extra of 1234. The Council of Trent opened a new phase. The ‘Congregation of the Council’, set up to apply Trent’s non-dogmatic decrees, became a new source of papal law. Finally, in 1917, nearly a millennium and a half of papal law was codified by Cardinal Gasparri within two covers. Papal law was to a great extent ‘demand- driven’, which requires explanation. The theory proposed here is that Catholic Christianity was composed of a multitude of subsystems, not planned centrally and each with an evolving life of its own. Subsystems frequently interfered with the life of other subsystems, creating new entanglements. This constantly renewed complexity had the function (though not the purpose) of creating and recreating demand for papal law to sort out the entanglements between subsystems. For various reasons other religious systems have not generated the same demand: because the state plays a ‘papal’ role, or because the units are small, discrete and simple, or thanks to a clear simple blueprint, or because of conservatism combined with a tolerance of some inconsistency. -

Cousin Marriage & Inbreeding Depression

Evidence of Inbreeding Depression: Saudi Arabia Saudi Intermarriages Have Genetic Costs [Important note from Raymond Hames (your instructor). Cousin marriage in the United States is not as risky compared to cousin marriage in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere where there is a long history of repeated inter-marriage between close kin. Ordinary cousins without a history previous intermarriage are related to one another by 0.0125. However, in societies with a long history of intermarriage, relatedness is much higher. For US marriages a study published in The Journal of Genetic Counseling in 2002 said that the risk of serious genetic defects like spina bifida and cystic fibrosis in the children of first cousins indeed exists but that it is rather small, 1.7 to 2.8 percentage points higher than for children of unrelated parents, who face a 3 to 4 percent risk — or about the equivalent of that in children of women giving birth in their early 40s. The study also said the risk of mortality for children of first cousins was 4.4 percentage points higher.] By Howard Schneider Washington Post Foreign Service Sunday, January 16, 2000; Page A01 RIYADH, Saudi Arabia-In the centuries that this country's tribes have scratched a life from the Arabian Peninsula, the rule of thumb for choosing a marriage partner has been simple: Keep it in the family, a cousin if possible, or at least a tribal kin who could help conserve resources and contribute to the clan's support and defense. But just as that method of matchmaking served a purpose over the generations, providing insurance against a social or financial mismatch, so has it exacted a cost--the spread of genetic disease. -

Marriage Outlaws: Regulating Polygamy in America

Faucon_jci (Do Not Delete) 1/6/2015 3:10 PM Marriage Outlaws: Regulating Polygamy in America CASEY E. FAUCON* Polygamist families in America live as outlaws on the margins of society. While the insular groups living in and around Utah are recognized by mainstream society, Muslim polygamists (including African‐American polygamists) living primarily along the East Coast are much less familiar. Despite the positive social justifications that support polygamous marriage recognition, the practice remains taboo in the eyes of the law. Second and third polygamous wives are left without any legal recognition or protection. Some legal scholars argue that states should recognize and regulate polygamous marriage, specifically by borrowing from business entity models to draft default rules that strive for equal bargaining power and contract‐based, negotiated rights. Any regulatory proposal, however, must both fashion rules that are applicable to an American legal system, and attract religious polygamists to regulation by focusing on the religious impetus and social concerns behind polygamous marriage practices. This Article sets out a substantive and procedural process to regulate religious polygamous marriages. This proposal addresses concerns about equality and also reflects the religious and as‐practiced realities of polygamy in the United States. INTRODUCTION Up to 150,000 polygamists live in the United States as outlaws on the margins of society.1 Although every state prohibits and criminalizes polygamy,2 Copyright © 2014 by Casey E. Faucon. * Casey E. Faucon is the 2013‐2015 William H. Hastie Fellow at the University of Wisconsin Law School. J.D./D.C.L., LSU Paul M. Hebert School of Law. -

Politics and Marriage in South Kamen (Chad)

POLITICS AND MARRIAGE IN SOUTH KANEM (CHAD) : A STATISTICAL PRESENTATION OF ENDOGAMY FROM 1895 TO 1975 Edouard CONTE SYST~ES MATRIMONIAUX AU SUD KANEM (TCHAD): PRÉSENTATION STATISTIQUE DE L'ENDOGAMIE DE 18% b 1975 Le but du prkwzt article est de faire connaître les résrdiuts préliminuiws d’une étude de l’endogamie et de l’organisation lignagère menée sur une base comparative aupr& des deux principales strates sociales renconirées chez les populations kanambti des rives nord-est du Lac Tchad. Le mot kanambti peut dèsigtzer toute personne originaire du Kattem ef dottf la langne maternelle est le lranambukanambti. Toutefois, dans l’usage courant, cetie dèt~ntnittatiot~ est rèserv& nus ligttages donf les prétentions généalogiques remontent aux Sefarva ou à leurs successeurs ou alliés entre qui le mariage est irnditior~nellernet~~ licite. Partni les hommes libres, on distiilgue, cependant, les (<gens de la lance j> ou h’anemborr se considtirant Q nobles jj au sens le plus large et les + gens de l’arc b, mieux connus SOLLS l’appellation de HerltlSc1 que nous rapporttkent dèjà les erplorateurs allemands BARTH et NACHTIGAL. Ce tertne signifie forgeron en arabe mais les Kanembou opèrent une distinction entre les artisans forgerons (kzig&nà) et les membres d’un lignaye dit ’ forgeron ’ ((II?). Les Haddad reprèsentenf environ 20 :/o de la population kanem bou muis cefte proporliotl subif de larges variations d’un endrolb ti l’autre. Le choix de leurs lieue de résidence est largement fonctiotl des exigences économiques de leurs maîtres ainsi que du degré d’autonomie politique qu’ils oni su conquérir. -

MANUAL of POLICY Title Nepotism: Public Officials 1512 Legal

MANUAL OF POLICY Title Nepotism: Public Officials 1512 Legal Authority Approval of the Board of Trustees Page 1 of 2 Date Approved by Board Board Minute Order dated November 26, 2019 I. Purpose The purpose of this policy is to provide provisions regarding nepotism prohibition of public officials as defined by the consanguinity and affinity relationship. II. Policy A. Nepotism Prohibitions Applicable to Public Officials As public officials, the members of the Board of Trustees and the College President are subject to the nepotism prohibitions of Chapter 573 of the Texas Government Code. South Texas College shall not employ any person related within the second degree by affinity (marriage) or within the third degree by consanguinity (blood) to any member of the Board or the College President when the salary, fees, or compensation of the employee is paid from public funds or fees of office. A nepotism prohibition is not applicable to the employment of an individual with the College if: 1) the individual is employed in the position immediately before the election or appointment of the public official to whom the individual is related in a prohibited degree; and 2) that prior employment of the individual is continuous for at least: a. 30 days, if the public official is appointed; b. six months, if the public official is elected at an election other than the general election for state and county officers; or c. one year, if the public official is elected at the general election for state and county officers. If an individual whose employment is not subject to the nepotism prohibition continues in a position, the College President or the member of the Board of Trustees to whom the individual is related in a prohibited degree may not participate in any deliberation or voting on the employment, reemployment, change in status, compensation, or dismissal of the individual if that action applies only to the individual and is not taken regarding a bona fide class or category of employees. -

Third Degree of Consanguinity

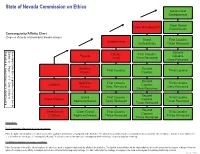

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

The Modern Opinions Regarding Polygamy of Married Men and Women in Dakar

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2013 The oM dern Opinions Regarding Polygamy of Married Men and Women in Dakar Hannah Fried-Tanzer SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons Recommended Citation Fried-Tanzer, Hannah, "The odeM rn Opinions Regarding Polygamy of Married Men and Women in Dakar" (2013). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1680. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1680 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Modern Opinions Regarding Polygamy of Married Men and Women in Dakar Fried-Tanzer, Hannah Academic Director: Diallo, Souleye Project Adviser: Gaye, Rokhaya George Washington University French and Anthropology Senegal, Dakar Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Senegal: National Identity and the Arts Program SIT Study Abroad, Fall 2013 2 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Introduction and Historical Context 3 Methodology 9 Findings/Interviews 11 Monogamy 11 Polygamy 13 Results and Analysis 21 Misgivings 24 Challenges 25 Conclusion 25 Works Cited 27 Interviews Cited 29 Appendix A: Questionnaire 30 Appendix B: Time Log 31 3 Abstract Polygamy is the practice in which a man takes multiple wives. While it is no longer legal in certain countries, it is still allowed both legally and religiously in Senegal, and is still practiced today. -

Documents, Part VIII

Sec. viIi CONTENTS vIiI–1 PART VIII. GLOSSATORS: MARRIAGE CONTENTS A. GRATIAN OF BOLOGNA, CONCORDANCE OF DISCORDANT CANONS, C.27 q.2 .............VIII–2 B. PETER LOMBARD, FOUR BOOKS OF SENTENCES, 4.26–7 ...................................................VIII–12 C. DECRETALS OF ALEXANDER III (1159–1181) AND INNOCENT III (1198–1216) 1B. Veniens ... (before 1170), ItPont 3:404 .....................................................................................VIII–16 2. Sicut romana (1173 or 1174), 1 Comp. 4.4.5(7) ..........................................................................VIII–16 3. Ex litteris (1175 X 1181), X 4.16.2..............................................................................................VIII–16 4. Licet praeter solitum (1169 X 1179, probably 1176 or1177), X 4.4.3.........................................VIII–17 5. Significasti (1159 X 1181), 1 Comp. 4.4.6(8)..............................................................................VIII–18 6 . Sollicitudini (1166 X 1181), 1 Comp. 4.5.4(6) ............................................................................VIII–19 7 . Veniens ad nos (1176 X 1181), X 4.1.15 .....................................................................................VIII–19 8m. Tuas dutu (1200) .......................................................................................................................VIII–19 9 . Quod nobis (1170 or 1171), X 4.3.1 ............................................................................................VIII–19 10 . Tuae nobis -

Examining Genetic Load: an Islamic Perspective

Review Genetics and Theology EXAMINING GENETIC LOAD: AN ISLAMIC PERSPECTIVE ARTHUR SANIOTIS* MACIEJ HENNEBERG** SUMMARY: The topic of genetic load has been theorised by various authors. Genetic load refers to the reduction of population fitness due to accumulation of deleterious genes. Genetic load points to a decline in pop- ulation fitness when compared to a ‘standard’ population. Having provided an explanation of genetic load, this article will locate genetic load in relation to historic and demographic changes. Moreover, it will discuss genetic understandings from the Qur’an and hadith. It will be argued that Islam possesses sound genetic concepts for informing Muslims about life on earth as well as choosing future spouses. Consanguineous marriage which is still prevalent in some Muslim countries, will also be examined, and will elicit recent scientific research in order to understand some of social and cultural factors for this cultural practice. Key words: Genetics, Islam, theology, Qur’an. INTRODUCTION What is Genetic Load? standard population is defined as carrying an optimum The topic of genetic load has been theorised by genotype, where no mutations arise (7). In this way, the various authors (1-7). Genetic load refers to the reduc- fittest individuals are those which have the highest tion of population fitness due to deleterious mutations. number of progeny. Therefore, harmful mutations to an The noted biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky states that individual’s genotype may reduce his/her fitness over the accumulation of deleterious mutant genes consti- generational time if such mutations are non-optimal. tutes a genetic load (3). Genetic load is a pejorative Similarly, Lynch and Gabriel argue that deleterious term describing a situation in which there is a load of mutations reduce reproductive rates of individuals (6).