Dido: Power and Indulgence in Le Roman D'eneas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texas Nepotism Laws Made Easy

Texas Nepotism Laws Made Easy 2016 Editor Zindia Thomas Assistant General Counsel Texas Municipal League www.tml.org Updated July 2016 Table of Contents 1. What is nepotism? .................................................................................................................... 1 2. What types of local government officials are subject to the nepotism laws? .......................... 1 3. What types of actions are generally prohibited under the nepotism law? ............................... 1 4. What relatives of a public official are covered by the statutory limitations on relationships by consanguinity (blood)? .................................................................................. 1 5. What relationships by affinity (marriage) are covered by the statutory limitations? .............. 2 6. What happens if it takes two marriages to establish the relationship with the public official? ......................................................................................................................... 3 7. What actions must a public official take if he or she has a nepotism conflict? ....................... 3 8. Do the nepotism laws apply to cities with a population of less than 200? .............................. 3 9. May a close relative be appointed to an unpaid position? ....................................................... 3 10. May other members of a governing body vote to hire a person who is a close relative of a public official if the official with the nepotism conflict abstains from deliberating and/or -

Stages of Papal Law

Journal of the British Academy, 5, 37–59. DOI https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/005.037 Posted 00 March 2017. © The British Academy 2017 Stages of papal law Raleigh Lecture on History read 1 November 2016 DAVID L. D’AVRAY Fellow of the British Academy Abstract: Papal law is known from the late 4th century (Siricius). There was demand for decretals and they were collected in private collections from the 5th century on. Charlemagne’s Admonitio generalis made papal legislation even better known and the Pseudo-Isidorian collections brought genuine decretals also to the wide audience that these partly forged collections reached. The papal reforms from the 11th century on gave rise to a new burst of papal decretals, and collections of them, culminating in the Liber Extra of 1234. The Council of Trent opened a new phase. The ‘Congregation of the Council’, set up to apply Trent’s non-dogmatic decrees, became a new source of papal law. Finally, in 1917, nearly a millennium and a half of papal law was codified by Cardinal Gasparri within two covers. Papal law was to a great extent ‘demand- driven’, which requires explanation. The theory proposed here is that Catholic Christianity was composed of a multitude of subsystems, not planned centrally and each with an evolving life of its own. Subsystems frequently interfered with the life of other subsystems, creating new entanglements. This constantly renewed complexity had the function (though not the purpose) of creating and recreating demand for papal law to sort out the entanglements between subsystems. For various reasons other religious systems have not generated the same demand: because the state plays a ‘papal’ role, or because the units are small, discrete and simple, or thanks to a clear simple blueprint, or because of conservatism combined with a tolerance of some inconsistency. -

Francesco Cavalli

OPÉRA DE MONTPELLIER Francesco Cavalli Opéra de Montpellier Ville de 11, boulevard Victor Hugo - CS 89024 - 34967 Montpellier Cedex 2 Montpellier Tél. 04 67 60 19 99 Fax 04 67 60 19 90 Adresse Internet : http://www.opera-montpellier.com — Email : [email protected] La Didone OPÉRA EN UN PROLOGUE ET TROIS ACTES DE FRANCESCO CAVALLI LIVRET DE FRANCESCO BUSENELLO CRÉATION A VENISE EN 1641 AU THEATRE SAN CASSIANO. PRODUCTION DE L'OPÉRA DE LAUSANNE 18, 20 et 21 janvier 2002 à l'Opéra Comédie Les Talens Lyriques Choeurs de l'Opéra de La Didone Direction, clavecin et orgue Montpellier Christophe Rousset Direction musicale Didone, Creusa, Ombra di Creusa Franck Bard Christophe Rousset Juanita Lascarro ORCHESTRE Marie-Anne Benavoli Fialho Direction des choeurs Violons Elina Bordry Enea Enrico Gatti, Nathalie Cazenave Noêlle Geny Topi Lehtipuu Gilone Gaubert-Jacques Eric Chabrol Altos Christian Chauvot Réalisation larba Judith Depoutot, Ernesto Fuentes Mezco Éric Vigner Ivan Ludlow Jun Okada Josiane Houpiez-Bainvel Étienne Leclercq Costumes Flûtes à bec Paul Quenson Anna, Cassandra Jacques Maresch Héloïse Gaillard, Katalin Varkonyi Hervé Martin Lumières Meillane Wilmotte Christophe Delarue Jean-Claude Pacuil Venere, una damigella Cornets Béatrice Parmentier Anne-Lise Sollied Frithjof Smith, Sherri Sassoon-Deschler David Gebhard, Dramaturgie et surtitres Olga Tichina Rita de Letteriis Doron Sherwin Ascanio, Amore Trombones Assistant à la direction musicale Valérie Gabail Jean-Marc Aymes Franck Poitrineau, Junon, una damigella Stefan Legée, -

Legislating First Cousin Marriage in the Progressive Era

KISSING COUSINS: LEGISLATING FIRST COUSIN MARRIAGE IN THE PROGRESSIVE ERA Lori Jean Wilson Consanguineous or close-kin marriages are older than history itself. They appear in the religious texts and civil records of the earliest known societies, both nomadic and sedentary. Examples of historical cousin-marriages abound. However, one should not assume that consanguineous partnerships are archaic or products of a bygone era. In fact, Dr. Alan H. Bittles, a geneticist who has studied the history of cousin-marriage legislation, reported to the New York Times in 2009 that first-cousin marriages alone account for 10 percent of global marriages.1 As of 2010, twenty-six states in the United States permit first cousin marriage. Despite this legal acceptance, the stigma attached to first-cousin marriage persists. Prior to the mid- nineteenth century, however, the American public showed little distaste toward the practice of first cousin marriage. A shift in scientific opinion emerged in the mid-nineteenth century and had anthropologists questioning whether the custom had a place in western civilization or if it represented a throwback to barbarism. The significant shift in public opinion however, occurred during the Progressive Era as the discussion centered on genetics and eugenics. The American public vigorously debated whether such unions were harmful or beneficial to the children produced by first cousin unions. The public also debated what role individual states, through legislation, should take in restricting the practice of consanguineous marriages. While divergent opinions emerged regarding the effects of first cousin marriage, the creation of healthy children and a better, stronger future generation of Americans remained the primary goal of Americans on both sides of the debate. -

Dido Y Eneas Ópera En Tres Actos

Conciertos pa ra Escolares FUNDACIÓN C AJA MADRID Coordin1a0d/o1r3a apñeodas gógica Ana Hernández Sanchiz Dido y Eneas Ópera en tres actos de Henry Purcell Guía Didáctica Ana Hernández Sanchiz DIDO Y ENEAS Conciertos para Escolares de la Fundación Caja Madrid 10 a 13 años Índice EL ESPECTÁCULO..........................................................................................3 LA ÓPERA BARROCA INGLESA....................................................................4 DIDO Y ENEAS o La ópera........................................................................................6 o Los autores: Henry Purcell y Nahum Tate..................................7 o El argumento................................................................................8 o Los intérpretes...............................................................................9 o Dido y Eneas en el arte.............................................................12 EL TEATRO DE SOMBRAS.............................................................................14 ACTIVIDADES 1. A modo de obertura.................................................................15 2. Versionando la versión.............................................................17 3. En viñetas...................................................................................18 4. Para cantar y tocar... el corazón de Dido.............................19 5. El lamento de la reina...............................................................20 6. Asómbrate..................................................................................21 -

A Study of the Late Antique Latin Wedding Centos

INSTITUTIONEN FÖR SPRÅK OCH LITTERATURER DE INCONEXIS CONTINUUM A Study of the Late Antique Latin Wedding Centos DE INCONEXIS CONTINUUM A Study of the Late Antique Latin Wedding Centos SARA EHRLING QuickTime och en -dekomprimerare krävs för att kunna se bilden. SARA EHRLING DE INCONEXIS CONTINUUM INSTITUTIONEN FÖR SPRÅK OCH LITTERATURER DE INCONEXIS CONTINUUM A Study of the Late Antique Latin Wedding Centos SARA EHRLING Avhandling för filosofie doktorsexamen i latin, Göteborgs universitet 2011-05-28 Disputationsupplaga Sara Ehrling 2011 ISBN: 978–91–628–8311–9 http://hdl.handle.net/2077/24990 Distribution: Institutionen för språk och litteraturer, Göteborgs universitet, Box 200, 405 30 Göteborg Acknowledgements Due to diverse turns of life, this work has followed me for several years, and I am now happy for having been able to finish it. This would not have been possible without the last years’ patient support and direction of my supervisor Professor Gunhild Vidén at the Department of Languages and Literatures. Despite her full agendas, Gunhild has always found time to read and comment on my work; in her criticism, she has in a remarkable way combined a sharp intellect with deep knowledge and sound common sense. She has also always been a good listener. For this, and for numerous other things, I admire and am deeply grateful to Gunhild. My secondary supervisor, Professor Mats Malm at the Department of Literature, History of Ideas, and Religion, has guided me with insight through the vast field of literary criticism; my discussions with him have helped me correct many mistakes and improve important lines of reasoning. -

The LEGACY of CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS in the AMERICAS New Nations and a Transatlantic Discourse of Empire

The LEGACY of CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS in the AMERICAS New Nations and a Transatlantic Discourse of Empire Elise Bartosik-Vélez The Legacy of Christopher Columbus in the Americas The LEGACY of CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS in the AMERICAS New Nations and a Transatlantic Discourse of Empire Elise Bartosik-Vélez Vanderbilt University Press NASHVILLE © 2014 by Vanderbilt University Press Nashville, Tennessee 37235 All rights reserved First printing 2014 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file LC control number 2013007832 LC classification number e112 .b294 2014 Dewey class number 970.01/5 isbn 978-0-8265-1953-5 (cloth) isbn 978-0-8265-1955-9 (ebook) For Bryan, Sam, and Sally Contents Acknowledgments ................................. ix Introduction .......................................1 chapter 1 Columbus’s Appropriation of Imperial Discourse ............................ 15 chapter 2 The Incorporation of Columbus into the Story of Western Empire ................. 44 chapter 3 Columbus and the Republican Empire of the United States ............................. 66 chapter 4 Colombia: Discourses of Empire in Spanish America ............................ 106 Conclusion: The Meaning of Empire in Nationalist Discourses of the United States and Spanish America ........................... 145 Notes ........................................... 153 Works Cited ..................................... 179 Index ........................................... 195 Acknowledgments any people helped me as I wrote this book. Michael Palencia-Roth has been an unfailing mentor and model of Methical, rigorous scholarship and human compassion. I am grate- ful for his generous help at many stages of writing this manu- script. I am also indebted to my friend Christopher Francese, of the Department of Classical Studies at Dickinson College, who has never hesitated to answer my queries about pretty much any- thing related to the classical world. -

Howard Mayer Brown Microfilm Collection Guide

HOWARD MAYER BROWN MICROFILM COLLECTION GUIDE Page individual reels from general collections using the call number: Howard Mayer Brown microfilm # ___ Scope and Content Howard Mayer Brown (1930 1993), leading medieval and renaissance musicologist, most recently ofthe University ofChicago, directed considerable resources to the microfilming ofearly music sources. This collection ofmanuscripts and printed works in 1700 microfilms covers the thirteenth through nineteenth centuries, with the bulk treating the Medieval, Renaissance, and early Baroque period (before 1700). It includes medieval chants, renaissance lute tablature, Venetian madrigals, medieval French chansons, French Renaissance songs, sixteenth to seventeenth century Italian madrigals, eighteenth century opera libretti, copies ofopera manuscripts, fifteenth century missals, books ofhours, graduals, and selected theatrical works. I Organization The collection is organized according to the microfilm listing Brown compiled, and is not formally cataloged. Entries vary in detail; some include RISM numbers which can be used to find a complete description ofthe work, other works are identified only by the library and shelf mark, and still others will require going to the microfilm reel for proper identification. There are a few microfilm reel numbers which are not included in this listing. Brown's microfilm collection guide can be divided roughly into the following categories CONTENT MICROFILM # GUIDE Works by RISM number Reels 1- 281 pp. 1 - 38 Copies ofmanuscripts arranged Reels 282-455 pp. 39 - 49 alphabetically by institution I Copies of manuscript collections and Reels 456 - 1103 pp. 49 - 84 . miscellaneous compositions I Operas alphabetical by composer Reels 11 03 - 1126 pp. 85 - 154 I IAnonymous Operas i Reels 1126a - 1126b pp.155-158 I I ILibretti by institution Reels 1127 - 1259 pp. -

MANUAL of POLICY Title Nepotism: Public Officials 1512 Legal

MANUAL OF POLICY Title Nepotism: Public Officials 1512 Legal Authority Approval of the Board of Trustees Page 1 of 2 Date Approved by Board Board Minute Order dated November 26, 2019 I. Purpose The purpose of this policy is to provide provisions regarding nepotism prohibition of public officials as defined by the consanguinity and affinity relationship. II. Policy A. Nepotism Prohibitions Applicable to Public Officials As public officials, the members of the Board of Trustees and the College President are subject to the nepotism prohibitions of Chapter 573 of the Texas Government Code. South Texas College shall not employ any person related within the second degree by affinity (marriage) or within the third degree by consanguinity (blood) to any member of the Board or the College President when the salary, fees, or compensation of the employee is paid from public funds or fees of office. A nepotism prohibition is not applicable to the employment of an individual with the College if: 1) the individual is employed in the position immediately before the election or appointment of the public official to whom the individual is related in a prohibited degree; and 2) that prior employment of the individual is continuous for at least: a. 30 days, if the public official is appointed; b. six months, if the public official is elected at an election other than the general election for state and county officers; or c. one year, if the public official is elected at the general election for state and county officers. If an individual whose employment is not subject to the nepotism prohibition continues in a position, the College President or the member of the Board of Trustees to whom the individual is related in a prohibited degree may not participate in any deliberation or voting on the employment, reemployment, change in status, compensation, or dismissal of the individual if that action applies only to the individual and is not taken regarding a bona fide class or category of employees. -

The Howard Mayer Brown Libretto Collection

• The Howard Mayer Brown Libretto Collection N.B.: The Newberry Library does not own all the libretti listed here. The Library received the collection as it existed at the time of Howard Brown's death in 1993, with some gaps due to the late professor's generosity In loaning books from his personal library to other scholars. Preceding the master inventory of libretti are three lists: List # 1: Libretti that are missing, sorted by catalog number assigned them in the inventory; List #2: Same list of missing libretti as List # 1, but sorted by Brown Libretto Collection (BLC) number; and • List #3: List of libretti in the inventory that have been recataloged by the Newberry Library, and their new catalog numbers. -Alison Hinderliter, Manuscripts and Archives Librarian Feb. 2007 • List #1: • Howard Mayer Brown Libretti NOT found at the Newberry Library Sorted by catalog number 100 BLC 892 L'Angelo di Fuoco [modern program book, 1963-64] 177 BLC 877c Balleto delli Sette Pianeti Celesti rfacsimile 1 226 BLC 869 Camila [facsimile] 248 BLC 900 Carmen [modern program book and libretto 1 25~~ Caterina Cornaro [modern program book] 343 a Creso. Drama per musica [facsimile1 I 447 BLC 888 L 'Erismena [modern program book1 467 BLC 891 Euridice [modern program book, 19651 469 BLC 859 I' Euridice [modern libretto and program book, 1980] 507 BLC 877b ITa Feste di Giunone [facsimile] 516 BLC 870 Les Fetes d'Hebe [modern program book] 576 BLC 864 La Gioconda [Chicago Opera program, 1915] 618 BLC 875 Ifigenia in Tauride [facsimile 1 650 BLC 879 Intermezzi Comici-Musicali -

Third Degree of Consanguinity

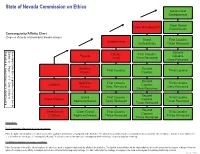

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

Documents, Part VIII

Sec. viIi CONTENTS vIiI–1 PART VIII. GLOSSATORS: MARRIAGE CONTENTS A. GRATIAN OF BOLOGNA, CONCORDANCE OF DISCORDANT CANONS, C.27 q.2 .............VIII–2 B. PETER LOMBARD, FOUR BOOKS OF SENTENCES, 4.26–7 ...................................................VIII–12 C. DECRETALS OF ALEXANDER III (1159–1181) AND INNOCENT III (1198–1216) 1B. Veniens ... (before 1170), ItPont 3:404 .....................................................................................VIII–16 2. Sicut romana (1173 or 1174), 1 Comp. 4.4.5(7) ..........................................................................VIII–16 3. Ex litteris (1175 X 1181), X 4.16.2..............................................................................................VIII–16 4. Licet praeter solitum (1169 X 1179, probably 1176 or1177), X 4.4.3.........................................VIII–17 5. Significasti (1159 X 1181), 1 Comp. 4.4.6(8)..............................................................................VIII–18 6 . Sollicitudini (1166 X 1181), 1 Comp. 4.5.4(6) ............................................................................VIII–19 7 . Veniens ad nos (1176 X 1181), X 4.1.15 .....................................................................................VIII–19 8m. Tuas dutu (1200) .......................................................................................................................VIII–19 9 . Quod nobis (1170 or 1171), X 4.3.1 ............................................................................................VIII–19 10 . Tuae nobis