© Copyright 2014 Morgan E. Palmer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Perspective on the Early Roman Dictatorship, 501-300 B.C

A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. BY Jeffrey A. Easton Submitted to the graduate degree program in Classics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts. Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Committee Members Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date defended: April 26, 2010 The Thesis Committee for Jeffrey A. Easton certifies that this is the approved Version of the following thesis: A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. Committee: Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date approved: April 27, 2010 ii Page left intentionally blank. iii ABSTRACT According to sources writing during the late Republic, Roman dictators exercised supreme authority over all other magistrates in the Roman polity for the duration of their term. Modern scholars have followed this traditional paradigm. A close reading of narratives describing early dictatorships and an analysis of ancient epigraphic evidence, however, reveal inconsistencies in the traditional model. The purpose of this thesis is to introduce a new model of the early Roman dictatorship that is based upon a reexamination of the evidence for the nature of dictatorial imperium and the relationship between consuls and dictators in the period 501-300 BC. Originally, dictators functioned as ad hoc magistrates, were equipped with standard consular imperium, and, above all, were intended to supplement consuls. Furthermore, I demonstrate that Sulla’s dictatorship, a new and genuinely absolute form of the office introduced in the 80s BC, inspired subsequent late Republican perceptions of an autocratic dictatorship. -

11Ffi ELOGIA of the AUGUSTAN FORUM

THEELOGIA OF THE AUGUSTAN FORUM 11ffi ELOGIA OF THE AUGUSTAN FORUM By BRAD JOHNSON, BA A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Brad Johnson, August 2001 MASTER OF ARTS (2001) McMaster University (Classics) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Elogia of the Augustan Forum AUTHOR: Brad Johnson, B.A. (McMaster University), B.A. Honours (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Claude Eilers NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 122 II ABSTRACT The Augustan Forum contained the statues offamous leaders from Rome's past. Beneath each statue an inscription was appended. Many of these inscriptions, known also as elogia, have survived. They record the name, magistracies held, and a brief account of the achievements of the individual. The reasons why these inscriptions were included in the Forum is the focus of this thesis. This thesis argues, through a detailed analysis of the elogia, that Augustus employed the inscriptions to propagate an image of himself as the most distinguished, and successful, leader in the history of Rome. III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Claude Eilers, for not only suggesting this topic, but also for his patience, constructive criticism, sense of humour, and infinite knowledge of all things Roman. Many thanks to the members of my committee, Dr. Evan Haley and Dr. Peter Kingston, who made time in their busy schedules to be part of this process. To my parents, lowe a debt that is beyond payment. Their support, love, and encouragement throughout the years is beyond description. -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

West Asian Geopolitics and the Roman Triumph A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Parading Persia: West Asian Geopolitics and the Roman Triumph A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Carly Maris September 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Michele Salzman, Chairperson Dr. Denver Graninger Dr. Thomas Scanlon Copyright by Carly Maris 2019 The Dissertation of Carly Maris is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements Thank you so much to the following people for your continued support: Dan (my love), Mom, Dad, the Bellums, Michele, Denver, Tom, Vanessa, Elizabeth, and the rest of my friends and family. I’d also like to thank the following entities for bringing me joy during my time in grad school: The Atomic Cherry Bombs, my cats Beowulf and Oberon, all the TV shows I watched and fandoms I joined, and my Twitter community. iv ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Parading Persia: West Asian Geopolitics and The Roman Triumph by Carly Maris Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in History University of California, Riverside, September 2019 Dr. Michele Salzman, Chairperson Parading Persia: West Asian Geopolitics and the Roman Triumph is an investigation into East-West tensions during the first 500 years of Roman expansion into West Asia. The dissertation is divided into three case studies that: (1) look at local inscriptions and historical accounts to explore how three individual Roman generals warring with the dominant Asian-Persian empires for control over the region negotiated -

The Recollections of Encolpius

The Recollections of Encolpius ANCIENT NARRATIVE Supplementum 2 Editorial Board Maaike Zimmerman, University of Groningen Gareth Schmeling, University of Florida, Gainesville Heinz Hofmann, Universität Tübingen Stephen Harrison, Corpus Christi College, Oxford Costas Panayotakis (review editor), University of Glasgow Advisory Board Jean Alvares, Montclair State University Alain Billault, Université Jean Moulin, Lyon III Ewen Bowie, Corpus Christi College, Oxford Jan Bremmer, University of Groningen Ken Dowden, University of Birmingham Ben Hijmans, Emeritus of Classics, University of Groningen Ronald Hock, University of Southern California, Los Angeles Niklas Holzberg, Universität München Irene de Jong, University of Amsterdam Bernhard Kytzler, University of Natal, Durban John Morgan, University of Wales, Swansea Ruurd Nauta, University of Groningen Rudi van der Paardt, University of Leiden Costas Panayotakis, University of Glasgow Stelios Panayotakis, University of Groningen Judith Perkins, Saint Joseph College, West Hartford Bryan Reardon, Professor Emeritus of Classics, University of California, Irvine James Tatum, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire Alfons Wouters, University of Leuven Subscriptions Barkhuis Publishing Zuurstukken 37 9761 KP Eelde the Netherlands Tel. +31 50 3080936 Fax +31 50 3080934 [email protected] www.ancientnarrative.com The Recollections of Encolpius The Satyrica of Petronius as Milesian Fiction Gottskálk Jensson BARKHUIS PUBLISHING & GRONINGEN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY GRONINGEN 2004 Bókin er tileinkuð -

An Encoded Saturnian Theme Peter Mark Adams

The Sola-Busca Tarocchi An Encoded Saturnian Theme Peter Mark Adams The Sola-Busca is a Ferrarese tarocchi produced at the court of the House of Este, Dukes of Ferrara, Reggio and Modena, and dating from 1491. It is the earliest complete deck of tarocchi cards in existence and its fine detail is attributable to its production from copper engraving plates. The Sola-Busca disguises its true import beneath historical narratives derived from Plutarch, Livy and the Alexander Romance literary tradition; but this carefully prepared ‘surface’ has been rendered unstable and polysemous by the systematic use of ambiguity in the spelling of names and the presence of symbolic counters that point towards deeper, occulted levels of meaning. Trump XVIII Lentulo depicts a figure placing a large, freestanding liturgical candle upon an altar with his left hand, whilst his right hand grips his beard. The figure is richly dressed in a long, single-piece gown whose opulence stands out amongst the austere military-style dress of the majority of trumps. The strange arrangement of the head covering is suggestive of an ancient cap known as a pilleus rather than hair. What does this attention grabbing display portend? In Book XIV of Martial’s Epigrams, On the Presents Made to Guests at Feasts, we learn, “Now, while the knights and the lordly senators delight in the festive robe (Latin: synthesibus), and the cap of liberty (Latin: pillea) is assumed by our Jupiter; and while the slave, as he rattles the dice-box, has no fear of the Aedile … what can I do better, Saturn, on these days of pleasure, which your son himself has consecrated to you”. -

Copyrighted Material

CHAPTER ONE i Archaeological Sources Maria Kneafsey Archaeology in the city of Rome, although complicated by the continuous occupation of the site, is blessed with a multiplicity of source material. Numerous buildings have remained above ground since antiquity, such as the Pantheon, Trajan’s Column, temples and honorific arches, while exten- sive remains below street level have been excavated and left on display. Nearly 13 miles (19 kilometers) of city wall dating to the third century CE, and the arcades of several aqueducts are also still standing. The city appears in ancient texts, in thousands of references to streets, alleys, squares, fountains, groves, temples, shrines, gates, arches, public and private monuments and buildings, and other toponyms. Visual records of the city and its archaeology can be found in fragmentary ancient, medieval, and early modern paintings, in the maps, plans, drawings, and sketches made by architects and artists from the fourteenth century onwards, and in images captured by the early photographers of Rome. Textual references to the city are collected together and commented upon in topographical dictionaries, from Henri Jordan’s Topographie der Stadt Rom in Alterthum (1871–1907) and Samuel Ball Platner and Thomas Ashby’s Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (1929), to Roberto Valentini and Giuseppe Zucchetti’s Codice Topografico della Città di Roma (1940–53), the new topographical dictionary published in 1992 by Lawrence RichardsonCOPYRIGHTED Jnr and the larger,MATERIAL more comprehensive Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae (LTUR) (1993–2000), edited by Margareta Steinby (see also LTURS). Key topographical texts include the fourth‐century CE Regionary Catalogues (the Notitia Dignitatum and A Companion to the City of Rome, First Edition. -

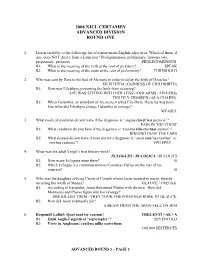

2008 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2008 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Listen carefully to the following list of synonymous English adjectives. Which of them, if any, does NOT derive from a Latin root? Prolegomenous, preliminary, introductory, preparatory, prefatory PROLEGOMENOUS B1: What is the meaning of the verb at the root of prefatory? SPEAK B2: What is the meaning of the noun at the root of preliminary? THRESHOLD 2. Who was sent by Hera to the bed of Alcmene in order to delay the birth of Heracles? EILEITHYIA (GODDESS OF CHILDBIRTH) B1: How was Eileithyia preventing the birth from occuring? SHE WAS SITTING WITH HER LEGS (AND ARMS / FINGERS) TIGHTLY CROSSED (AS A CHARM). B2: When Galanthis, an attendant of Alcmene, tricked Eileithyia, Heracles was born. Into what did Eileithyia change Galanthis in revenge? WEASEL 3. What medical condition do you have if the diagnosis is “angina (ăn-jī΄nƏ) pectoris”? PAIN IN THE CHEST B1: What condition do you have if the diagnosis is “tinnitus (tĭn-eye-tus) aurium”? RINGING IN/OF THE EARS B2: What disease do you have if your doctor’s diagnosis is “sacer (săs΄Ər) morbus” or “morbus caducus”? EPILEPSY 4. What was the adult Vergil’s first literary work? ECLOGUES / BUCOLICA / BUCOLICS B1: How many Eclogues were there? 10 B2: Which Eclogue is a commiseration to Cornelius Gallus on the loss of his mistress? 10 5. Who was the daughter of King Creon of Corinth whom Jason wanted to marry, thereby incurring the wrath of Medea? GLAUCE / CREUSA B1: According to Euripides, Jason threatened Medea with divorce. How did Mermerus and Pheres figure into her revenge? SHE KILLED THEM / THEY TOOK THE POISONED ROBE TO GLAUCE. -

The LEGACY of CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS in the AMERICAS New Nations and a Transatlantic Discourse of Empire

The LEGACY of CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS in the AMERICAS New Nations and a Transatlantic Discourse of Empire Elise Bartosik-Vélez The Legacy of Christopher Columbus in the Americas The LEGACY of CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS in the AMERICAS New Nations and a Transatlantic Discourse of Empire Elise Bartosik-Vélez Vanderbilt University Press NASHVILLE © 2014 by Vanderbilt University Press Nashville, Tennessee 37235 All rights reserved First printing 2014 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file LC control number 2013007832 LC classification number e112 .b294 2014 Dewey class number 970.01/5 isbn 978-0-8265-1953-5 (cloth) isbn 978-0-8265-1955-9 (ebook) For Bryan, Sam, and Sally Contents Acknowledgments ................................. ix Introduction .......................................1 chapter 1 Columbus’s Appropriation of Imperial Discourse ............................ 15 chapter 2 The Incorporation of Columbus into the Story of Western Empire ................. 44 chapter 3 Columbus and the Republican Empire of the United States ............................. 66 chapter 4 Colombia: Discourses of Empire in Spanish America ............................ 106 Conclusion: The Meaning of Empire in Nationalist Discourses of the United States and Spanish America ........................... 145 Notes ........................................... 153 Works Cited ..................................... 179 Index ........................................... 195 Acknowledgments any people helped me as I wrote this book. Michael Palencia-Roth has been an unfailing mentor and model of Methical, rigorous scholarship and human compassion. I am grate- ful for his generous help at many stages of writing this manu- script. I am also indebted to my friend Christopher Francese, of the Department of Classical Studies at Dickinson College, who has never hesitated to answer my queries about pretty much any- thing related to the classical world. -

Howard Mayer Brown Microfilm Collection Guide

HOWARD MAYER BROWN MICROFILM COLLECTION GUIDE Page individual reels from general collections using the call number: Howard Mayer Brown microfilm # ___ Scope and Content Howard Mayer Brown (1930 1993), leading medieval and renaissance musicologist, most recently ofthe University ofChicago, directed considerable resources to the microfilming ofearly music sources. This collection ofmanuscripts and printed works in 1700 microfilms covers the thirteenth through nineteenth centuries, with the bulk treating the Medieval, Renaissance, and early Baroque period (before 1700). It includes medieval chants, renaissance lute tablature, Venetian madrigals, medieval French chansons, French Renaissance songs, sixteenth to seventeenth century Italian madrigals, eighteenth century opera libretti, copies ofopera manuscripts, fifteenth century missals, books ofhours, graduals, and selected theatrical works. I Organization The collection is organized according to the microfilm listing Brown compiled, and is not formally cataloged. Entries vary in detail; some include RISM numbers which can be used to find a complete description ofthe work, other works are identified only by the library and shelf mark, and still others will require going to the microfilm reel for proper identification. There are a few microfilm reel numbers which are not included in this listing. Brown's microfilm collection guide can be divided roughly into the following categories CONTENT MICROFILM # GUIDE Works by RISM number Reels 1- 281 pp. 1 - 38 Copies ofmanuscripts arranged Reels 282-455 pp. 39 - 49 alphabetically by institution I Copies of manuscript collections and Reels 456 - 1103 pp. 49 - 84 . miscellaneous compositions I Operas alphabetical by composer Reels 11 03 - 1126 pp. 85 - 154 I IAnonymous Operas i Reels 1126a - 1126b pp.155-158 I I ILibretti by institution Reels 1127 - 1259 pp. -

The Howard Mayer Brown Libretto Collection

• The Howard Mayer Brown Libretto Collection N.B.: The Newberry Library does not own all the libretti listed here. The Library received the collection as it existed at the time of Howard Brown's death in 1993, with some gaps due to the late professor's generosity In loaning books from his personal library to other scholars. Preceding the master inventory of libretti are three lists: List # 1: Libretti that are missing, sorted by catalog number assigned them in the inventory; List #2: Same list of missing libretti as List # 1, but sorted by Brown Libretto Collection (BLC) number; and • List #3: List of libretti in the inventory that have been recataloged by the Newberry Library, and their new catalog numbers. -Alison Hinderliter, Manuscripts and Archives Librarian Feb. 2007 • List #1: • Howard Mayer Brown Libretti NOT found at the Newberry Library Sorted by catalog number 100 BLC 892 L'Angelo di Fuoco [modern program book, 1963-64] 177 BLC 877c Balleto delli Sette Pianeti Celesti rfacsimile 1 226 BLC 869 Camila [facsimile] 248 BLC 900 Carmen [modern program book and libretto 1 25~~ Caterina Cornaro [modern program book] 343 a Creso. Drama per musica [facsimile1 I 447 BLC 888 L 'Erismena [modern program book1 467 BLC 891 Euridice [modern program book, 19651 469 BLC 859 I' Euridice [modern libretto and program book, 1980] 507 BLC 877b ITa Feste di Giunone [facsimile] 516 BLC 870 Les Fetes d'Hebe [modern program book] 576 BLC 864 La Gioconda [Chicago Opera program, 1915] 618 BLC 875 Ifigenia in Tauride [facsimile 1 650 BLC 879 Intermezzi Comici-Musicali -

Histoire Romaine

HISTOIRE ROMAINE EUGÈNE TALBOT PARIS - 1875 AVANT-PROPOS PREMIÈRE PARTIE. — ROYAUTÉ CHAPITRE PREMIER. - CHAPITRE II. - CHAPITRE III. SECONDE PARTIE. — RÉPUBLIQUE CHAPITRE PREMIER. - CHAPITRE II. - CHAPITRE III. - CHAPITRE IV. - CHAPITRE V. - CHAPITRE VI. - CHAPITRE VII. - CHAPITRE VIII. - CHAPITRE IX. - CHAPITRE X. - CHAPITRE XI. - CHAPITRE XII. - CHAPITRE XIII. - CHAPITRE XIV. - CHAPITRE XV. - CHAPITRE XVI. - CHAPITRE XVII. - CHAPITRE XVIII. - CHAPITRE XIX. - CHAPITRE XX. - CHAPITRE XXI. - CHAPITRE XXII. TROISIÈME PARTIE. — EMPIRE CHAPITRE PREMIER. - CHAPITRE II. - CHAPITRE III. AVANT-PROPOS. LES découvertes récentes de l’ethnographie, de la philologie et de l’épigraphie, la multiplicité des explorations dans les diverses contrées du monde connu des anciens, la facilité des rapprochements entre les mœurs antiques et les habitudes actuelles des peuples qui ont joué un rôle dans le draine du passé, ont singulièrement modifié la physionomie de l’histoire. Aussi une révolution, analogue à celle que les recherches et les œuvres d’Augustin Thierry ont accomplie pour l’histoire de France, a-t-elle fait considérer sous un jour nouveau l’histoire de Rome et des peuples soumis à son empire. L’officiel et le convenu font place au réel, au vrai. Vico, Beaufort, Niebuhr, Savigny, Mommsen ont inauguré ou pratiqué un système que Michelet, Duruy, Quinet, Daubas, J.-J. Ampère et les historiens actuels de Rome ont rendu classique et populaire. Nous ne voulons pas dire qu’il ne faut pas recourir aux sources. On ne connaît l’histoire romaine que lorsqu’on a lu et étudié Salluste, César, Cicéron, Tite-Live, Florus, Justin, Velleius, Suétone, Tacite, Valère Maxime, Cornelius Nepos, Polybe, Plutarque, Denys d’Halicarnasse, Dion Cassius, Appien, Aurelius Victor, Eutrope, Hérodien, Ammien Marcellin, Julien ; et alors, quand on aborde, parmi les modernes, outre ceux que nous avons nommés, Machiavel, Bossuet, Saint- Évremond, Montesquieu, Herder, on comprend l’idée, que les Romains ont développée dans l’évolution que l’humanité a faite, en subissant leur influence et leur domination.