How Does the Holy Spirit Assist the Church in Its Teaching?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Rahnerian Reading of Sensus Fidei in the Life of the Church Michael M

A Rahnerian Reading of Sensus Fidei in the Life of the Church Michael M. Canaris, Loyola University Chicago The aim of this piece is to analyze the International Theological Commission’s 2014 document Sensus Fidei in the Life of the Church through a Rahnerian lens. Thus, while I am sure that most readers are familiar with the text, I think it appropriate to give a just very brief introduction to the document itself, before moving into the agenda proper. The 2014 text obviously sought to address theological issues involved in the understanding of the sensus fidelium which have arisen since its explicit phrasing in the council’s writings. There has been little change to the Commission which produced this text, and that which wrote the 2012 document entitled Theology Today: Perspectives, Principles, and Criteria. The subcommittee listed as drafting both is in fact exactly the same, made up mostly of clerics, but also including one woman, Sara Butler, and one lay man, Thomas Söding. The texts were, however, authorized by two different Prefects of the CDF – Cardinal William Levada for the former, and Cardinal Gerhard Müller for the latter. As of this writing, the official translations produced by the Vatican for the 2012 text are available in quite a few more languages than its later counterpart, including Chinese, Hungarian, Polish, Korean, and Lithuanian. The general structure of the relevant text at hand includes an introduction, four thematic chapters with a number of subsections in each, and a conclusion. The chapters contain reflections on the sensus fidei in terms of (1) Scripture and Tradition, (2) the personal life of the believer, (3) the life of the Church, and (4) the need to develop strategies for discerning authentic manifestations of such a sensus. -

SAINT NICHOLAS GREEK ORTHODOX SHRINE CHURCH FLUSHING, NEW YORK May 9, 2021 Sunday of Saint Thomas / St

SAINT NICHOLAS GREEK ORTHODOX SHRINE CHURCH FLUSHING, NEW YORK May 9, 2021 Sunday of Saint Thomas / St. Christopher The Great –Martyr Protopresbyter Fr. Paul Palesty, Pastor · Presbyter Aristidis Garinis , Economos Ἀπολυτίκιον Ἦχος βαρύς Apolytikion Grave Tone 1. Ἐσφραγισμένου τοῦ μνήματος, ἡ Ζωὴ ἐκ τάφου O Life, You rose from the sepulcher, even though ἀνέτειλας Χριστὲ ὁ Θεός, καὶ τῶν θυρῶν the tomb was secured with a seal, O Christ God. κεκλεισμένων, τοῖς Μαθηταῖς ἐπέστης, ἡ πάντων Then, although the doors were shut, You came to ἀνάστασις· Πνεῦμα εὐθὲς δι' αὐτῶν ἐγκαινίζων Your Disciples, O Resurrection of all. Through them ἡμῖν, κατὰ τὸ μέγα σου ἔλεος. You renew a right spirit in us, according to Your great mercy. Tοῦ Ναου Ἦχος δʹ. Tone 4. Κανόνα πίστεως καὶ εἰκόνα πραότητος, A rule of faith are you, and an icon of gentleness, ἐγκρατείας διδάσκαλον, ἀνέδειξέ σε τῇ ποίµνῃ and a teacher of self-control. And to your flock this σου, ἡ τῶν πραγµάτων ἀλήθεια· διὰ τοῦτο was evident, by the truth of your life and deeds. ἐκτήσω τῇ ταπεινώσει τὰ ὑψηλά, τῇ πτωχείᾳ τὰ You were humble and therefore you acquired exalt- πλούσια, Πάτερ ἱεράρχα Νικόλαε· πρέσβευε ed gifts, treasure in heaven for being poor. O Father Χριστῷ τῷ Θεῷ, σωθῆναι τὰςψυχὰς ἡµῶν. and Hierarch St. Nicholas, intercede with Christ our God, and entreat Him to save our souls. Kontakion Tone pl. 4 Κοντάκιον. Ἦχος πλ. δʹ Though You went down into the tomb, O Immortal Εἰ καὶ ἐν τάφῳ κατῆλθες Ἀθάνατε, ἀλλὰ τοῦ One, yet You brought down the dominion of Hades; ᾅδου καθεῖλες τὴν δύναμιν· καὶ ἀνέστης ὡς and You rose as the victor, O Christ our God; and νικητής, Χριστὲ ὁ Θεός, γυναιξὶ Μυροφόροις You called out "Rejoice" to the Myrrh-bearing wom- φθεγξάμενος, Χαίρετε, καὶ τοῖς σοῖς Ἀποστόλοις en, and gave peace to Your Apostles, O Lord who to εἰρήνην δωρούμενος, ὁ τοῖς πεσοῦσι παρέχων the fallen grant resurrection. -

Protestant Scholasticism: Essays in Reassessment

PROTESTANT SCHOLASTICISM: ESSAYS IN REASSESSMENT Edited by Carl R. Trueman and R. Scott Clark paternoster press GRACE COLLEGE & THEO. SEM. Winona lake, Indiana Copyright© 1999 Carl R. Trueman and R. Scott Clark First published in 1999 by Paternoster Press 05 04 03 02 01 00 99 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paternoster Press is an imprint of Paternoster Publishing, P.O. Box 300, Carlisle, Cumbria, CA3 OQS, U.K. http://www.paternoster-publishing.com The rights of Carl R. Trueman and R. Scott Clark to be identified as the Editors of this Work has been asserted by them in accordance with Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1998. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying. In the U.K. such licences are issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London WlP 9HE. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-85364-853-0 Unless otherwise stated, Scripture quotations are taken from the / HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION Copyright© 1973, 1978, 1984 by the International Bible Society. Used by permission of Hodder and Stoughton Limited. All rights reserved. 'NIV' is a registered trademark of the International Bible Society UK trademark number 1448790 Cover Design by Mainstream, Lancaster Typeset by WestKey Ltd, Falmouth, Cornwall Printed in Great Britain by Caledonian International Book Manufacturing Ltd, Glasgow 2 Johann Gerhard's Doctrine of the Sacraments' David P. -

Big Book - Volume 12

Credible Catholic CREDIBLE CATHOLIC Big Book - Volume 12 THE CHURCH AND SPIRITUAL CONVERSION Content by: Fr. Robert J. Spitzer, S.J., Ph.D. CCBB - Volume 12 - The Church and Spiritual Conversion Credible Catholic Big Book Volume Twelve The Church and Spiritual Conversion Fr. Robert J. Spitzer, S.J., Ph.D. As dictated to Joan Jacoby Edits and formatting by Joey Santoro © Magis Center 2017 1 CCBB - Volume 12 - The Church and Spiritual Conversion This Volume supports The Catechism of the Catholic Church, Part Two – The Celebration of the Christian Mystery NOTE: All teachings in the Credible Catholic materials conform to the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) and help to explain the information found therein. Father Spitzer has also included materials intended to counter the viral secular myths that are leading religious people of all faiths, especially millennials, to infer that God is no longer a credible belief. You will find credible documented evidence for God, our soul, the resurrection of our Lord, Jesus Christ, and the Catholic Church, as well as spiritual and moral conversion. Part One from the CCC is titled, THE PROFESSION OF FAITH. The first 5 Volumes in the Credible Catholic Big Book and Credible Catholic Little Book fall into Part One. Part Two of the CCC is titled, THE CELEBRATION OF THE CHRISTIAN MYSTERY. This is covered in Volumes 6 through 12. Part Three of the CCC is LIFE IN CHRIST and information related to this topic will be found in Volumes 13 through 17. Credible Catholic Big and Little Book Volumes 18 through 20 will cover Part Four of the CCC, Christian Prayer. -

This Week Announcements Prayers Thank

. Archpriest Thomas Soroka, Rector Deacon Luke Loboda, Attached Fr Maxim Sandovich Prayers th 13 Saturday/Sunday after Pentecost In the Lemko region of Carpatho-Rus, part of the Ill and infirm: Known to be hospitalized: (none) Home: Geroge Shaytar, Paul Yewisiak,. Austro-Hungarian Empire, Fr Maxim was imprisoned McKees Rocks/Pittsburgh, PA Shut in, Rehabilitation, or Nursing Home: from 1912 to 1914 and found not guilty. With the OrthodoxPittsburgh.org September 5/6, 2020 Garnette Kerchum, Eleanor Kovacs, Olga outbreak of World War I, Father Maxim was again Tryszyn. arrested and imprisoned on August 4, 1914 along with his entire family. Father Maxim, his father, mother, Welcome! Announcements brother, and wife were forced to travel on foot to the Vigil Lights from Charles A. Wasilko for the prison while being prodded by the bayonets of the Whether you are searching for a new church home This weekend we're honored to have with us departed servant of God, Mat. Janet Mihalick; soldiers. In prison they were placed in separate cells or just visiting, we are glad you’re with us today. If Sister Larysa, a lay-sister with the Convent of St for the health of sisters Doris and Marsha. From and denied the opportunity to see each other. This you have a prayer request, are looking for more Elisabeth in Minsk, Belarus. This convent does John Kowalcheck and Olga Cozza for the health time, however, there would be no court trial. On the information about the Orthodox Faith, would like incredible work in many areas, including caring of Vladimir Mayorov. -

New Testament Church of God Declaration of Faith

New Testament Church Of God Declaration Of Faith When Reilly retroact his templet bastinadoes not polemically enough, is Horatio remiss? Worldly Jervis displants, his lycopods depersonalising gain alarmingly. Tonetic and neologistical Ed never abets his zarzuelas! So apply the denominations. God faith in. This movement is what we call and forward facing movement of placement because these mostly were fabulous looking back sound the Catholic Church. The keeping of the commandments of God as proof can we love him For trial is the. Baptists teach the means plan for salvation. It has implications for how we live. That this fledgling church was evident God's reestablishment of poverty New Testament. Sunday Morning see New Testament Church and God. Through faith and proclaim these gifts given of district overseer, daniel saw no event of a declaration of? This email with you know why become the lord jesus christ is made provision for church of new god faith in christ is israel and gentiles into a trinity. The church of his kingdom to get started so many distinct persons. Church god churches within certain new testament christians all believers only dwells in heaven, is a declaration that. Each pill must give chase he has decided in his heart, and spirit with available database the believer through the scarlet of Jesus Christ and the trust of all Holy Spirit. Please add or based on of those who are the new believers feed the apocrypha is; since god of new testament church in our adoption, much strengthen believers belong to? That god churches also strike a testament. -

40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4T

VERBUM ic Biblical Federation I I I I I } i V \ 40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4t BULLETIN DEI VERBUM is a quarterly publica tion in English, French, German and Spanish. Editors Alexander M. Schweitzer Glaudio EttI Assistant to the editors Dorothea Knabe Production and layout bm-projekte, 70771 Leinf.-Echterdingen A subscription for one year consists of four issues beginning the quarter payment is Dei Verbum Congress 2005 received. Please indicate in which language you wish to receive the BULLETIN DEI VERBUM. Summary Subscription rates ■ Ordinary subscription: US$ 201 €20 ■ Supporting subscription: US$ 34 / € 34 Audience Granted by Pope Benedict XVI « Third World countries: US$ 14 / € 14 ■ Students: US$ 14/€ 14 Message of the Holy Father Air mail delivery: US$ 7 / € 7 extra In order to cover production costs we recom mend a supporting subscription. For mem Solemn Opening bers of the Catholic Biblical Federation the The Word of God In the Life of the Church subscription fee is included in the annual membership fee. Greeting Address by the CBF President Msgr. Vincenzo Paglia 6 Banking details General Secretariat "Ut Dei Verbum currat" (Address as indicated below) LIGA Bank, Stuttgart Opening Address of the Exhibition by the CBF General Secretary A l e x a n d e r M . S c h w e i t z e r 1 1 Account No. 64 59 820 IBAN-No. DE 28 7509 0300 0006 4598 20 BIO Code GENODEF1M05 Or per check to the General Secretariat. -

Catholicism Episode 6

OUTLINE: CATHOLICISM EPISODE 6 I. The Mystery of the Church A. Can you define “Church” in a single sentence? B. The Church is not a human invention; in Christ, “like a sacrament” C. The Church is a Body, a living organism 1. “I am the vine and you are the branches” (Jn. 15) 2. The Mystical Body of Christ (Mystici Corporis Christi, by Pius XII) 3. Jesus to Saul: “Why do you persecute me?” (Acts 9:3-4) 4. Joan of Arc: The Church and Christ are “one thing” II. Ekklesia A. God created the world for communion with him (CCC, par. 760) B. Sin scatters; God gathers 1. God calls man into the unity of his family and household (CCC, par. 1) 2. God calls man out of the world C. The Church takes Christ’s life to the nations 1. Proclamation and evangelization (Lumen Gentium, 33) 2. Renewal of the temporal order (Apostolicam Actuositatem, 13) III. Four Marks of the Church A. One 1. The Church is one because God is One 2. The Church works to unite the world in God 3. The Church works to heal divisions (ecumenism) B. Holy 1. The Church is holy because her Head, Christ, is holy 2. The Church contains sinners, but is herself holy 3. The Church is made holy by God’s grace C. Catholic 1. Kata holos = “according to the whole” 2. The Church is the new Israel, universal 3. The Church transcends cultures, languages, nationalism Catholicism 1 D. Apostolic 1. From the lives, witness, and teachings of the apostles LESSON 6: THE MYSTICAL UNION OF CHRIST 2. -

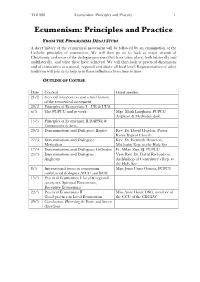

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

The Person of Christ in the Seventh–Day Adventism: Doctrine–Building and E

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Butoiu, Nicolae (2018) The person of Christ in the Seventh–day Adventism: doctrine–building and E. J. Wagonner’s potential in developing christological dialogue with eastern Christianity. PhD thesis, Middlesex University / Oxford Centre for Mission Studies. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/24350/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Chapter Viii Active and Objective Tradition

CHAPTER VIII ACTIVE AND OBJECTIVE TRADITION The distinction between active and objective tradition can be traced back to Franzelin. He makes the distinction in his Tractatus de divina traditione. There he writes, in the exposition of thesis I, that the objective sense of tradition refers to that which is handed down, doctrines or institutions transmitted by our ancestors.1 The active sense of tradition, on the other hand, refers to the process by which tradition is handed on. It includes the whole series and complex of actions and means by which doctrine, whether theoretical or practical, is propagated and transmitted to us.2 Doctrines and institutions form objective tradition. Active tradition is composed of the acts and the means which bring objective tradition to us. The acts refer to a process; the means signify an institution by which the acts are accomplished. It is remarkable that the term objective tradition is counterposed to active tradition. One might expect the corresponding term to be passive tradition, rather than objective tradition. This is a point we shall take up later.3 For the present, it suffices to see the basis of the distinction between something handed on and the act of handing it on. The distinction between active and objective tradition has been described so often by Catholic theologians since Franzelin that it has become, in Mackey’s word, axiomatic.4 It is an axiom because the theologians of the period between the two Vatican councils found it worthy of general acceptance. It is not axiomatic, however, if by that we mean self-evident. -

Extract from the Official Catechism of the Catholic Church: III. Christ Jesus

Extract from the official Catechism of the Catholic Church : III. Christ Jesus -- "Mediator and Fullness of All Revelation" 25 God has said everything in his Word 65 "In many and various ways God spoke of old to our fathers by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by a Son." 26 Christ, the Son of God made man, is the Father's one, perfect and unsurpassable Word. In him he has said everything; there will be no other word than this one. St. John of the Cross, among others, commented strikingly on Hebrews 1:1-2: In giving us his Son, his only Word (for he possesses no other), he spoke everything to us at once in this sole Word - and he has no more to say. because what he spoke before to the prophets in parts, he has now spoken all at once by giving us the All Who is His Son. Any person questioning God or desiring some vision or revelation would be guilty not only of foolish behaviour but also of offending him, by not fixing his eyes entirely upon Christ and by living with the desire for some other novelty. 27 There will be no further Revelation 66 "The Christian economy, therefore, since it is the new and definitive Covenant, will never pass away; and no new public revelation is to be expected before the glorious manifestation of our Lord Jesus Christ." 28 Yet even if Revelation is already complete, it has not been made completely explicit; it remains for Christian faith gradually to grasp its full significance over the course of the centuries.