Download Resource PDF Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4T

VERBUM ic Biblical Federation I I I I I } i V \ 40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4t BULLETIN DEI VERBUM is a quarterly publica tion in English, French, German and Spanish. Editors Alexander M. Schweitzer Glaudio EttI Assistant to the editors Dorothea Knabe Production and layout bm-projekte, 70771 Leinf.-Echterdingen A subscription for one year consists of four issues beginning the quarter payment is Dei Verbum Congress 2005 received. Please indicate in which language you wish to receive the BULLETIN DEI VERBUM. Summary Subscription rates ■ Ordinary subscription: US$ 201 €20 ■ Supporting subscription: US$ 34 / € 34 Audience Granted by Pope Benedict XVI « Third World countries: US$ 14 / € 14 ■ Students: US$ 14/€ 14 Message of the Holy Father Air mail delivery: US$ 7 / € 7 extra In order to cover production costs we recom mend a supporting subscription. For mem Solemn Opening bers of the Catholic Biblical Federation the The Word of God In the Life of the Church subscription fee is included in the annual membership fee. Greeting Address by the CBF President Msgr. Vincenzo Paglia 6 Banking details General Secretariat "Ut Dei Verbum currat" (Address as indicated below) LIGA Bank, Stuttgart Opening Address of the Exhibition by the CBF General Secretary A l e x a n d e r M . S c h w e i t z e r 1 1 Account No. 64 59 820 IBAN-No. DE 28 7509 0300 0006 4598 20 BIO Code GENODEF1M05 Or per check to the General Secretariat. -

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

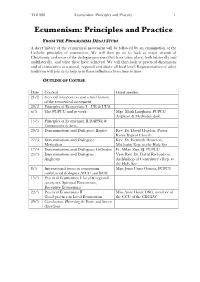

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

THE CORPORAL and SPIRITUAL WORKS of MERCY Sr

Teachings of SCTJM - Sr. Silvia Maria Tarafa, SCTJM RESPONDING TO DIVINE MERCY: THE CORPORAL AND SPIRITUAL WORKS OF MERCY Sr. Silvia Maria Tarafa, SCTJM July 2011 What is Divine Mercy? The message of Divine mercy you have been hearing from my sisters is that we are miserable, weak creatures, and the Lord loves us anyways- because He is merciful. We see his mercy everywhere throughout all the scriptures, through the messages of St. Faustina, Through John Paul II encyclical, “Rich in Mercy,” through the Catechism, through the sacraments,-most especially the mass and confession and by contemplating the pierced Heart of Christ himself. As if these were not enough and to help us to come to Him more, Our Lord opens up five fountains, five vessels as if coming from His five wounds for us to draw from there His mercy. Through these vessels we can “keep coming for graces to the fountain of mercy (Diary 327) These fountains are (1)The Image of Mercy,(2)The Chaplet of mercy- (3)The Feast of Mercy, (4)The Novena to the Divine Mercy and (5) The Three O’clock Hour. And how do we open ourselves up to receive this ocean of mercy. How do we draw the water of His mercy from these fountains? He tells St. Faustina through trust. The graces of My Mercy are drawn by means of one vessel only that is “trust. …The greatest flames of My mercy are burning me I desire to pour them out upon human souls. Oh what pain they cause me when they don’t want to accept them! My daughter do whatever is within your power to spread devotion to My Mercy. -

Ecumenical Councils Preparing for Next Week (Disciple 6–Eucharist 1)

January St. Dominic’s RCIA Program Disciple The Church: 15 History & Teaching 4 Goal • Having switched the Disciple 4 & 5 weeks, we looks at an overview of the Sacraments last week (Disciple 5), and explored the Sacraments of Baptism and Confirmation. These Sacraments are two of the three that initiate us into the Church community, and into Christ’s body and mission. This week we’ll continue to unpack the meaning of Church by looking broadly at its history one the last 2000 years. We’ll also explore it’s role as Teacher. How does the Church function in and through history? How does God walk with the Church through it all? Agenda • Welcome/Housekeeping (10) • Questions & Answers • Introduction to the Rosary (15) Discussion (15): • If the Church is The Body of Christ, what does this mean for Christ’s presence in the world through history and in the world today? • What do I admire about the Catholic Church’s activity in history? Does any part of the Church’s activity in history disturb or upset me? • How do I (might I) listen to what the Church has to say today? What is my approach/attitude to the Church as “Teacher”? • Presentation: The Church: History (35) • Break (10) • Presentation: The Church: Teaching & Belief (30) • Discussion (time permitting): • What is special to this moment in history? • What is the Good News of Christ & the Church that speaks to this moment in history? • How can the body of Christ proclaim & witness the Gospel and walk with others today? Housekeeping Notes • Rite of Acceptance: February 10th at the 11:30am and 5:30 Masses. -

Pastor's Meanderings 10 – 11 December 2016 Third Sunday

PASTOR’S MEANDERINGS 10 – 11 DECEMBER 2016 THIRD SUNDAY OF ADVENT GAUDATE SUNDAY STEWARDSHIP: Each of us has his or her own role to play in the coming of the kingdom of God. John the Baptist was called to be the herald of the Messiah, preparing the way of the Lord. To what is the Lord calling me? St. Teresa of Avila “Patient endurance attaineth to all things.” READINGS FOR FOURTH SUNDAY OF ADVENT 18 DEC ‘16 Is. 7:10-16: King Ahaz of Judah, one of the successors to David and a king who is beset on all sides by enemies and would-be conquerors, is challenged by the prophet Isaiah who holds out a word of hope: ‘The maiden is with child and will give birth to a son… Immanuel, a name which means “god-is-with-us’. That prophecy finds it eventual fulfilment at Bethlehem. Rom. 1:1-7: Paul is writing to relatively new Christians without much background in the Jewish scriptures, trying to introduce them to the character of Jesus as one who has long been predicted to come as the ‘Son of God.’ Mt. 1:18-25: Matthew takes Isaiah’s words about the Lord’s sign to the people that God would always be with them – a child named Immanuel – and applies them to the coming birth of Jesus. St. Athanasius of Alexandria “He became what we are that He might make us what He is.” ICON AT ENTRANCE TO THE CHURCH THE VIRGIN OF THE SIGN Figures with hand raised in prayer, the “Orans” pose, date from earliest Christian art and even before. -

Article Reviews Walter Kasper on the Catholic Church

ecclesiology 14 (2018) 203-211 ECCLESIOLOGY brill.com/ecso Article Reviews ∵ Walter Kasper on the Catholic Church Susan K. Wood Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, usa [email protected] Walter Kasper The Catholic Church: Nature, Reality and Mission, trans. Thomas Hoebel (London and New York: Bloomsbury, T&T Clark, 2015), xviii + 463 pp. isbn 978-1-4411-8709-3 (pbk). $54.95. The Catholic Church: Nature – Reality – Mission, following more than twenty years after Jesus the Christ and The God of Jesus Christ, is the third volume of a trilogy, their Christological unity indicated by their German titles: Jesus Der Christus (1974), Der Gott Jesu Christi (1982) and Die Kirche Jesu Christi (2008). Life had intervened in the interim, first by Kasper’s service as bishop of Rottenburg- Stuttgart (1989–1999), followed by eleven years with the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity (1999–2010) where he was its cardinal prefect from 2001. This interim period also included his work as theological secretary of the Extraordinary Synod (1985) which had identified communio as a central theme and guiding principle of the Second Vatican Council. His life in and for the church had interrupted his theological work on a systematic treatise on the church, fortuitous for an ecclesiology that not only reflects develop- ment since the Second Vatican Council, but also aims to be an existential ec- clesiology relevant for both the individual and society. He comments that an ecclesiology for today must perceive the crisis of the Church manifested by decreasing church attendance, decline in participation in the sacraments, and priest shortages in connection with the crises of today’s world in a post- Constantinian time (p. -

This Article First Presents the Status Questionis of the Issue of Communion for the Remarried Divorcees

EUCHARISTIC COMMUNION FOR THE REMARRIED D IVORCEES: IS AMORIS LAETITIA THE FINAL ANSWER? RAMON D. ECHICA This article first presents the status questionis of the issue of communion for the remarried divorcees. There is an interlocution between the affirmative answer represented by Walter Kasper and the negative answer represented by Carlo Caffara and Gerhard Mueller. The article then offers two theological concepts not explicitly mentioned in Amoris Laetitia to buttress the affirmative answer. INTRODUCTION THE CONTEXT OF THE ISSUE rom the Synod of the Family of 2014, then followed by a bigger Fsynod on the same subject a year after, up to the issuance of the Apostolic Exhortation Amoris Laetitia (AL), what got the most media attention was the issue of the reception of Eucharistic communion by divorcees, whose marriages have never been declared null by the Church and who have entered a second (this time purely civil or state) marriage. The issue became the subject matter of some reasoned theological discourse but also of numerous acrimonious debates. Three German bishops, namely Walter Kasper, Karl Lehman and Oskar Saier were the first prominent hierarchical members who openly raised the issue through a pastoral letter in 1993.1Nothing much came out of it until Pope Francis signaled his 1 Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger thumbed down the proposal in 1994. For a brief history of the earlier attempts to allow divorcees to receive communion, see Lisa Duffy, “Pope Benedict Already Settled the Question of Communion for the Hapág 13, No. 1-2 (2016) 49-69 EUCHARISTIC COMMUNION FOR THE REMARRIED DIVORCESS openness to rethink the issue. -

Works of Mercy Social Justice

Formative Parenting Cultivating Character in Children A Ministry of the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, Immaculata, Pennsylvania WORKS OF MERCY & SOCIAL JUSTICE English writer John Heywood remarked: “They do not love that do not show their love.” In response, many of us wonder, how would one show love? As children, we learn how to transfer the abstract concept of love into practical and observable actions through the teaching and example of our parents. It is a parent’s major responsibility. This newsletter, one of a six-part series, presents the WORKS OF MERCY and the PRINCIPLES OF CATHOLIC SOCIAL TEACHING as formulas for love. Other newsletters spotlight Spirituality of Communion and the Ten Commandments as expressions of love. WORKS OF MERCY Generations of Catholics can recite from memory the Spiritual and Corporal Works of Mercy. These are basic charitable actions that aid another person in physical, or spiritual ways, such as feeding the hungry and visiting the sick or in spiritual, psychological ways such as counseling the doubtful. When these works are demonstrated in behaviors, love becomes visible. The corporal works of mercy implore us to feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, clothe the naked, help those imprisoned, shelter the homeless, care for the sick, and bury the dead. The spiritual works of mercy encourage us to counsel the sinner, share knowledge of God with others, advise the doubtful, comfort the sorrowful, bear wrongs patiently, forgive all injuries, and to pray for the living and for the dead. Teach both the literal and the creative sense of each Work of Mercy. -

Oblates to Celebrate Life of Mother Mary Lange,Special Care Collection

Oblates to celebrate life of Mother Mary Lange More than 30 years before the Emancipation Proclamation, Mother Mary Lange fought to establish the first religious order for black women and the first black Catholic school in the United States. To honor the 126th anniversary of their founder’s death, the Oblate Sisters of Providence have planned a Feb. 3 Mass of Thanksgiving at 1 p.m., which will be celebrated by Cardinal William H. Keeler in the Our Lady of Mount Providence Convent Chapel in Catonsville. The Mass will be followed by a reception, offering guests the opportunity to view Mother Mary Lange memorabilia. A novena will also be held Jan. 25-Feb. 2 in the chapel. Sister M. Virginie Fish, O.S.P., and several of her colleagues in the Archdiocese of Baltimore have devoted nearly 20 years to working on the cause of canonization for Mother Mary Lange, who, along with Father James Hector Joubert, S.S., founded the Oblate Sisters in 1829. With the help of two other black women, Mother Mary Lange also founded St. Frances Academy, Baltimore, in 1828, which is the first black Catholic school in the country and still in existence. Sister Virginie said the sisters see honoring Mother Mary Lange as a fitting way to kick-start National Black History Month. Father John Bowen, S.S., postulator for Mother Mary Lange’s cause, completed the canonization application three years ago and sent it to Rome, where it is currently under review. There is no timetable for the Vatican to complete or reject sainthood for Mother Mary Lange, Father Bowen said. -

Bishop Celebrates 50Th Anniversary Mass at Marian High School

September 21, 2014 Think Green 50¢ Recycle Volume 88, No. 30 Go Green todayscatholicnews.org Serving the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend Go Digital ’’ RED MASS OPEN TO TTODAYODAYSS CCATHOLICATHOLIC ALL THE FAITHFUL A Red Mass will be held Wednesday, Sept. 24, at 5:30 p.m. Bishop celebrates 50th anniversary at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Fort Wayne. The South Bend area Mass at Marian High School Red Mass will be Monday, Oct. 6, at 5:15 p.m. at the BY CHRISTOPHER LUSHIS Basilica of the Sacred Heart MISHAWAKA — “Put out into the See pages 13-14 deep!” announced Bishop Kevin C. Rhoades to the Marian High School community during their golden anni- versary Mass on Sept. 4. This joyous occasion commemorated the com- Tribute pletion of the endeavor undertaken by the sixth bishop of the Diocese Father Chrobot dies of Fort Wayne-South Bend, Bishop Leo A. Pursley, to construct a sec- Page 3 ond Catholic high school to serve the needs of the South Bend and Mishawaka area in 1964. Present for this special Mass Congregation were Benedictine Father Jonathan Fassero, a member of the first gradu- of Holy Cross ating class of 1968 from Marian, and Msgr. Michael Heintz, rector of Six make final vows, St. Matthew Cathedral and a 1985 graduate. Also in attendance were ordained deacons priests from St. Jude, St. Anthony de KEVIN HAGGENJOS Page 5 Padua, St. Bavo, St. Matthew and St. th Thomas Parishes, as well as priests Bishop Kevin C. Rhoades celebrates Mass on Thursday, Sept. -

Catholic Charity in Perspective: the Social Life of Devotion in Portugal and Its Empire (1450-1700)

Catholic Charity in Perspective: The Social Life of Devotion in Portugal and its Empire (1450-1700) Isabel dos Guimarães Sá Universidade do Minho [email protected] Abstract This article tries to outline the major differences between practices of charity within Europe, either comparing Catholics to Protestants, or different Catholic areas. The point of departure is constituted by the study of the Misericórdias, lay confraternities under royal protection who would develop as one of the main (if not the greatest) dispensers of charity either in Portugal or its Empire. Its evolution since the formation of the first misericórdia in Lisbon to the end of the seventeenth century is analysed, relating these confraternities to political, social and religious changes that occurred in the period under analysis. Issues related to their functioning, membership, rules, and economic activities, as well as the types of needy they cared for, are also dealt with, mainly through the comparison of different colonial and metropolitan misericórdias. Keywords Charity; Catholic and Protestant Europe; Poverty; Devotion; State Building In the past, charity was a form of devotion, being one of the ways in which Christians could honor God. As one of the theological virtues, together with faith and hope, it enjoyed a high position in the hierarchy of religious behavior. The concern with charity was common to Catholics and Protestants, but with one major difference. Whilst the former could obtain salvation through good works and might be relatively sure that forgiveness of sins could be obtained through charity, the latter could not rely on such a possibility, since God alone could save believers, without the agency of the individual or intermediaries. -

Philadelphia Meeting, Synods Will Be Part of Debate on Families

The CatholicWitness The Newspaper of the Diocese of Harrisburg September 26, 2014 Vol. 48 No. 18 CHRIS HEISEY, THE CATHOLIC WITNESS The colors of Hispanic heritage filled St. Patrick Cathedral and the steps of the state Capitol in Harrisburg Sept. 14 for the Diocesan Hispanic Heritage Mass. The celebration displayed the culture and gifts of Hispanic Catholics, and marked the 70th anniversary of ministry to Spanish-speaking Catholics in the diocese. See cover- age of the Mass and the Hispanic Apostolate on pages 8 and 9. Philadelphia Meeting, Synods Will be Part of Debate on Families By Francis X. Rocca Pope Francis has said both synods will con- Catholic News Service sider, among other topics, the eligibility of divorced and civilly remarried Catholics to The World Meeting of Families in Phila- receive Communion, whose predicament he delphia in September 2015 will serve as a has said exemplifies a general need for mercy forum for debating issues on the agenda for in the church today. the world Synod of Bishops at the Vatican the “We’re bringing up all the issues that would following month, said the two archbishops re- have appeared in the preparation documents sponsible for planning the Philadelphia event. for the synod as part of our reflection,” said At a Sept. 16 briefing, Archbishop Vincen- Archbishop Charles J. Chaput of Philadel- zo Paglia, president of the Pontifical Council phia, regarding plans for the world meeting. for the Family, described the world meeting “I can’t imagine that any of the presenters as one of several related events to follow the won’t pay close attention to what’s happen- October 2014 extraordinary Synod of Bishops ing” in Rome.