Lumen Gentium's “Subsistit In” Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spiritual Responses to the Regulation of Birth (A Historical Comparison) Richard Fehring Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette College of Nursing Faculty Research and Nursing, College of Publications 1-1-2002 Spiritual Responses to the Regulation of Birth (A Historical Comparison) Richard Fehring Marquette University, [email protected] Elizabeth McGraw Published version. Life and Learning, Vol. XII (2002): 265-286. Publisher Link. © 2002 University Faculty for Life, Inc. Used with permission. Spiritual Responses to the Regulation of Birth (A Historical Comparison) Richard J. Fehring, D.N.Sc, R.N. Elizabeth McGraw, B.A., R.N. ABSTRACT Over 30 years ago the founders of the Christian Family Movement (CFM), a worldwide Catholic family action group, conducted a survey to investigate the marital effects of practicing “rhythm.” Their final report indicated that many participants felt that periodic abstinence was harmful to their marriage and caused spiritual and religious distress. The CFM survey results were thought to have been influential in convincing the 1966 Papal Birth Control Commission to recommend a change in church teaching. The purpose of this paper is to report a re-analysis of the 1966 archived data (in the light of the Papal Encyclical Humane Vitae–On the Regulation of Birth) and to compare that study with responses from married couples using modern methods of NFP, i.e., methods that purport to be more effective and to have fewer days of periodic abstinence. This paper will provide an examination of the original study within its historical context and report on the responses relating to spirituality from the 1966 couples in comparison with couples currently practicing periodic abstinence through the Billings Ovulation Method. -

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa was consecrated as the Roman Catholic Diocesan Bishop of Botucatu in Brazil on December !" #$%&" until certain views he expressed about the treatment of the Brazil’s poor, by both the civil (overnment and the Roman Catholic Church in Brazil caused his removal from the Diocese of Botucatu. His Excellency was subsequently named as punishment as *itular bishop of Maurensi by the late Pope Pius +, of the Roman Catholic Church in #$-.. His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord Carlos Duarte Costa had been a strong advocate in the #$-0s for the reform of the Roman Catholic Church" he challenged many of the 1ey issues such as • Divorce" • challenged mandatory celibacy for the clergy, and publicly stated his contempt re(arding. 2*his is not a theological point" but a disciplinary one 3 Even at this moment in time in an interview with 4ermany's Die 6eit magazine the current Bishop of Rome" Pope Francis is considering allowing married priests as was in the old time including lets not forget married bishops and we could quote many Bishops" Cardinals and Popes over the centurys prior to 8atican ,, who was married. • abuses of papal power, including the concept of Papal ,nfallibility, which the bishop considered a mis(uided and false dogma. His Excellency President 4et9lio Dornelles 8argas as1ed the Holy :ee of Rome for the removal of His Excellency Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa from the Diocese of Botucatu. *he 8atican could not do this directly. 1 | P a g e *herefore the Apostolic Nuncio to Brazil entered into an agreement with the :ecretary of the Diocese of Botucatu to obtain the resi(nation of His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord. -

The International Union of Social Studies of Malines and the Catholic Cultural Turn Drafting a Moral Code at the End of the Constantinian Era

Church History Church History and and Religious Culture 99 (2019) 504–523 Religious Culture brill.com/chrc The International Union of Social Studies of Malines and the Catholic Cultural Turn Drafting a Moral Code at the End of the Constantinian Era Dries Bosschaert KU Leuven [email protected] Abstract The present article argues that the unexpected end of the Union de Malines’ Code de morale culturelle, an international collaboration of prominent twentieth-century Catholic moral theologians, should be attributed to three shifts in Catholic Social Teaching, only the first two of which the Union de Malines managed to undergo: from scholastic hegemony to theological diversity, from social doctrine to personalism, and from a juridical style of writing to a humanistic one. Particularly this last shift, intro- duced by the Second Vatican Council, proved to be a too big a leap for the Union, understood as a ‘little social tradition,’ to take. The cultural turn, which the Union de Malines had in fact anticipated, proved by the end of the council to belong to the future. Keywords Union Internationale d’Etudes Sociales de Malines (Union de Malines) – Catholic Social Teaching – Theology of Culture – Gaudium et spes – Second Vatican Council In 1961, the French Dominican Marie-Dominique Chenu announced in his pro- grammatic La fin de l’ère Constantinienne the renewal of Western Christianity and its transformation into a global church, including the collapse of the clas- sical doctrinal tradition of social Catholicism.1 For a long time this tradition 1 Marie-Dominique Chenu, “La fin de l’ère Constantinienne,” in Un concile pour notre temps, ed. -

CURRENT THEOLOGY SOME RECENT DEVELOPMENTS in DOGMATIC THEOLOGY Life, They Tell Us, Was Simpler Fifty Years Ago

CURRENT THEOLOGY SOME RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN DOGMATIC THEOLOGY Life, they tell us, was simpler fifty years ago. We can at least hope this was true of the task of keeping abreast of developments in dogmatic theology. Today the most assiduous student is in danger of engulfment in the torrent of theological works that threatens to flood us all. While we must thank God for this extraordinary dynamism, we are none the less faced with a problem. How to cope with this growth? How indeed to discover the pub lished material? Language itself throws up one barrier. Theological litera ture, Catholic and otherwise, appears today in every tongue, including the Scandinavian.1 Catholic writers, largely deserting Latin, are thereby abandoning a ready-made international communications medium. And however valuable may be the rapports with the contemporary mind thus facilitated, only another Mezzofanti would find it easy to keep up with the published work of Catholic theologians. The "traditional reluctance of European publishers to sell their books after they have gone to the trouble of printing them," to which E. O'Brien, S.J., recently referred (THEOLOGICAL STUDIES 17 [1956] 39), does nothing to ease the burden of the English- speaking scholar. Slim budgets, small printings, and a deep-rooted failure to understand that "it pays to advertise" explain in part this vexing phe nomenon. But these we shall probably always have with us. Even as formidable a research student as Dr. Johannes Quasten has tasted of the frustration so discouraging to less hardy souls.2 Time and space permitting, 1 And the Flemish and the Irish. -

Prezbiter – Svećenik U Hrvatskoj Pokoncilskoj Teološkoj Literaturi (1965.-2010.)

SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU KATOLIČKI BOGOSLOVNI FAKULTET Danijel Crnić Prezbiter – svećenik u hrvatskoj pokoncilskoj teološkoj literaturi (1965.-2010.) Doktorski rad Mentor: prof. dr. sc. Josip Baloban Zagreb, 2013. Informacije o mentoru Josip Baloban rođen je 17. svibnja 1949. godine u Brebrovcu, župa Slavetić, Zagrebačka nadbiskupija. Osmogodišnju školu pohađao je u Slavetiću i Petrovini (1956.- 1964.). Klasičnu gimnaziju završio je na Interdijecezanskoj srednjoj školi za spremanje svećenika u Zagrebu 1968. godine. Studij dvije godine filozofije i jednu godinu teologije završio je na Katoličkom bogoslovnom fakultetu u Zagrebu (1968.-1971.). Studij teologije nastavio je na Ludwig-Maximilianovom sveučilištu u Münchenu, gdje je i diplomirao 1974. godine. 11. kolovoza 1974. godine zaređen je za svećenika Zagrebačke nadbiskupije. 1976. godine tadašnji zagrebački nadbiskup Franjo Kuharić šalje ga na poslijediplomski i doktorandski studij u München, gdje je i doktorirao 1981. godine. Naslov disertacije bio je „Kirche in einer sozialistischen Gesellschaft. Analyse der gegenwärtigen pastoralen Situation in der Erzdiözese Zagreb (Nordkroatien) unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der distanzierten Kirchlichkeit“. Disertacija je objavljena na njemačkom jeziku 1982. godine u nizu Studien zur Praktischen Theologie, Band 24. 1981. godine vraća se u Hrvatsku, te biva imenovan subsidijarom u župi sv. Luke Travno-Zagreb (1981.-1984.), zatim u župi sv. Mateja u Dugavama-Zagreb (1984.-1986.). Od 1981. do danas predaje na Katoličkom bogoslovnom fakultetu Sveučilišta u Zagrebu (odsada KBF-u), najprije 1981. na Katehetskom institutu, a zatim od 1982. kao asistent na filozofsko-teološkom šestogodišnjem studiju. U prvih dvadeset godina predaje predmete iz teologije i katehetike. Na istom Fakultetu se habilitirao 1990. godine s knjigom “Hrvatska kršćanska obitelj na pragu XXI. -

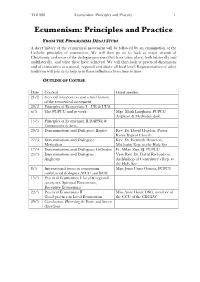

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

Advent & Christmas

2017 | 2018 PREPARING HEART & HOME Advent & Christmas PLANNER we wait in joyful hope Copyright © 2010 - 2017 Jennifer Mackintosh -Additional copies may be obtained at www.wildflowersandmarbles.com | Permission is granted to share personal copies, copy or adapt this forco individualpyrigh familyt 20 use,17 but, Jnoten forn imassfer distribution Macki nor tresaleosh without the author’s explicit permission. | Sharing on social media is encouraged as long as posts link directly to www.wildflowersandmarbles.com Advent - Consider First This book became a reality over a period of years - time which I spent joyfully uncovering the riches and traditions within the Catholic Church for my own family - traditions that prepare the heart for the great feast of Christmas. Without preparation, we may arrive at Christmas morning without first quietly considering and preparing for the gift of the Nativity. Advent is a season of quiet preparation in the home and the heart, and this atmosphere is cultivated carefully in our plans and activities. Consider first. As you consider the pages and ideas here (some are my own, most are compiled and gathered from other resources listed at the end of the book), and plan what you will bring into your own home as you set the atmosphere of preparation during Advent, please consider your family and your own time availability. One does not have to check off everything listed here to enjoy a beautiful and rich Advent! When we began celebrating the liturgical year as a family, I had a handful of holy cards, a liturgical year calendar, and a great desire to tap into the richness the Church offered through the rhythm of Her year. -

Branson-Shaffer-Vatican-II.Pdf

Vatican II: The Radical Shift to Ecumenism Branson Shaffer History Faculty advisor: Kimberly Little The Catholic Church is the world’s oldest, most continuous organization in the world. But it has not lasted so long without changing and adapting to the times. One of the greatest examples of the Catholic Church’s adaptation to the modernization of society is through the Second Vatican Council, held from 11 October 1962 to 8 December 1965. In this gathering of church leaders, the Catholic Church attempted to shift into a new paradigm while still remaining orthodox in faith. It sought to bring the Church, along with the faithful, fully into the twentieth century while looking forward into the twenty-first. Out of the two billion Christians in the world, nearly half of those are Catholic.1 But, Vatican II affected not only the Catholic Church, but Christianity as a whole through the principles of ecumenism and unity. There are many reasons the council was called, both in terms of internal, Catholic needs and also in aiming to promote ecumenism among non-Catholics. There was also an unprecedented event that occurred in the vein of ecumenical beginnings: the invitation of preeminent non-Catholic theologians and leaders to observe the council proceedings. This event, giving outsiders an inside look at 1 World Religions (2005). The Association of Religious Data Archives, accessed 13 April 2014, http://www.thearda.com/QuickLists/QuickList_125.asp. CLA Journal 2 (2014) pp. 62-83 Vatican II 63 _____________________________________________________________ the Catholic Church’s way of meeting modern needs, allowed for more of a reaction from non-Catholics. -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC JOURNEY OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI TO BRAZIL ON THE OCCASION OF THE FIFTH GENERAL CONFERENCE OF THE BISHOPS OF LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN MEETING AND CELEBRATION OF VESPERS WITH THE BISHOPS OF BRAZIL ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI Catedral da Sé, São Paulo Friday, 11 May 2007 Dear Brother Bishops! "Although he was the Son of God, he learned obedience through what he suffered; and being made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation to all who obey him." (cf. Heb 5:8-9). 1. The text we have just heard in the Lesson for Vespers contains a profound teaching. Once again we realize that God’s word is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword; it penetrates to the depths of the soul and it grants solace and inspiration to his faithful servants (cf. Heb 4:12). I thank God for the opportunity to be with this distinguished Episcopate, which presides over one of the largest Catholic populations in the world. I greet you with a sense of deep communion and sincere affection, well aware of your devotion to the communities entrusted to your care. The warm reception given to me by the Rector of the Catedral da Sé and by all present has made me feel at home in this great common House which is our Holy Mother, the Catholic Church. 2 I extend a special greeting to the new Officers of the National Conference of Brazilian Bishops and, with gratitude for the kind words of its President, Archbishop Geraldo Lyrio Rocha, I offer prayerful good wishes for his work in deepening communion among the Bishops and in promoting common pastoral activity in a territory of continental dimensions. -

The Catholic Faith and “Once-Upon-A-Time Catholics” Deacon James H

The Catholic Faith and “Once-Upon-a-Time Catholics” Deacon James H. Toner Our Lady of Grace Catholic Church 22 September 2011 I. Why does it matter if someone leaves [and goes elsewhere or becomes lax]? A. “Many elements of sanctification and of truth are found outside [the Church]” B. The Catholic Church “is the sole Church of Christ” (Lumen Gentium #8; CCC #819, 816). C. “If it is true that the followers of other religions can receive divine grace, it is also certain that objectively speaking they are in a gravely deficient situation in comparison with those who, in the Church, have the fullness of the means of salvation” (Dominus Iesus [6 Aug 2000] #22). D. Those who publicly reject the Lord will be rejected (Mt 10:33; cf 2 Tm 2:12). 1. “They could not be saved who, knowing that the Catholic Church was founded as necessary by God through Christ, would refuse either to enter it, or to remain in it” (LG #14). (Cf. “invincible ignorance”) 2. “Those who, through no fault of their own, do not know the Gospel of Christ or his Church, but who nevertheless seek God with a sincere heart . may achieve eternal salvation” (LG #16). (Cf. “baptism of desire”). II. Four nouns (see CCC #2089) about swerving from the truth (2 Tim 2:18): A. Apostasy: total repudiation of the Christian faith (CCC #2089). B. Heresy: obstinate denial (while professing Christianity), after Baptism, of a truth which must be believed with divine and Catholic faith; denial of orthodoxy. 1. Material heretic: does not recognize Church authority and thus denies it. -

Ecclesiastical Materialism

ECCLESIASTICAL MATERIALISM by Most Reverend Donald J. Sanborn Introduction. From the title, one might expect Roman Catholic Church condemns as a mortal sin of that I would be writing about avarice among the sacrilege the giving the Holy Eucharist to non- clergy. I am not addressing that at all, however. Catholics. The Novus Ordo approves of it. (1983 Code Recently I received from an old friend, who is a of Canon Law) The Roman Catholic Church Novus Ordo conservative, a note in which he invited condemns the use of birth control devices as mortally me to come back “to Rome — and the true Church — sinful and intrinsically evil. The Novus Ordo permits outside of which there is no salvation.” birth control devices for prostitutes. (Ratzinger, His invitation, although made with all good “Benedict XVI,” in a published interview) intentions, nevertheless prompted me to write this What I have responded above is only a smattering response. What he means is that I should give up my of the myriad dogmatic, moral, liturgical, and repudiation of Vatican II and its subsequent reforms, disciplinary contradictions between the Roman submit to the local bishop, and be somehow Catholic Church and what we call the Novus Ordo. “regularized” within the structures of the Novus We could provide the endless list of heresies and Ordo. blasphemies of Bergoglio. But these things are well known. First response. My first response is the following. The Roman Catholic Church teaches that The four marks of the Church. I will add to there is one true Church of Christ, and only one, this first response the four marks of the Church. -

New Directions for Catholic Theology. Bernard Lonergan's Move Beyond

JHMTh/ZNThG; 2019 26(1): 108–131 Benjamin Dahlke New Directions for Catholic Theology. Bernard Lonergan’s Move beyond Neo-Scholasticism DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/znth-2019-0005 Abstract: Wie andere aufgeschlossene Fachvertreter seiner Generation hat der kanadische Jesuit Bernard Lonergan (1904–1984) dazu beigetragen, die katho- lische Theologie umfassend zu erneuern. Angesichts der oenkundigen Gren- zen der Neuscholastik, die sich im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts als das Modell durchgesetzt hatte, suchte er schon früh nach einer Alternative. Bei aller Skep- sis gegenüber dem herrschenden Thomismus schätzte er Thomas von Aquin in hohem Maß. Das betraf insbesondere dessen Bemühen, die damals aktuellen wissenschaftlichen und methodischen Erkenntnisse einzubeziehen. Lonergan wollte dies ebenso tun. Es ging ihm darum, der katholischen Theologie eine neue Richtung zu geben, also von der Neuscholastik abzurücken. Denn diese berücksichtigte weder das erkennende Subjekt noch das zu erkennende Objekt hinreichend. Keywords: Bernard Lonergan, Jesuits, Neo-Scholasticism, Vatican II, Thomism Bernard Lonergan (1904–1984), Canadian-born Jesuit, helped to foster the re- newal of theology as it took place in the wake of Vatican II, as well in the council’s aftermath. He was aware of the profound changes the discipline was going through. Since the customary way of presenting the Christian faith – usu- ally identified with Neo-Scholasticism – could no longer be considered adequate, Lonergan had been working out an alternative approach. It was his intent to provide theology with new foundations that led him to incorporate contem- porary methods of science and scholarship into theological practice. Faith, as he thought, should be made intelligible to the times.1 Thus, Lonergan moved beyond the borders set up by Neo-Scholasticism.