Léo Volker Architect of Aggiornamento

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catholics and Jews: and for the Sentiments Expressed

Archdiocesan News A PUBLICATION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH OF CAPE TOWN • ISSUE NO 81 • JULY-SEPTEMBER 2016 • FREE OF CHARGE WORLD YOUTH DAY 2016 At the end of July an Archdiocesan contingent of seven young people (and Fr Charles) headed to Poland to be a part of World Youth Day 2016. They spent some days in Czestochowa Diocese in the small town of Radonsko, experiencing Polish hospitality and visiting the shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa. Then they headed off to Krakow for various activities and an encounter with millions of other pilgrims from all over the world, culminating in an all-night vigil and Mass with Pope Francis. Claremont Mosque condemns killing of Catholic Priest PRESS STATEMENT – 26 JULY 2016 CMRM Condemns Inhumane Killing of Catholic Priest The Claremont Main Road Mosque (CMRM) congregation strongly con- demns the brutal killing of an 85 year-old Catholic priest by two ISIS/Da`ish supporters during a Mass at a Church in Normandy, France. The inhumane and gruesome killing of the elderly Father Jacques Hamel and the sacrili- geous violation of a sacred prayer space bears testimony to the merciless ideology of Da`ish. It is apparent that Da`ish is hell-bent on fuelling a reli- gious war between Muslims and Christians. However, their war is a war on humanity and our response should reflect a deep respect for the sanctity of all human life. This tragic incident should spur us to redouble our efforts at reaching out to each other across religious divides. Our thoughts and prayers are with the congregation of the Church in Saint-Etienne-du-Rouvray and the Catholic Church at large. -

MZ 2-2016 Afrika V7 Final.Indd

ISSN 0259-7446 EUR 6,50 medienmedien Kommunikation in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart && zeitzeit Thema: Afrikanisch-Europäische Medienbeziehungen Imperiale Kommunikationsarbeit Von Lumumba bis Ebola Dekolonisierung des Blicks International News Reporting in the Multidimensional Network Against the Hypothesis of a China-EU Collaboration in Africa Research Corner: Eine Zeitung für Tibet 22/2016/2016 Jahrgang 31 m&z 2/2016 medien & zeit Impressum MEDIENINHABER, HERAUSGEBER UND VERLEGER Verein „Arbeitskreis für historische Kommunikationsforschung (AHK)“, Währinger Straße 29, 1090 Wien, Inhalt ZVR-Zahl 963010743 http://www.medienundzeit.at © Die Rechte für die Beiträge in diesem Heft liegen beim „Arbeitskreis für historische Kommunikationsforschung (AHK)“ HERAUSGEBERINNEN Barbara Metzler, Erik Bauer, Christina Krakovsky REDAKTION BUCHBESPRECHUNGEN Gaby Falböck, Roland Steiner, Thomas Ballhausen Imperiale Kommunikationsarbeit REDAKTION RESEARCH CORNER Zur medialen Rahmung von Mission im 19. Erik Bauer, Christina Krakovsky, Barbara Metzler, LEKTORAT & LAYOUT und 20. Jahrhundert Diotima Bertel, Julia Himmelsbach, Barbara Metzler, Judith Rosenkranz; Richard Hölzl 3 Diotima Bertel PREPRESS Grafikbüro Ebner, Wiengasse 6, 1140 Wien, Von Lumumba bis Ebola VERSAND ÖHTB – Österreichisches Hilfswerk für Taubblinde und Standarderzählungen in der österreichischen hochgradig Hör- und Sehbehinderte Afrika-Berichterstattung (1960-2015) Werkstätte Humboldtplatz 7, 1100 Wien, ERSCHEINUNGSWEISE & BEZUGSBEDINGUNGEN Martin Sturmer 18 medien & zeit erscheint vierteljährlich -

Community of Kinsasha

Hospitallers Africa AFRICA, KEEP THE LAMP CHAF — FLYER N°7 NOVEMBER 2016 OF HOSPITALITY ALIGHT The Democratic Republic of Congo help them to recover health and return to their “Zaire”, Central Africa, 9 border coun- family". tries. In 1960 he obtained the independ- The Team of CSM earlier is concerned of the ence. The capital Kinshasa 11 million of mental health approach devices for the popula- inhabitants. The DRC has more than 450 tion, especially beacause of the lack of re- ethnic groups with large cultural diversi- sources. Thus appear "antennas": consultation ties. Christianity is the religion more in various districts of the city center. important. Since his arrival to Kinshasa the sisters mobilized their local capabilities in favor of the The presence of the Congregation: mission hospital. Now we can say that the in the heart of mental health . germ of what is now the hospital family is at Called by Cardinal Joseph Malula, the the origin of the Congregation in Kinshasa. Congregation is established in Kinshasa A small group of "mothers" actively collaborat- in September 30, 1989 with the arrival ing in the psychiatric hospital in Kinkole. On of the three first sisters to Kinshasa: April 24, 2005, it was the chosen date to install Ángela, Ma. Covadonga and Andrea; in the "body" to this group which began to grow and, above all, began to arise among them a order to take care of the mentally sick, great desire to live the hospitaller values taking part of the health structure of the and engage actively in the field of mission. -

Inculturation and Catholicity in Relation to the Worldwide Church

INCULTURATION AND CATHOLICITY IN RELATION TO THE WORLDWIDE CHURCH Look up at the sky and count the stars. —Gen. 15:5 Let us begin where our issue arose first. Let us start with a story, or better with an image. The image of a couple standing at the beginning of the process that led us to the possibility and the need to organize a conference on inculturation and catholicity I would like to begin with the father of all believers, Abraham. Abraham could not have been alone in his experience. A man cannot be a father on his own. Abra- ham would have been nowhere without Sarah. The promise given to him was not given to him, but to him and her. It was a promise of life. A man alone does not manage that. In fact the author of the letter to the Hebrews (11:11) enables Sarah, too, to become the progenitor of the child, in a text which according to some ex- egetes is "a cross which is frankly too heavy for expositors to bear."1 And in the Genesis text we read, "Yahweh dealt kindly with Sarah, as Yahweh had said, and did what Yahweh had promised her."2 In the end you begin to wonder who really was the father of Isaac. Sarah and Abram are not only the parents of all believers. They are the ances- tors of all unbelievers.3 God told them to leave their country, their kindred, their culture, their all, in view of a new life. An initiative by which all human clans would be blessed. -

Branson-Shaffer-Vatican-II.Pdf

Vatican II: The Radical Shift to Ecumenism Branson Shaffer History Faculty advisor: Kimberly Little The Catholic Church is the world’s oldest, most continuous organization in the world. But it has not lasted so long without changing and adapting to the times. One of the greatest examples of the Catholic Church’s adaptation to the modernization of society is through the Second Vatican Council, held from 11 October 1962 to 8 December 1965. In this gathering of church leaders, the Catholic Church attempted to shift into a new paradigm while still remaining orthodox in faith. It sought to bring the Church, along with the faithful, fully into the twentieth century while looking forward into the twenty-first. Out of the two billion Christians in the world, nearly half of those are Catholic.1 But, Vatican II affected not only the Catholic Church, but Christianity as a whole through the principles of ecumenism and unity. There are many reasons the council was called, both in terms of internal, Catholic needs and also in aiming to promote ecumenism among non-Catholics. There was also an unprecedented event that occurred in the vein of ecumenical beginnings: the invitation of preeminent non-Catholic theologians and leaders to observe the council proceedings. This event, giving outsiders an inside look at 1 World Religions (2005). The Association of Religious Data Archives, accessed 13 April 2014, http://www.thearda.com/QuickLists/QuickList_125.asp. CLA Journal 2 (2014) pp. 62-83 Vatican II 63 _____________________________________________________________ the Catholic Church’s way of meeting modern needs, allowed for more of a reaction from non-Catholics. -

HUMAN DIGNITY Discourses on Universality and Inalienability

HUMAN DIGNITY Discourses on Universality and Inalienability One World Theology (Volume 8) HUMAN DIGNITY Discourses on Universality and Inalienability 8 Edited by Klaus Krämer and Klaus Vellguth CLARETIAN COMMUNICATIONS FOUNDATION, INC. HUMAN DIGNITY Discourses on Universality and Inalienability Contents (One World Theology, Volume 8) Copyright © 2017 by Verlag Herder GmbH, Freiburg im Breisgau Published by Claretian Communications Foundation, Inc. U.P. P.O. Box 4, Diliman 1101 Quezon City, Philippines Preface ......................................................................................... ix Tel.: (02) 921-3984 • Fax: (02) 921-6205 [email protected] www.claretianpublications.ph Anthropological Remarks on Human Dignity Claretian Communications Foundation, Inc. (CCFI) is a pastoral endeavor of the Human Dignity in the Light of Anthropology ....................... 3 Claretian Missionaries in the Philippines that brings the Word of God to people from all and the History of Ideas walks of life. It aims to promote integral evangelization and renewed spirituality that is geared towards empowerment and total liberation in response to the needs and challenges Josef Schuster of the Church today. Reaffirming the Theology of Human Dignity in Africa .......... 17 CCFI is a member of Claret Publishing Group, a consortium of the publishing houses of the Claretian Missionaries all over the world: Bangalore, Barcelona, Buenos Aires, Chennai, Critical challenges and salient hopes in Tanzania Colombo, Dar es Salaam, Lagos, Macau, Madrid, Manila, Owerry, São Paolo, Varsaw and Aidan G. Msafiri Yaoundè. Anthropological Annotations on Human Dignity from an Asian Perspective ............................................................... 27 Francis-Vincent Anthony Discussion Forum as the Survival Strategy ........................ 37 of a Kaqchikel Community in Guatemala Andreas Koechert Roots of Human Dignity in the Specific Context An Historical Perspective on Violations of Dignity ............. -

The Society for the Propagation of the Faith National Director’S Message

VOL 68, NO. 3 MAY/JUNE 2010 Matteo Ricci Model for Dialogue The Church in Russia The Augustinians in Japan Zimbabwe Mother of Peace Orphanage Focus on Burkina Faso The Society for the Propagation of the Faith National Director’s Message Happy spring! As we celebrate Troy worked tirelessly connecting children in Edmonton to mis- the season of new life, we also sion children throughout the world. He told and lived the mis- introduce to you a “new look” sion story. We were blessed to have him as part of our mission for our magazine, Missions To- family. Please keep him and his community, the Spiritans, in day. In response to a number of your prayers. our readers’ concerns about the size of the print, coloured back- Earlier I referenced the challenges found in mission work profiled grounds and spacing that made in this edition of the magazine. We have also experienced the the magazine difficult for them challenges of this work albeit in a different way here at home. In to read, we are introducing a fo- the past year we have, in one way or another, experienced eco- lio size magazine with new de- nomic challenges. Thank you to each of you for your faithful sign and layout features we hope address these concerns. Please support and prayers during these times. They sustain us and pro- feel free to share your thoughts about these changes with us. vide us with renewed hope. The last few issues of Missions Today have featured the minority May you enjoy a safe and relaxing summer. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/27/2021 12:30:54PM Via Free Access

Book Reviews 541 Léon de Saint Moulin, S.J. Histoire des jésuites en Afrique: Du XVIe siècle à nos jours. Paris: Éditions jésuites, 2016. Pp. 137. Pb, €12. The presence of the Jesuits in Africa is as old as the Society of Jesus itself. Un- fortunately, their history on the continent is also the least studied. This volume is short, yet it is the first comprehensive history of the Jesuits in Africa. In its 137 pages, the author, himself a seasoned missionary, seeks to focus not on mission history as such, but on the birth of local churches. The book is divided in three parts corresponding to three periods of the history of the Jesuits in Africa. The Portuguese or Padroado era covers the early missions in the kingdom of Congo and Angola, Ethiopia, Cape Verde, the Zambesi, and Madagascar, from the foundation of the Society of Jesus in 1540 to its suppression in 1773. Beyond a clear chronological report of events, nothing substantial is said about this pe- riod. Then follows the colonial era, from the restoration of the Society in 1814 to the wave of African nations becoming independent in the 1960s. Characteristic of this period was the emergence of most of the present Jesuit provinces and sub-provinces in Africa. Here, de Saint Moulin provides a chronology of those foundations, their most important achievements, and the most significant mis- sionaries (including Africans) in Madagascar, the Zambesi, and Central, West- ern, and Eastern Africa. Missions were dependent upon colonial powers for their foundation and functioning. Yet, missionaries also took a stand against colonial abuses. -

New Directions for Catholic Theology. Bernard Lonergan's Move Beyond

JHMTh/ZNThG; 2019 26(1): 108–131 Benjamin Dahlke New Directions for Catholic Theology. Bernard Lonergan’s Move beyond Neo-Scholasticism DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/znth-2019-0005 Abstract: Wie andere aufgeschlossene Fachvertreter seiner Generation hat der kanadische Jesuit Bernard Lonergan (1904–1984) dazu beigetragen, die katho- lische Theologie umfassend zu erneuern. Angesichts der oenkundigen Gren- zen der Neuscholastik, die sich im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts als das Modell durchgesetzt hatte, suchte er schon früh nach einer Alternative. Bei aller Skep- sis gegenüber dem herrschenden Thomismus schätzte er Thomas von Aquin in hohem Maß. Das betraf insbesondere dessen Bemühen, die damals aktuellen wissenschaftlichen und methodischen Erkenntnisse einzubeziehen. Lonergan wollte dies ebenso tun. Es ging ihm darum, der katholischen Theologie eine neue Richtung zu geben, also von der Neuscholastik abzurücken. Denn diese berücksichtigte weder das erkennende Subjekt noch das zu erkennende Objekt hinreichend. Keywords: Bernard Lonergan, Jesuits, Neo-Scholasticism, Vatican II, Thomism Bernard Lonergan (1904–1984), Canadian-born Jesuit, helped to foster the re- newal of theology as it took place in the wake of Vatican II, as well in the council’s aftermath. He was aware of the profound changes the discipline was going through. Since the customary way of presenting the Christian faith – usu- ally identified with Neo-Scholasticism – could no longer be considered adequate, Lonergan had been working out an alternative approach. It was his intent to provide theology with new foundations that led him to incorporate contem- porary methods of science and scholarship into theological practice. Faith, as he thought, should be made intelligible to the times.1 Thus, Lonergan moved beyond the borders set up by Neo-Scholasticism. -

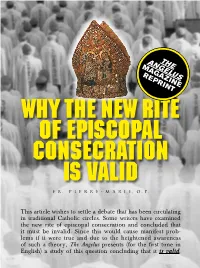

Why the New Rite of Episcopal Consecration Is Valid Fr

ANGELUSTHE MAGAZINE REPRINT WHY THE NEW RITE OF EPISCOPAL CONSECRATION IS VALID Fr. Pierre-Marie, O.P. This article wishes to settle a debate that has been circulating in traditional Catholic circles. Some writers have examined the new rite of episcopal consecration and concluded that it must be invalid. Since this would cause manifest prob- lems if it were true and due to the heightened awareness of such a theory, The Angelus presents (for the first time in English) a study of this question concluding that it is valid. 2 This article was translated exclusively by Angelus Press from Sel de la Terre (No.54., Autumn 2005, pp.72-129). Fr. Pierre-Marie, O.P., is a member of the traditional Dominican monastery at Avrillé, France, several of whose members were ordained by Archbishop Lefebvre and which continues to receive its priestly ordinations from the bishops serving the Society of Saint Pius X which Archbishop Lefebvre founded. He is a regular contributor to their quarterly review, Sel de la Terre (Salt of the Earth). The English translations contained in the various tables were prepared with the assistance of H.E. Bishop Richard Williamson, Dr. Andrew Senior (professor at St. Mary’s College, St. Mary’s, Kansas), and Fr. Scott Gardner, SSPX. ollowing the Council, in 1968 a new rite for Orders or is merely “a sacramental,” an ecclesiastical the ordination of bishops was promulgated. ceremony wherein the powers of the episcopate, It was, in fact, the first sacrament to undergo its “bound” in the simple priest, are “freed” for the “aggiornamento,” or updating. -

Archbishop's Stewardship Challenge Making Stewardship a Way of Life in the Year of Faith

Archdiocesan News A PUBLICATION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH OF CAPE TOWN • ISSUE NO 67 • OCTOBER-DECEMBER 2012 • FREE OF CHARGE Archbishop's Stewardship Challenge Making stewardship a way of life in the Year of Faith A Christian Steward is a Christ follower who: • Receives God’s gifts gratefully • Cherishes and tends them in a responsible way • Shares them in justice and love for all • Returns them with interest to the Lord (USCCB Stewardship: A Disciple’s Response) This means that we acknowledge that all we have has been given to us as a gift from God and we are grateful for all our gifts, our posses- sions, our health, our children, etc. We cherish these gifts and realise that we are accountable for all that we have been given, and we prom- ise to take care of them in a responsible way. For the benefit of others, God has given us all these gifts that we might be generous and give back a portion for the common good and in recognition of the bless- ings received from God (Malachi 3:10). We are also to use the gifts we have been given, and not to ‘bury’ them. Remember the Parable of the Talents. (Matthew 25:13-30) In a very practical way we are asked to give back to God from all Archbishop Brislin leads the way in the stewardship challenge, taking time out of his busy schedule to serve the poor that He has given to us in three ways: Time Talents Treasure THE STEWARDSHIP CHALLENGE TIME: spend one extra hour in prayer each week, go to an extra How do we do this? We spend more time in prayer with our Creator. -

Contested Moral Issues in Contemporary African Catholicism

Journal of Global Catholicism Volume 1 Article 4 Issue 2 African Catholicism: Contemporary Issues July 2017 Contested Moral Issues in Contemporary African Catholicism: Theological Proposals for a Hermeneutics of Multiplicity and Inclusion Stan Chu Ilo DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc Part of the African Studies Commons, Anthropological Linguistics and Sociolinguistics Commons, Catholic Studies Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Cultural History Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Folklore Commons, History of Christianity Commons, History of Religion Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Practical Theology Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, Social History Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Chu Ilo, Stan (2017) "Contested Moral Issues in Contemporary African Catholicism: Theological Proposals for a Hermeneutics of Multiplicity and Inclusion," Journal of Global Catholicism: Vol. 1: Iss. 2, Article 4. p.50-73. DOI: 10.32436/2475-6423.1015 Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc/vol1/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Catholicism by an authorized editor of CrossWorks. 50 STAN CHU ILO Contested Moral Issues in Contemporary African Catholicism: Theological Proposals for a Hermeneutics of Multiplicity and Inclusion Stan Chu Ilo has two doctoral degrees, one in theology and another in sociology of education.