Recent Roman Catholic Theology with Special Reference to Vatican II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of Sacrosanctum Concilium Part 2 Or, How to Grok

The development of Sacrosanctum Concilium Part 2 - a presentation by Seán O’Seasnáin on becoming familiar with Vatican II and the Liturgy with a focus on Chapter 4 of What Happened at Vatican II by John W. O’Malley The Lines Are Drawn - The First Period (1962) or, How to grok Sacrosanctum Concilium (SC) while avoiding moonbats and wingnuts from the vantage point of a young Irish friar in formation at the time of Vatican II The four aggiornamento modernization principles identified by John W. O’Malley p140f 1) ressourcement 2) adaptation 3) episcopal collegiality and 4) active participation (Ch.4 of What Happened at Vatican II) are correctly described by O’Malley as fundamental and traditional principles. In a harsh and pedantic review of What Happened at Vatican II the late Richard John Neuhaus, on one hand gives O’Malley back-handed compliments for his balanced analysis, and in the next sentence rushes in to castigate him with misleading accusations of presenting the ‘discontinuity’ perspective of the council. Neuhaus writes dismissively: “What Happened at Vatican II is a 372-page brief for the party of novelty and discontinuity. Its author comes very close to saying explicitly what is frequently implied: that the innovationists practiced subterfuge, and they got away with it” [10]. I would have to credit Neuhaus with providing a reminder here of how appropriate the ‘moonbat’ and ‘wingnut’ designations are when it comes to critiques of Vatican II and the liturgy. He writes: “In the decades following the council, many liberals made no secret of their belief that aggiornamento was a mandate for radical change, even revolution. -

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa was consecrated as the Roman Catholic Diocesan Bishop of Botucatu in Brazil on December !" #$%&" until certain views he expressed about the treatment of the Brazil’s poor, by both the civil (overnment and the Roman Catholic Church in Brazil caused his removal from the Diocese of Botucatu. His Excellency was subsequently named as punishment as *itular bishop of Maurensi by the late Pope Pius +, of the Roman Catholic Church in #$-.. His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord Carlos Duarte Costa had been a strong advocate in the #$-0s for the reform of the Roman Catholic Church" he challenged many of the 1ey issues such as • Divorce" • challenged mandatory celibacy for the clergy, and publicly stated his contempt re(arding. 2*his is not a theological point" but a disciplinary one 3 Even at this moment in time in an interview with 4ermany's Die 6eit magazine the current Bishop of Rome" Pope Francis is considering allowing married priests as was in the old time including lets not forget married bishops and we could quote many Bishops" Cardinals and Popes over the centurys prior to 8atican ,, who was married. • abuses of papal power, including the concept of Papal ,nfallibility, which the bishop considered a mis(uided and false dogma. His Excellency President 4et9lio Dornelles 8argas as1ed the Holy :ee of Rome for the removal of His Excellency Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa from the Diocese of Botucatu. *he 8atican could not do this directly. 1 | P a g e *herefore the Apostolic Nuncio to Brazil entered into an agreement with the :ecretary of the Diocese of Botucatu to obtain the resi(nation of His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord. -

The Vatican II Decree on the Eastern Catholic

KL BH The Vatican II Decree EH CH on the Eastern Catholic Churches Orientalium ecclesiarum - Fifty Years Later Carr Hall (Father Madden Hall) Trinity College (Trinity College Chapel) J.M. KellyJ.M. Library (coffee lounge) — — October 17 & 18, 2014 — KL CH TC N University of St. Michael’s College in the University of Toronto ORGANIZED BY THE METROPOLITAN ANDREY SHEPTYTSKY INSTITUTE OF EASTERN CHRISTIAN STUDIES www.sheptytskyinstitute.ca TC Co-sponsored by The Catholic Near East Welfare Association Centre for Research on the Second Vatican Council in Canada, St. Michael’s College Toronto Research on Vatican II and 21st Century Catholicism, Saint Paul University, Ottawa Brennan Hall ( Senior RoomCommon & Canada Room) Elmsley Hall (Charbonnel Lounge) — — CONFERENCE MAP CONFERENCE BH EH ANNOUNCEMENTS Saturday, October 18 9:00am—Father Madden Hall in Carr Hall, 100 St Joseph St. During the conference, snacks can be purchased across the street from Carr Hall at the coffee Morning Prayer according to the Byzantine Christian Tradition lounge in the Kelly Library. 9:30am—Father Madden Hall in Carr Hall, 100 St Joseph St. Lunch (available 11:30am-2:30pm) and dinner (available 5:30-7:30pm) can be purchased in 3) Bishop Nicholas Samra: “Eastern Catholicism in the Middle East Fifty Years after the Canada Room of Brennan Hall. Orientalium ecclesiarum” 11:00-11:45am Parallel sessions Bishop David Motiuk: “An Overview of the Ukrainian Catholic Church on the Eve of the Second Vatican Council”—Father Madden Hall in Carr Hall, 100 St Joseph St. Friday, October 17 Andriy Chirovsky: “TBA”—Charbonnel Lounge 1:00pm—Father Madden Hall in Carr Hall, 100 St Joseph St. -

Nemes György: Az Egyháztörténet Vázlatos Áttekintése

PPEK 97 Nemes György: Az egyháztörténet vázlatos áttekintése Nemes György Az egyháztörténet vázlatos áttekintése mű a Pázmány Péter Elektronikus Könyvtár (PPEK) – a magyarnyelvű keresztény irodalom tárháza – állományában. Bővebb felvilágosításért és a könyvtárral kapcsolatos legfrissebb hírekért látogassa meg a http://www.ppek.hu internetes címet. 2 PPEK / Nemes György: Az egyháztörténet vázlatos áttekintése Impresszum Nemes György Az egyháztörténet vázlatos áttekintése Jegyzet az Egri Hittudományi Főiskola Váci Levelező Tagozatának hallgatói számára A Piarista Tartományfőnökség 320/1999. sz. engedélyével. Munkatársak: Mészáros Gábor, Nagy Attila, Nemes Rita Lektorálta: Bocsa József A Középkor című fejezet egyik része (Mohamed és az iszlám) és A magyar egyház története című fejezet három része (A kezdetektől az Árpád-kor végéig; A reformáció és a katolikus megújulás; Kitekintés) Mészáros Gábor munkája. ____________________ A könyv elektronikus változata Ez a publikáció az Egri Hittudományi Főiskola Tanárképző Szakának Váci Levelező Tagozata által megjelentetett azonos című könyv szöveghű, elektronikus változata. Az elektronikus kiadás engedélyét a szerző, Nemes György Sch.P. adta meg. Ezt az elektronikus változatot a Pázmány Péter Elektronikus Könyvtár elvei szerint korlátlanul lehet lelkipásztori célokra használni. Minden más jog a szerzőé. PPEK / Nemes György: Az egyháztörténet vázlatos áttekintése 3 Tartalomjegyzék Impresszum ............................................................................................................................... -

Downside Abbey Press Release

DOWNSIDE ABBEY PRESS RELEASE Tuesday 3rd May 2016 IMMEDIATE RELEASE MINISTRY OF THE PRINTED WORD Scholar-Priests of the Twentieth Century Downside Abbey Press releases a collection of essays exploring the work of eleven priests whose ministry was that of the printed word. Pope St John Paul II reminded all priests of the need for on-going formation, both pastoral and intellectual; his belief was that pastoral activity needed grounding in assiduous study. With an output that spanned the 19th and 20th centuries, the work of the ‘Scholar Priests’ is considered relevant to the Church today. The book explores the work of both religious and secular priests, whose studies ranged across fields as diverse as biblical studies, liturgy, philosophy, history, theology and spirituality, including: Cardinal Gasquet OSB, George Tyrell SJ, Bernard Ward, Adrian Fortescue, John Hungerford Pollen SJ, Herbert Thurston SJ, Ronald Knox, Philip Hughes, David Knowles OSB, Christopher Butler OSB, and Frederick Copleston SJ. “There [is] here indeed a very wide diversity among these scholar priests in the variety of their formation, temperament, career, academic interests and, perhaps more interestingly, in their relations with the Church." Abbot Geoffrey Scott. Edited by Fr John Broadley and Fr Peter Phillips, the book includes contributions by Oliver Rafferty, Stewart Foster, Nicholas Paxton, Thomas McCoog, Dom Aidan Bellenger, Nicholas Schofield, Terry Tastard, Simon Johnson, and Michael Walsh. The book will be released on Thursday 19th May and is available for purchase at www.downside.co.uk priced at £35.00. ----------------PRESS RELEASE ENDS---------------- NOTES TO EDITORS Press contact Claire Wass: [email protected] / 01761 235151 Downside Abbey is a Roman Catholic monastery, and is home to a community of Benedictine monks. -

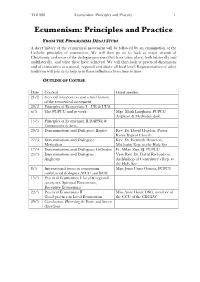

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

How Do the Writings of Pope Benedict XVI on "Transformation" Apply to a Couple's Growth in Holiness in Sacramental Marriage?

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2018 How do the writings of Pope Benedict XVI on "transformation" apply to a couple's growth in holiness in sacramental marriage? Houda Jilwan The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Jilwan, H. (2018). How do the writings of Pope Benedict XVI on "transformation" apply to a couple's growth in holiness in sacramental marriage? (Master of Philosophy (School of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/194 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW DO THE WRITINGS OF POPE BENEDICT XVI ON “TRANSFORMATION” APPLY TO A COUPLE’S GROWTH IN HOLINESS IN SACRAMENTAL MARRIAGE? Houda Jilwan A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy School of Philosophy and Theology The University of Notre Dame Australia 2018 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 1: The universal call to holiness .................................................................................. 11 1.1 Meaning of holiness ..................................................................................................... 11 1.2 A quick overview of the universal call to holiness in Scripture and Tradition .................. -

Branson-Shaffer-Vatican-II.Pdf

Vatican II: The Radical Shift to Ecumenism Branson Shaffer History Faculty advisor: Kimberly Little The Catholic Church is the world’s oldest, most continuous organization in the world. But it has not lasted so long without changing and adapting to the times. One of the greatest examples of the Catholic Church’s adaptation to the modernization of society is through the Second Vatican Council, held from 11 October 1962 to 8 December 1965. In this gathering of church leaders, the Catholic Church attempted to shift into a new paradigm while still remaining orthodox in faith. It sought to bring the Church, along with the faithful, fully into the twentieth century while looking forward into the twenty-first. Out of the two billion Christians in the world, nearly half of those are Catholic.1 But, Vatican II affected not only the Catholic Church, but Christianity as a whole through the principles of ecumenism and unity. There are many reasons the council was called, both in terms of internal, Catholic needs and also in aiming to promote ecumenism among non-Catholics. There was also an unprecedented event that occurred in the vein of ecumenical beginnings: the invitation of preeminent non-Catholic theologians and leaders to observe the council proceedings. This event, giving outsiders an inside look at 1 World Religions (2005). The Association of Religious Data Archives, accessed 13 April 2014, http://www.thearda.com/QuickLists/QuickList_125.asp. CLA Journal 2 (2014) pp. 62-83 Vatican II 63 _____________________________________________________________ the Catholic Church’s way of meeting modern needs, allowed for more of a reaction from non-Catholics. -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC JOURNEY OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI TO BRAZIL ON THE OCCASION OF THE FIFTH GENERAL CONFERENCE OF THE BISHOPS OF LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN MEETING AND CELEBRATION OF VESPERS WITH THE BISHOPS OF BRAZIL ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI Catedral da Sé, São Paulo Friday, 11 May 2007 Dear Brother Bishops! "Although he was the Son of God, he learned obedience through what he suffered; and being made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation to all who obey him." (cf. Heb 5:8-9). 1. The text we have just heard in the Lesson for Vespers contains a profound teaching. Once again we realize that God’s word is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword; it penetrates to the depths of the soul and it grants solace and inspiration to his faithful servants (cf. Heb 4:12). I thank God for the opportunity to be with this distinguished Episcopate, which presides over one of the largest Catholic populations in the world. I greet you with a sense of deep communion and sincere affection, well aware of your devotion to the communities entrusted to your care. The warm reception given to me by the Rector of the Catedral da Sé and by all present has made me feel at home in this great common House which is our Holy Mother, the Catholic Church. 2 I extend a special greeting to the new Officers of the National Conference of Brazilian Bishops and, with gratitude for the kind words of its President, Archbishop Geraldo Lyrio Rocha, I offer prayerful good wishes for his work in deepening communion among the Bishops and in promoting common pastoral activity in a territory of continental dimensions. -

Solidarity and Mediation in the French Stream Of

SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Timothy R. Gabrielli Dayton, Ohio December 2014 SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. APPROVED BY: _________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Anthony J. Godzieba, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Timothy R. Gabrielli All rights reserved 2014 iii ABSTRACT SOLIDARITY MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. In its analysis of mystical body of Christ theology in the twentieth century, this dissertation identifies three major streams of mystical body theology operative in the early part of the century: the Roman, the German-Romantic, and the French-Social- Liturgical. Delineating these three streams of mystical body theology sheds light on the diversity of scholarly positions concerning the heritage of mystical body theology, on its mid twentieth-century recession, as well as on Pope Pius XII’s 1943 encyclical, Mystici Corporis Christi, which enshrined “mystical body of Christ” in Catholic magisterial teaching. Further, it links the work of Virgil Michel and Louis-Marie Chauvet, two scholars remote from each other on several fronts, in the long, winding French stream. -

The Eastern Mission of the Pontifical Commission for Russia, Origins to 1933

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2017 Lux Occidentale: The aE stern Mission of the Pontifical Commission for Russia, Origins to 1933 Michael Anthony Guzik University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Guzik, Michael Anthony, "Lux Occidentale: The Eastern Mission of the Pontifical ommiC ssion for Russia, Origins to 1933" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1632. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1632 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LUX OCCIDENTALE: THE EASTERN MISSION OF THE PONTIFICAL COMMISSION FOR RUSSIA, ORIGINS TO 1933 by Michael A. Guzik A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2017 ABSTRACT LUX OCCIDENTALE: THE EASTERN MISSION OF THE PONTIFICAL COMMISSION FOR RUSSIA, ORIGINS TO 1933 by Michael A. Guzik The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2017 Under the Supervision of Professor Neal Pease Although it was first a sub-commission within the Congregation for the Eastern Churches (CEO), the Pontifical Commission for Russia (PCpR) emerged as an independent commission under the presidency of the noted Vatican Russian expert, Michel d’Herbigny, S.J. in 1925, and remained so until 1933 when it was re-integrated into CEO. -

2013 Bibliography Gloria Falcão Dodd University of Dayton, [email protected]

University of Dayton eCommons Marian Bibliographies Research and Resources 2013 2013 Bibliography Gloria Falcão Dodd University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_bibliographies eCommons Citation Dodd, Gloria Falcão, "2013 Bibliography" (2013). Marian Bibliographies. Paper 3. http://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_bibliographies/3 This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Research and Resources at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Bibliographies by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bibliography 2013 Arabic Devotion Lūriyūl.; Yūsuf Jirjis Abū Sulaymān Mutaynī. al-Kawkab al-shāriq fī Maryam Sulṭānat al-Mashāriq : yashtamilu ʻalá sīrat Maryam al-ʻAdhrāʼ wa-manāqibihā wa-ʻibādatihā wa-yaḥtawī namūdhajāt taqwiyah min tārīkh al-Sharq wa-yunāsibu istiʻmāl hādhā al-kitāb fī al-shahr al-Maryamī. Bayrūt: al-Maṭbaʻah al-Kāthūlīkīyah, 1902. Ebook. Music Jenkins, Karl. UWG Concert Choir and Carroll Symphony Orchestra performing Stabat Mater by Karl Jenkins. Carrollton, Georgia: University of West Georgia, 2012. Cd. Aramaic Music Jenkins, Karl. UWG Concert Choir and Carroll Symphony Orchestra performing Stabat Mater by Karl Jenkins. Carrollton, Georgia: University of West Georgia, 2012. Cd. Catalan Music Llibre Vermell: The Red Book of Montserrat. Classical music library. With Winsome Evans and Renaissance Players. [S.l.]: Celestial Harmonies, 2011. eMusic. Chinese Theology Tian, Chunbo. Sheng mu xue. Tian zhu jiao si xiang yan jiu., Shen xue xi lie. Xianggang: Yuan dao chu ban you xian gong si, 2013. English Apparitions Belli, Mériam N. Incurable Past: Nasser's Egypt Then and Now.