Identity and Christ: the Ecclesiological and Soteriological

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Call for Papers LUTHERANISM & the CLASSICS VI: Beauty Concordia Theological Seminary, Fort Wayne, Indiana October 1-2, 2020

Call for Papers LUTHERANISM & THE CLASSICS VI: Beauty Concordia Theological Seminary, Fort Wayne, Indiana October 1-2, 2020 WHAT: From the Reformation onward, Lutherans have not only held the languages and literatures of the ancient Greeks and Romans in high regard, but also respected their theories of aesthetics and artistic sensibilities. While Martin Luther came to believe that beauty is found not in an Aristotelian golden mean but rather in God’s own self- giving in Christ Jesus under forms that may seem ugly to unbelief, he valued proportionality, aesthetics, music, and the visual arts as precious gifts of a generous Creator. Imaging is not only what the human heart does—whether concocting idols or honoring God—but also how the proclaimed word portrays Christ: primarily as divine gift. The conference organizers seek individual papers (or panels with at least three participants) on such topics as follow: Reformation-era Perspectives on Beauty in Plato and Aristotle Lucas Cranach and the Classical Artistic Tradition The Basilica and Church Architecture The Role of Images in the Early Church Beauty and Aesthetics as Understood by the Church Fathers Iconolatry and Iconoclasm The Strange Beauty of the Cross Luther’s Understanding of Beauty under its Apparent Opposite in Selected Psalms Luther on the Theology and Beauty of Music Lutheran Phil-Hellenism Beauty in Orthodoxy, Pietism, and Rationalism Baroque Beauty: Bach and Others Classical Rhetoric and Christian Preaching The Beauty of Holiness Luther’s Aesthetics in Contrast to Modern Views of Beauty How Might Christian Children Learn Aesthetics? Our subject is broadly conceived and considerable latitude will be given to cogent abstracts. -

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa was consecrated as the Roman Catholic Diocesan Bishop of Botucatu in Brazil on December !" #$%&" until certain views he expressed about the treatment of the Brazil’s poor, by both the civil (overnment and the Roman Catholic Church in Brazil caused his removal from the Diocese of Botucatu. His Excellency was subsequently named as punishment as *itular bishop of Maurensi by the late Pope Pius +, of the Roman Catholic Church in #$-.. His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord Carlos Duarte Costa had been a strong advocate in the #$-0s for the reform of the Roman Catholic Church" he challenged many of the 1ey issues such as • Divorce" • challenged mandatory celibacy for the clergy, and publicly stated his contempt re(arding. 2*his is not a theological point" but a disciplinary one 3 Even at this moment in time in an interview with 4ermany's Die 6eit magazine the current Bishop of Rome" Pope Francis is considering allowing married priests as was in the old time including lets not forget married bishops and we could quote many Bishops" Cardinals and Popes over the centurys prior to 8atican ,, who was married. • abuses of papal power, including the concept of Papal ,nfallibility, which the bishop considered a mis(uided and false dogma. His Excellency President 4et9lio Dornelles 8argas as1ed the Holy :ee of Rome for the removal of His Excellency Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa from the Diocese of Botucatu. *he 8atican could not do this directly. 1 | P a g e *herefore the Apostolic Nuncio to Brazil entered into an agreement with the :ecretary of the Diocese of Botucatu to obtain the resi(nation of His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord. -

©® 2002 Joe Griffin 02-10-13-A.CC02-42

©Ê 2002 Joe Griffin 02-10-13-A.CC02-42 / 1 Clanking Chains: Self-Righteous Arrogance: Unhappiness, Iconoclastic, Client Nation, 2 Peter 1:1-2 5) The Arrogance of Unhappiness. We have seen this expression of arrogance associated with Authority Arrogance. The unhappy person is also self-righteous and is preoccupied with self. If he finds himself in a circumstance that causes him to be fearful or angry or both, he has an intense desire to be free of these things. Fascism and Nazism caused the founders of the Frankfurt School to first be afraid and then to become angry. They were unable to evaluate the historical circumstances surrounding the Third Reich from establishment viewpoint let alone biblical viewpoint. Unable to analyze these historical events as the ultimate act of fallen men driven by self- righteous arrogance, they chose instead to analyze them from the viewpoint of the West’s corrupt culture and authoritarian traditions with Christian theology being one of the major contributors. Fearful of a future repeat performance of fascism, the Frankfurt philosophers switched over to anger in their search for a solution. Implacability is locked-in anger that leads to bitterness. Bitterness is an expression of self-pity which expresses frustration that they can find no solution to their unhappy circumstance. Frustrated, self-righteous people never see their own faults but only the faults of others. These perceived faults may be real or imagined. And the Frankfurt fellows imagined that the causes of their frustrations were Western culture and Christian theology. This entangled them in: 6) Iconoclastic Arrogance. -

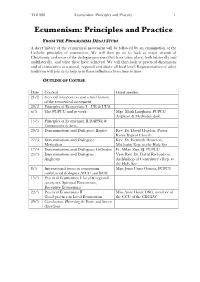

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

Nondualism and the Divine Domain Burton Daniels

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 3 1-1-2005 Nondualism and the Divine Domain Burton Daniels Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Daniels, B. (2005). Daniels, B. (2005). Nondualism and the divine domain. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 24(1), 1–15.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 24 (1). http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2005.24.1.1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nondualism and the Divine Domain Burton Daniels This paper claims that the ultimate issue confronting transpersonal theory is that of nondual- ism. The revelation of this spiritual reality has a long history in the spiritual traditions, which has been perhaps most prolifically advocated by Ken Wilber (1995, 2000a), and fully explicat- ed by David Loy (1998). Nonetheless, these scholarly accounts of nondual reality, and the spir- itual traditions upon which they are based, either do not include or else misrepresent the reve- lation of a contemporary spiritual master crucial to the understanding of nondualism. Avatar Adi Da not only offers a greater differentiation of nondual reality than can be found in contem- porary scholarly texts, but also a dimension of nondualism not found in any previous spiritual revelation. -

Islam and Christian Theologians

• CTSA PROCEEDINGS 48 (1993): 41-54 • ISLAM AND CHRISTIAN THEOLOGIANS Once upon a time an itinerant grammarian came to a body of water and enlisted the services of a boatman to ferry him across. As they made their way, the grammarian asked the boatman, "Do you know the science of grammar?" The humble boatman thought for a moment and admitted somewhat dejectedly that he did not. Not much later, a growing storm began to imperil the small vessel. Said the boatman to the grammarian, "Do you know the science of swimming?" On the eve of the new millennium too much of our theological activity remains shockingly intramural. Instead of allowing an inherent energy to launch us into the larger reality of global religiosity, we insist on protecting our theology from the threat of contamination. If we continue to resist serious engagement with other theological traditions, and that of Islam in particular, our theology may prove as useful as grammar in a typhoon. But what would swimming look like in theological terms? In the words of Robert Neville, "One of the most important tasks of theology today is to develop strategies for determining how to enter into the meaning system of another tradition, not merely as a temporary member of that tradition, but in such a way as to see how they bear upon one another."1 I propose to approach this vast subject by describing the "Three M's" of Muslim-Christian theological engagement: Models (or methods from the past); Method (or a model for future experimentation); and Motives. I. -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC JOURNEY OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI TO BRAZIL ON THE OCCASION OF THE FIFTH GENERAL CONFERENCE OF THE BISHOPS OF LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN MEETING AND CELEBRATION OF VESPERS WITH THE BISHOPS OF BRAZIL ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI Catedral da Sé, São Paulo Friday, 11 May 2007 Dear Brother Bishops! "Although he was the Son of God, he learned obedience through what he suffered; and being made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation to all who obey him." (cf. Heb 5:8-9). 1. The text we have just heard in the Lesson for Vespers contains a profound teaching. Once again we realize that God’s word is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword; it penetrates to the depths of the soul and it grants solace and inspiration to his faithful servants (cf. Heb 4:12). I thank God for the opportunity to be with this distinguished Episcopate, which presides over one of the largest Catholic populations in the world. I greet you with a sense of deep communion and sincere affection, well aware of your devotion to the communities entrusted to your care. The warm reception given to me by the Rector of the Catedral da Sé and by all present has made me feel at home in this great common House which is our Holy Mother, the Catholic Church. 2 I extend a special greeting to the new Officers of the National Conference of Brazilian Bishops and, with gratitude for the kind words of its President, Archbishop Geraldo Lyrio Rocha, I offer prayerful good wishes for his work in deepening communion among the Bishops and in promoting common pastoral activity in a territory of continental dimensions. -

Paganism and Idolatry in Near Eastern Christianity

Durham E-Theses 'The Gods of the Nations are Idols' (Ps. 96:5): Paganism and Idolatry in Near Eastern Christianity NICHOLS, SEBASTIAN,TOBY How to cite: NICHOLS, SEBASTIAN,TOBY (2014) 'The Gods of the Nations are Idols' (Ps. 96:5): Paganism and Idolatry in Near Eastern Christianity, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10616/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Sebastian Toby Nichols ‘The Gods of the Nations are Idols’ (Ps. 96:5): Paganism and Idolatry in Near Eastern Christianity This thesis will explore the presentation in Christian literature of gentile religious life in the Roman Near East in the first few centuries AD. It will do so by performing a close study of three sources – the Syriac Oration of Meliton the Philosopher, the Syriac translation of the Apology of Aristides, and the Greek Address to the Greeks of Tatian. -

Creationism Or Evolution

I CONVERSATIONS WITH CHARLES Creationism* or evolution: is there a valid distinction? Pressure to impose extreme philosophies seems to be I tried a different tack. ‘Many scientists argue that Clin Med increasing throughout the world, including in the so- the mechanisms that they observe, for example 2006;6:629–30 called liberal democracies. I raised one example with evolution, are so beautiful that they are sufficient in Charles and he likened it to another form of themselves to negate the need for a god.’ extremism that I had hardly recognised as such. ‘Is that not pantheism? This holds that creation ‘Charles, do you not think that those in America and creator are one and the same, which is in effect who advocate teaching creationism in primary their position: a position that many of them appear schools are arrogant in the extreme?’ to find emotionally as well as intellectually satisfying. Further, most monotheistic approaches ‘Yes, if the approach is absolute,’ he replied, adding, have a pantheistic element in suggesting that we see ‘but no more so than those who advocate the God in his creation and its beauty. So the two views teaching of absolute Darwinism in this country! may not be as different as the protagonists might One is fundamentalist Christianity and the other wish. Both accept the concept of beauty which fundamentalist pantheism, much as the surely is metaphysical!’ protagonists might not recognise or like the label.’ I turned to the creationists. ‘What are the major ‘But surely the first requires imposing one’s faith on problems for the other side?’ others and the second does not?’ ‘How does God who is outside this world intervene?’ ‘The difference is less than you suggest, Coe! If knowledge implies proof and belief acceptance of ‘Heaven only knows!’ the unprovable then the fundamentalists in both camps are depending on belief, or faith, and not on ‘An appropriate response, Coe! But, once again, just knowledge.’ because you cannot conceive how it happens, it does not mean it does not happen. -

Solidarity and Mediation in the French Stream Of

SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Timothy R. Gabrielli Dayton, Ohio December 2014 SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. APPROVED BY: _________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Anthony J. Godzieba, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Timothy R. Gabrielli All rights reserved 2014 iii ABSTRACT SOLIDARITY MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. In its analysis of mystical body of Christ theology in the twentieth century, this dissertation identifies three major streams of mystical body theology operative in the early part of the century: the Roman, the German-Romantic, and the French-Social- Liturgical. Delineating these three streams of mystical body theology sheds light on the diversity of scholarly positions concerning the heritage of mystical body theology, on its mid twentieth-century recession, as well as on Pope Pius XII’s 1943 encyclical, Mystici Corporis Christi, which enshrined “mystical body of Christ” in Catholic magisterial teaching. Further, it links the work of Virgil Michel and Louis-Marie Chauvet, two scholars remote from each other on several fronts, in the long, winding French stream. -

Is "Nontheist Quakerism" a Contradiction of Terms?

Quaker Religious Thought Volume 118 Article 2 1-1-2012 Is "Nontheist Quakerism" a Contradiction of Terms? Paul Anderson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/qrt Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Paul (2012) "Is "Nontheist Quakerism" a Contradiction of Terms?," Quaker Religious Thought: Vol. 118 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/qrt/vol118/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quaker Religious Thought by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IS “NONTHEIST QUAKERISM” A CONTRADICTION OF TERMS? Paul anderson s the term “Nontheist Friends” a contradiction of terms? On one Ihand, Friends have been free-thinking and open theologically, so liberal Friends have tended to welcome almost any nonconventional trend among their members. As a result, atheists and nontheists have felt a welcome among them, and some Friends in Britain and Friends General Conference have recently explored alternatives to theism. On the other hand, what does it mean to be a “Quaker”—even among liberal Friends? Can an atheist claim with integrity to be a “birthright Friend” if one has abandoned faith in the God, when the historic heart and soul of the Quaker movement has diminished all else in service to a dynamic relationship with the Living God? And, can a true nontheist claim to be a “convinced Friend” if one declares being unconvinced of God’s truth? On the surface it appears that one cannot have it both ways. -

God Is Not a Person (An Argument Via Pantheism)

International Journal for Philosophy of Religion (2019) 85:281–296 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11153-018-9678-x ARTICLE God is not a person (an argument via pantheism) Simon Hewitt1 Received: 22 November 2017 / Accepted: 3 July 2018 / Published online: 6 July 2018 © The Author(s) 2018 Abstract This paper transforms a development of an argument against pantheism into an objection to the usual account of God within contemporary analytic philosophy (’Swinburnian theism’). A standard criticism of pantheism has it that pantheists cannot ofer a satisfactory account of God as personal. My paper will develop this criticism along two lines: frst, that personhood requires contentful mental states, which in turn necessitate the membership of a linguistic community, and second that personhood requires limitation within a wider context constitutive of the ’setting’ of the agent’s life. Pantheism can, I argue, satisfy neither criterion of personhood. At this point the tables are turned on the Swinburnian theist. If the pantheist cannot defend herself against the personhood-based attacks, neither can the Swinburnian, and for instructively parallel reasons: for neither doctrine is God in the material world; in the pantheist case God is identical with the world, in the Swinburnian case God transcends it. Either way both the pantheist and the Swinburnian are left with a dilemma: abandon divine personhood or modify the doctrine of God so as to block the move to personhood. Keywords Pantheism · Divine personhood · Apophaticism · Divine language Is God a person? Since the advent of philosophy of religion in the analytic tradi- tion the consensus of opinion has favoured answering this question in the afrma- tive (as we will see in due course).