Chapter 7 the Presidency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations Updated July 6, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46236 SUMMARY R46236 Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations July 6, 2020 Occupying almost half of South America, Brazil is the fifth-largest and fifth-most-populous country in the world. Given its size and tremendous natural resources, Brazil has long had the Peter J. Meyer potential to become a world power and periodically has been the focal point of U.S. policy in Specialist in Latin Latin America. Brazil’s rise to prominence has been hindered, however, by uneven economic American Affairs performance and political instability. After a period of strong economic growth and increased international influence during the first decade of the 21st century, Brazil has struggled with a series of domestic crises in recent years. Since 2014, the country has experienced a deep recession, record-high homicide rate, and massive corruption scandal. Those combined crises contributed to the controversial impeachment and removal from office of President Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016). They also discredited much of Brazil’s political class, paving the way for right-wing populist Jair Bolsonaro to win the presidency in October 2018. Since taking office in January 2019, President Jair Bolsonaro has begun to implement economic and regulatory reforms favored by international investors and Brazilian businesses and has proposed hard-line security policies intended to reduce crime and violence. Rather than building a broad-based coalition to advance his agenda, however, Bolsonaro has sought to keep the electorate polarized and his political base mobilized by taking socially conservative stands on cultural issues and verbally attacking perceived enemies, such as the press, nongovernmental organizations, and other branches of government. -

The Role of Parliaments in the Semi-Presidential Systems: the Case of the Federal Assembly of Russia a Thesis Submitted to Th

THE ROLE OF PARLIAMENTS IN THE SEMI-PRESIDENTIAL SYSTEMS: THE CASE OF THE FEDERAL ASSEMBLY OF RUSSIA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY RABĠA ARABACI KARĠMAN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF EURASIAN STUDIES OCTOBER 2019 DEDICATIONTASLAK I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Rabia Arabacı Kariman Signature : iii ABSTRACT THE ROLE OF PARLIAMENTS IN THE SEMI-PRESIDENTIAL SYSTEMS: THE CASE OF THE FEDERAL ASSEMBLY OF RUSSIA Arabacı Kariman, Rabia M.Sc., Department of Eurasian Studies Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. IĢık KuĢçu Bonnenfant October 2019, 196 pages The purpose of this thesis is to scrutinize the role and status of the Federal Assembly of Russia within the context of theTASLAK semi-presidential system in the Russian Federation. Parliaments as a body incorporating the representative and legislative functions of the state are of critical importance to the development and stability of democracy in a working constitutional system. Since the legislative power cannot be thought separate from the political system in which it works, semi-presidentialism practices of Russia with its opportunities and deadlocks will be vital to understand the role of parliamentary power in Russia. The analysis of the the relationship among the constitutional bodies as stipulated by the first post-Soviet Constitution in 1993 will contribute to our understanding of the development of democracy in the Russian Federation. -

Digital Tools and the Derailment of Iceland's New Constitution

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Gylfason, Thorvaldur; Meuwese, Anne Working Paper Digital Tools and the Derailment of Iceland's New Constitution CESifo Working Paper, No. 5997 Provided in Cooperation with: Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Suggested Citation: Gylfason, Thorvaldur; Meuwese, Anne (2016) : Digital Tools and the Derailment of Iceland's New Constitution, CESifo Working Paper, No. 5997, Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/145032 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Digital Tools and the Derailment of Iceland’s New Constitution Thorvaldur Gylfason Anne Meuwese CESIFO WORKING PAPER NO. -

Presidential Or Parliamentary Does It Make a Difference? Juan J. Linz

VrA Democracy: Presidential or Parliamentary Does it Make a Difference? Juan J. Linz Pelatiah Pert Professor of Political and Social Sciences Yale University July 1985 Paper prepared for the project, "The Role of Political Parties in the Return to Democracy in the Southern Cone," sponsored by the Latin American Program of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and the World Peace Foundation Copyright © 1985 by Juan J. Linz / INTRODUCTION In recent decades renewed efforts have been made to study and understand the variety of political democracies, but most of those analyses have focused on the patterns of political conflict and more specifically on party systems and coalition formation, in contrast to the attention of many classical writers on the institutional arrangements. With the exception of the large literature on the impact of electorul systems on the shaping of party systems generated by the early writings of Ferdinand Hermens and the classic work by Maurice Duverger, as well as the writings of Douglas Rae and Giovanni Sartori, there has been little attention paid by political scientists to the role of political institutions except in the study of particular countries. Debates about monarchy and republic, parliamentary and presidential regimes, the unitary state and federalism have receded into oblivion and not entered the current debates about the functioning of democra-ic and political institutions and practices, including their effect on the party systems. At a time when a number of countries initiate the process of writing or rewriting constitu tions, some of those issues should regain salience and become part of what Sartori has called "political engineering" in an effort to set the basis of democratic consolidation and stability. -

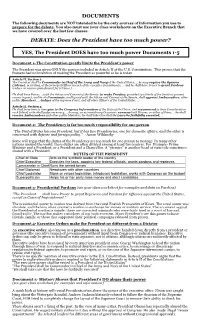

DOCUMENTS DEBATE: Does the President Have Too Much Power?

DOCUMENTS The following documents are NOT intended to be the only sources of information you use to prepare for the debate. You also must use your class worksheets on the Executive Branch that we have covered over the last few classes. DEBATE: Does the President have too much power? YES, The President DOES have too much power Documents 1-5 Document 1- The Constitution greatly limits the President’s power The President was given ONLY the powers included in Article II of the U.S. Constitution. This proves that the framers had no intention of making the President as powerful as he is today. Article II, Section 2 The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, … he may require the Opinion (Advice), in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, … and he shall have Power to grant Pardons (reduce or remove punishment) for [Crimes,] …. He shall have Power, …with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur (agree); and he shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers …, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, …: Article II, Section 3 He shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such [ideas] as he shall judge necessary…; he may, on extraordinary Occasions, convene both Houses, or either of them, … he shall receive Ambassadors and other public Ministers; he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed, …. -

Types of Semi-Presidentialism and Party Competition Structures in Democracies: the Cases of Portugal and Peru Gerson Francisco J

TYPES OF SEMI-PRESIDENTIALISM AND PARTY COMPETITION STRUCTURES IN DEMOCRACIES: THE CASES OF PORTUGAL AND PERU GERSON FRANCISCO JULCARIMA ALVAREZ Licentiate in Sociology, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (Peru), 2005. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in POLITICAL SCIENCE Department of Political Science University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Gerson F. Julcarima Alvarez, 2020 TYPES OF SEMI-PRESIDENTIALISM AND PARTY COMPETITION STRUCTURES IN DEMOCRACIES: THE CASES OF PORTUGAL AND PERU GERSON FRANCISCO JULCARIMA ALVAREZ Date of Defence: November 16, 2020 Dr. A. Siaroff Professor Ph.D. Thesis Supervisor Dr. H. Jansen Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. J. von Heyking Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. Y. Belanger Professor Ph.D. Chair, Thesis Examination Committee ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes the influence that the semi-presidential form of government has on the degree of closure of party competition structures. Thus, using part of the axioms of the so-called Neo-Madisonian theory of party behavior and Mair's theoretical approach to party systems, the behavior of parties in government in Portugal (1976-2019) and Peru (1980-1991 and 2001-2019) is analyzed. The working hypotheses propose that the president-parliamentary form of government promotes a decrease in the degree of closure of party competition structures, whereas the premier- presidential form of government promotes either an increase or a decrease in the closure levels of said structures. The investigation results corroborate that apart from the system of government, the degree of closure depends on the combined effect of the following factors: whether the president's party controls Parliament, the concurrence or not of presidential and legislative elections, and whether the party competition is bipolar or multipolar. -

Australia's System of Government

61 Australia’s system of government Australia is a federation, a constitutional monarchy and a parliamentary democracy. This means that Australia: Has a Queen, who resides in the United Kingdom and is represented in Australia by a Governor-General. Is governed by a ministry headed by the Prime Minister. Has a two-chamber Commonwealth Parliament to make laws. A government, led by the Prime Minister, which must have a majority of seats in the House of Representatives. Has eight State and Territory Parliaments. This model of government is often referred to as the Westminster System, because it derives from the United Kingdom parliament at Westminster. A Federation of States Australia is a federation of six states, each of which was until 1901 a separate British colony. The states – New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania - each have their own governments, which in most respects are very similar to those of the federal government. Each state has a Governor, with a Premier as head of government. Each state also has a two-chambered Parliament, except Queensland which has had only one chamber since 1921. There are also two self-governing territories: the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory. The federal government has no power to override the decisions of state governments except in accordance with the federal Constitution, but it can and does exercise that power over territories. A Constitutional Monarchy Australia is an independent nation, but it shares a monarchy with the United Kingdom and many other countries, including Canada and New Zealand. The Queen is the head of the Commonwealth of Australia, but with her powers delegated to the Governor-General by the Constitution. -

On the Commander-In-Chief Power

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2008 On the Commander-In-Chief Power David Luban Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 1026302 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/598 http://ssrn.com/abstract=1026302 81 S. Cal. L. Rev. 477-571 (2008) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons ON THE COMMANDER IN CHIEF POWER ∗ DAVID LUBAN BRADBURY: Obviously, the Hamdan decision, Senator, does implicitly recognize that we’re in a war, that the President’s war powers were triggered by the attacks on the country, and that [the] law of war paradigm applies. That’s what the whole case was about. LEAHY: Was the President right or was he wrong? BRADBURY: It’s under the law of war that we . LEAHY: Was the President right or was he wrong? BRADBURY: . hold the President is always right, Senator. —exchange between a U.S. Senator and a Justice Department 1 lawyer ∗ University Professor and Professor of Law and Philosophy, Georgetown University. I owe thanks to John Partridge and Sebastian Kaplan-Sears for excellent research assistance; to Greg Reichberg, Bill Mengel, and Tim Sellers for clarifying several points of American, Roman, and military history; to Marty Lederman for innumerable helpful and critical conversations; and to Vicki Jackson, Paul Kahn, Larry Solum, and Amy Sepinwall for helpful comments on an earlier draft. -

Establishing a Lebanese Senate: Bicameralism and the Third Republic

CDDRL Number 125 August 2012 WORKING PAPERS Establishing a Lebanese Senate: Bicameralism and the Third Republic Elias I. Muhanna Brown University Center on Democracy, Development, and The Rule of Law Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Additional working papers appear on CDDRL’s website: http://cddrl.stanford.edu. Working Paper of the Program on Arab Reform and Democracy at CDDRL. About the Program on Arab Reform and Democracy: The Program on Arab Reform and Democracy examines the different social and political dynamics within Arab countries and the evolution of their political systems, focusing on the prospects, conditions, and possible pathways for political reform in the region. This multidisciplinary program brings together both scholars and practitioners - from the policy making, civil society, NGO (non-government organization), media, and political communities - as well as other actors of diverse backgrounds from the Arab world, to consider how democratization and more responsive and accountable governance might be achieved, as a general challenge for the region and within specific Arab countries. The program aims to be a hub for intellectual capital about issues related to good governance and political reform in the Arab world and allowing diverse opinions and voices to be heard. It benefits from the rich input of the academic community at Stanford, from faculty to researchers to graduate students, as well as its partners in the Arab world and Europe. Visit our website: arabreform.stanford.edu Center on Democracy, Development, and The Rule of Law Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Stanford University Encina Hall Stanford, CA 94305 Phone: 650-724-7197 Fax: 650-724-2996 http://cddrl.stanford.edu/ About the Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law (CDDRL) CDDRL was founded by a generous grant from the Bill and Flora Hewlett Foundation in October in 2002 as part of the Stanford Institute for International Studies at Stanford University. -

1 Should the Governor General Be Canada's Head of State?

Should the Governor General be Canada’s Head of State? CES Franks Remarks prepared for the Annual Meeting of the Canadian Study of Parliament Group Ottawa, 26 March 2010. Revised 30 March 2010 In a speech in Paris to UNESCO on 5 October 2009, Canada’s Governor General, Michaëlle Jean, said that: “I, a francophone from the Americas, born in Haiti, who carries in her the history of the slave trade and the emancipation of blacks, at once Québécoise and Canadian, and today before you, Canada's head of state, proudly represents the promises and possibilities of that ideal of society." This seemingly innocuous statement, which it might be thought would have made Canadians proud that their country could be so open, free, and ready to accept and respect able persons regardless of sex, colour, creed, or origins, instead became a matter of controversy and debate. The issue was Mme. Jean’s use of the term “head of state” to describe her position. Former Governor General Adrienne Clarkson had referred to herself as head of state without creating any controversy. Now it was controversial. Prime Minister Harper himself joined in the fray, as did the Monarchist League of Canada, both stating categorically that Queen Elizabeth II of England was Canada’s head of state, while the position of Governor General was as the Queen’s representative in Canada. At the time, the Governor General’s website included several statements such as: “As representative of the Crown and head of State, the Governor General carries out responsibilities with a view to promoting Canadian sovereignty and representing Canada abroad and at home." Within a few weeks these references had been deleted on the insistence of the government. -

Europe: Fact Sheet on Parliamentary and Presidential Elections

Europe: Fact Sheet on Parliamentary and Presidential Elections July 30, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46858 Europe: Fact Sheet on Parliamentary and Presidential Elections Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 European Elections in 2021 ............................................................................................................. 2 European Parliamentary and Presidential Elections ........................................................................ 3 Figures Figure 1. European Elections Scheduled for 2021 .......................................................................... 3 Tables Table 1. European Parliamentary and Presidential Elections .......................................................... 3 Contacts Author Information .......................................................................................................................... 6 Europe: Fact Sheet on Parliamentary and Presidential Elections Introduction This report provides a map of parliamentary and presidential elections that have been held or are scheduled to hold at the national level in Europe in 2021, and a table of recent and upcoming parliamentary and presidential elections at the national level in Europe. It includes dates for direct elections only, and excludes indirect elections.1 Europe is defined in this product as the fifty countries under the portfolio of the U.S. Department -

Cabinet and Presidency - Kozo Kato

GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS – Vol. I - Cabinet and Presidency - Kozo Kato CABINET AND PRESIDENCY Kozo Kato Sophia University, Japan Keywords: Cabinet, Coalition government, Judicial review, Leadership, Parliament, Political executives, Presidency, Vote of non-confidence. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Conventional Typology of Political Executives 2.1 Cabinet 2.2 Presidency 3. Varieties of Cabinet and Presidency 4. Transitional Democracies 5. Governmental System, Leadership, and Performance Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary Cabinet and presidency represent the two most important and prevalent types of political executive. The structures and functions of political executives have varied widely over time and place, and no single conceptual framework can contain all these variations and their consequences. Although this section is titled “Cabinet and Presidency,” it is often difficult to categorize existing political executives as belonging to one or the other of the two types. Therefore, when we discuss ideal types of cabinet and presidential government, conceptual confusion should be carefully avoided between the form of government (the power structure of separation and sharing) and the performance of the government (the efficacy of strong and weak leadership). 1. Introduction Cabinet and presidency represent the two most important and prevalent types of political UNESCOexecutive. Most children are politically – EOLSS socialized through their perceptions of top political executives, and those positions have been the locus of post-war world politics, as demonstratedSAMPLE in strong leadership CHAPTERS of such men and women as Adenauer, Churchill, Deng Xiaoping, Gandhi, de Gaulle, Gorbachev, Reagan, and Roosevelt. However, political scientists have often neglected the structures and functions of such governmental institutions and concentrated on societal phenomena such as pressure groups, party politics, public opinion, and elections.